2017 with Joseph Beuys in No Man's Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Begleittexte Joseph Beuys

BEUYS JOSEPH BEUYS Denken. Handeln. Vermitteln. Think. Act. Convey. 4. 3. – 13. 6. 2021 Begleittexte zur Ausstellung Accompanying texts to the exhibition BEUYS UND DIE ÖKOLOGIE Lange bevor Joseph Beuys anlässlich seiner letzten documenta-Teil- nahme 1982 lieber im Stadtraum von Kassel Bäume p anzen als im Museumsgebäude Kunstwerke im herkömmlichen Sinn präsentieren wollte, interessierte sich der Künstler für den Gesamtzusammenhang aller Lebensformen. So fand er etwa Inspiration bei Naturreligionen oder im Tierreich, wofür beispielhaft die Hasen oder die Hirsche frü- her Zeichnungen, performative Handlungen mit Ritualcharakter oder auch die Arbeit Honigpumpe am Arbeitsplatz stehen. Rund um die sozialen Bewegungen und die Studentenproteste um 1968 erwachte auch in der breiten Bevölkerung das Bewusstsein für ökologische Fragestellungen. Der bedingungslose Fortschrittsglaube der Nachkriegsgesellschaft kam langsam, aber sicher zu seinem Ende, als die Folgen eines stetigen Anstiegs von Konsum, Produk- tion und Mobilität immer deutlicher und damit einhergehende Prob- leme wie Umweltverschmutzung und Artensterben erkannt wurden. Mit der internationalen Ölpreiskrise 1974 entstanden Diskussionen um alternative Energiequellen und einen nachhaltigeren Umgang mit Ressourcen. In Österreich waren die durch Proteste verhinderte Inbe- triebnahme des Atomkraftwerks Zwentendorf und die Besetzung der Hainburger Au wichtige Momente für die Etablierung einer Ökolo- giebewegung, für die der Baum zu einem Symbol wurde und aus der auch die Partei Die Grünen hervorging. -

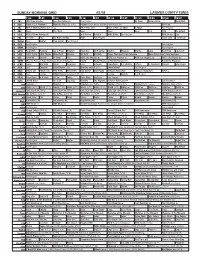

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

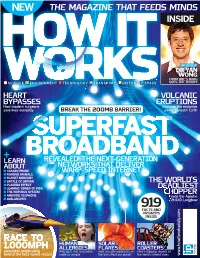

How It Works Issue 9

NEW THE MAGAZINE THAT FEEDS MINDS INSIDE INTERVIEW DR YAN WONG TM FROM BBC’S BANG SCIENCE ■ ENVIRONMENT ■ TECHNOLOGY ■ TRANSPORT HISTORY ■ SPACE GOES THE THEORY HEART VOLCANIC BYPASSES ERUPTIONS How modern surgeons Discover the explosive save lives everyday BREAK THE 200MB BARRIER! power beneath Earth SUPERFAST BROADBAND LEARN REVEALED! THE NEXT-GENERATION ABOUT NETWORKS THAT DELIVER ■ CASSINI PROBE WARP-SPEED INTERNET ■ RAINING ANIMALS ■ PLANET MERCURY ■ BATTLE OF BRITAIN THE WORLD’S ■ PLACEBO EFFECT ■ LEANING TOWER OF PISA DEADLIEST ■ THE NERVOUS SYSTEM CHOPPER ■ ANDROID VS iPHONE Inside the Apache ■ AVALANCHES 919 AH-64D Longbow FACTS AND 9 ANSWERS 0 INSIDE £3.99 4 0 0 2 3 7 1 4 0 ISSN 2041-7322 2 7 7 ISSUE NINE ISSUE RACE TO 9 HUMAN SOLAR ROLLER 1,000MPH ALLERGIES© Imagine PublishingFLARES Ltd COASTERS Awesome engineering Why dust,No unauthorisedhair and pollen copyingHow massive or distribution explosions on Heart-stopping secrets of behind the land speed record make us sneeze the Sun affect our planet the world’s wildest rides www.howitworksdaily.com 001_HIW_009.indd 1 27/5/10 16:34:18 © Imagine Publishing Ltd No unauthorised copying or distribution Get in touch Have YOU got a question you want answered by the How It Works team? Get in touch by… Email: [email protected] Web: www.howitworksdaily.com ISSUE NINE Snail mail: How It Works Imagine Publishing, 33 Richmond Hill The magazine that feeds minds! Bournemouth, Dorset, BH2 6EZ ”FEED YOUR MIND!” Welcome to How It Meet the experts The sections explained Works issue -

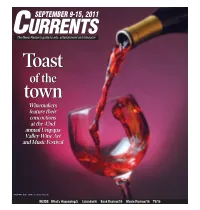

Layout 1 (Page 2)

SEPTEMBER 9-15, 2011 CCURRENTSURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television ToastToast ofof thethe towntown WinemakersWinemakers featurefeature theirtheir concoctionsconcoctions atat thethe 42nd42nd annualannual UmpquaUmpqua ValleyValley WineWine ArtArt andand MusicMusic FestivalFestival MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Book Review/10 Movie Review/14 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 * &YJUt$BOZPOWJMMF 03t*OGPt3FTtTFWFOGFBUIFSTDPN Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING TENMILE An artists’ reception will be held from 5 to 7 p.m. Friday at Remembering GEM GLAM the gallery, 638 W. Harrison St., Roseburg. 9/11 movie, songs Also hanging is art by pastel A special 9/11 remembrance painter Phil Bates, mixed event will be held at 5 p.m. media artist Jon Leach and Sunday at the Tenmile Com- acrylic painter Holly Werner. munity United Methodist Fisher’s is open regularly Church, 2119 Tenmile Valley from 9 to 5 p.m. Monday Road. through Friday. The event includes a show- Information: 541-817-4931. ing of a one-hour movie, “The Cross and the Towers,” fol- lowed by patriotic music and MYRTLE CREEK sing-alongs with musicians Mark Baratta and Scott Van Local artist’s work Atta. hangs at gallery The event is free, but dona- Myrtle Creek artist Darlene tions for musicians’ expenses Musgrave is the featured artist are welcome. Refreshments at Ye Olde Art Shoppe. will be served. An artist’s reception for Information: 541-643-1636. Musgrave will be held from 10 a.m. -

Beuys's Social Sculpture As a Real

A LIVED PRACTICE A LIVED PRACTICE U-topos: Beuys’s Social Sculpture as a Real-Utopia and Its Relation to Social Practice Today Wolfgang Zumdick Two major tendencies, which are somewhat at odds with each other, can be clearly identified in considering Joseph Beuys’s oeuvre. One is the great significance of Beuys’s more traditional forms of artwork whose com- plexity and artistic quality over the years metamorphosed, demonstrat- ing his capacity to develop new forms. The uniqueness of this continuous stream of new forms is apparent if one looks at his work as a whole, start- ing with the earliest drawings and sculptures from the 1940s and leading up to his environments in the 1980s. In fact, it was not only the extraordi- nary aesthetic and imaginative quality of Beuys’s artwork from the 1960s on that so impressed many leading German art historians and art dealers, it was also his unconventional, timely, precise, and unpredictable responses to specific aspects and instances of German society that made his work so fascinating to the artistic avant-garde. His work was the embodiment of a genuine new vanguard. Many people in the art world, however, could neither appreciate nor accept Beuys’s social and political ideas, questioning their artistic significance, even though Beuys himself regarded this social and political dimension as a central aspect of his work. Beuys’s idea of Social Sculpture, which he saw as his most important work of art, was especially undervalued by connoisseurs who nonetheless increasingly deemed Beuys one of the leading artists of the 132 133 figures such as Herder and Goethe, who in turn initiated a period of thinking and writing in Germany later known as German Idealism and Romanticism. -

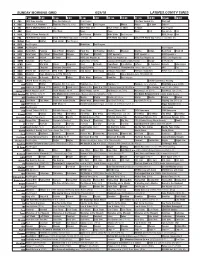

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Friday Morning, Nov. 6

FRIDAY MORNING, NOV. 6 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 78631 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View (N) (cc) (TV14) 64438 Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 297235 (cc) 55693 86051 77902 KOIN Local 6 Early News 81631 The Early Show (N) (cc) (TVG) 65411 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 at 6 58490 74438 99148 (TV14) 15952 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today “Sesame Street” anniversary; Jeff Corwin; Fran Drescher; makeovers. (N) (cc) (TVG) 894186 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 97780 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 28761 Power Yoga Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Big Bird & Snuffy Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 18896 (TVY) 18709 (TVY) 34235 Kid (TVY) 46070 (TVY) 59070 (TVY) 58341 Talent Show. (TVY) 27544 Red Dog 92761 (TVY) 45877 86525 (TVY) 87254 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 79419 Good Day Oregon (N) 58815 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12612 Paid 27457 Paid 63273 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 57186 Key of David Paid 17235 Paid 33761 Paid 52896 Through the Bible Life-Robison Paid 56525 Paid 87983 Paid 31815 Paid 52709 Paid 93457 Paid 94186 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) 62380 66902 65273 Praise-A-Thon (Left in Progress) Fundraising event. -

7000 Oak Trees"

2019 International Conference on Education, Management, Social Science and Humanities Research (EMSSHR 2019) The wizard of the world and his "7000 Oak Trees" Gao Lei Xi'an Academy of Fine Arts, Xi’an Shaanxi, 710065 Keywords: the enchantment of the world, social sculpture, everyone is an artist Abstract: In the modern rational reality, "the enchantment of the world" will become an internal trend in the future. This speaks not only to our continuing confusion about nature and existence, but also, in a fundamental sense, to the need to reshape our increasingly dull and fraying reality. Joseph Beuys, one of Europe's most influential postwar artists, has been hailed as the 20th century's spiritual teacher and "wizard of the world". With his revelation from the mystical culture of the German Romanticism, the salvation of European Christian culture, and the Great Zen of the East, he interprets the artistic revolution of the last century. Among William Boyce's many works, “7000 Oaks” a growing project, reveals William Boyce's meditation on the subtle and mysterious connection between man and nature. It is the most complete embodiment of William Boyce's "social sculpture", i.e. the "everyone is an artist" concept of artistic expansion. Through William Boyce's thinking and practice, art rose to become a force for the fundamental transformation of existence and the world. 1. The enchantment of the world "It is barbarous to write poetry after Auschwitz," German philosopher Theodor Adorno said in a famous criticism published in the collection Prism in 1955. He expressed the paleness and fragility of traditional poetics in the face of reality after the Holocaust. -

Journey Into a Living Being – from Social Sculpture to Platform Capitalism an Exhibition by Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien and Tilman Baumgärtel

Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien Mariannenplatz 2 10997 Berlin 030-90298-1455 Fax -1453 PRESS RELEASE GROUP EXHIBITION Journey into a Living Being – From Social Sculpture to Platform Capitalism An exhibition by Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien and Tilman Baumgärtel With friendly support by the Senatsverwaltung für Kultur und Europa: Ausstellungsfonds für Kommunale Galerien und Fonds für Ausstellungsvergütungen and realised in cooperation with Tamago. Press view: By appointment Duration: 18 May – 16 August 2020 Opening hours: Sun-Wed 10:00–20:00, Thu-Sat 10:00–22:00. Entrance: free of admission The group exhibition JOURNEY INTO A LIVING BEING should have opened at the end of March. Due to the outbreak of the corona pandemic, it had to be postponed and will now be shown at Kunstraum Kreuzberg from 18 May onwards, in compliance with hygiene and distance regulations. When the exhibition was conceived two years ago, it was not possible to foresee the urgent actuality the topic would have in these times of Corona: lock-in, home office, zoom conferences, live streaming on YouTube and other platforms shape our everyday lives while amazon and Lieferando make the profits that smaller businesses are unable to make. Platform capitalism is becoming more and more entrenched in our everyday lives and in work realities. The exhibition takes a critical look at these developments, which have been emerging for years. Kunstraum Kreuzberg presents JOURNEY INTO A LIVING BEING, a group exhibition featuring 32 artists and a discursive program which reflects on the methods used by companies such as YouTube, Google, Fiverr or Amazon Mechanical Turk, whose business model rests on the exploitation of their users’ creative potential. -

R Our Studies of Rome

Rome map Use page 336 and 337 in History Alive books to complete the map and the questions on the back. Chakrika Ryan David Mohammad Madison Areeb Vibha Jonathan Masen Abhi Ronak Daniel Zach Ethan Matt Colin Nolan Zenub Ava Bella Hunter Brad Neha Sarah Carter Our Studies of Rome 1. Geography and Early Development of Rome 2. Rise of the Republic 3. From Republic to Empire 4. Daily Life 5. Origins and Spread of Christianity 6. Learning About World Religions 7. Legacy of Rome Dear Me, + on the back of your KWL, write a short letter to yourself explaining what new things you’ve learned since you last wrote on this sheet! Area Evidence of Greek Influence Today Language Sports/Entertainment Government Astronomy Mathematics Warm up Grab a sheet from the stool and begin filling out the top chart: • What do you know about Rome? • What would you like to know? Try to list 3-5 items in each… For the next 15 images, write down something that comes to mind in your KWL. Rome KWL Grapes What do you know about What do you want to Rome’s… know? G R A **Achievements** P E S Can you figure out the analogies? Dog : Cat :: Bark : _____________ Sparta : Rome :: Helot : _____________ Athens : Rome :: Acropolis : ____________ Alexander : Macedonia :: _____________ : Rome The Height of Rome – 117 CE Geography Challenge • You will need: 1. A worksheet 2. Two colored pencils *different colors* 3. Journeys and History Alive Books around room 4. A small group (2-3 people) Warm up questions 1. How has someone older than you ever influenced you? 2. -

Joseph Beuys 1 Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys 1 Joseph Beuys Joseph Beuys Offset poster for Beuys' 1974 US lecture-series "Energy Plan for the Western Man", organised by Ronald Feldman Gallery - Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York Born May 12, 1921Krefeld, Germany Died January 23, 1986 (aged 64)Düsseldorf Nationality German Field Performances, sculpture, visual art, aesthetics, social philosophy Training Kunstakademie Düsseldorf Joseph Beuys (German pronunciation: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈbɔʏs]; May 12, 1921, Krefeld – January 23, 1986, Düsseldorf) was a German performance artist, sculptor, installation artist, graphic artist, art theorist and pedagogue of art. His extensive work is grounded in concepts of humanism, social philosophy and anthroposophy; it culminates in his "extended definition of art" and the idea of social sculpture as a gesamtkunstwerk, for which he claimed a creative, participatory role in shaping society and politics. His career was characterized by passionate, even acrimonious public debate, but he is now regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.[1] [2] Biography Childhood and early life in the Third Reich (1921-1941) Joseph Beuys was the son of the merchant Josef Jakob Beuys (1888–1958) and Johanna Maria Margarete Beuys (born Hülsermann, 1889–1974). The parents had moved from Geldern to Krefeld in 1910, and Beuys was born there on May 12, 1921. In autumn of that year the family moved to Kleve, an industrial town in the Lower Rhine region of Germany, close to the Dutch border. There, Joseph attended primary school (Katholische Volksschule) and secondary/high- school (Staatliches Gymnasium Cleve, now the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium). His teachers considered him to have a talent for drawing; he also took piano- and cello lessons. -

Social Sculpture Re-Visited by Dorothee Richter (Part 1) and Michael G

Editorial Social Scultpure re-visited Social Sculpture re-visited by Dorothee Richter (part 1) and Michael G. Birchall (part 2) Part 1 We share our interest in Social Practices in the arts. Therefore I initiated a curatorial project for the Postgraduate Programme in Curating, ZHdK, Zürich around the topic of Social Sculptures. The project took place in four different steps over a period of time of one and a half years, the curatorial concept was changed and further developed and produced by the artists, students/ participants and lecturers. The first step was to initiate an archive on artistic practice which an inter- est in communities, which was shown twice, once at the White Space, Zürich and secondly at Kunstmuseum Thun. The archive was curated by Karin Frei Bernasconi, Siri Peyer and myself, with the cooperation of the students of the programme. From this convolute I invited three artists to work with the students for projects related to the notion of Social Sculpture: Szuper Gallery (Susanne Clausen and Pawlo Kerestey), San Keller and Jeanne van Heeswijk. Each of them developed the projects in workshops with the students of the Postgraduate Programme in Curat- ing over a period of about one year. “Social Sculpture” – the German notion even downplays this term as “Soziale Plastik” was coined by Joseph Beuys, as new form of creating art, and influencing society, his expanded notion of the area of the arts was initiated by the confronta- tion with Fluxus practices, when he hosted one of the first Fluxus Festivals in Düs- seldorf. Beuys