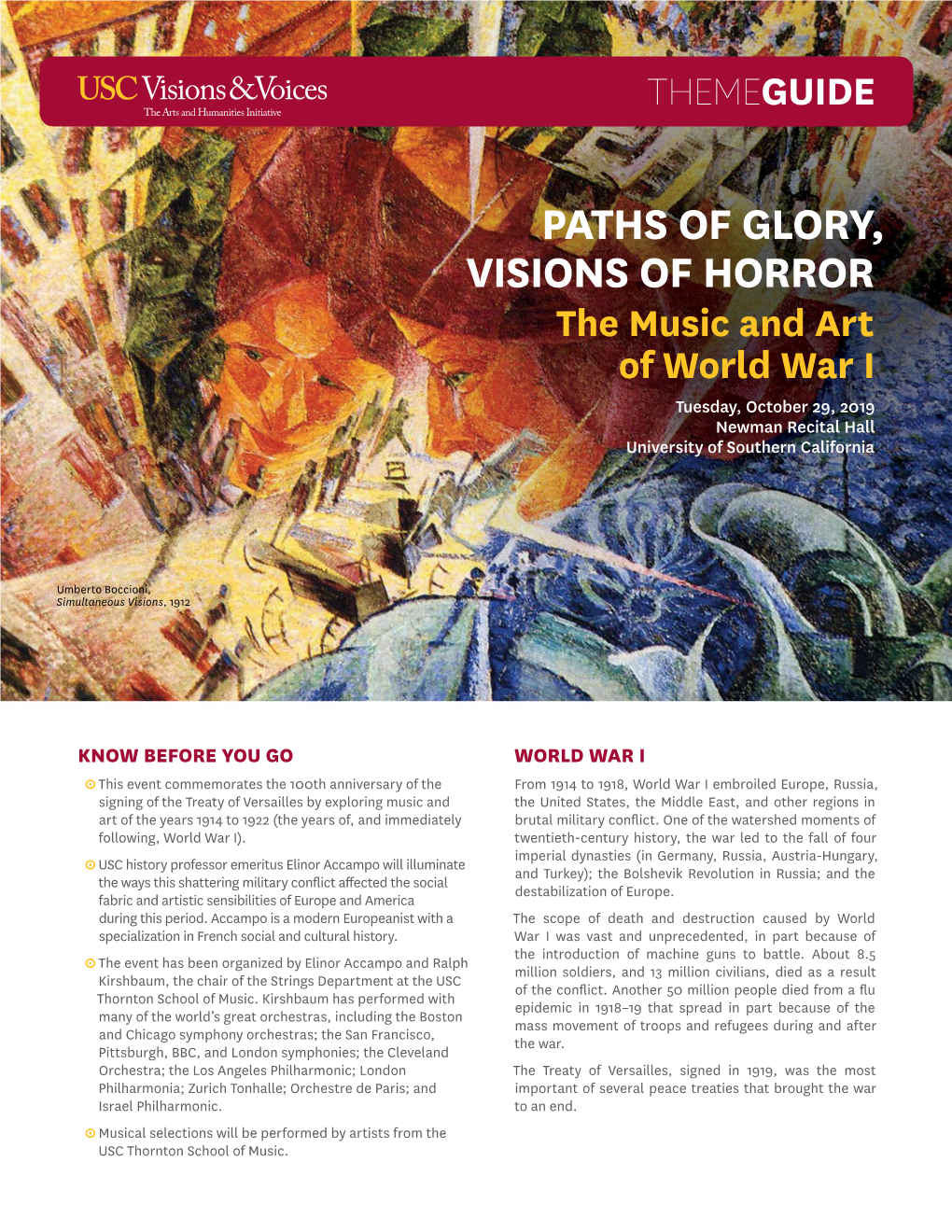

Paths of Glory, Visions of Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ULEMHAS REVIEW 2003 ULEMHAS Review

Birkbeck Continuing Education History of Art Society ULEMHAS REVIEW 2003 ULEMHAS Review EDITORIAL CONTENTS his is the first issue of the ULEMHAS Review in a new Preview of the Late Gothic format, and on an annual rather than a twice-yearly Exhibition - Eleanor Townsend 3 Tbasis. The change has been made for several reasons: it enables us to upgrade production values (although it is not an economy, costing rather more than two photocopied The Battle for Culture: issues); it provides space for items which connect the Review Tradition & Modernism in more closely to ULEMHAS activities and concerns; and it Fascist Italy and Germany gives more time for the gathering of suitable material. It is our aim to continue the tradition of scholarly and - Anna Leung 6 wide-ranging articles that Elizabeth Pillar, Erika Speel and the editorial panel have maintained so effectively over the The Travels of Correggio's previous eighteen issues. We also intend to carry regular previews of important exhibitions and reviews of books of School of Love - Norman Coady 8 interest in the art history field. It may be noted that there is a review in this issue of a Commissioned Visions book by a ULEMHAS member, and others of works by a present and an erstwhile tutor for the Diploma. Some of the - Roger Toison 10 contributors are also members of the Society. We are confident that ULEMHAS is an unexplored repository of Platonic Geometry and the interesting ideas for future issues, and very much hope that you will be inspired to communicate these. Cathedral of Bourges - -

How Was the War Represented?

World War 1 paper 9 How was the war represented? How did the veterans tell the war? The war poets The war poetry of Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg, Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, Edward Thomas and Ivor Gurney among others, marks a transition in English cultural history. These were all young men who, pushed to the limits of experience, found in poetry a means of expressing extreme emotions of fear, anger and love. Their combined voice is more than a personal witness to military events in France from 1914 to 1918. The poems they wrote have become part of the national consciousness, and conscience. They themselves have become icons of innocence, vulnerability, courage and integrity, in a world which after the war felt that these values were increasingly under threat. Owen wrote that: ‘All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true poet must be truthful’. Many of their best poems are driven by a need to communicate the reality of the evils of war, particularly to those back home. At the start of the conflict, poets like Rupert Brooke buoyed the popular enthusiasm for war with rhetoricised feelings of idealism and patriotism. CH Sorley and Robert Graves were among the first to attempt to write in a way which challenged the prevailing spirit by trying to capture the awful reality of the experience. Sassoon, a fellow officer in Graves’s regiment and his closest friend during the war, was at first shocked by Graves’s early realism and thought his poems ‘violent and repulsive’ in both their use of language and their presentation of trench life. -

POISON GAS in WORLD WAR I by Michael Neiberg

June 2012 September 2013 POISON GAS IN WORLD WAR I By Michael Neiberg Michael Neiberg is Professor of History in the Department of National Security Studies at the US Army War College in Carlisle, PA. He has been a Guggenheim fellow, a founding member of the Société Internationale d’Étude de la Grande Guerre, and a trustee of the Society for Military History. His most recent book on the First World War is Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (Harvard University Press, 2011). In October, 2012 Basic Books published his The Blood of Free Men, a history of the liberation of Paris in 1944. In May, 1919, just as the diplomats of the great powers were putting the final touches on what became the Treaty of Versailles, Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts awarded its painting of the year to John Singer Sargent’s “Gassed” (http://jssgallery.org/Paintings/Gassed/Gassed.htm). Sargent, an American, was then 62 years old and already a legend in the art world for his portraits and his epic grand paintings. On the strength of those paintings, he had received a commission from the British government to paint an epic picture for the proposed Hall of Remembrance in London. Unsure of his approach for so crucial a painting, Sargent wrote to a friend to express his concern that he would not be able to find a subject worthy of the grandeur and the scale that the British government wanted for the hall. Sargent had already seen his share of the horrors of the war as an official artist for the American government, yet nothing he had yet seen seemed to him sufficient for the new work. -

Wrs Jan 2012.Qxd

WILLIAM ROBERTS SOCIETY Newsletter, April 2015 Susanna and the Elders c.1926 (detail) – a painting exhibited in WR’s 1965 retrospective – discussed on pages 7–12 – but not since then WRS farewell beano … The William Roberts Society, 1998–2015 … A WR for the BM … A new WR website … WR and the art of the First World War … The 1965 Roberts retrospective … WR on display … Tom Devonshire Jones WILLIAM ROBERTS SOCIETY registered charity no. 1090538 Committee: Pauline Paucker (chairman), Marion Hutton (secretary: Lexden House,Tenby SA70 7BJ; 01834 843295; [email protected]),Arnold Paucker (treasurer), David Cleall (archivist), Bob Davenport (newsletter and website: [email protected]), Michael Mitzman (copyright), Ruth Artmonsky,Anne Goodchild,Agi Katz www.williamrobertssociety.co.uk April 2015 WRS FAREWELL BEANO not so young when we elected our com- mittee are now rather old (Diana Gurney, The a.g.m. on 11 April ratified the com- one of our trustees and a founder mem- mittee’s decision, announced in a letter ber, died recently aged 97), and we all, with last October’s newsletter, that the younger and old, feel that we have society should be wound up. We thank achieved most of our original aims – bar members and friends for their valuable the house museum, so much wished for support over the years; now we look for- by Sarah and John Roberts. ward to raising a final glass together. We initiated the the application for the Please come to a closing-down beano – blue plaque on the Robertses’ house; we a gathering to celebrate the society’s have visited nearly all the holdings of achievements and the friendships forged Roberts’s work within hitting distance of – on Saturday 6 June from 2.30 to 5.00 London; we have led Roberts walks in p.m. -

Research Report | 2018

RESEARCH REPORT | 2018 Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................... 1 1. IWM Institute ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Collaborative Doctoral Partnerships ................................................................................. 4 3. Research Projects .......................................................................................................... 12 4. Publications .................................................................................................................... 15 5. Exhibitions ...................................................................................................................... 21 6. Conferences, lectures and talks ..................................................................................... 25 FOREWORD 2018 started with the sixth Beyond Camps and Forced Labour conference, held at Birkbeck, University of London and the Wiener Library. IWM was one of the founders of this conference and continues to play an active role in its running. A highlight was the keynote by Professor Tim Cole of Bristol University, who spoke about integrating histories and geographies of the Holocaust and Holocaust memory. The creation of the IWM Institute for the Public Understanding of War and Conflict has been a major preoccupation this year, with Research and Academic Partnerships contributing ideas and contacts -

Claire Bowen PAUL NASH

Claire Bowen PAUL NASH AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR OFFICIAL WAR ARTISTS SCHEME Art and the British Propaganda Effort Formal British propaganda activity began within weeks of the declaration of war. By August 1914, Lloyd George had personally asked Charles Masterman, his Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, to look into ways of countering the propaganda campaign already begun by Germany in the U.S.A. By Septem- ber, the Propaganda Department had been established in Wellington House in Central London, under the aegis of the Foreign Office and with Masterman as its Director. It was the first time that such a department had existed in Britain and it was the first war in which all the belligerents came to possess such an institution. The purpose of the Department was to gain the sympathy of influential neutrals and reinforce home support for the war. A good deal of its work, therefore, involved the production and distribution of material presenting the war from the Allied point of view. At this stage the material in question in- cluded articles, write-ups of interviews, photographs, maps, lantern slides, posters, post-cards, etc.—essentially information that lent itself to easy repro- duction by mechanical means and that, generally speaking, echoed the type of didactic entertainment so appreciated by the late Victorians and Edwardians. The Department was staffed by distinguished academics, civil serv- ants, journalists and museum personnel organized into sections dealing with specific activities or targets. From the first, it was clear that the Department was to be the preserve of the intellectuals. This was to be an extremely impor- tant factor in determining the nature of the British propaganda machine. -

Mnemonics for War: Trench Art and The

Mnemonics for War: Trench Art and the 86 | Reconciliation of Public and Private Memory Clare Whittingham, McMaster University The study of British First World War memorials has generated a considerable body of literature since its emergence as a scholarly field in the 1990s. Less attention has been devoted, however, to commemorative objects of a smaller and more personal character that were collected during and after 1914-1918 for display in homes and museums. This paper finds ‘trench art’, battlefield souvenirs and commercially produced war kitsch negotiating the gap between civilian and military experiences of war and its translation into memory. Particular consideration is given to the Imperial War Museum as representative of institutional attitudes towards this unique and still-contested category of unconventionally commemorative material. The study of British First World War memorials has produced a considerable body of literature since its emergence as a subject of scholarly interest in the 1990s.1 Less attention has been paid, however, to the war memorabilia, mementos, battlefield souvenirs and household kitsch now commonly referred to as Trench Art. Though trophies of war were sought by private collectors and public museums well before the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, 1 Modris Eksteins, Jay Winter, Alex King, Adrian Gregory and Catherine Moriarty are some of the many historians who have considered First World War memorials and commemoration practices in recent years. Past Imperfect 14 (2008) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 trench art of the First World War has uniquely resisted institutional classification, challenged conventional curatorial wisdom and seldom been exhibited in public displays. -

Clouded Vision: Art and Exhibition During WWI

Clouded Vision: Art and Exhibition During WWI by Elizabeth Popovic Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to the Department of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Art April, 2021 Jim Toub, Ph.D, Thesis Director Heather Waldroup, Ph.D, Second Reader Heather Waldroup, Ph.D, Interim Departmental Honors Director Popovic 1 Table of Contents I. Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..2 II. Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………....3 III. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..4-8 IV. Popular Mediums of Expression During WWI………………………………………..9-19 V. Propaganda and Memorialization During WWI…………………………..………….20-30 VI. Creation of the British War Memorials Committee and the Imperial War Museum....31-41 VII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………....41-46 VIII. Image Bank………………………………………………………………….…....…..47-54 IX. Works Cited………………………………………………………………………......55-56 Popovic 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Jim Toub, for being such a diligent mentor. He has spent many hours reading through my thesis drafts, meeting with me to discuss them, and giving his thoughtful comments and advice, for which I am thankful. I am also grateful to Dr. Heather Waldroup, who has served as my second reader as well as my mentor and professor throughout a rigorous senior year. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Mira Waits, who has also served as an influential mentor and professor during my time at Appalachian State University. Lastly, I give a warm thank you to my friends and family who have supported me through the highs and lows of the thesis process. Popovic 3 Abstract During the First World War, the first efforts to memorialize the conflict were heavily influenced by the propaganda characteristic of the era. -

'A War of the Imagination'

Paul Gough, „A Terrible Beauty‟, 2010, ISBN-10: 1906593000 This is the opening Chapter of PAUL GOUGH, A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War, Sansom, Bristol, 2010, ISBN-10: 1906593000, and ISBN-13: 978-1906593001 INTRODUCTION Like many other professions caught up in the heady first months of the war, painters and sculptors –professional and amateur, famous and obscure – were called upon to enlist in the armed services. Some thirty artists joined the RAMC en bloc following a single recruitment visit to the bar of the Chelsea Arts Club by the commandant of the 3rd London General Hospital. (1) The Studio – a popular arts and crafts magazine – ran page-long lists of those who had signed up; many joined the Artists‟ Rifles, an officer-training unit, which attracted painters, poets, architects, writers, and many others with artistic aspirations – if not the talent. (2) Some chose to ignore the call to arms. Many had little choice: war was bad for business. The art market shrivelled, prices tumbled, artist‟s materials became scarce. While emerging artists wrestled with their patriotic consciences, established artists were expected to donate items of work to patriotic causes or to offer up blank canvases for auctions organised by the Red Cross and other charities. (3) However, not everyone in Britain thought the onset of war an unmitigated catastrophe. Many on the right of the political spectrum saw it not as the end of the golden period of Victorian and Edwardian eminence, but an opportunity to purge the nation of social maladies – amongst them feminism, industrialization, modernism, and futurism – which they felt had blighted the country in the previous decade. -

Paul Nash Large Print Guide

PAUL NASH 26 October 2016 – 5 March 2017 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to exhibition entrance CONTENTS Introduction Page 1 Room 1 Dreaming Trees Page 3 Room 2 We are Making a New World Page 18 Room 3 Places Page 30 Room 4 Room and Book Page 46 Room 5 Unit One Page 61 Room 6 The Life of The Inanimate Object Page 73 Room 7 Unseen Landscapes Page 122 Room 7a International Surrealist Exhibition Page 133 Room 8 Aerial Creatures Page 156 Room 9 Equinox Page 167 Find out more Page 177 INTRODUCTION 1 Paul Nash (1889–1946) was a key figure in debates about British art’s relationship to international modernism through both his art and his writing. He was involved with some of the most important exhibitions and artistic groupings of the 1930s and was a leading figure in British surrealism. He began his career as an illustrator, influenced by William Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites, and explored symbolist ideas while developing a personal mythology of landscape. In response to the First World War he evolved a powerful symbolic language and his work gained significant public recognition. Much of the 1920s saw Nash processing the memories of war through the landscapes of particular places that had a personal significance for him, while in the 1930s he explored surrealist ideas of the found object and the dream, and expanded the media he worked in to include collage and photography. His final decade was spent pursuing ideas of flight and the mystic significance of the sun and moon through a series of visionary landscapes and aerial flower compositions. -

The Great War As Recorded Through the Fine and Popular Arts

The Great War As Recorded through the Fine and Popular Arts Edited by Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss L I S S F I N E A R T This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition: The Great War As Recorded through the Fine and Popular Arts Morley Gallery Morley College, 61 Westminster Bridge Road, London, SE1 7HT September 5 - October 2, 2014 Organised by: L I S S F I N E A R T With the participation of David Cohen Fine Art The Great War As Recorded through the Fine and Popular Arts Edited by Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss L I S S F I N E A R T René Georges Hermann-Paul (1864-1940) 148 – Août 1914 from Calendrier de la Guerre (1ère année – août 1914-juillet 1915), 1916, Coloured woodcuts, 17 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. (45 x 35cm) each, published by Librarie Lutetia [A. Ciavarri, Directeur] Two soldiers from different units who are preparing to embark for the Front, embrace during a chance encounter on a railway platform. The soldier in blue is decorated with flowers, momentoes from women who have bid him adieu. The first months of the war were by far the most bloody, and these friends may never meet again. (see pages 170-173) A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S We are especially grateful to Ela Piotrowska (Principal), Nick Rampley (Vice-Principal) and Jane Hartwell (Gallery Manager) of Morley College for giving us the opportunity to stage this exhibition, and also the Imperial War Museum for allowing this project to be part of a wider series of IWM-led FirstWorld War Centenary Initiatives. -

Order Stanley Spencer

• Following the First World War art took different directions. One group, the Dadaists, we shall look at next time. They completely rejected everything that had gone before as they saw it as part of a social order that led to the death of millions of people. • The other group were associated with the phrase ‘return to order’ and they saw the war as an appalling episode to be forgotten and wanted to return to the figurative art that predominated before the war. One outstanding figurative artists was Stanley Spencer although he was never going to be anything other than a figurative artist. • Sir Stanley Spencer CBE RA (30 June 1891 – 14 December 1959, died aged 68) was an English painter. Shortly after leaving the Slade School of Art, Spencer became well known for his paintings depicting Biblical scenes occurring as if in Cookham, the small village beside the River Thames where he was born and spent much of his life. Notes Phases of his career and major works: 1. Spencer’s Early Life, 1891 to 1914 1. Head of a Slade Girl, 1909 1 2. Two Girls and a Beehive, 1910, private collection 3. John Donne Arriving in Heaven, 1911, Fitzwilliam Museum 4. Self-Portrait, 1914 5. Apple Gatherers, 1912-13, Tate 6. The Centurion’s Servant, 1914, Tate 1. World War One, 1914 to 1918 1. Travoys Arriving with Wounded, 1919 2. Swan Upping at Cookham, 1915-19, Tate 2. 1920 to 1927, The Resurrection, Cookham 1. The Resurrection, Cookham, 1923 -27, Tate 3. The Sandham Memorial Chapel. Burghclere, 1926-32 (National Trust) 1.