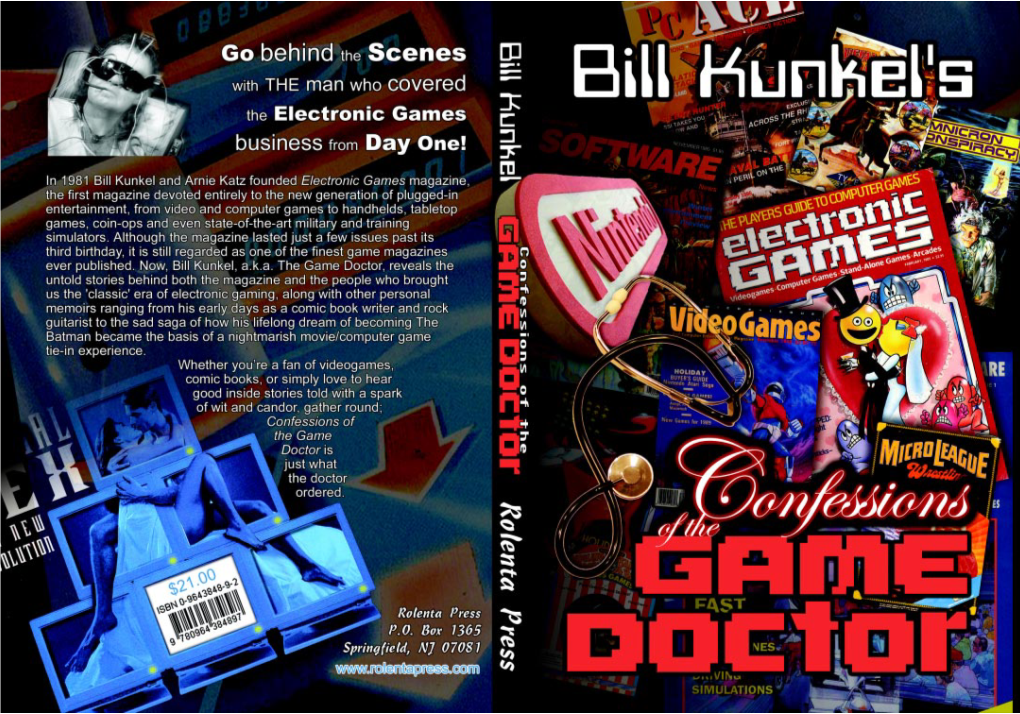

Confessions of Game Doctor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Gooding, P. and Terras, M. (2008) "„Grand Theft Archive‟: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation". The International Journal of Digital Curation. Issue 2, Volume 3, 2008. http://www.ijdc.net/ijdc/article/view/85/90 1 ‘Grand Theft Archive’: A Quantitative Analysis of the Current State of Computer Game Preservation Paul Gooding, Librarian, BBC Sports Library, London Melissa Terras, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London November 2008 Abstract Computer games, like other digital media, are extremely vulnerable to long-term loss, yet little work has been done to preserve them. As a result we are experiencing large-scale loss of the early years of gaming history. Computer games are an important part of modern popular culture, and yet are afforded little of the respect bestowed upon established media such as books, film, television and music. We must understand the reasons for the current lack of computer game preservation in order to devise strategies for the future. Computer game history is a difficult area to work in, because it is impossible to know what has been lost already, and early records are often incomplete. This paper uses the information that is available to analyse the current status of computer game preservation, specifically in the UK. It makes a quantitative analysis of the preservation status of computer games, and finds that games are already in a vulnerable state. It proposes that work should be done to compile accurate metadata on computer games and to analyse more closely the exact scale of data loss, while suggesting strategies to overcome the barriers that currently exist. -

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

The International Game Journalists Association and Games Press Present THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL DAVID THOMAS KYLE ORLAND SCOTT STEINBERG EDITED BY SCOTT JONES AND SHANA HERTZ THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL All Rights Reserved © 2007 by Power Play Publishing—ISBN 978-1-4303-1305-2 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer The authors of this book have made every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the guide. Due to the nature of this work, editorial decisions about proper usage may not reflect specific business or legal uses. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible to any person or entity with respects to any loss or damages arising from use of this manuscript. FOR WORK-RELATED DISCUSSION, OR TO CONTRIBUTE TO FUTURE STYLE GUIDE UPDATES: WWW.IGJA.ORG TO INSTANTLY REACH 22,000+ GAME JOURNALISTS, OR CUSTOM ONLINE PRESSROOMS: WWW.GAMESPRESS.COM TO ORDER ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL PLEASE VISIT: WWW.GAMESTYLEGUIDE.COM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks go out to the following people, without whom this book would not be possible: Matteo Bittanti, Brian Crecente, Mia Consalvo, John Davison, Libe Goad, Marc Saltzman, and Dean Takahashi for editorial review and input. Dan Hsu for the foreword. James Brightman for his support. Meghan Gallery for the front cover design. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 in the USA

Roy Thomas’Star-Crossed LORDIE, LORDIE! Comics Fanzine “THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 In the USA 40!40! No.145 March 2017 WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR BE CAREFUL YOU DON’T WIND UP WITH WARS NOW! 100 PAGES IN FULL COLOR! 1 82658 00092 9 "MAKIN' WOOKIEE" with CHAYKIN & THOMAS Vol. 3, No. 145 / March 2017 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Contents Proofreaders Writer/Editorial: Star Wars—The Comic Book—Turns 40! . 2 Rob Smentek Makin’ Wookiee. 3 William J. Dowlding Roy Thomas tells Richard Arndt about the origins and pitfalls of Marvel’s 1977 Star Wars Cover Artist comic. Howard Chaykin Howard Chaykin On Star Wars . 54 Cover Colorist The artist/co-adapter of Star Wars #1-10 takes a brief look backward. Unknown Rick Hoberg On Star Wars . 58 With Special Thanks to: From helping pencil Star Wars #6—to a career at Lucasfilm. Rob Allen Jim Kealy Heidi Amash Paul King Bill Wray On Star Wars. 63 Pedro Angosto Todd Klein Rick Hoberg dragged him into inking Star Wars #6—and Bill’s glad he did! Richard J. Arndt Michael Kogge Rodrigo Baeza Paul Kupperberg The 1978 Star Wars Comic Adaptation . 67 Bob Bailey Vicki Crites Lane Lee Harsfeld takes us on a tour of veteran comics artist Charles Nicholas’ version of Mike W. -

Gamasutra - Features - the History of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM

Gamasutra - Features - The History Of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM The History Of Activision By Jeffrey Fleming The Memo When David Crane joined Atari in 1977, the company was maturing from a feisty Silicon Valley start-up to a mass-market entertainment company. “Nolan Bushnell had recently sold to Warner but he was still around offering creative guidance. Most of the drug culture was a thing of the past and the days of hot-tubbing in the office were over,” Crane recalled. The sale to Warner Communications had given Atari the much-needed financial stability required to push into the home market with its new VCS console. Despite an uncertain start, the VCS soon became a retail sensation, bringing in hundreds of millions in profits for Atari. “It was a great place to work because we were creating cutting-edge home video games, and helping to define a new industry,” Crane remembered. “But it wasn’t all roses as the California culture of creativity was being pushed out in favor of traditional corporate structure,” Crane noted. Bushnell clashed with Warner’s board of directors and in 1978 he was forced out of the company that he had founded. To replace Bushnell, Warner installed former Burlington executive Ray Kassar as the company’s new CEO, a man who had little in common with the creative programmers at Atari. “In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit sharing and other bonuses. Unfortunately, when it came time to distribute these windfalls, senior management denied ever making such promises,” Crane remembered. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

A Page 1 CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Atari Text

A CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY 3D Tic-Tac Toe Atari Text 2 3D Tic-Tac Toe Sears Text 3 Action Pak Atari 6 Adventure Sears Text 3 Adventure Sears Picture 4 Adventures of Tron INTV White 3 Adventures of Tron M Network Black 3 Air Raid MenAvision 10 Air Raiders INTV White 3 Air Raiders M Network Black 2 Air Wolf Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Air-Sea Battle Atari Text #02 3 Air-Sea Battle Atari Picture 2 Airlock Data Age Standard 3 Alien 20th Century Fox Standard 4 Alien Xante 10 Alpha Beam with Ernie Atari Children's 4 Arcade Golf Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Picture 3 Armor Ambush INTV White 4 Armor Ambush M Network Black 3 Artillery Duel Xonox Standard 5 Artillery Duel/Chuck Norris Superkicks Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Ghost Master Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Spike's Peak Xonox Double Ender 6 Assault Bomb Standard 9 Asterix Atari 10 Asteroids Atari Silver 3 Asteroids Sears Text “66 Games” 2 Asteroids Sears Picture 2 Astro War Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Astroblast Telegames Silver 3 Atari Video Cube Atari Silver 7 Atlantis Imagic Text 2 Atlantis Imagic Picture – Day Scene 2 Atlantis Imagic Blue 4 Atlantis II Imagic Picture – Night Scene 10 Page 1 B CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Bachelor Party Mystique Standard 5 Bachelor Party/Gigolo Playaround Standard 5 Bachelorette Party/Burning Desire Playaround Standard 5 Back to School Pak Atari 6 Backgammon Atari Text 2 Backgammon Sears Text 3 Bank Heist 20th Century Fox Standard 5 Barnstorming Activision Standard 2 Baseball Sears Text 49-75108 -

Exploring Ghost Worlds: a Review of the Daniel Clowes Reader

Johnston, P 2013 Exploring Ghost Worlds: A Review of The Daniel Clowes THE COMICS GRID Reader. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 3(1): 7, pp. 1-5, Journal of comics scholarship DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/cg.ag REVIEW Exploring Ghost Worlds: A Review of The Daniel Clowes Reader The Daniel Clowes Reader, Ken Parille, Softcover: 360 pages, Colour and black & white, Fantagraphics, 2013, ISBN: 9781606995891 Paddy Johnston* Daniel Clowes is undoubtedly one of the most influen- tial and prolific cartoonists working today, with a career spanning many decades. The Daniel Clowes Reader (Parille 2013) comes at the perfect time – when interest in Clowes from scholars and critics is at a high, but in which he is still perhaps given less critical attention than his peers Chris Ware, Art Spiegelman, and Marjane Satrapi, all of whom are cited twice as often as Clowes despite his large canon of significant works in comics. With recent books being published on Chris Ware by The University Press of Mississippi and the forthcoming Art Spiegelman collec- tion from Drawn and Quarterly, more significant focused, monographic books are emerging in comics and comics criticism, and The Daniel Clowes Reader is a more than wel- come addition to this emergence. Rather than providing an exhaustive chronological ret- rospective, as it would be tempting to do with such a vol- ume, the book is organised into three sections based on distinct areas of discussion which provide thematic arcs: section one explores Girls and Adolescence, focusing on Clowes’ landmark graphic novel Ghost World; section two explores Boys and Post-Adolescence using some of Clowes’ short stories from Eightball; and section three explores the broader and more fluid areas of Comics, Artists and Audiences, including Clowes’ illustrated manifesto, “Mod- ern Cartoonist,” which originally accompanied Eightball #18 as an attached pamphlet in 1997. -

Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow

San Francisco, California August 20-21, 2005 $5.00 Welcome to Classic Gaming Expo 2005 !! ! Wow .... eight years! It's truly amazing to think that we 've been doing this show, and trying to come up with a fresh introduction for this program, for eight years now. Many things have changed over the years - not the least of which has been ourselves. Eight years ago John was a cable splicer for the New York phone company, which was then called NYNEX, and was happily and peacefully married to his wife Beverly who had no idea what she was in for over the next eight years. Today, John's still married to Beverly though not quite as peacefully with the addition of two sons to his family. He's also in a supervisory position with Verizon - the new New York phone company. At the time of our first show, Sean was seven years into a thirteen-year stint with a convenience store he owned in Chicago. He was married to Melissa and they had two daughters. Eight years later, Sean has sold the convenience store and opened a videogame store - something of a life-long dream (or was that a nightmare?) Sean 's family has doubled in size and now consists of fou r daughters. Joe and Liz have probably had the fewest changes in their lives over the years but that's about to change . Joe has been working for a firm that manages and maintains database software for pharmaceutical companies for the past twenty-some years. While there haven 't been any additions to their family, Joe is about to leave his job and pursue his dream of owning his own business - and what would be more appropriate than a videogame store for someone who's life has been devoted to collecting both the games themselves and information about them for at least as many years? Despite these changes in our lives we once again find ourselves gathering to pay tribute to an industry for which our admiration will never change . -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

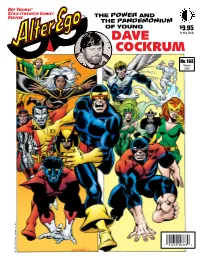

Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: the Red Planet—Mostly in Black-&-White!

Roy Thomas' Xtra-strength Comics Fanzine THE POWER AND THE PANDEMONIUM OF YOUNG $9.95 DAVE In the USA COCKRUM No. 163 March 2020 1 82658 00376 0 Art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 163 / March 2020 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editor Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Don’t STEAL our J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Digital Editions! C’mon citizen, Comic Crypt Editor DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom Michael T. Gilbert & Pop publisher like us needs Editorial Honor Roll every sale just to survive! DON’T Jerry G. Bails (founder) DOWNLOAD Ronn Foss, Biljo White OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com Proofreaders or through our Apple and Google Apps! Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep Cover Artist producing great publications like this one! Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: The Red Planet—Mostly In Black-&-White! .. 2 Glenn Whitmore The Genius of Dave & Paty Cockrum .................. 3 With Special Thanks to: Joe Kramar’s 2003 conversation with one of comics’ most amazing couples. Don Allen David Hajdu Paul Allen Heritage Comics Dave Cockrum—A Model Artist....................... 11 Heidi Amash Auctions Andy Yanchus take a personal look back at his friend’s astonishing model work. Pedro Angosto Tony Isabella “One Of The Most Celebrated Richard Arndt Eric Jansen Bob Bailey Sharon Karibian Comicbook Artists Of Our Time” .................... 15 Mike W. Barr Jim Kealy Paul Allen on corresponding with young Dave Cockrum, ERB fan, in 1969-70. -

Theescapist 071.Pdf

2 a : writing designed for publication in a covered, viewpoint covered, or details So, where does that leave me and my newspaper or magazine b : writing covered, a form of interpretation? research on journalism? Well, I have characterized by a direct presentation of discovered that journalism is a nebulous, facts or description of events without an Designing writing to appeal to taste nuanced beast which cannot be defined Before starting this letter, I sat down to attempt at interpretation c : writing aside, don’t all newspapers and without exceptions, contradictions and find the actual definition of “journalism.” designed to appeal to current popular magazines have some manner of much argument. But, in some attempt to We all have a hand-wavey idea of what it taste or public interest editorial injection of interpretation by discuss journalism further, as it pertains means – likely very close to at least one placement of articles on the cover or on to our beloved Game Industry, we of the definitions listed in any reference The first set smacks of Circular a certain page within, by allocating word present this week’s issue of The Escapist, tool. I looked in many different sources, Definitions. I may have just made up counts per story, etc.? Try as we may to The Rest of the Story. Enjoy! you know, to try to get some sort of this term, but what I mean is a definition report just the facts, we interpret of a consensus. in which the definition leads to another necessity, as there’s limited room for Cheers, word, whose definition leads right back input, both in publications and in our I will give only one set of definitions to the first word.