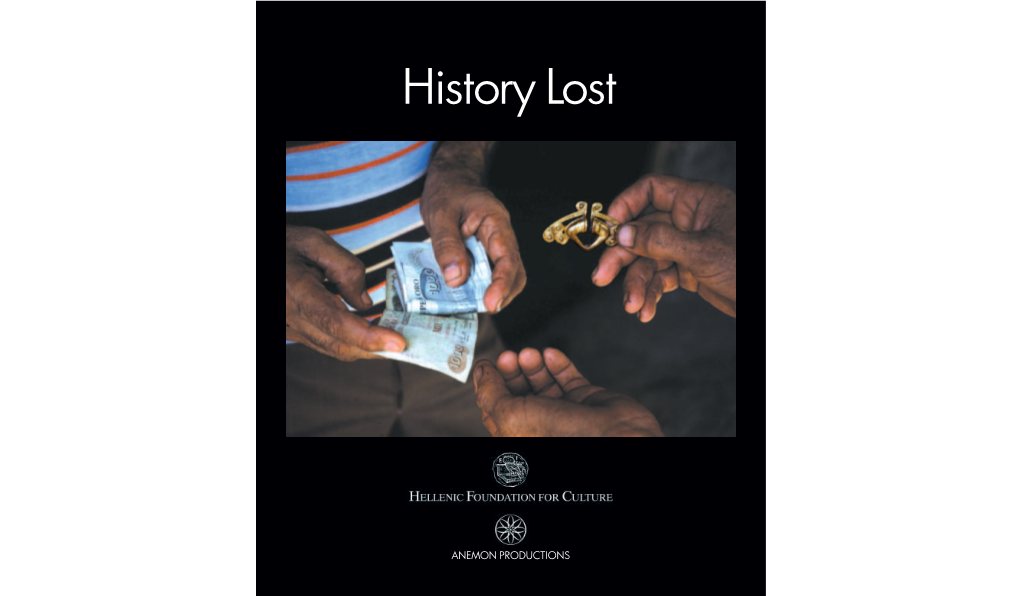

History Lost History Lost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYPRUS Cyprus in Your Heart

CYPRUS Cyprus in your Heart Life is the Journey That You Make It It is often said that life is not only what you are given, but what you make of it. In the beautiful Mediterranean island of Cyprus, its warm inhabitants have truly taken the motto to heart. Whether it’s an elderly man who basks under the shade of a leafy lemon tree passionately playing a game of backgammon with his best friend in the village square, or a mother who busies herself making a range of homemade delicacies for the entire family to enjoy, passion and lust for life are experienced at every turn. And when glimpsing around a hidden corner, you can always expect the unexpected. Colourful orange groves surround stunning ancient ruins, rugged cliffs embrace idyllic calm turquoise waters, and shady pine covered mountains are brought to life with clusters of stone built villages begging to be explored. Amidst the wide diversity of cultural and natural heritage is a burgeoning cosmopolitan life boasting towns where glamorous restaurants sit side by side trendy boutiques, as winding old streets dotted with quaint taverns give way to contemporary galleries or artistic cafes. Sit down to take in all the splendour and you’ll be made to feel right at home as the locals warmly entice you to join their world where every visitor is made to feel like one of their own. 2 Beachside Splendour Meets Countryside Bliss Lovers of the Mediterranean often flock to the island of Aphrodite to catch their breath in a place where time stands still amidst the beauty of nature. -

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

1 Memorandum Ownership Status of Hotels and Other

MEMORANDUM OWNERSHIP STATUS OF HOTELS AND OTHER ACCOMODATION FACILITIES IN THE OCCUPIED PART OF THE REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus hereby publishes a list1 of hotels situated in the Turkish occupied part of Cyprus. The majority of these hotels belong to Greek Cypriot displaced persons who were forced to leave their properties following the Turkish invasion of 1974 or have been built illegally on properties belonging to displaced Greek Cypriots, in violation of the latter’s property rights and without their consent. A number of hotels belong to Turkish Cypriots or have been built on land belonging to Turkish Cypriots. The European Court of Human Rights, in its Judgment of 18 December 1996, on the individual application of the Greek Cypriot displaced owner from Kyrenia, Mrs. Titina Loizidou, against Turkey, and in the Fourth Interstate Application of Cyprus against Turkey of 10 May 2001, upheld the rights of the refugees to their properties. In the Loizidou case, the Court ordered the Government of Turkey to compensate the applicant for the time period of deprivation of use of her property and to provide full access and allow peaceful enjoyment of her property in Kyrenia. The right of the displaced owners to their properties was reconfirmed in the decision of the European Court of Human Rights (Dec. 2005) regarding the application of Myra Xenides- Arestis v. Turkey, and has since been repeatedly reconfirmed in a multitude of cases brought by Greek Cypriot owners of property in the occupied part of Cyprus against Turkey]. It should also be reminded that, according to the United Nations Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons (the Pinheiro principles) “all refugees and displaced persons have the right to have restored to them any housing, land or property of which they were arbitrarily or unlawfully deprived..”. -

Cyprus Island of Saints

NHSOS KYPROS-Engl.-dec2015:Layout 1 12/20/15 11:20 AM Page 1 Monastery of he Office of the Pilgrimage Tours of the Church Timios Stavros, of Cyprus opens its doors like a big Mansion to Church - - - Limit of area under Turkish Omodos Τwelcome the pilgrim and treat him with the holy of Ieron occupation since 1974 Apostolon, gifts of an entire religious world. Inviting him to experience Pera Chorio in the blessed place of the “Island of Saints”, through travels The Five Domed Church of that are real but also noetic, in everliving spiritual Agioi Varnavas and Ilarionas, landscapes, in the most fascinating geography, in Agios Irakleidios, Peristerona from the Church worshipping places that smell incense and from which Scenes of the Second Coming. Church of Archangelos of Panagia spurt spiritual fragrance. Saints and Donors, view of the Michail, Pedoulas tou Araka, The Virgin Narthex, Church of Panagia tis Lagoudera of Kykkou, Asinou Where Archbishop, Bishops, Abbots, Priests, deacons, hermits, Kykkos monks, church wardens and laics, all those who form the Museum body of the Church of Cyprus, with their spiritual work Stavrovouni Monastery lead the human/pilgrim in a “in spirit and truth” worship. “Monasteries bloom on sheer mountains of the island” In Churches, Monasteries, Cloisters, Ecclesiastical Museums Holy Cross in Omodos where a small piece of the rope and Holy Sacristies that gifted many years ago healing to that the soldiers humans. It is not by chance that pilgrims came from afar to used to bind Monastery be cured of their afflictions and seek solace at the shelter of Christ is kept Monastery of Apostle Andreas of Macheras this holyplace island, in the spiritual glow of Christianity’s temperate clime. -

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

A Study of the Role of Intellectuals in the 1931 Uprising

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1999 Intellectuals and Nationalism in Cyprus: A Study of the Role of Intellectuals in the 1931 Uprising Georgios P. Loizides Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Loizides, Georgios P., "Intellectuals and Nationalism in Cyprus: A Study of the Role of Intellectuals in the 1931 Uprising" (1999). Master's Theses. 3885. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3885 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTELLECTUALS AND NATIONALISM IN CYPRUS: A STUDY OF THE ROLE OF INTELLECTUALS IN THE 1931 UPRISING by Georgios P. Loizides A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1999 Copyright by Georgios P. Loizides 1999 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to begin by thanking the members of my Thesis Committee, Dr. Paula Brush (chair), Dr. Douglas Davidson, and Dr. Vyacheslav Karpov for their invaluable help, guidance and insight, before and during the whole thesis-pregnancy period. Secondly, I would like to thank my friends and colleagues at the Department of Sociology for their feedback and support, without which this pro ject would surely be less informed. Georgios P. -

A Description of the Historic Monuments of Cyprus. Studies in the Archaeology and Architecture of the Island

Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028551319 NICOSIA. S. CATHARINE'S CHURCH. A DESCRIPTION OF THE Historic iftlonuments of Cyprus. STUDIES IN THE ARCHEOLOGY AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE ISLAND WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM MEASURED DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS. BT GEORGE JEFFERY, F.S.A., Architect. * * * * CYPRUS: Printed by William James Archer, Government Printer, At the Government Printing Office, Nicosia. 1918. CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. Frontispiece. S. Catharine's Church facing Title . Page Arms of Henry VIII. or England on an Old Cannon . 1 Arms of de L'Isle Adam on an Old Cannon St. Catherine's Church, Nicosia, South Side Plan of Nicosia Town St. Catherine's Church, Nicosia, Plan . „ ,, „ Section Arms of Renier on Palace, Famagusta . Sea Gate and Cidadel, Famagusta Citadel of Famagusta, Elevations ,. Plans Famagusta Fortifications, The Ravelin Ancient Plan of a Ravelin Famagusta Fortifications, Moratto Bastion ,, „ Sea Gate ,, „ St. Luca Bastion St. George the Latin, Famagusta, Section Elevation Plan Plan of Famagusta Gates of Famagusta Church of Theotokos, Galata „ Paraskevi, Galata „ Archangelos, Pedoulas Trikukkia Monastery. Church of Archangelos, Pedoulas Panayia, Tris Elijes Plan of Kyrenia Castle Bellapaise, General Plan . „ Plan of Refectory „ Section of Refectory „ Pulpit in Refectory St. Nicholas, Perapedi Ay. Mavra, Kilani Panayia, Kilani The Fort at Limassol, Plan . SHOET BIBLIOGEAPHY. The Principal Books on Cyprus Archeology and Topography. Amadi, F. Chronicle (1190-1438) Paris, 1891. Bordone, B. Isolario Venice, 1528. Bruyn, C. de, Voyage (1683-1693) London, 1702. -

Euromosaic III Touches Upon Vital Interests of Individuals and Their Living Conditions

Research Centre on Multilingualism at the KU Brussel E U R O M O S A I C III Presence of Regional and Minority Language Groups in the New Member States * * * * * C O N T E N T S Preface INTRODUCTION 1. Methodology 1.1 Data sources 5 1.2 Structure 5 1.3 Inclusion of languages 6 1.4 Working languages and translation 7 2. Regional or Minority Languages in the New Member States 2.1 Linguistic overview 8 2.2 Statistic and language use 9 2.3 Historical and geographical aspects 11 2.4 Statehood and beyond 12 INDIVIDUAL REPORTS Cyprus Country profile and languages 16 Bibliography 28 The Czech Republic Country profile 30 German 37 Polish 44 Romani 51 Slovak 59 Other languages 65 Bibliography 73 Estonia Country profile 79 Russian 88 Other languages 99 Bibliography 108 Hungary Country profile 111 Croatian 127 German 132 Romani 138 Romanian 143 Serbian 148 Slovak 152 Slovenian 156 Other languages 160 Bibliography 164 i Latvia Country profile 167 Belorussian 176 Polish 180 Russian 184 Ukrainian 189 Other languages 193 Bibliography 198 Lithuania Country profile 200 Polish 207 Russian 212 Other languages 217 Bibliography 225 Malta Country profile and linguistic situation 227 Poland Country profile 237 Belorussian 244 German 248 Kashubian 255 Lithuanian 261 Ruthenian/Lemkish 264 Ukrainian 268 Other languages 273 Bibliography 277 Slovakia Country profile 278 German 285 Hungarian 290 Romani 298 Other languages 305 Bibliography 313 Slovenia Country profile 316 Hungarian 323 Italian 328 Romani 334 Other languages 337 Bibliography 339 ii PREFACE i The European Union has been called the “modern Babel”, a statement that bears witness to the multitude of languages and cultures whose number has remarkably increased after the enlargement of the Union in May of 2004. -

A4 ENGLISH-Text

CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION yprus may be a small country, but C it’s a large island - the third largest in the Mediterranean. And it’s an island with a big heart - an island that gives its visitors a genuine welcome and treats them as friends. With its spectacular scenery and enviable climate, it’s no wonder that Aphrodite chose the island as her playground, and since then, mere mortals have been discovering this ‘land fit for Gods’ for themselves. Cyprus is an island of beauty and a country of contrasts. Cool, pine-clad mountains are a complete scene-change after golden sun- kissed beaches; tranquil, timeless villages are in striking contrast to modern cosmopolitan towns; luxurious beachside hotels can be exchanged for large areas of natural, unspoilt countryside; yet in Cyprus all distances are easily manageable, mostly on modern roads and highways - with a secondary route or two for the more adventurous. Most important of all, the island offers peace of mind. At a time when holidays Cyprus are clouded by safety consciousness, a feeling of security prevails everywhere since the crime level is so low as to be practically non-existent. 1 1 ew countries can trace the course of their history over 10.000 years, but F in approximately 8.000 B.C. the island of Cyprus was already inhabited and going through its Neolithic Age. Of all the momentous events that were to sweep the country through the next few 2 thousand years, one of the most crucial was the discovery of copper - or Kuprum in Latin - the mineral which took its name from “Kypros”, the Greek name of Cyprus, and generated untold wealth. -

Oi Oi Oi Οέ Oi Oi

208 /. ' J No. 187. The Elementary Education Laws, 1933 to (No. 2) 1937. NOTICE UNDER SECTION 73 (1). It is hereby notified that in exercise of the powers vested in him by section 73 (1) of the Elementary Education Laws, 1933 to (No. 2) 1937, and otherwise, His Excellency the Governor is pleased to direct and hereby directs that the additional tax mentioned in section 65 of the said Laws payable by the Mohammedan taxpayers of the towns and villages mentioned in the Schedule hereto shall be increased by the rate per thousand shown opposite the name of each such town or village to provide the amount required for the payment of loans or annual maintenance of the Moslem Schools of the said towns and villages respectively. THE SCHEDULE. Additional Additional Town or \niiago tax per Town or Village tax per thousand thousand NICOSIA DISTRICT. NaMeh of Morphou : p. ) Akaki lakh of Deyirmenlik : Oi V- Angolemi i| Ayia Kebir \h Avlona oi Bey Keuy 01- Eliophotes (Alihodes) - oi Dhali .. l Ghaziveran 1 Epikho (Aboukhor) Η Koutraphas, Pano 0-1 Hamid Mandrcs 0£ Morphou . Kaimakli, Beuyuk 1 Skilloura oh Kaimaldi, Kuchuk Oi Nahieh of Lefka : (Omorphita) Kalyvakia .. Alevga Kochati Oh Amadhies 2 Louroujina .. 2 Ambelikou Ayios Epiphanios 1 Mathiati 01: Minareli Keuy Ayios Theodhoros (Tillirias) oi 01 Mora Ayios Yeoryios Nicosia town o-i- Elea . Oh Nisou (Dizdar Keuy' Kalo Khorio (Chamli Keuy) 4 Ornithi Karavostasi (Genii Konaghi) 1 Palekythro .. Kokkina Oi· Pera Khorio Korakou Potamia Lefka Yenije Keuy (Pctra tou Linou Dhiyeni) Petra Phlasou «M'eJt of Dagh: Sela'in t'Api Oi Selemani 1 Aradhiou . -

ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 1

ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 1 Cyprus Spiritual And CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION 19 Lemesos Avenue, P.O.Box: 24535, 1390 Lefkosia, Cyprus Cultural Tel: +357 22 69 11 00 Fax: +357 22 33 16 44 Email: [email protected] Journeys www.visitcyprus.com ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 2 Agios Nikolaos Stegis church Agios Ioannis Lampadistis Museum Panagia tou Araka Monastery Monuments of UNESCO Monuments of UNESCO Monuments of UNESCO Solea region Marathasa region Pitsilia region ● Nikitari: Church of Panagia tis ● Kalopanagiotis: Monastery of Agios ● Lagoudera: Monastery of Panagias Asinou (Virgin of Asinou) ● Galata: Ioannis Lampadistis (St. John tou Araka (the Virgin of Araka) Church of Panagia tis Podithou Lampadistis) ● Moutoulas: Church of ● Platanistasa: Holy Cross of (Virgin of Podithou) ● Kakopetria: the Virgin Mary ● Pedoulas: Church Agiasmati ● Pelendri: Church of the Church of Agios Nikolaos tis Stegis of Archangelos Michael (Archangel Holy Cross ● Palaichori: Church of (Saint Nicholas of the Roof) Michael) the Transfiguration of the Saviour LEFKOSIA NICOSIA Peristerona Monastery of Panagia tou Kykkou Kalopanagiotis Panagia LARNAKA Tala yprus, that “ethereal and blessed Emba land” that stands apart, serene and PAFOS sacred with an irresistible fascination, Geroskipou C LEMESOS ourneys LIMASSOL J is a paradise full of natural beauty, history, mem- ories and culture. A most surprising feature is its Byzantine art in Cyprus West Of density of monuments of religious devotion. It is ● ● an island of distinctive aura and charm, where the Peristerona: Church of Saints Barnabas and Hilarion Kalopanagiotis: ● aith whole spectrum of Christianity’s historical and Monastery of Saint John Lampadistis Monastery of the Virgin Mary of Kykkos F ● Panagia ● Tala ● Emba ● Kato Pafos ● Geroskipou cultural development can be seen, from inception AN INTRODUCTION TO A to the present day. -

215 No. 226. the ELECTIONS (HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES and COMMUNAL CHAMBERS) LAWS, 1959 and 1960

215 No. 226. THE ELECTIONS (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND COMMUNAL CHAMBERS) LAWS, 1959 AND 1960. ORDER MADE UNDER SECTION 19(1). In exercise of the powers vested in him by section 19 (1) of the Elections (House of Representatives and Communal Chambers) Laws, 1959 and 1960, His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to make the following Order :— 1. This Order may be cited as the Elections (House of Representatives and Communal Chambers) (Turkish Polling Districts) Order, 1960. 2. For the purpose of holding a poll for the election of Turkish members of the House of Representatives, and for the election of members of the Turkish Communal Chambers, the six Turkish constituencies in Cyprus shall be divided into the polling districts set out in the first column of the Schedule hereto, the names of the towns or villages the area of which comprise such polling district being shown in the second column of the said Schedule opposite thereto. SCHEDULE. The Turkish Constituency of Nicosia. Town or Villages included Polling District in Polling District Nicosia Town Nicosia Town Kutchuk Kaimakli (a) Kutchuk Kaimakli (b) Kaimakli (c) Η amid Mandres (d) Eylenja (e) Palouriotissa Geunycli (a) Geunyeli (b) Kanlikeuy Ortakeuy (a) Ortakeuy (b) Trachonas (c) Ay. Dhometios (d) Engomi Peristerona (a) Peristerona (b) Akaki (c) Dhenia (d) Eliophotes (e) Orounda Skylloura (a) Skylloura (b) Ay. Vassilios (c) Ay. Marina (Skyllouras) '(d) Dhyo Potami Epicho (a) Epicho (b) Bey Keuy (c) Neochorio (d) Palekythro (e) Kythrea Yenidje Keuy (a) Yenidje Keuy (b) Kourou Monastir (c) Kallivakia Kotchati (a) Kotchati (b) Nissou (c) Margi (d) Analiondas (e) Kataliondas Mathiatis Mathiatis Potamia (a) Potamia (b) Dhali (c) Ay.