Qualitative Research Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

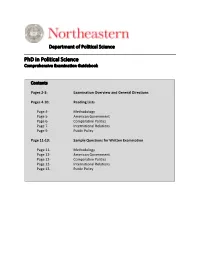

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(S): David A

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(s): David A. Welch Source: International Security , Fall, 1992, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall, 1992), pp. 112-146 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security This content downloaded from 209.6.197.28 on Wed, 07 Oct 2020 15:39:26 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Organizational David A. Welch Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms Retrospect and Prospect 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the publication of Graham Allison's Essence of De- cision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. ' The influence of this work has been felt far beyond the study of international politics. Since 1971, it has been cited in over 1,100 articles in journals listed in the Social Sciences Citation Index, in every periodical touching political science, and in others as diverse as The American Journal of Agricultural Economics and The Journal of Nursing Adminis- tration. -

Theory of International Politics

Theory of International Politics KENNETH N. WALTZ University of Califo rnia, Berkeley .A yy Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California London • Amsterdam Don Mills, Ontario • Sydney Preface This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Political Science Theory is fundamental to science, and theories are rooted in ideas. The National Science Foundation was willing to bet on an idea before it could be well explained. The following pages, I hope, justify the Foundation's judgment. Other institu tions helped me along the endless road to theory. In recent years the Institute of International Studies and the Committee on Research at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, helped finance my work, as the Center for International Affairs at Harvard did earlier. Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and from the Institute for the Study of World Politics enabled me to complete a draft of the manuscript and also to relate problems of international-political theory to wider issues in the philosophy of science. For the latter purpose, the philosophy depart ment of the London School of Economics provided an exciting and friendly envi ronment. Robert Jervis and John Ruggie read my next-to-last draft with care and in sight that would amaze anyone unacquainted with their critical talents. Robert Art and Glenn Snyder also made telling comments. John Cavanagh collected quantities of preliminary data; Stephen Peterson constructed the TabJes found in the Appendix; Harry Hanson compiled the bibliography, and Nacline Zelinski expertly coped with an unrelenting flow of tapes. Through many discussions, mainly with my wife and with graduate students at Brandeis and Berkeley, a number of the points I make were developed. -

A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Advance Access publication June 13, 2006 Political Analysis (2006) 14:227–249 doi:10.1093/pan/mpj017 A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research James Mahoney Departments of Political Science and Sociology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-1006 e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) Gary Goertz Department of Political Science, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 e-mail: [email protected] The quantitative and qualitative research traditions can be thought of as distinct cultures marked by different values, beliefs, and norms. In this essay, we adopt this metaphor toward the end of contrasting these research traditions across 10 areas: (1) approaches to expla- nation, (2) conceptions of causation, (3) multivariate explanations, (4) equifinality, (5) scope and causal generalization, (6) case selection, (7) weighting observations, (8) substantively important cases, (9) lack of fit, and (10) concepts and measurement. We suggest that an appreciation of the alternative assumptions and goals of the traditions can help scholars avoid misunderstandings and contribute to more productive ‘‘cross-cultural’’ communica- tion in political science. Introduction Comparisons of the quantitative and qualitative research traditions sometimes call to mind religious metaphors. In his commentary for this issue, for example, Beck (2006) likens the traditions to the worship of alternative gods. Schrodt (2006), inspired by Brady’s (2004b, 53) prior casting of the controversy in terms of theology versus homiletics, is more explicit: ‘‘while this debate is not in any sense about religion, its dynamics are best understood as though it were about religion. We have always known that, it just needed to be said.’’ We prefer to think of the two traditions as alternative cultures. -

Research Design Skopje 6-7 November 2008

Research Design Skopje 6-7 November 2008 Daniel Bochsler and Lucas Leemann Center for Comparative and International Studies, University of Zurich [email protected]; [email protected] Introduction The goal of this workshop session is to review the current literature on issues of research design in social sciences and to allow the participants to improve on their skills in designing research. The workshop starts off with a short review of some basic principles of scientific research, before turning to two of the main goals of scientific work, namely descriptive and causal inferences. In a second part different research designs are discussed, relying on the basic distinction between experimental and quasi-experimental work. Given that despite the important forays in experimental studies in the social sciences (see Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia, 2006) quasi- experimental designs will be discussed in more detail. Special emphasis will be put on the dangers to our inferences in such quasi-experimental designs. The third part will consist of a discussion of a few chosen research designs to highlight their strengths and weaknesses. Finally, based on the participants own experience, in a short training session they will have to sketch possible research designs for chosen research questions. Plan, readings and literature Most of the literature on which this workshop will rely comes from King, Keohane and Verba (1994), a book that, from a very specific perspective, highlights the similarities between quantitative and qualitative approaches. Needless to say, this book has attracted a series of critiques (e.g., Caporaso, 1995; Collier, 1995; Rogowski, 1995; Tarrow, 1995; Brady and Collier, 2004). -

When Are Arms Races Dangerous? When Are Arms Races Charles L

When Are Arms Races Dangerous? When Are Arms Races Charles L. Glaser Dangerous? Rational versus Suboptimal Arming Are arms races dan- gerous? This basic international relations question has received extensive at- tention.1 A large quantitative empirical literature addresses the consequences of arms races by focusing on whether they correlate with war, but remains divided on the answer.2 The theoretical literature falls into opposing camps: (1) arms races are driven by the security dilemma, are explained by the rational spiral model, and decrease security, or (2) arms races are driven by revisionist adversaries, explained by the deterrence model, and increase security.3 These Charles L. Glaser is a Professor in the Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies at the Uni- versity of Chicago. For their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, the author would like to thank James Fearon, Michael Freeman, Lloyd Gruber, Chaim Kaufmann, John Schuessler, Stephen Walt, the anonymous reviewers for International Security, and participants in seminars at the Program on In- ternational Security Policy at the University of Chicago, the Program on International Political Economy and Security at the University of Chicago, the John M. Olin Institute at Harvard Univer- sity, and the Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia. He also thanks John Schuessler for valuable research assistance. 1. The pioneering study is Samuel P. Huntington, “Arms Races: Prerequisites and Results,” Public Policy, Vol. 8 (1958), pp. 41–86. Historical treatments include Paul Kennedy, “Arms-Races and the Causes of War, 1850–1945,” in Kennedy, Strategy and Diplomacy, 1870–1945 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1983); and Grant T. -

Theories of War and Peace

1 THEORIES OF WAR AND PEACE POLI SCI 631 Rutgers University Fall 2018 Jack S. Levy [email protected] http://fas-polisci.rutgers.edu/levy/ Office Hours: Hickman Hall #304, Tuesday after class and by appointment "War is a matter of vital importance to the State; the province of life or death; the road to survival or ruin. It is mandatory that it be thoroughly studied." Sun Tzu, The Art of War In this seminar we undertake a comprehensive review of the theoretical and empirical literature on interstate war, focusing primarily on the causes of war and the conditions of peace but giving some attention to the conduct and termination of war. We emphasize research in political science but include some coverage of work in other disciplines. We examine the leading theories, their key causal variables, the paths or mechanisms through which those variables lead to war or to peace, and the degree of empirical support for various theories. Our survey includes research utilizing a variety of methodological approaches: qualitative, quantitative, experimental, formal, and experimental. Our primary focus, however, is on the logical coherence and analytic limitations of the theories and the kinds of research designs that might be useful in testing them. The seminar is designed primarily for graduate students who want to understand – and ultimately contribute to – the theoretical and empirical literature in political science on war, peace, and security. Students with different interests and students from other departments can also benefit from the seminar and are also welcome. Ideally, members of the seminar will have some familiarity with basic issues in international relations theory, philosophy of science, research design, and statistical methods. -

Attack and Conquer? Karen Ruth Adams International Anarchy and the Offense-Defense-Deterrence Balance

Attack and Conquer? Attack and Conquer? Karen Ruth Adams International Anarchy and the Offense-Defense-Deterrence Balance Scholars and strate- gists have long argued that offense is easier than defense in some periods but harder than defense in others.1 In the late 1970s, George Quester and Robert Jervis took the ªrst steps toward systematizing this claim.2 Since then, the de- bate about the causes and consequences of the offense-defense balance has been one of the most active in security studies.3 If the relative efªcacy of offense and defense changes over time, states should be more vulnerable to conquest and more likely to attack one another at some times than at others. Speciªcally, when offense is easier than defense, defenders’ military forces should be more likely to collapse or surrender when attacked, and defenders’ political leaders should be more likely to surrender sovereignty in response to military threats. Thus states in offense-dominant eras should be conquered—involuntarily lose the monopoly of force over all of their territory to external rivals—more often than states in defense-dominant eras.4 Given their heightened vulnerability to conquest, states in offense- Karen Ruth Adams is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Louisiana State University. For detailed comments, I thank Richard Betts, Stephen Biddle, Avery Goldstein, Miles Kahler, Susan Martin, Christopher Muste, Mark Peceny, Kenneth Waltz, James Wirtz, and Eugene Wittkopf. For research assistance, I thank Nicole Detraz, Katia Ivanova, and Aneta Leska. 1. For an annotated bibliography, see Michael E. Brown, Owen R. Coté Jr., Sean M. Lynn-Jones, and Steven E.