Germany After Unification: Views from Abroad ROGER HILLMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Surreal Without Surrealism

INTRODUCTION The Surreal without Surrealism The time will come, if it is not already come, when the surrealist enterprise:': will be studied and evaluated, in the history of literature, as an adventure of hope. —Wallace Fowlie, Age of Surrealism Indubitably, Surrealism and the GDR are closely connected, and are more closely related to each other than one might think. When, for example, one listens to the recollections and reads the memoirs of those who lived in this country, apparently no other conclusion can be drawn. Life in the East German Communist state had a surrealistic disposition, was associated with the grotesque, absurd and irrational. Admittedly, Surrealism did not exist in the GDR. Not only are the insights of Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Peter Bürger on the death of the historical avant-garde convincing and applicable to the GDR;1 it is also significant that no German artist or writer who considered him- or herself a Surrealist prior to 1945 returned from exile to settle in the SBZ or the GDR. Most of the celebrities of German Surrealism during the Weimar Republic were forced to go into exile or did not return to Germany at all. Max Ernst, for example, remained living in the USA, and then in 1953 moved to his wife’s old quarters in Paris; Hans Arp decided to live in Switzerland, and in 1949 chose the USA as his home country. Others who had lived through and survived Hitler’s Germany had to face the harsh demands of National Socialist cultural politics that downgraded the avant-garde to the status of Entartete Kunst, or degenerate art, and sidelined and even terrorized its representatives. -

Objectification As a Device in the Films of Godard and Breillat: Alphaville (1965) And

Objectification as a Device in the Films of Godard and Breillat: Alphaville (1965) and Romance (1999) A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction in the Department of French and Italian in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Zachary Gooch The Ohio State University November 2005 Project Advisor: Professor Judith Mayne, Department of French and Italian Gooch 2 “In order to live in a society in Paris today, on no matter what level, one is forced to prostitute oneself in one way or another—or to put it another way, to live under conditions resembling those of prostitution […] in a modern society, prostitution is the norm.” – Jean-Luc Godard (Le Nouvel Observateur 1966) “It seems to me that in Paris today, we are all living more or less in a state of prostitution. The increase in prostitution, literally speaking, is partial proof of this statement because it calls into question the body, but one can prostitute oneself just as equally with the mind, the spirit. I think it is a collective phenomenon, and perhaps one which is not altogether new. But what is new is that people find it normal.” – Godard (qtd. in Roud 34) Film criticism’s grasp is often limited by the enumeration of the characteristics of a director’s work, which wrongfully implies that each characteristic is a fairly autonomous and separate concern. One of the oft cited preoccupations in Godard’s cinema is prostitution as a social metaphor. However, his use of prostitution as a trope for the state of existence in modern society is closely related to another of these supposedly separate concerns: language. -

CHEYNEY, Peter Geboren Als Reginald "Reg" Evelyn Peter Southouse-Cheyney Geboren: Whitechapel, Londen, 22 Februari 1896

CHEYNEY, Peter Geboren als Reginald "Reg" Evelyn Peter Southouse-Cheyney Geboren: Whitechapel, Londen, 22 februari 1896. Overleden: 26 juni 1951 Pseudoniem: Harold Brust Opleiding: advokaat. Carrière: werkte als songwriter, bookmaker, journalist en politicus Militaire dienst: luitenant, British Army; vrijwiller semi-officiële Organisation of the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS). Familie: drie keer getrouwd geweest, o.a. met een danseres (foto: Goodreads.com) website met boekomslagen: http://www.petercheyney.co.uk/Cheyney%20Site/bookshollandcovers.html detective: Lemmuel H. ‘ Lemmy’ Caution , G-man van de F.B.I., cynisch en gewelddadig; Slim Callaghan , privé-detective, Londen; Nick Bellamy , privé-detective; Johnny Vallon , privé-detective, Londen; Michael Kells ; Everard Peter Quayle , spion (" Dark"-serie ), van een top-geheime Britse contra-spionage eenheid, die opereert tegen Nazi-agenten in het Engeland van de Tweede Wereld Oorlog detective: Alonzo MacTavish (kv); Abie Hymie Finkelstein (kv); Etienne MacGregor (kv); Julia Herron (kv); Krasinsky (kv) Lemmy Caution : 1. This Man is Dangerous 1936 Miranda is goedkoper dan U denkt 1957 ZB 65 ook verschenen odt: Deze man is gevaarlijk 1985 ZB 65 2. Poison Ivy 1937 Giftige klimop 1958 ZB 166 eerder verschenen odt: Charlotte is gevaarlijk 1939 Schuyt Fol 21 3. Dames Don't Care 1937 Een vrouw ziet nergens tegenop 1949/61 Br/ZB 422 4. Can Ladies Kill? 1938 Zijn vrouwen moordenaars? 1956/86 ZB 11/ZB 22 5. Don't Get Me Wrong! 1939 Begrijp me niet verkeerd! 1961 ZB 421 6. You'd Be Surprised 1940 Daar sta je van te kijken 1958 ZB 142 7. Your Deal, My Lovely 1941 Jouw beurt, jongedame 1949/60 Bruna/ZB 296 8. -

Documenting the Documentary Grant.Indd 522 10/3/13 10:08 AM Borat 523

Chapter 31 Cultural Learnings of Borat for Make Benefit Glorious Study of Documentary Leshu Torchin Genre designations can reflect cultural understandings of boundaries between perception and reality, or more aptly, distinctions between ac- cepted truths and fictions, or even between right and wrong. Borat: Cul- tural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (Larry Charles, 2006) challenges cultural assumptions by challenging our generic assumptions. The continuing struggle to define the film reflected charged territory of categorization, as if locating the genre would secure the meaning and the implications of Borat. Most efforts to categorize it focused on the humor, referring to it as mockumentary and comedy. But such classifications do not account for how Borat Sagdiyev (Sacha Baron Cohen) interacts with people onscreen or for Baron Cohen’s own claims that these encounters produce significant information about the world. Fictional genres always bear some degree of indexical relationship to the lived world (Sobchack), and that relationship only intensifies in a tradi- tional documentary. Borat, however, confuses these genres: a fictional TV host steps out of the mock travelogue on his fictional hometown and steps into a journey through a real America. The indexical relationship between the screen world and the real world varies, then, with almost every scene, sometimes working as fiction, sometimes as documentary, sometimes as mockumentary. In doing so, the film challenges the cultural assumptions that inhere to expectations of genre, playing with the ways the West (for 13500-Documenting the Documentary_Grant.indd 522 10/3/13 10:08 AM Borat 523 lack of a better shorthand) has mapped the world within the ostensibly rational discourses of nonfiction. -

Portrait: Ulrike Ottinger | Photo: Anne Selders 2010

Ulrike Ottinger grew up in the city of Constance on Lake Constance where she set up her own studio at an early age. From 1962 until the beginning of 1969 she worked as an independent artist in Paris, while learning the technique of etching from Johnny Friedlaender. She also attended lectures given by Claude Lévi-Strauss, Louis Althusser and Pierre Bourdieu at the Collège de France. She exhibited her work at the Biennale internationale de l’estampe, Paris and in various galleries. In the early 70s her interest in painting, photography and performance lead her into making films. Her first film script, ‘The Mongolian Double Drawer’ (Die Mongolische Doppelschublade) was written in 1966. After her return to West Germany she founded, in association with Constance University, the ‘filmclub visuell’ in 1969 in Constance in which international Independent Films, the New German Cinema (Neuer Deutscher Film) and historical films were shown. At the same time she set up the gallery and the edition ‘galeriepress’, in which she presented Wolf Vostell, Allan Kaprow, Fernand Teyssier, Peter Klasen and English pop artists such as R. B. Kitaj, Joe Tilson, Richard Hamilton and David Hockney. Her first film, ‘Laocoon and Sons’ (Laokoon und Söhne), made in collaboration with Tabea Blumenschein, was recorded in 1971-1973 and celebrated its world premiere in the Arsenal Berlin. In 1973 she moved to Berlin and filmed the Happening-documentary ‘Berlinfever – Wolf Vastell’ (Berlinfieber – Wolf Vastell). This was followed by ‘The Enchantment of the Blue Sailors’ (Die Betörung der Blauen Matrosen) in 1975 with Valeska Gert and ‘Madame X – An Absolute Ruler’ (Madame X – Eine absolute Herrscherin) in 1977, co-produced by the ZDF, which caused a great sensation and was an international success. -

GDR Literature in the International Book Market: from Confrontation to Assimilation

GDR Bulletin Volume 16 Issue 2 Fall Article 4 1990 GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontation to Assimilation Mark W. Rectanus Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Rectanus, Mark W. (1990) "GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontation to Assimilation," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 16: Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/gdrb.v16i2.961 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Rectanus: GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontati 2 'Gisela Helwig, ed. Die DDR-Gesellschaft im Spiegel ihrer Literatur Günter Grass, Christoph Meckel and Hans Werner Richter). (Köln: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1986); Irma Hanke, Alltag und However, the socio-critical profile of the "Quarthefte" and his Politik, see note 17 above. commitment to leftist politics soon led to new problems: 22Cf. Wolfgang Emmerich, „Gleichzeitigkeit: Vormoderne, Moderne und Postmoderne in der Literatur der DDR" in: Bestandsaufnahme Das erste Jahr brachte dem Verlag aber auch die ersten Gegenwartsliteratur, 193-211; Bernhard Greiner, „Annäherungen: Schwierigkeiten. Die eine bestand im Boykott der konser• DDR-Literatur als Problem der Literaturwissenschaft" in: Mitteilungen vativen Presse (hauptsächlich wegen der Veröffentlichung des deutschen Germanistenverbandes 30 (1983), 20-36; Anneli Hart• von Stephan Hermlin, dessen Bücher bis dahin von west• mann, „Was heißt heute überhaupt noch DDR-Literatur?" in: Studies in deutschen Verlagen boykottiert worden waren, aber auch GDR Culture and Society 5 (1985), 265-280; Heinrich Mohr, „DDR- wegen der Veröffentlichung von Wolf Biermann). -

Good Work, Little Soldier: Text and Pretext

First published in Journal of European Studies 34:1-2 (2004), pp.34-43 Good Work, Little Soldier: text and pretext Adaptation, the most explicit kind of intertextual relation implicating film, is not really intertextual at all, if intertextuality is understood to be a systematic, ongoing and infinite ramification of meanings that command our critical pause. But if we apply a more restricted model from literary theory, centred on a ‘centring text which retains its position of leadership in meaning’,1 adaptation can be read through a variation of this model: pretextuality. Film-on-book relations are generally pretextual: the adapted text as point of departure, as party in a dialogue, as measure of a difference, as mirror. Beau travail has two pretexts, a book and a film: Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor (1891) and Godard’s Le petit soldat (1960). The first is the kind of pretext familiar from cinematic adaptations of literary works, though it is made strange by reference to an intermediate operatic adaptation (Britten’s Billy Budd). The second is of a quite unfamiliar kind, a variant of cinematic pretextuality that may be peculiar to Beau travail. Most comparable instances of character and actor reappearing in a different director’s film would be from sequels or episodes in series,2 but though Michel Subor plays Bruno Forestier in both films, Beau travail is not, in narrative terms, a sequel to Le petit soldat. A more exact idea of the film-on-film relations that bind the two films is the object of this article. ‘Pretext and intertext’ is not a categorical distinction: pretextuality is just over- determined intertextuality. -

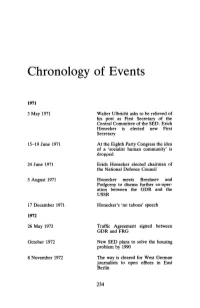

Chronology of Events

Chronology of Events 1971 3 May 1971 Walter Ulbrlcht asks to be relieved of bis post as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED. Erlch Honecker is elected new First Secretary 15-19 June 1971 At the Eighth Party Congress the idea of a 'socialist human community' is dropped 24 June 1971 Erlch Honecker elected chairman of the National Defence Council 5 August 1971 Honecker meets Brezhnev and Podgomy to discuss further co-oper ation between the GDR and the USSR 17 December 1971 Honecker's 'no taboos' speech 1972 26 May 1972 Trafik Agreement signed between GDRandFRG October 1972 New SED plans to solve the housing problem by 1990 8 November 1972 The way is cleared for West German journalists to open offices in East Berlin 234 Chronology 0/ Events 235 21 December 1972 Basic Treaty signed as a first step towards 'normalising' relations between GDR and FRG 1973 21 February 1973 A new regulation against foreign journalists slandering the GDR, its institutions and leading figures 1 August 1973 Walter Ulbricht dies at the age of 80 18 September 1973 East and West Germany are accepted as members of the United Nations 2 October 1973 The Central Committee approves a plan to step up the housing programme 1974 1 February 1974 East German citizens are permitted to possess Western currency 20 June 1974 Günter Gaus becomes the first 'Permanent Representative' of the FRG in the GDR 7 October 1974 Law on the revision of the constitution comes into effect. Concept of one German nation is dropped and doser ties with the Soviet Union stressed 1975 1 August 1975 Helsinki Final Act signed 7 October 1975 Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid between GDR and Soviet Union 16 December 1975 Spiegel reporter Jörg Mettke expelled after another Spiegel reporter publishes a story on compulsory adop tion in the GDR 1976 29-30 June 1976 Conference of 29 Communist and 236 Chronology 0/ Events Workers' Parties in East Berlin. -

The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 43 Number 3 Article 3 11-2007 The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist Axel Fair-Schulz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fair-Schulz, Axel (2007) "The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 43 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol43/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fair-Schulz: The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist by Axel Fair-Schulz Among many East German Marxists, who had embraced Marxism in the 1930s and opted to live in East Germany after World War II (between the 1950s until the end of the GDR in 1989), was a commitment to the Communist party that was informed by a more nuanced and sophisticated Marxism than what most party bureaucrats were exposed to. Among them, for example, the writer Stephan Hermlin as well as the literary scholar Hans Mayer both found their own unique way of accommodating themselves Map showing dividing line to and/or confronting the shortcomings of East between East and West Germany. -

Protest Music, Urban Contexts and Global Perspectives

B. Kutschke: Protest Music, Urban Contexts IRASM 46 (2015) 2: 321-354 and Global Perspectives Beate Kutschke TU Dresden Institut für Kunst- und Musikwissenschaft August-Bebel-Str. 20 01219 Dresden Protest Music, Urban Germany Contexts and Global E-mail: [email protected] UDC: 78.067 Perspectives Original Scholarly Paper Izvorni znanstveni rad Received: February 13, 2015 Primljeno: 13. veljače 2015. Accepted: May 26, 2015 Prihvaćeno: 26. svibnja 2015. Abstract - Résumé This article argues that urban environments in the 1960s and 1970s provided excellent music-cultural and political conditions that stimulated not only protest, but also the crea- I. 1968 – Urbanism and Globalization tion and performance of protest music. It demonstrates this by means of two case studies. The It is evident that urban environments are good music of the Krautrock band CAN in Cologne and the Volks- cradles for protest. Urban environments are marked ambulanz Concert in West by densification and, therefore, offer what protesters Berlin can be considered as emerging from both cities’ and activists need most: the physical presence of unique political and cultural many people – crowds, masses – who express their situations. These were, para- doxically enough, the long-term dissent and forcefully demand change. These densely results of the reorganization of populated urban areas permit the mobilization not Germany after 1945. Both cities possessed lively avant-garde only of protesters, activists, and sympathizers, but music scenes with musicians also journalists and mass media that disseminate the from all over the world, as well as communal grievances that protesters’ message. Furthermore, compact urban triggered protest and protest neighbourhoods compress diverse, heterogeneous music; West Berlin was addi- tionally marked by its specific lifestyles, opinions and value systems opposed to status as a demilitarized zone each other and, thus, catalyze conflicts into protest and immured city. -

Rheingau-Winzer

Fühle deine Stadt. Wiesbaden. Mai 2016 Nr.42 RHEINGAU-WINZER: WIR KÖNNEN AUCH ANDERS FERIEN FÜR ALLE ABGEHÄNGTE KULTUR BIENNALE WEINBAR-TEST EDDIE CONSTANTINE sensor 05/16 3 Editorial / Inhalt Editorial Impressum 5.8.2016 Verlagsgruppe Rhein Main GmbH & Co. KG Kurpark Neue Wege zu gehen, phG: Verlagruppe Rhein Main Verwaltungs- ft gesellschaft mbH Wiesbaden liebe sensor-Leserinnen und Leser, genschaften aufwarten können? Hof- tigt vom riesigen Andrang bei der Geschäftsführer: Hans Georg Schnücker das kann durchaus anstrengender fentlich zumindest ansatzweise, denn 4-Jahre-sensor-Party im Kulturpa- (Sprecher), Dr. Jörn W. Röper sein als auf bewährten, ausgetrete- sie müssen nun neue Wege gehen, last. Vom Aufeinandertreffen ganz Erich Dombrowski Straße 2, 55127 Mainz (zugleich ladungsfähige Anschrift der V.i.S.d.P) nen Pfaden zu bleiben. Es kann sich ob sie wollen oder nicht. Das Wahl- unterschiedlicher großartiger Men- aber auch lohnen. Neue Wege zu ge- ergebnis zwingt sie dazu, ausgetre- schen unserer Stadt, die miteinan- Objektleitung hen, erfordert Mut, Entschlossenheit, tene Pfade zu verlassen. Welches die der ins Gespräch kamen und uns, den (Redaktions- & Anzeigenleitung) Dirk Fellinghauer (Verantwortlich i.S.d.P.) ho Leidenschaft, vielleicht auch eine neuen Wege sein werden und wohin sensor, mit viel Zuspruch sehr glück- Kleine Schwalbacher Str. 7 – 65183 Wiesbaden Portion Verrücktheit. Und in jedem sie führen werden, war am Drucktag lich gemacht haben. Danke vielmals Tel: 0611/355 5268 Fax: 0611/355 5243 Fall einen starken Charakter. All das dieser Ausgabe – vier Tage vor der an alle Beteiligten für diese fantas- www.sensor-wiesbaden.de bringen die Menschen mit, die wir konstituierenden Sitzung der neu ge- tische Nacht! [email protected] für unsere Titelgeschichte aufgesucht wählten Stadtverordnetenversamm- Layout/Satz Thorsten Ullrich, www.175lpi.de haben. -

Management Et Représentation Enquête Sur Les Représentations Du Management Dans Le Cinéma Français, 1895-2005

UNIVERSITE DE NANTES Institut d’Economie et de Management de Nantes – IAE 2008 THESE pour l’obtention du grade de docteur en sciences de gestion présentée et soutenue publiquement par Eve LAMENDOUR le 8 septembre 2008 Management et représentation Enquête sur les représentations du management dans le cinéma français, 1895-2005 Volume 2 : Annexes JURY DIRECTEURS DE RECHERCHE Yannick LEMARCHAND, Professeur à l’Université de Nantes Patrick FRIDENSON, Directeur d'études à l’EHESS RAPPORTEURS Anne PEZET, Professeur à l’Université Paris-Dauphine Pierre SORLIN, Professeur émérite à l’Université Paris III SUFFRAGANTS Mathieu DETCHESSAHAR, Professeur à l’Université de Nantes Hervé LAROCHE, Professeur à l’ESCP-EAP Béatrice de PASTRE, Directrice des collections aux Archives Françaises du Film, CNC ANNEXES Table des annexes 1. Droit d’auteur 3 2. Glossaires 5 a. Glossaire des notions managériales 5 b. Vocabulaire de l’analyse filmique 11 c. Abréviations et termes de référence de la description du corpus 15 3. Filmographies 19 a. Sources d’accès aux films 19 b. Corpus pratique 20 c. Corpus théorique : liste chronologique 35 d. Corpus théorique : fiches des films 43 e. Corpus de comparaison 167 La représentation de l’entreprise et du management dans le cinéma américain 167 Chronologie de films susceptibles d’éclairer la question managériale 168 4. Tableaux 174 a. Chapitre 3 174 Tableau récapitulatif des concessionnaires et agents commerciaux Lumière b. Chapitre 4 175 Sources d’information concernant les films « grévistes » c. Chapitre 10 176 Sources d’information concernant les slogans des cabinets de conseil d. Conclusion Partie IV 177 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, 1936 – 1975 177 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, 1982 – 2000 178 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, les années 2000 179 Evolution des métiers à composante managériale, 1982 – 2006 180 5.