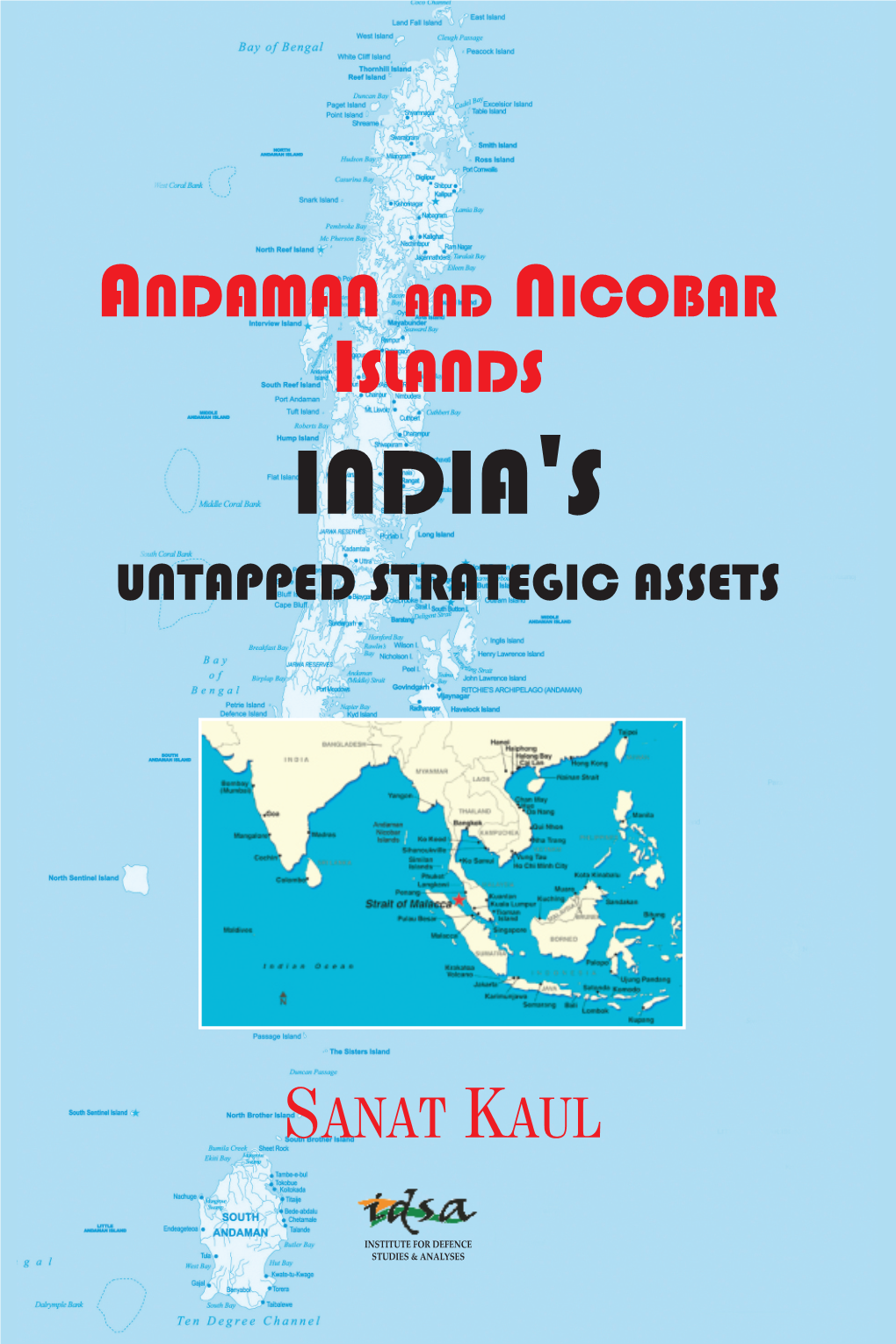

Andaman and Nicobar Islands India’S Untapped Strategic Assets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep 22 nd July, 2014 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, New Delhi – 110002 CONTENTS CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER- II: METHODOLOGY FOLLOWED FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE TELECOM INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIRED 10 CHAPTER- III: TELECOM PLAN FOR ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 36 CHAPTER- IV: COMPREHENSIVE TELECOM PLAN FOR LAKSHADWEEP 60 CHAPTER- V: SUPPORTING POLICY INITIATIVES 74 CHAPTER- VI: SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 84 ANNEXURE 1.1 88 ANNEXURE 1.2 90 ANNEXURE 2.1 95 ANNEXURE 2.2 98 ANNEXURE 3.1 100 ANNEXURE 3.2 101 ANNEXURE 5.1 106 ANNEXURE 5.2 110 ANNEXURE 5.3 113 ABBREVIATIONS USED 115 i CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION Reference from Department of Telecommunication 1.1. Over the last decade, the growth of telecom infrastructure has become closely linked with the economic development of a country, especially the development of rural and remote areas. The challenge for developing countries is to ensure that telecommunication services, and the resulting benefits of economic, social and cultural development which these services promote, are extended effectively and efficiently throughout the rural and remote areas - those areas which in the past have often been disadvantaged, with few or no telecommunication services. 1.2. The Role of telecommunication connectivity is vital for delivery of e- Governance services at the doorstep of citizens, promotion of tourism in an area, educational development in terms of tele-education, in health care in terms of telemedicine facilities. In respect of safety and security too telecommunication connectivity plays a vital role. -

Assessment of Fresh Water Resources for Effective Crop Planning in South Andaman District

J Krishi Vigyan 2018, 7 (Special Issue) : 6-11 DOI : 10.5958/2349-4433.2018.00148.4 Assessment of Fresh Water Resources for Effective Crop Planning in South Andaman District B K Nanda1, N Sahoo2, B Panigrahi3 and J C Paul4 ICAR-KVK, Port Blair (Andaman and Nicobar Group of Islands) ABSTRACT The rainfall data for 40 yr from 1978 to 2017 of the rainfed tropical islands of South Andaman district of Andaman and Nicobar group of islands were analyzed to find out the weekly effective rainfall. Weekly and monthly effective runoff was calculated by following the US Soil Conservation Service - Curve Number (SCS-CN) method. The value of weekly effective rainfall and monthly effective runoff at different level of probabilities was obtained with the help of ‘FLOOD’ software. The sum of effective rainfalls of standard meteorological weeks from 18th to 48th gives the value of fresh water resource availability during kharif season and the same value at 80 percent level of probability was estimated to be 2.07 X105 ha.m. The sum of expected runoff of every month resulted due to the effective rainfall gives the water resource availability during rabi season and its value at 80 percent level of probability was found to be 4.8 X 103 ha.m. All these information will immensely help the farmers, policy makers, planners and researchers to prepare a comprehensive crop action plan for the South Andaman district to make the agriculture profitable and sustainable. Key Words: Curve number, Effective rainfall, Fresh water resources, Storage capacity, Tropical islands INTRODUCTION the Nicobar Islands, which is separated by 10o Small islands are prevalent in the humid channel. -

BOBLME-2011-Ecology-07

BOBLME-2011-Ecology-07 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. BOBLME contract: PSA-GCP 148/07/2010 For bibliographic purposes, please reference this publication as: BOBLME (2011) Country report on pollution – India. BOBLME-2011-Ecology-07 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Bay of Bengal Coast of India 1 1.1 Biogeographical Features 1 1.2 Coastal Ecosystems of the Bay of Bengal Region 8 1.3 Coastal activities of high economic value in terms of GDP 19 Chapter 2 Overview of sources of pollution 33 2.1 Land based Pollution (Both point and non-point sources of 33 pollution) 2.2 Sea/ Marine-based Pollution 40 Chapter 3 Existing water and sediment quality objectives 43 and targets 3.1 Introduction 43 3.2 Wastewater generation in coastal areas 43 Chapter 4 The National Program Coastal Ocean Monitoring 49 and Prediction System 4.1 Mapping hotspots along the coast 49 4.2 Time series analysis and significant findings 53 4.3 Role of Ministries 67 4.3.1 Ministry of Environment and -

Srjis/Bimonthly/Dr. Sushim Kumar Biswas (5046-5055)

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/DR. SUSHIM KUMAR BISWAS (5046-5055) SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF MIGRANT MUSLIM WORKERS IN ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS Sushim Kumar Biswas, Ph. D. HOD, Department of Economics, Andaman College (ANCOL), Port Blair Abstract Socio-economic status (SES) is a multidimensional term. Today SES is deemed to be a hyper - dimensional latent variable that is difficult to elicit. Socioeconomic status is a latent variable in the sense that, like mood or well -being, it cannot be directly measured (Oakes & Rossi, 2003) and it is, some-what, associated with normative science. Finally, it converges to the notion that the definition of SES revolves around the issue of quantifying social inequality. However, it poses a serious problem for the researcher to measure the socio-economic status of migrant workers for short duration during the course of the year. Even in the absence of a coherent national policy on internal migration, millions of Indians are migrating from one destination to another with different durations (Chandrasekhar, 2017). The Andaman & Nicobar Islands(ANI) is no exception and a large number of in-migration is taking place throughout the year. Towards this direction, an attempt has been made to examine the socio-economic profile of migrant Muslim workers who have come to these Islands from West Bengal and Bihar in search of earning their livelihood. An intensive study has been conducted to assess their socio-economic well-being, literacy, income, health hazards, sanitation & medical facilities, family size, indebtedness, acculturation, social status, etc. This study reveals that their socio-economic profile in these Islands are downtrodden, nevertheless they are in a better state than their home town. -

CAR NICOBAR ISLAND Sl.No

CAR NICOBAR ISLAND Sl.No. Particulars 31.12.2006 1. Area (Sq Km) 126.90 2. Census Villages (2001Census) 16 (i) Inhabited 16 1Mus 2 Teetop 3 Sawai 4 Arrong 5Kimois 6 Kakana 7IAF Camp 8 Malacca 9Perka 10 Tamaloo 11 Kinyuka 12 Chuckchucha 13 Tapoiming 14 Big Lapati (Jayanti) 15 Small Lapati 16 Kinmai (ii) Uninhabitted NIL 3. Revenue Villages NIL 4. Panchayat Bodies NIL 5. House Holds (2001 Census) 3296 6. Population (2001 Census) 20292 Male 10663 Female 9629 7. ST Population (2001 Census) 15899 Male 7914 Female 7985 8. Languages Spoken Nicobari & Hindi 9. Main Religion Hinduism, Christianity & Islam 10. Occupation – Main Workers (2001 Census) (i) Cultivators 24 (ii) Agricultural Labourers 9 (iii) Household Industries 2288 (iii) Other Workers 3671 11. Villages provided with piped water 16 supply 12. Health Service (a) Institutions (i) Hospital 1 (ii) Sub Centre 5 (iii) Dispensary 1 (b) Health Manpower (i) Doctors 10 (ii) Nurses/Midwives/LHVs 37 (iii) Para Medical Staff 60 (c) Bed Strength 113 13. Industries Industrial Centre 1 Industrial Estate Nil Industries Registered 13 54 ISLAND-WISE STATISTICAL OUTLINE - 2006 13. Civil Supplies (i) Fair Price Shops 13 (ii) Ration Cards Holder(APL+Temp) 4317 (iii) Quantity of Rice Allotted (MT) 283000 (iv) Quantity of Sugar Allotted (MT) 24000 (v) Quantity of Wheat Allotted (MT) -- 14. Education (a) Institutions (i) Primary School 6 (ii) Middle School 3 (iii) Secondary School 4 (iv) Senior Secondary School 4 (b) Enrollment (i) Primary School 183 (ii) Middle School 647 (iii) Secondary School 632 (iv) Senior Secondary School 1842 (c) Teaching staff (i) Primary School 23 (ii) Middle School 32 (iii) Secondary School 47 (iv) Senior Secondary School 49 15. -

Imperializing Norden

Neumann, Iver B. Imperializing Norden Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Neumann, Iver B. (2014) Imperializing Norden. Cooperation and Conflict, 49 (1). pp. 119-129. ISSN 0010-8367 DOI: 10.1177/0010836714520745 © 2014 by Nordic International Studies Association, SAGE Publications This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56565/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Imperializing Norden.1 Cooperation and Conflict 49 (1): 119-129 (2014) Epilogue for a special issue on Post-Imperial Sovereignty Games in Norden Iver B. Neumann, [email protected] Abstract The two pre-Napoleonic Nordic polities are best understood as empires. Drawing on recent analytical and historical scholarship on empires, I argue that 17th and 18th-century Denmark, on which the piece concentrates, was very much akin to other European empires that existed at the time. -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

Andaman & Nicobar Islands Pondicherry. Census Atlas, Part-XII

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-36 &35 PART-XII ANDAMANAND NICOBAR ISLANDS & PONDICHERRY CENSUS ATLAS Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India FOREWARD Census ofIndia, is perhaps, one of the largest castes and scheduled tribes, education and producer of maps in the country and in each census housing characteristics of the StatelUnion territory. decade nearly 10,000 maps of different categories The unit of the presentation of data is district/sub and themes are published. Earlier to 1961 Census, district. The adoption of GIS technique has not the maps were published in the census reports/tables only made this work more comprehensive but has as supporting documents. During Census 1961, a helped improve the quality of Census Atlas 200 I of new series of 'Census Atlas of States and Union State and Union territories. territories' was introduced which has been continued in the subsequent censuses. The maps have been prepared mostly by choropleth technique but other cartographic Census Atlas of States and Union territories methodologies, such as bar and sphere diagrams, 2001 are based on census data covering different pyramids, isotherms and isohyets have also been themes. Broadly, there are one hundred and adopted to prepare the maps as per the suitability twenty three themes proposed to be included in the and requirement of data. StatelUnion territory Census Atlas. But the number ns well its presentation varies from State to This project has been completed by the State depending upon the availability of data. The respective Directorates under the technical maps included in the publication are divided into supervision of Shri C. -

Moving Forward EU-India Relations. the Significance of the Security

Moving Forward EU-India Relations The Significance of the Security Dialogues edited by Nicola Casarini, Stefania Benaglia and Sameer Patil Edizioni Nuova Cultura Output of the project “Moving Forward the EU-India Security Dialogue: Traditional and Emerging Issues” led by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in partnership with Gate- way House: Indian Council on Global Relations (GH). The project is part of the EU-India Think Tank Twinning Initiative funded by the European Union. First published 2017 by Edizioni Nuova Cultura for Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 – I-00186 Rome – Italy www.iai.it and Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations Colaba, Mumbai – 400 005 India Cecil Court, 3rd floor Copyright © 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations (ch. 2-3, 6-7) and Istituto Affari Internazionali (ch. 1, 4-5, 8-9) ISBN: 9788868128531 Cover: by Luca Mozzicarelli Graphic composition: by Luca Mozzicarelli The unauthorized reproduction of this book, even partial, carried out by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or didactic use, is prohibited by copyright. Table of Contents Abstracts .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 15 1. Maritime Security and Freedom of Navigation from the South China Sea and Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: -

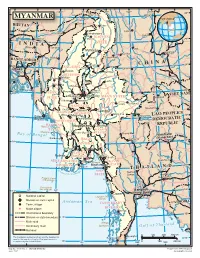

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Cadet's Hand Book (Navy)

1 CADET’S HAND BOOK (NAVY) SPECIALISED SUBJECT 2 Preface 1. National Cadet Corps (NCC), came into existence, on 15 July 1948 under an Act of Parliament. Over the years, NCC has spread its activities and values, across the length and breadth of the country; in schools and colleges, in almost all the districts of India. It has attracted millions of young boys and girls, to the very ethos espoused by its motto, “unity and discipline” and molded them into disciplined and responsible citizens of the country. NCC has attained an enviable brand value for itself, in the Young India’s mind space. 2. National Cadet Corps (NCC), aims at character building and leadership, in all walks of life and promotes the spirit of patriotism and National Integration amongst the youth of the country. Towards this end, it runs a multifaceted training; varied in content, style and processes, with added emphasis on practical training, outdoor training and training as a community. 3. With the dawn of Third Millennia, there have been rapid strides in technology, information, social and economic fields, bringing in a paradigm shift in learning field too; NCC being no exception. A need was felt to change with times. NCC has introduced its New Training Philosophy, catering to all the new changes and developments, taking place in the Indian Society. It has streamlined and completely overhauled its training philosophy, objectives, syllabus, methodology etc, thus making it in sync with times. Subjects like National Integration, Personality Development and Life Skills, Social Service and Community Development activities etc, have been given prominent thrust.