David Faber FG Fantin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile: Fred Paterson

Fred Paterson The Rhodes Scholar and theological student who became Australia's first Communist M.P. By TOM LARDNER Frederick Woolnough Paterson deserves more than the three lines he used to get in Who’s Who In Australia. As a Member of Parliament he had to be included but his listing could not have been more terse: PATERSON, Frederick Woolnough, M.L.A. for Bowen (Qld.) 1944-50; addreii Maston St., Mitchelton, Qld. Nothing like the average 20 lines given to most of those in Who’s Who, many with much less distinguished records. But then Fred Paterson had the disadvantage—or was it the distinction?—of being a Communist Member of Parliament— in fact, Australia’s first Communist M.P. His academic record alone should have earned him a more prominent listing, but this was never mentioned:— A graduate in Arts at the University of Queensland, Rhodes Scholar for Queensland, graduate in Arts at Oxford University, with honors in theology, and barrister-at-law. He was also variously, a school teacher in history, classics and mathematics; a Workers’ Educational Association organiser, a pig farmer, and for most o f the time from 1923 until this day an active member of the Communist Party of Australia, a doughty battler for the under-privileged. He also saw service in World War I. Page 50— AUSTRALIAN LBFT REVIEW, AUG.-SEPT., 1966. Fred Paterson was born in Gladstone, Central Queensland in 1897, of a big (five boys and four girls) and poor family. His father, who had emigrated from Scotland at the age of 16, had been a station manager and horse and bullock teamster in the pioneer days of Central Queensland; but for most of Fred’s boyhood, he tried to eke out a living as a horse and cart delivery man. -

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950

82 The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 After the Second World War ended with the defeat of Germany and Japan in 1945, a new global conflict between Communist and non-Communist blocs threatened world peace. The Cold War, as it was called, had substantial domestic repercussions in Australia. First, the spectre of Australians who were committed Communists perhaps operating as fifth columnists in support of Communist states abroad haunted many in the Labor, Liberal and Country parties. The Soviet Union had been an ally for most of the war, and was widely understood to have been crucial to the defeat of Nazism, but was now likely to be the main opponent if a new world war broke out. The Communist victory in China in 1949 added to these fears. Second, many on the left feared persecution, as anti-Communist feeling intensified around the world. Such fears were particularly fuelled by the activities of Senator Joe McCarthy in the United States of America. McCarthy’s allegations that Communists had infiltrated to the highest levels of American government gave him great power for a brief period, but he over-reached himself in a series of attacks on servicemen in the US Army in 1954, after which he was censured by the US Senate. Membership of the Communist Party of Australia peaked at around 20,000 during the Second World War, and in 1944 Fred Paterson won the Queensland state seat of Bowen for the party. Although party membership began to decline after the war, many Communists were prominent in trade unions, as well as cultural and literary circles. -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

We're Not Nazis, But…

August 2014 American ideals. Universal values. Acknowledgements On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. This report was made possible by the generous Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to support of the David Berg Foundation and Arthur & look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Toni Rembe Rock. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s Human Rights First has for many years worked to a vital national interest. America is strongest when our combat hate crimes, antisemitism and anti-Roma policies and actions match our values. discrimination in Europe. This report is the result of Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and trips by Sonni Efron and Tad Stahnke to Greece and action organization that challenges America to live up to Hungary in April, 2014, and to Greece in May, 2014, its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in as well as interviews and consultations with a wide the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. range of human rights activists, government officials, government and private companies to respect human national and international NGOs, multinational rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to bodies, scholars, attorneys, journalists, and victims. demand reform, accountability, and justice. Around the We salute their courage and dedication, and give world, we work where we can best harness American heartfelt thanks for their counsel and assistance. influence to secure core freedoms. We are also grateful to the following individuals for We know that it is not enough to expose and protest their work on this report: Tamas Bodoky, Maria injustice, so we create the political environment and Demertzian, Hanna Kereszturi, Peter Kreko, Paula policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect Garcia-Salazar, Hannah Davies, Erica Lin, Jannat for human rights. -

N. Nome Via Cap Citta 1 Abalotti Simone Via Vicenza 146 36014

N. NOME VIA CAP CITTA 1 ABALOTTI SIMONE VIA VICENZA 146 36014 MALO 2 ACQUASALIENTE MATTEO VIA VALDISSERA 82/A 36033 ISOLA VIC.NA 3 ANDRIAN PAOLO VIA ORSALE 31/1 35040 MERLARA (PD) 4 ANTONELLO GIOVANNA VIA LAMPERTICO 8C 36016 THIENE 5 ANTONIAZZI BRUNO VIA DELL'INDUSTRIA 78 36070 TRISSINO 6 ANTONIAZZI STEFANO VIA BUSIA 7 36034 MALO 7 ARD RICCARDO VIA VITTORIO VENETO 34/B 36050 QUINTO VICENTINO 8 BABOLIN MARA VIA GALIZZI 14 36100 VICENZA 9 BAGGIO FRANCESCA VIA DEI QUARTIERI 83/A 36016 THIENE 10 BALASSO PAOLO VIA CROSARA 67 36042 BREGANZE 11 BANDOLIN LUIGIA VIA PASUBIO 17 36015 Schio 12 BARBIERI ELENA VIA GIACOMO LEOPARDI 2/D 36030 VILLAVERLA 13 BATTISTELLA DANIELA VIA C.TRA' SMIDERLE 2 36015 SCHIO 14 BAU' EMANUELA VIA MICHELONI 10 36030 FARA VIC. 15 BELLO' STEFANIA VIA G.MARCONI 50 36020 POVE D.GRAPPA 16 BENETTI DIEGO VIA DELLO SPORT 36078 VALDAGNO 17 BENETTI GIUSEPPE VIA XXV APRILE 43 36070 CASTELGOMBERTO 18 BENVEGNU' MATTEO VIA MAGRE 13/A 31011 ASOLO 19 BERGAMO GIANLUCA VIA SANTA LUCIA 32/B 36056 TEZZE SUL BRENTA 20 BERLATO LORENZO VIA DON BETTANIN 54 36036 TORREBELVICINO 21 BERNARDELLE ALESSIO VIA PRA' SECCO 79 36010 CARRE' 22 BERNARDELLE GILDO VIA G. MARCHIORO 36033 CASTELNOVO 23 BERNARDI BRUNO VIA G. GALILEI 73 36036 TORRE BEL VICINO 24 BERNARDI MANUELA IRENE VIA STAZIONE 114 36035 MARANO VIC.NO 25 BERNARDOTTO SILVIA VIA F.RANDO 19B 36010 CHIUPPANO 26 BERTOLATI ELISA VIA LISTON S. GAETANO 16/18 36034 MALO 27 BERTOLO CRISTINA VIA SANTISSIMA TRINITA' 206 36015 SCHIO 28 BERTONCELLO PAOLA VIA S. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

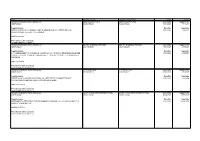

Lotto Operatori Invitati Operatori Aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BISSON AUTO S.P.A

Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BISSON AUTO S.P.A. BISSON AUTO S.P.A. Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02202650244 02202650244 16/06/2021 1.518,27€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato BISSON AUTO S.P.A., GRUMOLO DELLE ABBADESSE (VI) - INTERVENTO DI 31/12/2021 1.246,32€ MANUTENZIONE AUTOMEZZO COMUNALE CIGZ283208993 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BETTIO GABRIELE PER.IND BETTIO GABRIELE PER.IND Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02483070245 02483070245 17/06/2021 2.550,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato P.I. GABRIELE BETTIO, CAMISANO VICENTINO (VI) - INCARICO PROFESSIONALE PER 31/12/2021 2.550,00€ PROGETTO DI ADEGUAMENTO IMPIANTO ELETTRICO EX SCUOLE ELEMENTARI DI SARMEGO CIGZF53223D40 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse FORTE NICOLA FORTE NICOLA Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 03160660241 03160660241 04/06/2021 2.529,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato FORTE NICOLA, QUINTO VICENTINO (VI) - INTERVENTI DI MANUTENZIONE 31/12/2021 2.529,00€ STRAORDINARIA IMPIANTO ELETTRICO SCUOLE MEDIE CIGZBA31F4EFA Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse LA GOCCIA SCARL SERVIZI SOCIALI LA GOCCIA SCARL SERVIZI SOCIALI Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 00882110240 00882110240 30/04/2020 19.734,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato AFFIDAMENTO SERVIZIO DI PULIZIA IMMOBILI COMUNALI ALLA COOP.SOCIALE "LA 31/12/2021 20.894,87€ GOCCIA" DI MAROSTICA. CIGZAD2CBFE47 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse PMP SRL PMP SRL Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02580430029 02580430029 29/01/2021 525,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato PMP S.R.L., 360169 THIENE (VI). -

Elenco Strade Vicenza 2015 04 23.Pdf

PROVINCIA DI VICENZA AREA DIREZIONE – PROGRAMMAZIONE – CONTROLLI – UFFICI DI STAFF SETTORE ECONOMICO FINANZIARIO UFFICIO DEMANIO, PATRIMONIO ED ESPROPRIAZIONI Domicilio Fiscale: Contrà Gazzolle n. 1 - 36100 VICENZA – C.F. e P. IVA 00496080243 Uffici: Palazzo Arnaldi – Contrà Santi Apostoli n. 18 – 36100 Vicenza – Fax: 0444/908436 indirizzo e-mail: [email protected] indirizzo Posta Elettronica Certificata - PEC: [email protected] ELENCO NUMERICO STRADE PROVINCIALI D:\ARCHIVIO\TRASPORTI ECCEZIONALI\ELENCHI STRADE\elenco strade vicenza 2015_04_23.odt Pag. 1 di 14 LUNGHEZZA NUMERO NUMERO COMPLESSIVA DI D'ORDIN DENOMINAZIONE S.P. PERCORSO (INIZIO – FINE) STRADA PERCORSO (IN E METRI) S.S. n° 53 “Postumia” - confine con provincia di 1 SP1 EX POSTUMIA 2.139 Padova verso S. Pietro in Gù S.R. 11 “Padana Superiore” a Creazzo - loc. 2 SP2 ZILERI Piazzon - S.P. n° 36 “Gambugliano” in località Villa 2.510 Zileri S.P. n° 123 “Poianese” a Poiana Maggiore - 3 SP3 COLOGNESE Asigliano Veneto - confine con provincia di Verona 5.239 per Cologna S.P. n° 123 “Poianese” a Poiana Maggiore - 4 SP4 CONTELLENA 7.149 Colleredo - Sossano - S.P. n° 8 “Berico Euganea” S.P. n° 125 “S. Feliciano” - Teonghio - confine con 5 SP5 TEONGHIO 3.213 provincia di Verona verso Spessa S.P. n° 247 “Riviera Berica” località Ponticelli - 6 SP6 CAMPIGLIA Campiglia dei Berici - Colleredo - S.P. n° 4 4.949 “Contellena” S.P. n° 247 “Riviera Berica” in località Ponticelli di 7 SP7 LIONA Agugliaro - Agugliaro - confine con provincia di 4.165 Padova verso Vo' Euganeo S.P. n° 125 “S. Feliciano” - Orgiano - Sossano - interruzione a Barbarano Vicentino all'intersezione con la S.P. -

Mating Disruption for Managing the Honeydew Moth, Cryptoblabes Gnidiella (Millière), in Mediterranean Vineyards

insects Article Mating Disruption for Managing the Honeydew Moth, Cryptoblabes gnidiella (Millière), in Mediterranean Vineyards Renato Ricciardi 1,† , Filippo Di Giovanni 1,†, Francesca Cosci 1, Edith Ladurner 2, Francesco Savino 2, Andrea Iodice 2, Giovanni Benelli 1,* and Andrea Lucchi 1 1 Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Pisa, via del Borghetto 80, 56124 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (F.D.G.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (A.L.) 2 CBC (Europe) srl, Biogard Division, via Zanica, 25, 24050 Grassobbio, Italy; [email protected] (E.L.); [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (A.I.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-050-2216141 † These authors contributed equally. Simple Summary: Cryptoblabes gnidiella has recently become one of the most feared pests in the Mediterranean grape-growing areas. Its expanding impact requires the development of effective strategies for its management. Since insecticide strategy has shown several weaknesses, we developed a pheromone-based mating disruption (MD) approach as a possible sustainable control technique for this pest. Between 2016 and 2019, field trials were carried out in two study sites in central and southern Italy, using experimental pheromone dispensers. The number of adult captures in pheromone-baited traps and the percentage of infestation recorded on ripening grapes were compared among plots treated with MD dispensers, insecticide-treated (no MD) plots, and untreated Citation: Ricciardi, R.; Di Giovanni, plots. Results highlighted that the application of MD may contribute to lowering the damage F.; Cosci, F.; Ladurner, E.; Savino, F.; significantly. However, further studies aimed at clarifying the still little-known aspects of the biology Iodice, A.; Benelli, G.; Lucchi, A. -

Australian Nationalist Ideological, Historical, and Legal Archive

AUSTRALIAN NATIONALIST IDEOLOGICAL, HISTORICAL, AND LEGAL ARCHIVE www.alphalink.com.au/~radnat MISSION STATEMENT (as updated, August 24 2002): This Site is a document archive linked to other Australian Nationalist political and information sites. A few Australian authors are on-line. As further works are prepared for Internet publication, additional Australian authors shall appear here. This document archive shall: (i) Ground Australian Nationalism ideologically and historically; this task is related to the legitimacy of the cause as well as the discussion of its favoured political expressions and historical place and activism; providing an accurate analysis is vital in combatting the misrepresentation of Nationalist ideology and politics by its opponents in politics and the media. (ii) Answer (when appropriate) the State-liberal-political-police propaganda which attempts to delegitimize the Nationalist organizations by an assertion that they have operated, or do operate, in a criminal manner; this task shall be addressed by relevant exposé of various "legal processes" operated against Nationalist leaders and other patriotic identities in the past. This Archive shall be continually updated and maintained as a resource for the instruction of a new generation of Nationalist leaders and activists. Texts of a general relevancy to the development of Australian Nationalist ideology and politics will also be placed upon this site. This includes material drawn from the corpus of Euro-nationalist discourse. The Editors welcome that our attention is drawn to selective material. The Editors will permit some debate around the issue of ideological and political formation and shall not censor any reasonable view on any subject which advances this objective. -

How the National Guard Grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew Am Rgis Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew aM rgis Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Margis, Matthew, "America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15764. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15764 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s progressive army: How the National Guard grew out of progressive era reforms by Matthew J. Margis A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural, Agricultural, Technological, Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Timothy Wolters, Major Professor Julie Courtwright Jeffrey Bremer Amy Bix John Monroe Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Matthew J. Margis, 2016. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my parents, and the loving memory of Anna Pattarozzi,