FURTHER EXPERIMENTS on the CONTROL of BARLEY SMUTS by R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes

Ustilago: Habitat, Symptoms and Reproduction | Teliomycetes For B.Sc. Botany 1st By Dr. Meenu Gupta Assistant Professor Botany J.D.W.C. Patna 1. Habit and Habitat of Ustilago: Ustilago, the largest genus of the family Ustilaginaceae is represented by more than 400 cosmopolitan species. Butler and Bisby (1958) reported 108 species from India. All species are parasitic and infect the floral parts of wheat, barley, oat, maize, sugarcane, Bajra, rye and wild grasses. The name Ustilago has been derived from a Latin word ustus meaning ‘burnt’ because the members of the genus produce black, sooty powdery mass of spores on the host plant parts imparting them a ‘burnt’ appearance. This black dusty mass of spores resembles soot or smut, therefore, commonly it is also known as smut fungus. The fungus is of much economic importance, because it causes heavy loss to various economically important plants. This genus is very common in U.P., Bihar, Punjab and Madhya Pradesh. 2. Symptoms of Ustilago: The symptoms appear only on the floral parts. The floral spikes turn black and remain filled with the smut spores. Ustilago produces two main types of symptoms: 1. The blackish powder of spores is easily blown away by the wind, leaving a bare stalk of inflorescence (Fig. 1 B). Species showing such symptoms are called loose smuts e.g., (a) Loose smut of oat caused by U. avenae (b) Loose smut of barley caused by U. nuda (c) Loose smut of wheat caused by U. nuda var. tritici. (Fig. 13A, B). (d) Loose smut of doob grass caused by U. -

The Ustilaginales (Smut Fungi) of Ohio*

THE USTILAGINALES (SMUT FUNGI) OF OHIO* C. W. ELLETT Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, The Ohio State University, Columbus 10 The smut fungi are in the order Ustilaginales with one family, the Ustilaginaceae, recognized. They are all plant parasites. In recent monographs 276 species in 22 genera are reported in North America and more than 1000 species have been reported from the world (Fischer, 1953; Zundel, 1953; Fischer and Holton, 1957). More than one half of the known smut fungi are pathogens of species in the Gramineae. Most of the smut fungi are recognized by the black or brown spore masses or sori forming in the inflorescences, the leaves, or the stems of their hosts. The sori may involve the entire inflorescence as Ustilago nuda on Hordeum vulgare (fig. 2) and U. residua on Danthonia spicata (fig. 7). Tilletia foetida, the cause of bunt of wheat in Ohio, sporulates in the ovularies only and Ustilago violacea which has been found in Ohio on Silene sp. forms spores only in the anthers of its host. The sori of Schizonella melanogramma on Carex (fig. 5) and of Urocystis anemones on Hepatica (fig. 4) are found in leaves. Ustilago striiformis (fig. 6) which causes stripe smut of many grasses has sori which are mostly in the leaves. Ustilago parlatorei, found in Ohio on Rumex (fig. 3), forms sori in stems, and in petioles and midveins of the leaves. In a few smut fungi the spore masses are not conspicuous but remain buried in the host tissues. Most of the species in the genera Entyloma and Doassansia are of this type. -

Four Master Teachers Who Fostered American Turn-Of-The-(20<Sup>TH

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2021 January–March 2021—Volume 136, pp. 1–58 https://doi.org/10.5248/136.1 Four master teachers who fostered American turn-of-the-(20TH)-century mycology and plant pathology Ronald H. Petersen Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37919-1100 Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—The Morrill Act of 1862 afforded the US states the opportunity to found state colleges with agriculture as part of their mission—the so-called “land-grant colleges.” The Hatch Act of 1887 gave the same opportunity for agricultural experiment stations as functions of the land-grant colleges, and the “third Morrill Act” (the Smith-Lever Act) of 1914 added an extension dimension to the experiment stations. Overall, the end of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th was a time for growing appreciation for, and growth of institutional education in the natural sciences, especially botany and its specialties, mycology, and phytopathology. This paper outlines a particular genealogy of mycologists and plant pathologists representative of this era. Professor Albert Nelson Prentiss, first of Michigan State then of Cornell, Professor William Russel Dudley of Cornell and Stanford, Professor Mason Blanchard Thomas of Wabash College, and Professor Herbert Hice Whetzel of Cornell Plant Pathology were major players in the scenario. The supporting cast, the students selected, trained, and guided by these men, was legion, a few of whom are briefly traced here. Key words—“New Botany,” European influence, agrarian roots Chapter 1. Introduction When Dr. Lexemual R. -

Corn Smuts, RPD No

report on RPD No. 203 PLANT February 1990 DEPARTMENT OF CROP SCIENCES DISEASE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CORN SMUTS Corn smuts occur throughout the world. Common corn smut, caused by the fungus Ustilago zeae (synonym U. maydis), and head smut, caused by the fungus Sporisorium holci-sorghi (synonyms Sphacelotheca reiliana, Sorosporium reilianum and Sporisorium reilianum), are spectacular in appearance and easily distinguished. Common smut occurs worldwide wherever corn (maize) is grown, by presence of large conspicuous galls or replacement of grain kernels with smut sori. The quality of the remaining yield is often reduced by the presence of black smut spores on the surface of healthy kernels. COMMON SMUT Common smut is well known to all Illinois growers. The fungus attacks only corn–field corn (dent and flint), Indian or ornamental corn, popcorn, and sweet corn–and the closely related teosinte (Zea mays subsp. mexicana) but is most destructive to sweet corn. The smut is most prevalent on young, actively growing plants that have Figure 1. Infection of common corn smut been injured by detasseling in seed fields, hail, blowing soil or and on the ear. Smut galls are covered by the particles, insects, “buggy-whipping”, and by cultivation or spraying silvery white membrane. equipment. Corn smut differs from other cereal smuts in that any part of the plant above ground may be attacked, from the seedling stage to maturity. Losses from common smut are highly variable and rather difficult to measure, ranging from a trace up to 10 percent or more in localized areas. In rare cases, the loss in a particular field of sweet corn may approach 100 percent. -

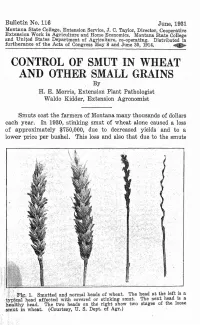

CONTROL of SMUT in WHEAT and OTHER SMALL GRAINS by H

Bulletin No. 116 June, 1931 Montana State College, Extension Service, J. C. Taylor, Director, Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. Montana State College and Uni~ed States Department of Agriculture, co-operating. Distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress ~ay 8 and June 30, 1.914. ~ CONTROL OF SMUT IN WHEAT AND OTHER SMALL GRAINS By H. E. Morris, Extension Plant Pathologist Waldo Kidder, Extension Agronomist Smuts cost the farmers of Montana many thousands of dollars each year. In 1930, stinking smut of wheat alone caused a loss of approximately $750;000, due to decreased yields and to a lower price per bushel. This loss and also that due to the smuts {..:Fig. 1. Smutted and normal heads of wheat. The head at the left ,is a typi:cal head affected with covered or stinking smut, The next, head IS a he'althy head. The two heads on the right show two stages of the loose smut in wheat. (-Courtesy,D. S. Dept. of Agr.) . ,( 2 MONTANA EXTENSION SERVICE of oats, barley and rye may be largely prevented by adopting the methods of seed treatment described in this bulletin. What Is Smut Smut is produced by a small parasitic plant, mould-like in appearance, belonging to a group called fungi (Fig. 2). Smut lives most of its life within and at the expense of the wheat plant. The smut powder, so familiar to all, is composed of myriads of spores which correspond to seeds in the higher plants. In the process of harvesting and threshing, these spores are dis· I Fig'. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Ustilago and Sporisorium Species (Basidiomycota, Ustilaginales) Based on Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) Sequences1

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen 976 Molecular phylogeny of Ustilago and Sporisorium species (Basidiomycota, Ustilaginales) based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences1 Matthias Stoll, Meike Piepenbring, Dominik Begerow, Franz Oberwinkler Abstract: DNA sequence data from the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the nuclear rDNA genes were used to determine a phylogenetic relationship between the graminicolous smut genera Ustilago and Sporisorium (Ustilaginales). Fifty-three members of both genera were analysed together with three related outgroup genera. Neighbor-joining and Bayesian inferences of phylogeny indicate the monophyly of a bipartite genus Sporisorium and the monophyly of a core Ustilago clade. Both methods confirm the recently published nomenclatural change of the cane smut Ustilago scitaminea to Sporisorium scitamineum and indicate a putative connection between Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium. Overall, the three clades resolved in our analyses are only weakly supported by morphological char- acters. Still, their preferences to parasitize certain subfamilies of Poaceae could be used to corroborate our results: all members of both Sporisorium groups occur exclusively on the grass subfamily Panicoideae. The core Ustilago group mainly infects the subfamilies Pooideae or Chloridoideae. Key words: basidiomycete systematics, ITS, molecular phylogeny, Bayesian analysis, Ustilaginomycetes, smut fungi. Résumé : Afin de déterminer la relation phylogénétique des genres Ustilago et Sporisorium (Ustilaginales), responsa- bles du charbon chez les graminées, les auteurs ont utilisé les données de séquence de la région espaceur transcrit interne (ITS) des gènes nucléiques ADNr. Ils ont analysé 53 membres de ces genres, ainsi que trois genres apparentés. Les liens avec les voisins et l’inférence bayésienne de la phylogénie indiquent la monophylie d’un genre Sporisorium bipartite et la monophylie d’un clade Ustilago central. -

<I>Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces</I>

Persoonia 29, 2012: 55–62 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj REVIEW ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/003158512X660283 A review of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex A.R. McTaggart1,2,3,5, R.G. Shivas1,2, A.D.W. Geering1,2,5, K. Vánky4, T. Scharaschkin1,3 Key words Abstract The fungal genera Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces represent an unresolved complex. Taxa within the complex often possess characters that occur in more than one genus, creating uncertainty for species smut fungi placement. Previous studies have indicated that the genera cannot be separated based on morphology alone. systematics Here we chronologically review the history of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex, argue for its Ustilaginaceae resolution and suggest methods to accomplish a stable taxonomy. A combined molecular and morphological ap- proach is required to identify synapomorphic characters that underpin a new classification. Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces require explicit re-description and new genera, based on monophyletic groups, are needed to accommodate taxa that no longer fit the emended descriptions. A resolved classification will end the taxonomic confusion that surrounds generic placement of these smut fungi. Article info Received: 18 May 2012; Accepted: 3 October 2012; Published: 27 November 2012. INTRODUCTION TAXONOMIC HISTORY Three genera of smut fungi (Ustilaginomycotina), Ustilago, Ustilago Spo ri sorium and Macalpinomyces, contain about 540 described Ustilago, derived from the Latin ustilare (to burn), was named species (Vánky 2011b). These three genera belong to the by Persoon (1801) for the blackened appearance of the inflores- family Ustilaginaceae, which mostly infect grasses (Begerow cence in infected plants, as seen in the type species U. -

The History, Fungal Biodiversity, Conservation, and Future Volume 1 · No

IMA FungUs · vOlume 1 · no 2: 123–142 The history, fungal biodiversity, conservation, and future ARTICLE perspectives for mycology in Egypt Ahmed M. Abdel-Azeem Botany Department, Faculty of Science, University of Suez Canal, Ismailia 41522, Egypt; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Records of Egyptian fungi, including lichenized fungi, are scattered through a wide array Key words: of journals, books, and dissertations, but preliminary annotated checklists and compilations are not checklist all readily available. This review documents the known available sources and compiles data for more distribution than 197 years of Egyptian mycology. Species richness is analysed numerically with respect to the fungal diversity systematic position and ecology. Values of relative species richness of different systematic and lichens ecological groups in Egypt compared to values of the same groups worldwide, show that our knowledge mycobiota of Egyptian fungi is fragmentary, especially for certain systematic and ecological groups such as species numbers Agaricales, Glomeromycota, and lichenized, nematode-trapping, entomopathogenic, marine, aquatic and coprophilous fungi, and also yeasts. Certain groups have never been studied in Egypt, such as Trichomycetes and black yeasts. By screening available sources of information, it was possible to delineate 2281 taxa belonging to 755 genera of fungi, including 57 myxomycete species as known from Egypt. Only 105 taxa new to science have been described from Egypt, one belonging to Chytridiomycota, 47 to Ascomycota, 55 to anamorphic fungi and one to Basidiomycota. Article info: Submitted: 10 August 2010; Accepted: 30 October 2010; Published: 10 November 2010. INTRODUCTION which is currently accepted as a working figure although recognized as conservative (Hawksworth 2001). -

Archaeobotanical Evidence of the Fungus Covered Smut (Ustilago Hordei) in Jordan and Egypt

ANALECTA Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwen- huyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. Meijer, Luc Amkreutz, Bertil van Os, Liesbeth Theunissen, David R. Fontijn, Patrick Valentijn, Richard Jansen, Simone A.M. Lemmers, David R. Fontijn, Sasja A. van der Vaart, Harry Fokkens, Corrie Bakels, L. Bouke van der Meer, Clasina J.G. van Doorn, Reinder Neef, Federica Fantone, René T.J. Cappers, Jasper de Bruin, Eric M. Moormann, Paul G.P. PRAEHISTORICA Meyboom, Lisa C. Götz, Léon J. Coret, Natascha Sojc, Stijn van As, Richard Jansen, Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen, Menno L.P. Hoogland, Corinne L. Hofman, Alexander Geurds, Laura N.K. van Broekhoven, Arie Boomert, John Bintliff, Sjoerd van der Linde, Monique van den Dries, Willem J.H. Willems, Thijs van Kolfschoten, Wil Roebroeks, Dimitri De Loecker, Michael H. Field, Pál Sümegi, Kay C.J. Beets, Simon R. Troelstra, Alexander Verpoorte, Bleda S. Düring, Eva Visser, Sophie Tews, Sofia Taipale, Corijanne Slappendel, Esther Rogmans, Andrea Raat, Olivier Nieuwenhuyse, Anna Meens, Lennart Kruijer, Harmen Huigens, Neeke Hammers, Merel Brüning, Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Pieter van de Velde, Hans van der Plicht, Annelou van Gijn, Miranda de Kreek, Eric Dullaart, Joanne Mol, Hans Kamermans, Walter Laan, Milco Wansleeben, Alexander Verpoorte, Ilona Bausch, Diederik J.W. -

Corn Smuts S

A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication Oregon State University • University of Idaho • Washington State University PNW 647 • July 2013 Corn Smuts S. K. Mohan, P. B. Hamm, G. H. Clough, and L. J. du Toit orn smuts are widely distributed throughout the world. The incidence of corn smuts in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) varies Cby location and is usually low. Nonetheless, these diseases occasionally cause significant economic losses when susceptible cultivars are grown under conditions favorable for disease development. Smut diseases of corn are, in general, more destructive to sweet corn than to field corn. The term smut is derived from the powdery, dark brown to black, soot-like mass of spores produced in galls. These galls can form on various plant parts. Three types of smut infect corn—common smut, caused by Ustilago maydis (= Ustilago zeae); head smut, caused by Sphacelotheca reiliana; and false smut, caused by Ustilaginoidea virens. False smut is not a concern in the PNW, so this publication deals University S. Krishna by State Mohan,Photo © Oregon only with common and head smuts. Figure 1. Common smut galls on an ear of sweet corn. Each gall represents a single kernel infected by the common Common smut smut fungus. Common smut is caused by the fungal pathogen U. maydis and is also known as boil smut or blister smut (Figure 1). Common smut occurs throughout PNW corn production areas, although it is less common in western Oregon and western Washington than east of the Cascade Mountains. Infection in commercial plantings may result in considerable damage and yield loss in some older sweet corn cultivars, but yield loss in some of the newer, less susceptible cultivars is rarely significant. -

Color Plates

Color Plates Plate 1 (a) Lethal Yellowing on Coconut Palm caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen. (b, c) Tulip Break on Tulip caused by Lily Latent Mosaic Virus. (d, e) Ringspot on Vanda Orchid caused by Vanda Ringspot Virus R.K. Horst, Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook, DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2141-8, 701 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 702 Color Plates Plate 2 (a, b) Rust on Rose caused by Phragmidium mucronatum.(c) Cedar-Apple Rust on Apple caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Color Plates 703 Plate 3 (a) Cedar-Apple Rust on Cedar caused by Gymnosporangium juniperi.(b) Stunt on Chrysanthemum caused by Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid. Var. Dark Pink Orchid Queen 704 Color Plates Plate 4 (a) Green Flowers on Chrysanthemum caused by Aster Yellows Phytoplasma. (b) Phyllody on Hydrangea caused by a Phytoplasma Pathogen Color Plates 705 Plate 5 (a, b) Mosaic on Rose caused by Prunus Necrotic Ringspot Virus. (c) Foliar Symptoms on Chrysanthemum (Variety Bonnie Jean) caused by (clockwise from upper left) Chrysanthemum Chlorotic Mottle Viroid, Healthy Leaf, Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid, Chrysanthemum Stunt Viroid, and Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid (Mild Strain) 706 Color Plates Plate 6 (a) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Dieffenbachia caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi.(b) Bacterial Leaf Rot on Philodendron caused by Erwinia chrysanthemi Color Plates 707 Plate 7 (a) Common Leafspot on Boston Ivy caused by Guignardia bidwellii.(b) Crown Gall on Chrysanthemum caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens 708 Color Plates Plate 8 (a) Ringspot on Tomato Fruit caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus. (b, c) Powdery Mildew on Rose caused by Podosphaera pannosa Color Plates 709 Plate 9 (a) Late Blight on Potato caused by Phytophthora infestans.(b) Powdery Mildew on Begonia caused by Erysiphe cichoracearum.(c) Mosaic on Squash caused by Cucumber Mosaic Virus 710 Color Plates Plate 10 (a) Dollar Spot on Turf caused by Sclerotinia homeocarpa.(b) Copper Injury on Rose caused by sprays containing Copper. -

Common Diseases of Small Grains and Their Management

Common Diseases of Small Grains and Their Management Gary C. Bergstrom Cornell University Section of Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Central New York Small Grains Workshop February 3, 2015 West Winfield, NY Plant Disease: A condition of a plant of abnormal growth or function Plant Pathogen: A living organism that can incite plant disease Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University When a microbe feeds on a: It is called a: Living host parasite Non-living host saprophyte When a pathogen: It is called a: Gets its nutrients from biotroph living cells Kills host cells before necrotroph acquiring nutrients Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Causal agents (pathogens) of infectious plant diseases • FUNGUS • OOMYCETE • BACTERIUM • VIRUS • NEMATODE Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Factors affecting disease epidemiology and management • Pathogen dissemination potential – (long-distance, regional, local) • Survival in debris • Vector relationship • Favorable environment Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Methods of disease management • Cultural (e.g., crop rotation) • Resistance (e.g., resistant or tolerant varieties) • Biological (e.g., biopesticides) • Chemical (e.g., fungicide seed treatment) • Regulatory (e.g., seed certification) Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Yellow dwarf of cereals and grasses Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Yellow dwarf of cereals and grasses • Pathogen: Barley yellow dwarf luteovirus and Cereal yellow dwarf polerovirus strains • Host range: all grasses • Symptoms: leaves yellow to red or purple; stunting • Conditions: early planting; large aphid populations • Survival: in infected aphids and grasses • Spread: by aphids (short & long distance) • Management:plant after Hessian fly free date, systemic seed insecticides Gary C. Bergstrom, Cornell University Soilborne viruses © G.C. Bergstrom Gary C.