Woolley, Paul James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Eighteenth-Century French Literature: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Eighteenth-Century Modernities: Present Contributions and Potential Future Projects from EC/ASECS (The 2014 EC/ASECS Presidential Address) by Christine Clark-Evans It never occurred to me in my research, writing, and musings that there would be two hit, cable television programs centered in space, time, and mythic cultural metanarrative about 18th-century America, focusing on the 1760s through the 1770s, before the U.S. became the U.S. One program, Sleepy Hollow on the FOX channel (not the 1999 Johnny Depp film) represents a pre- Revolutionary supernatural war drama in which the characters have 21st-century social, moral, and family crises. Added for good measure to several threads very similar to Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” story are a ferocious headless horseman, representing all that is evil in the form of a grotesque decapitated man-demon, who is determined to destroy the tall, handsome, newly reawakened Rip-Van-Winkle-like Ichabod Crane and the lethal, FBI-trained, diminutive beauty Lt. Abigail Mills. These last two are soldiers for the politically and spiritually righteous in both worlds, who themselves are fatefully inseparable as the only witnesses/defenders against apocalyptic doom. While the main characters in Sleepy Hollow on television act out their protracted, violent conflict against natural and supernatural forces, they also have their own high production-level, R & B-laced, online music video entitled “Ghost.” The throaty feminine voice rocks back and forth to accompany the deft montage of dramatic and frightening scenes of these talented, beautiful men and these talented, beautiful women, who use as their weapons American patriotism, religious faith, science, and wizardry. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Mountaineering Ventures

70fcvSs )UNTAINEERING Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/mountaineeringveOObens 1 £1. =3 ^ '3 Kg V- * g-a 1 O o « IV* ^ MOUNTAINEERING VENTURES BY CLAUDE E. BENSON Ltd. LONDON : T. C. & E. C. JACK, 35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. AND EDINBURGH PREFATORY NOTE This book of Mountaineering Ventures is written primarily not for the man of the peaks, but for the man of the level pavement. Certain technicalities and commonplaces of the sport have therefore been explained not once, but once and again as they occur in the various chapters. The intent is that any reader who may elect to cull the chapters as he lists may not find himself unpleasantly confronted with unfamiliar phraseology whereof there is no elucidation save through the exasperating medium of a glossary or a cross-reference. It must be noted that the percentage of fatal accidents recorded in the following pages far exceeds the actual average in proportion to ascents made, which indeed can only be reckoned in many places of decimals. The explanation is that this volume treats not of regular routes, tariffed and catalogued, but of Ventures—an entirely different matter. Were it within his powers, the compiler would wish ade- quately to express his thanks to the many kind friends who have assisted him with loans of books, photographs, good advice, and, more than all, by encouraging countenance. Failing this, he must resort to the miserably insufficient re- source of cataloguing their names alphabetically. -

(Melanaphis Sacchari) on SORGHUM a Thesis by ERIN

SPECIES COMPOSITION AND ACTIVITY OF THE NATURAL ENEMIES OF SUGARCANE APHID (Melanaphis sacchari) ON SORGHUM A Thesis by ERIN LYNETTE MAXSON Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, James B. Woolley Co-Chair of Committee, Michael Brewer Committee Member, William Rooney Head of Department, David Ragsdale December 2017 Major Subject: Entomology Copyright 2017 Erin Maxson ABSTRACT The sugarcane aphid (Melanaphis sacchari) is an emergent sorghum pest in the southern United States. The objectives of this study were to identify the natural enemy species that are feeding on the aphid in grain sorghum in Texas, track seasonal changes in aphid and natural enemy populations across sorghum hybrids that have differing levels of susceptibility to the aphid, and measure aphid suppression by natural enemies of different size classes. Aphids and natural enemies were sampled on multiple sorghum hybrids at two field locations in south and central Texas over two years. Additionally, aphid suppression by natural enemies of two size classes was evaluated using exclusion cages. Aphids and natural enemies in both locations showed a trend of greater peak abundance on relatively more aphid-susceptible hybrids. At least 19 natural enemy species were present, consisting of parasitoids (Aphelinus sp. and Lysiphlebus testaceipes), lady beetles (Coccinellidae), hoverflies (Syrphidae), lacewings (Chrysopidae and Hemerobiidae), and minute pirate bugs (Anthocoridae). Aphelinus was heavily hyperparasitized by Syrphophagus aphidivorus. Aphelinus and Coccinellidae, the numerically dominant taxa, maintained high activity on resistant sorghum for a longer period than on susceptible sorghum. -

Volume Xxv. No, 2.7 / Red Bank, N. J,, Wednesday

RED BANK REGISTER VOLUME XXV. NO, 2.7 / RED BANK, N. J,, WEDNESDAY. DECEMBER 31. 1902, PAGES 1 TO 8. SANTA CLAUS'S VISIT. OBITUARY. THE TROLLEY ROAD WORK. THREE WILLS. WEDDED AT SHREWSBURY. II ittttta ottermon, Tiro KMtatftt at Hey/tort and Itnr at ENTERtAXNMENTB IN THE RED Willetta Otteraon, aged eleven years, A FEW MEN AND TEAMS NOW Oevan tirore liiHlrtbtitrtl, MISS GRACE HOLMLS MARRIES BANK CHUBCBEI, daughter of William Otterson of Broad EMPLOYED, HiiHiin (Murk of Keyport iiiocU' bcr will REV. JAMES P. 8TOFPLBT, street, lied Bank, died very suddenly on June 10th, 1900. Hiic left #'45 each to Speaking and Hinging By the Hun. Friday, Her death was due to pneu- Will he M*ut to Work n« Hoonher HOiiH, Charles 11., John 1),, Ezra and The Wedding Took Iiare at Kaon day-school Scholars and IHtttrl- monia. Wednesday afternoon shu was as the Uround Hoftrnn Laborer* ThoinuH Chirk, John 1». Chirk 1H alno to YvHterday at the IWotne of the bution of aiftm-M*rements For down town, but she went to bed that tJet Fourteen tents an Hour and gel a bedroom HUII. Mrs. Clark ordered Hride The touple Will Live at Older Folkm, Too, night with a bad cold. Christinas morn- Teatnu Thirty Cent*, that her bedelothrs and clot lung lie di- Jrwy i'ity Itther Writdltigtt. The Christmas exerciseH of the First iiig ehe was worse. She got up and The trolley company that is building vided among her daughUTH, Mary A pretly wedding was solemnized at Method let Sunday-school were held on looked fit her Christ mas presents and a Hue from Key port to Red Hank, with Anna ColeM, wife of TIIOIUHH ColeH Shrewsbury at noon yesterday, when Misa Christmas night. -

![1870-09-22, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5238/1870-09-22-p-2045238.webp)

1870-09-22, [P ]

THE DELAWARE TRIBTHSTE, ‘WILMINGTON, EEL. Tue Home for Friendless Children have . _ Wilmington âc Heading H. R. FINANCIAL AND COMMERCIAL. Publishers’ Department LOCAL NEWS. ceivod a gift of a Howe Sewing Machine from (gduattottiit. INDUSTRY EXTEND rr TO BEADINO. At the last meeting of the Newport Building AND the enterprising agent here, Mr. A. A. McKain. FBOPOBITION ECONOMY The friends of the Home return their warm Beadino, September 19.—A representation of and Loan Association, money Bold at a premium J) E L A W A R E COLLEGE MAKES Wanted. Republican Convention for Humcx County. thanks for the handsome and useful gift. the Beading Board of Trade, composed of leading of 28 per cent. A County Convention of the Republican party manufacturers, had an interview with the direc WORTH A young man of large experience as editor and pr in- NEWARK, DELA WARM, ANI) ‘ in Maryland, desires to form, a business connection of Susbox County will be held at Georgetown, on Lacked Fifteenth Amendment Celebration. tors of tho Wilmington and Beading Bailroad, Dmncsiir .Hi. i'll el *. WEALTH. Tuesday. September 27, 1870, for the purp OX —A celebration of the adoption of the Fifteenth to-day, to urge the completion of the road from Wednesday, Sept. 21.—Meats unchanged. But W 111 he re-opened for the reception of Students some good newspaper. lias a small capital to in- placing in nomination the County Ticket. Tho Amendment will take place at Laurel,on Thursday Birdsboro to Beading, and the directors passed ter 40@45o, eggs 32c, apples, 20(5)39e half peck, WEDNESDAY, September 14th, 187». -

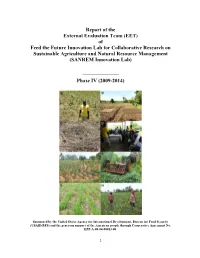

Report of the External Evaluation Team (EET) of Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Collaborative Research on Sustainable Agricul

Report of the External Evaluation Team (EET) of Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Collaborative Research on Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Management (SANREM Innovation Lab) ______________ Phase IV (2009-2014) Sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development, Bureau for Food Security (USAID/BFS) and the generous support of the American people through Cooperative Agreement No. EPP-A-00-04-00013-00. 1 External Evaluation Team (EET) Dr. Rattan Lal, Team Leader Distinguished University Professor of Soil Physics The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Dr. Anita Spring Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology University of Florida, Gainesville, FL Dr. Ross M. Welch Plant physiologist and Lead Scientist, USDA-ARS (Retired) Courtesy Professor, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences Cornell University, Ithaca, NY July 2013 (A) A maize field in Haiti, (B) Layout of an experimental site in Haiti, (C) Maize seedlings emerging through the mulch of Sunn hemp in an experimental plot in Haiti, (D) Discussions by EET with a farmer group in Haiti, (E) Mixed cropping on a mounded seedbed in Ghana, (F) A mechanical roller being used to roll down a cover crop in Cambodia, (G) No-till upland rice directly seeded through a cover crop (Stylosanthes) mulch on a demonstration farm in Cambodia, (H) Two women CAPS adopters viewing the project's maize trials in Cambodia. 2 3 Table of Contents Pages I. Executive Summary 8 A. Assessment of SANREM 8 B. Recommendations for SANREM 10 C. Recommendations for USAID 10 II. Scope of work 12 A. Objective 12 1. Purpose 12 2. Scope of Work 12 III. -

Antique Arms, Armour & Modern Sporting Guns

ANTIQUE ARMS, ARMOUR & MODERN SPORTING GUNS Wednesday 11 & Thursday 12 May 2016 Knightsbridge, London ANTIQUE ARMS, ARMOUR & MODERN SPORTING GUNS Wednesday 11 & Thursday 12 May 2016 Knightsbridge, London Antique Arms & Armour Lots 1 - 393 at 1pm Modern Sporting Guns Lots 400 - 652 at 2pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES Montpelier Street Antique Arms & Armour [email protected] IMPORTANT INFORMATION Knightsbridge, Director Please note that lots of Iranian London SW7 1HH David Williams CUSTOMER SERVICES and Persian origin are subject Monday to Friday www.bonhams.com +44 (0) 20 7393 3807 to US trade restrictions which 8.30am – 6pm +44 (0) 776 882 3711 mobile currently prohibit their import +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 VIEWING [email protected] into the United States, with no Sunday 8 May exemptions. 11am – 3pm Modern Sporting Guns SALE NUMBERS Monday 9 May Head of Department Antique Arms & Armour Similar restrictions may apply 9am – 4.30pm Patrick Hawes 23564 to other lots. 9am - 7pm +44 (0) 20 7393 3815 Tuesday 10 May +44 (0) 781 868 4869 mobile Modern Sporting Guns It is the buyers responsibility 9am – 4.30pm [email protected] 23566 to satisfy themselves that the Wednesday 11 May lot being purchased may be 9am – 12pm (Antique Arms) Administrator CATALOGUE imported into the country of 9am – 4.30pm (Modern Guns) Harriet Munckton £20 destination. Thursday 12 May +44 (0) 20 7393 3947 The United States Government Please see page 2 for bidder 9am - 12pm [email protected] has banned the import of ivory information including after-sale into the USA. Lots containing collection and shipment BIDS Junior Cataloguer ivory are indicated by the +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Max Quigley symbol Ф printed beside the lot Please see back of catalogue +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7393 3816 number in this catalogue. -

Ocm39986872-1928-HB-1254.Pdf

HOUSE .... No. 1254 Cfje Commontoealtt) of Qfjassacftusetts In the Year One Thousand Nine Hundred and Twenty-Eight. EXTRACTS FROM THE JOURNALS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE SENATE RELATING TO THE DEATH OF JAMES W. KIMBALL, CLERK OF THE HOUSE FROM 1897 TO 1928. Journal of the House, Wednesday, April 4, 1928. Met according to adjournment, at two o’clock p.m. Prayer was offered by the Chaplain, Reverend Harry W. Kimball, as follows: Almighty God, our Heavenly Father, almost daily we are reminded that our years upon this earth are few, and that the swiftly flying shuttle of time will soon bring to each one the end of his brief stay here. Now, in these moments of silence, with tender hearts and with friendly memories we recall him who during the long long years has served this House so faithfully as its Clerk. Many there are who must do the routine work of the world and care for its many details, else there would be chaos; and this House owes to him who has served it so well a debt beyond measure. But we rejoice that, although for him the laborer’s task is o’er, we have the faith that on earth is only the broken arc and that over yonder must be the perfect round. For him, all the withheld com- pletions of the life here are to be fulfilled in that great spiritual adventure upon -which he has embarked. And so He is not dead, this friend, not dead But in the path we mortals tread Got some few trifling steps ahead And nearer to the end; So that you too, once, past the bend, Shall meet again, as face to face, this friend You fancy dead. -

Historical Group Occasional Paper 8

‘the first example … of an extensive scheme of pure scientific medical investigation’: Thomas Beddoes and the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol, 1794 to 1799 Frank A.J.L. James Department of Science and Technology Studies, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, England Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, W1S 4BS, England [email protected] The Eighth Wheeler Lecture Royal Institution, 12 October 2015 RSCHG Occasional Paper No. 8, published November 2016 ISBN: 2050-0424 Series Editor: Dr Anna Simmons ORCID identification number (http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0499-9291) Acknowledgements I thank the following archives for permission to study manuscripts and other documents in their collections: Library of Birmingham (LoB), Cornwall Record Office (CRO), Wedgwood Museum (WM), The National Archives (TNA), Bristol Record Office (BRO), British Library (BL), National Library of Ireland (NLI), Bedfordshire and Luton Archive Service (BALAS), the Royal Institution (RI), Natural History Museum (NHM), the Royal Society of London, the Linnean Society, Bristol Central Library, McGill University, Chatsworth, Lambton Park and the Bodleian Library. Letters written by Humphry Davy are freely available on-line at <www.davy-letters.org.uk> as part of the project to publish them by the end of the decade. In the meantime, this paper cites their archival or printed locations. I thank the Research Group of the STS Department at University College London for many valuable comments on an earlier draft. Note to Readers Because of the tendency of the Wedgwood, Watt and Boulton families to use the same forenames in succeeding generations, both the fore and surnames of correspondents are given consistently in the notes. -

Annual Report 2012–13

60 Memores MestoesAnnual Report 2012–13 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 2012–13 SENIOR StAFF 2012–13 BOARD OF TRUSTEES From the Head of School Susan B. Lair, PhD Susan B. Lair, PhD From the Head of School 01 Head of School Head of School Don Hicks The Reverend Stuart A. Bates From the Chair of the Board 02 Associate Head of School Rector Susan B. Lair, PhD Director of Physical Education and Athletics Vanessa Sendukas Financial Report 03 Stephen Lovejoy Chair Head of Middle School Mark T. Terry Wolves Against Hunger 04 Elisse Hayes-Karlsson Vice Chair Head of Lower School Thomas E. Gottsegen Founder’s Day 06 Michelle Symonds Secretary Head of Primary School Edward M. Ondarza Diamond Anniversary Gala 08 Margaret Ann Casseb Treasurer Of the eighty-three students who graduated Head of Admissions in 2013, nearly fifty percent of them started as St. Francis 11 Festival Day * Glenn A. Ballard Melinda Guthrie Frederick W. Brazelton St. Francis students in kindergarten or earlier: Head of Advancement Outstanding Volunteer Award 14 Allison Broadnax • 16 started in the Pre-Primary program Staci Thompson Jeannie Rich Chandler • 5 started in Primary I Head of Educational Services We Care Day 15 John E. Chandler • 6 started in Primary II Vance Ulsh Catharine Faulconer • 1 started in Bridge Woolrich Award Winners 16 Head of Business and Operations Mehrnaz S. Gill Stephen W. Herod • 12 started in Kindergarten Gifts—Annual Fund 18 Kelly Huff You can read about seven of those students Michael R. Jamieson on page four of this annual report. Winners of Gifts—Financial Aid 24 Neil M. -

Seed System Security Assessment Haiti

Seed System Security Assessment HAITI R Seed System Security Assessment HAITI An assessment funded by: The United States Agency for International Development/ Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance August 2010 R Core Research Team International Center for Tropical Louise Sperling Agriculture (CIAT) Catholic Relief Services / Dina Brick Caritas J. Simon Ludger Joseph Benor Montgerard Mykel Louis Francois Yueto Nicolas Claudio SNS-MARDNR Emmanuel Prophete University of East A nglia/ Shawn McGuire International Development U N-FAO Philippe LeCoent Javier Escobedo Etienne Peterschmitt Carline Jean-Paul Gary Arestil Fritz Arne World Concern Bunet Exantus Pierre Duclona World Vision Donard Vyuoda Carine Bernard Chris Asanzi ACDI/VOCA Gardy Fleurantin Save the Children Mathieu Mickens Derival Guertho Jean Raoul Dominique Independent consultants Melinda Smale Budry Bayard, Agroconsult Dennis Shannon, Auburn University ii SEED SYSTEM SECURITY ASSESSMENT HAITI Acknowledgements Support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) made this work possible. In Washington, D.C., we greatly appreciate the financial backing and intellectual contributions of Julie March, Laura Powers, Eric Witte, David Delgado, Adam Reinhardt, Phillip Steffen and Ben Swartley. In Haiti, Julie Leonard, Al Dwyer, John Kimbough, Dennis McCarthy and James Woolley gave key insights at important points of the analysis. The management teams of the multiple and varied field partners were supportive, not just for conducting a seed security analysis but also