Greater New Orleans New Greater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With Leadership from Iftikhar Ahmad, Armstrong International Growing By

Vol. 24, No. 6 Kenner’s Community Newspaper Since 1991 JUNE 2015 Kenner traffic With leadership from Iftikhar Ahmad, Armstrong International growing concerns being by leaps and bounds addressed as design By Allan Katz work begins on new Armstrong New Orleans International Airport is Louisiana’s largest airport processing over 80.3 per- airport access road cent of all passengers traveling into the state. The air- port is also the region’s largest asset having a $5.3 bil- An ordinance spelling out the details of a lion economic impact on the regional economy in 2013 “Memorandum of Understanding” between Kenner as found in a recent economic study by economist Dr. and the New Orleans Aviation Board, in advance of a Timothy Ryan. In the five years since Iftikhar Ahmad $7 million project to build a new, four-lane airport ac- was named to the top job at Louis Armstrong New Or- cess road and make other traffic improvements, was leans International Airport, the Kenner-based facility introduced at the Kenner City Council meeting held has shown an incredible growth spurt. Still to come is on April 23, 2015. a new $650 million North Terminal with construction The new access road is needed because con- slated to begin later this year. struction is expected to begin this summer on a Armstrong International was serving 7.7 million $650 million project to build a new North Terminal passengers in 2009. In 2010, Ahmad’s first year at the at Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Air- helm of the airport, the passenger count jumped to port with two concourses and 30 gates along with a $8.2 million. -

2019 Annual Budget, General Fund Revenues Are Estimated at $98.2 Million

JEFFERSON PARISH, LOUISIANA 2019 PROPOSED BUDGET JEFFERSON PARISH OFFICIALS Jefferson Parish President Michael S. Yenni MEMBERS, JEFFERSON PARISH COUNCIL Christopher L. Roberts Councilman-at-Large, Division A Council Chairman Cynthia Lee-Sheng Ricky J. Templet Councilwoman-at-Large, Division B Councilman, 1st District Paul D. Johnston Mark D. Spears, Jr. Councilman, 2nd District Councilman, 3rd District Dominick F. Impastato, III Jennifer Van Vrancken Councilman, 4th District Councilwoman, 5th District Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguishing Budget Presentation Award to Jefferson Parish, Louisiana for its Annual Budget for the fiscal year beginning January 1, 2018. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as a financial plan, as an operations guide, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. 2019 Jefferson Parish Annual Budget i Table of Contents by Function Description Page Description Page Budget Award i Public Safety (Cont.) Table of Contents ii Board of Zoning Adjustments 115 Transmittal Letter 1 Inspection & Code Enforcement 117 Administrative Adjudication 119 Parish Profile Bureau of Administrative Adjudication 121 Parish Profile 5 Dept of Property Maint Zoning/Quality of Life 122 -

Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers

Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers November 1997 Jim Lande Katie Rangos Industry Analysis Division Common Carrier Bureau Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC 20554 This report is available for reference in the Common Carrier Bureau's Public Reference Room, 2000 M Street, N.W. Washington DC, Room 575. Copies may be purchased by calling International Transcription Service, Inc. at (202) 857-3800. The report can also be downloaded [file name LOCAT-97.ZIP] from the FCC-State Link internet site at http://www.fcc.gov/ccb/stats on the World Wide Web. The report can also be downloaded from the FCC-State Link computer bulletin board system at (202) 418-0241. Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers Contents Introduction 1 Table 1: Number of Carriers Filing 1997 TRS Fund Worksheets 7 by Type of Carrier and Type of Revenue Table 2: Telecommunications Common Carriers: 9 Carriers that filed a 1997 TRS Fund Worksheet or a September 1997 Universal Service Worksheet, with address and customer contact number Table 3: Telecommunications Common Carriers: 65 Listing of carriers sorted by carrier type, showing types of revenue reported for 1996 Competitive Access Providers (CAPs) and 65 Competitive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs) Cellular and Personal Communications Services (PCS) 68 Carriers Interexchange Carriers (IXCs) 83 Local Exchange Carriers (LECs) 86 Paging and Other Mobile Service Carriers 111 Operator Service Providers (OSPs) 118 Other Toll Service Providers 119 Pay Telephone Providers 120 Pre-paid Calling Card Providers 129 Toll Resellers 130 Table 4: Carriers that are not expected to file in the 137 future using the same TRS ID because of merger, reorganization, name change, or leaving the business Table 5: Carriers that filed a 1995 or 1996 TRS Fund worksheet 141 and that are unaccounted for in 1997 i Introduction This report lists 3,832 companies that provided interstate telecommunications service as of June 30, 1997. -

Final Staff Report

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Summary of Uptown and Carrollton Local Historic District Proposals: The Historic Preservation Study Committee Report of April 2016, recommended the creation of the Uptown Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by the Mississippi River, Lowerline Street, South Claiborne Avenue and Louisiana Avenue, and the creation of the Carrollton Local Historic District with boundaries to include the area generally bounded by Lowerline Street, the Mississippi River, the Jefferson Parish line, Earhart Boulevard, Vendome Place, Nashville Avenue and South Claiborne Avenue. These partial control districts would give the Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC) jurisdiction over demolition. Additionally, it would give the HDLC full control jurisdiction over all architectural elements visible from the public right-of-way for properties along Saint Charles Avenue between Jena Street and South Carrollton Avenue, and over properties along South Carrollton Avenue between the Mississippi River and Earhart Boulevard. Recommendation: The City Planning Commission staff recommends approval of the Carrollton and Uptown Local Historic Districts as proposed by the Study Committee. Consideration of the Study Committee Report: City Planning Commission Public Hearing: The CPC holds a public hearing at which the report and recommendation of the Study Committee are presented and the public is afforded an opportunity to consider them and comment. City Planning Commission’s recommendations to the City Council: Within 60 days after the public hearing, the City Planning Commission will consider the staff report and make recommendations to the Council. -

The Jefferson Parish Comprehensive Plan

This document is designed to be printed double-sided. This is the back of the cover and is intentionally blank. Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 2. WHO WE ARE ....................................................................... 5 3. WHAT WE SAID.................................................................. 11 4. OUR VISION ....................................................................... 13 5. LAND USE ......................................................................... 19 6. HOUSING ........................................................................... 39 7. TRANSPORTATION ............................................................ 47 8. COMMUNITY FACILITIES & OPEN SPACE .......................... 57 9. NATURAL HAZARDS & RESOURCES ................................. 71 10. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ............................................ 79 11. ADMINISTRATION & IMPLEMENTATION ......................... 83 APPENDICES A: COMMUNITY PROFILE B: OPPORTUNITIES & CONSTRAINTS C: IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS SINCE 2003 D: UPDATE PROCESS Envision Jefferson 2040 Page i As adopted on November 6, 2019 Prepared by: Under the guidance of the Comprehensive Plan Administration of Update Steering Committee appointed by the Parish Michael S. Yenni, Parish President President and Councilmembers Walter R. Brooks, Chief Operating Officer Bruce Layburn Michael J. Power, Esq., Chief Administrative Bruce Richards Assistant, Development Lloyd Tran Jefferson Parish Planning Department -

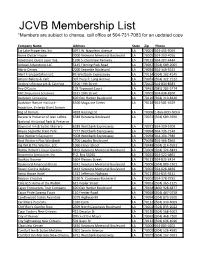

JCVB Membership List *Members Are Subject to Change, Call Office at 504-731-7083 for an Updated Copy

JCVB Membership List *Members are subject to change, call office at 504-731-7083 for an updated copy Company Name Address State Zip Phone 1st Lake Properties, Inc. 4971 W. Napoleon Avenue LA 70001 504-455-5059 Acme Oyster House 3000 Veterans Memorial Boulevard LA 70005 504-309-4056 Adventure Quest Laser Tag 1200 S. Clearview Parkway LA 70123 504-207-4444 Airboat Adventures LLC 5145 Fleming Park Road LA 70067 (504) 689-2005 Alario Center 2000 Segnette Boulevard LA 70094 504-349-5525 Alert Transportation LLC #3 Westbank Expressway LA 70114 (504) 362-4145 Amore Bakery & Cafe 307 Huey P. Long Avenue LA 70053 (504) 322-2122 Andrea's Restaurant & Catering 3100 19th Street LA 70002 504-834-8583 Any O'Cajun 103 Tapwood Court LA 70461 (985) 285-3774 ARC Document Solutions 3521 20th Street LA 70002 504-838-8300 Audubon Limousine 600 Oak Harbor Boulevard LA 70126 (504) 210-8340 Audubon Nature Institute - 6500 Magazine Street LA 70118 504-581-4629 Aquarium, Entergy Giant Screen Bag of Donuts 4828 Hastings St LA 70006 1-866-BOD-NOLA Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte 6588 Barataria Boulevard LA 70072 (504) 689-3690 National Historical Park & Preserve Baymont Inn & Suites Marrero 6589 Westbank Expressway LA 70072 504-309-5700 Bayou Segnette State Park 7777 Westbank Expressway LA 70094 504-736-7140 Best Western Bayou Inn 9008 Westbank Expressway LA 70094 504-304-7980 Best Western Plus Westbank 1700 Lapalco Boulevard LA 70058 504-366-5369 Big Wil & The Warden, LCC 1060 Elmer Street LA 70448 (504) 214-5591 Bobby Hebert's Cajun Cannon 4101 Veterans Memorial Boulevard LA 70001 (504) 324-6841 Bonomolo Limousine, Inc. -

Jefferson Parish Council

2019 Jefferson Parish, Louisiana Comprehensive Annual Financial Report far the year ended December 31, 2019 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT JEFFERSON PARISH, LOUISIANA Year Ended December 31, 2019 Prepared By: DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE JEFFERSON PARISH, LOUISIANA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTORY SECTION LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL ................................................................................................................................................................ V GFOA CERTIFICATE OF ACHIEVEMENT ....................................................................................................................................... XXI SELECTED OFFICIALS OF THE PARISH OF JEFFERSON .......................................................................................................... XXII ADMINISTRATION ORGANIZATIONAL CHARTS ......................................................................................................................... XXVI DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING ORGANIZATIONAL CHART ................................................................................................. XXVII FINANCIAL SECTION INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT .................................................................................................................................................. 1 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................................ -

Louisiana Freight Mobility Plan December 2015

Louisiana Freight Mobility Plan December 2015 prepared for prepared by Louisiana Freight Mobility Plan prepared for Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development prepared by CDM Smith Inc. December 2015 LOUISIANA FREIGHT MOBILITY PLAN Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Summary of Investment Recommendations ............................................................................. 1-2 1.1.1 Capital Investments ...................................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Summary of Policy and Program Recommendations ................................................................ 1-2 1.2.1 Policy recommendations .............................................................................................. 1-3 1.2.2 Program recommendations .......................................................................................... 1-3 2. STRATEGIC GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Federal Requirements ............................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Coordination with Relevant Plans ............................................................................................. 2-2 2.2.1 Statewide Transportation Plan ..................................................................................... 2-2 2.2.2 Other -

Johnson: Local Recovery Management Framework

Johnson: Local Recovery Management Framework International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters August 2014, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 242–274. Developing a Local Recovery Management Framework: Report on the Post-Disaster Strategies and Approaches Taken by Three Local Governments in the U.S. Following Major Disasters Laurie A. Johnson Laurie Johnson Consulting | Research Email: [email protected] Comparative case studies of post-disaster recovery are limited, and even fewer have explored organizational approaches to disaster recovery, especially local governments. This paper describes research on the post-disaster strategies and approaches taken by three local governments in the U.S. following major disasters: Los Angeles, California (following the 1994 Northridge earthquake); Grand Forks, North Dakota (following the 1997 Red River flood); and New Orleans, Louisiana (following 2005 Hurricane Katrina). The management practices, recovery timelines, and resulting outcomes were examined for each city. This research proposes a local recovery management framework that can extend the Incident Command System (ICS)-based emergency management structure into recovery, helping to standardize recovery management practices and improve local government effectiveness in recovery. Such a model has diagnostic application to determine gaps in local government capabilities to manage post-disaster recovery and identify needed support and resources—both financial and technical; it can also serve as a framework for recovery exercises and training. Keywords: Local government, Public management, Disaster recovery, Recovery management, Recovery planning. Introduction When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005, there were a limited number of professionals in the U.S. who had faced the difficult task of managing local government recovery following a major, urban disaster. -

La Mare a Bore at Center Left

Geographies of New Orleans A 'Lake' in Broadmoor? Natural Paradise Once Graced Uptown's Last Open Tract Richard Campanella Contributing writer, GEOGRAPHIES OF NEW ORLEANS Published in the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate, November 1, 2020, page A1 Conversations with older residents of the Broadmoor and Fontainebleau neighborhoods often prompt recollections of a “lake” in that vicinity prior to its urbanization. Indeed, a 1922 aerial photograph shows a large undeveloped tract—the last in the area—between Jefferson and Nashville avenues, going back from South Claiborne Avenue to Gert Town. Having subsided to a few feet below sea level, those open fields probably accumulated runoff after heavy rains, creating what looked like what many secondary sources describe as a “twelve-acre lake” in Broadmoor. But if we go back a century earlier, there turns out to be more to the story than a muddy field. Descriptive evidence comes from the pen of famed lawyer and narrative historian Charles Gayarré, who grew up on the plantation encompassing that low spot, and wrote of his memories in an 1886 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article titled “A Louisiana Sugar Plantation of the Old Regime.” Gayarré was the grandson of Etienne de Boré, the man widely credited—thanks in part to Gayarré’s own dramatized recounting—with figuring out how to granulate locally grown sugarcane juice. That 1795 breakthrough led to a massive expansion of sugar cultivation in lower Louisiana, and of the institution of slavery on which it depended. De Bore’s plantation extended from the present-day 6000 to 6300 blocks of Tchoupitoulas Street straight back to what is now the intersection of Nashville Avenue and Earhart Expressway, an area that includes the aforementioned tract that was still undeveloped as of 1922. -

A Message from Director Mark Cooper

VOLUME 2 ISSUE 2 APRIL 2009 A MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR MARK COOPER It’s hard to believe hurricane season is right around the corner. While there RACE FOR THE 2 CURE were many successes last hurricane season, there’s always room for improve- EMAC DEPLOY- 3 ment. GOHSEP, other state agencies and the parishes have been hard at MENTS work evaluating policy and procedure over the past several months; especially OPS UPDATE 3 related to transportation and sheltering. INSIDE THIS ISSUE UPCOMING 4 GOHSEP continues to expand upon its “Get a Game Plan” campaign. When TRAINING OP- PORTUNITIES hurricane season gets kicked off, we plan to unveil new Public Service An- LSU CLASS 4 nouncements, an all-hazards coloring book for kids created by GOHSEP’s VISIT Michael Verrett (a published author and artist) and a mascot. We hope these 09 DIRECTORS 5 tools will continue to help us educate people on what to do in the event of an emergency. WORKSHOP VIRTUAL LA 5 So as we gear up for what could be another busy hurricane season, GOHSEP will continue to work with HELPFUL HINTS the parishes in every way possible to protect the citizens of Louisiana 09 DIRECTOR’S 6 WORKSHOP 7 PHOTOS PARISHES TO RECEIVE USAR FUNDING GOHSEP EDUCA- 8 TIONAL OUT- REACH This month, Governor Bobby Jindal and GOHSEP Rouge, and Shreveport-Bossier City regions will spon- JORDANIAN 8 Director Mark Cooper announced $18.8 million sor three US&R task forces – and the $1.32 million PARLIAMENT in Homeland Security Grant Funding will be will be equally divided among each region – a total VISIT awarded to enhance law enforcement, fire ser- of $440,000 each. -

Crossing the 17Th Street Canal Exploring Metairie by Kim Ranjbar

Crossing the 17th Street Canal Exploring Metairie by Kim Ranjbar 54 Louisiana Kitchen & Culture | January / February 2018 MyLouisianaKitchen.com Metairie prides itself on the family-friendly atmosphere that pervades the annual Family Gras event pictured above. Unless otherwise noted, photos courtesy the Jefferson Parish Convention and Visitors Bureau. seemingly emingly endless rows of well-manicured lawns, cul-de-sacs brimming with playing kids, tidy homes, and neat gardens … Metairie is a lot like suburbs all over the country. Strip malls hug the edges of orderly communities, and schools are wrapped securely within residential zones. Small neighborhoods Withpour out onto higher-traffic, multi-lane strips lined with everything anyone would need from grocery stores and gas stations to restaurants, malls, and car dealerships. Metairie is a shining example of what it means to be a suburbanite, except when it’s not. … January / February 2018 | Louisiana Kitchen & Culture 55 Destination: Metairie A suburb of New Orleans separated by the 17th Street oldest road in the Greater New Orleans area. Commercial Canal, Metairie is the largest community in Jefferson Parish, buildings and high-end residences rose up around the road with a population of nearly 160,000, and the fifth largest and its meandering path (very) loosely delineates what is CDP (census-designated place) in the country. In the early now referred to as “Old Metairie,” a term that has become 18th century, French settlers were the first Europeans to something of a sticking point between the residents of both colonize the area now known as Metairie Ridge, a natural “old” and “new” areas of town.