Liability for Sexual Misconduct in the Counseling Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forms of Address for Clergy the Correct Forms of Address for All Orders of the Anglican Ministry Are As Follows

Forms of Address for Clergy The correct forms of address for all Orders of the Anglican Ministry are as follows: Archbishops In the Canadian Anglican Church there are 4 Ecclesiastical Provinces each headed by an Archbishop. All Archbishops are Metropolitans of an Ecclesiastical Province, but Archbishops of their own Diocese. Use "Metropolitan of Ontario" if your business concerns the Ecclesiastical Province, or "Archbishop of [Diocese]" if your business concerns the Diocese. The Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada is also an Archbishop. The Primate is addressed as The Most Reverend Linda Nicholls, Primate, Anglican Church of Canada. 1. Verbal: "Your Grace" or "Archbishop Germond" 2. Letter: Your Grace or Dear Archbishop Germond 3. Envelope: The Most Reverend Anne Germond, Metropolitan of Ontario Archbishop of Algoma Bishops 1. Verbal: "Bishop Asbil" 2. Letter: Dear Bishop Asbil 3. Envelope: The Right Reverend Andrew J. Asbil Bishop of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto there are Area Bishops (four other than the Diocesan); envelopes should be addressed: The Rt. Rev. Riscylla Shaw [for example] Area Bishop of Trent Durham [Area] in the Diocese of Toronto Deans In each Diocese in the Anglican Church of Canada there is one Cathedral and one Dean. 1. Verbal: "Dean Vail" or “Mr. Dean” 2. Letter: Dear Dean Vail or Dear Mr. Dean 3. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto the Dean is also the Rector of the Cathedral. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean and Rector St. James Cathedral Archdeacons Canons 1. Verbal: "Archdeacon Smith" 1. Verbal: "Canon Smith" 2. -

Cathedral Chronicle

For the week of July 25, 2021 CATHEDRAL CHRONICLE 252 James Street North, Hamilton, Ontario L8R 2L3 905-527-1316 ext 240 Emergency on call clergy on call 365-324-4503 wwww.cathedralhamilton.ca WEEKLY PRAYER CYCLE Parish Cycle of Prayer: Tom Zeigler; Helen Wright; Nor- ma Wright. Online Services Anglican Cycle of Prayer: In the world-wide Anglican from the Cathedral Communion we pray for the Scottish Episcopal Church. We invite you to attend the In the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada we pray for following Cathedral services online. The Dean, council, and congregations of the East Central Area of the Synod of Alberta and the Territories. In the Holy Eucharist with Spiritual Communion Anglican Church of Canada we pray for The Right Rever- Sunday after Pentecost, July 25th end Jane Alexander, Bishop, and the clergy and people of To view the service on YouTube click here. the Diocese of Edmonton. In our partner diocese of Cuba The order of service is available on our website, we pray for San Miguel y Todos los Angeles in Ceballos; click here. The Reverend Haydee Marrero Lugo, minister-in-charge and the people of that parish. In our diocese of Niagara we pray for our Bishop, The Right Reverend Susan Bell, St. Aidan, Oakville, The Reverend Fran Wallace, Priest-in -Charge, The Reverend Canon Marni Nancekivell, Honor- Evening Prayer ary Assistant and the people of that parish. Wednesday, July 28th To view the service on YouTube click here. As a community we pray for: Those suffering from psy- The order of service is available on our website, chiatric, emotional and behavioural issues and those who click here. -

His Grace, Bishop Joseph’S Address at the Funeral of the Very Reverend Archpriest Richard Ballew December 16, 2008 Elk Gr

His Grace, Bishop JOSEPH’s Address at the Funeral of the Very Reverend Archpriest Richard Ballew December 16, 2008 Elk Grove, California The beloved Archpriests, Priests and Deacons in Christ; the Family of Father Richard: His wife, Kh. Sylvia; His sister, Betty; His children, Russel, Shelli, Richard, and Randall; His grandchildren; and all of his beloved parishioners and friends who have gathered here to honor Father Richard: In my years as a Bishop, I have presided over many funerals. I have prayed over many a dear friend and many a powerful person. Yet, there are few times where I have done so over someone I would consider to be a historical figure. Today, we pray for the repose of a man I consider being a historical person, a man who has changed the world, a man who has made a difference in his time and place. Father Richard has always been a big man, and not just in terms of is considerable physical presence and Texas mannerisms, but in the work he carried out in behalf of his friends, family and the Church. He was a great man in the sense that he devoted himself whole-heartedly to serving others, a way of life that is becoming more and more rare in our secular world. His true work began when he and his fellows in Campus Crusade for Christ began to realize that there was a gap between their teachings and the reality of the Gospel. Truly, they had to live out our Lord Jesus Christ’s command for mankind to repent in the fullness of humility. -

Cathedral Building in America: a Missionary Cathedral in Utah by the Very Reverend Gary Kriss, D.D

Cathedral Building in America: A Missionary Cathedral in Utah By the Very Reverend Gary Kriss, D.D. I “THERE IS NO fixed type yet of the American cathedral.”1 Bishop Daniel S. Tuttle’s comment in 1906 remains true today as an assessment of the progress of the cathedral movement in the Episcopal Church. In organization, mission, and architecture, American cathedrals represent a kaleidoscope of styles quite unlike the settled cathedral system which is found in England. It may fairly be said that, in the development of the Episcopal Church, cathedrals were an afterthought. The first cathedrals appear on the scene in the early 1860s, more than two hundred fifty years after Anglicans established their first parish on American soil. So far removed from the experience of English cathedral life, it is remarkable that cathedrals emerged at all—unless it might be suggested that by the very nature of episcopacy, cathedrals are integral to it. “I think no Episcopate complete that has not a center, the cathedral, as well as a circumference, the Diocese.”2 The year was 1869. William Croswell Doane, first Bishop of Albany, New York, was setting forth his vision for his Diocese. Just two years earlier, Bishop Tuttle had set out from his parish in Morris, New York, (which, coincidentally, was in that section of New York State which became part of the new Diocese of Albany in 1868) to begin his work as Missionary Bishop of Montana with Idaho and Utah. In 1869, Bishop Tuttle established his permanent home in Salt Lake City, and within two years, quite without any conscious purpose or design on his part, he had a cathedral. -

The Senior Canterbury Pilgrimage the Dean’S Letter Planning for Berkeley’S Exceptional Future

BerkeleyatYALE Spring 2015 • Vol. 6, No. 2 The Senior Canterbury Pilgrimage The Dean’s Letter Planning for Berkeley’s Exceptional Future Dear Alumni and Friends, Recent crises in Episcopal seminary education pects for colleges and universities in general, have caught much attention; but the really diffi- including the likelihood of drastic change for cult issues for theological education today may be some institutions and closures of others. The more deep-seated than passing conflicts between list of issues should be remarkably familiar to deans, faculty members, or trustees. seminary educators. They included: Conflict is often a symptom, rather than the • Ensuring that universities are providing the root of a problem. Underneath strained relation- skills, tools, and experiences that employers ships and competing strategies lies the harsh real- actually want and need. ity of declining seminary enrollments and rising • Working to overcome the impact of rising costs, and differing views about how to work costs on students and on their post-educa- together in addressing them. tional choices. Softening demand for theological education • Considering how the whole “eco-system” of reflects not only the shifting sands of religious higher education needs to change. affiliation in the U.S. and beyond, but also doubts about the continued relevance of seminary educa- Barber and his colleagues argue that the tion, even for aspiring clergy. In remarks given to emergence of cheaper online degrees, and of the the Executive Council of the Episcopal Church free Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) like those of Open Yale, will not only attract Survival is not enough; and to work merely for survival some students away from traditional university courses but force degree granting institutions in or to adapt just to exist would be pointless…. -

Journal of the 178Th Convention

THE JOURNAL OF THE 178TH CONVENTION OF THE DIOCESE OF THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH OF LOUISIANA 1623 SEVENTH STREET NEW ORLEANS, LA 70115 FEBRUARY 27 & 28, 2015 TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH NEW ORLEANS, LA MINUTES OF THE SPECIAL BUDGET MEETING OF THE 178TH CONVENTION TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH, BATON ROUGE OCTOBER 31, 2015 Table of Contents Diocesan Staff ............................................................................................................ 3 Standing Committee Membership ............................................................................. 4 Executive Board Membership .................................................................................... 5 Church Directory (by city) ......................................................................................... 6 Diocesan Clergy Directory ...................................................................................... 13 Clergy by Order of Canonical Residence ................................................................ 31 Necrology (as of 3/1/2015) ...................................................................................... 35 Deaneries .................................................................................................................. 36 Statistical Summary from the Bishop ...................................................................... 39 Official Acts of the Bishop ...................................................................................... 41 Canons of the Diocese............................................................................................. -

Response by the Very Reverend Peter Elliott

The Very Reverend Peter Elliott Dean of the Diocese of New Westminster Rector of Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver, BC Member of the Anglican Consultative Council It is heartening to read the statement from the 5th Consultation of Anglican Bishops in Dialogue from Coventry England, May 2014 A Testimony of Our Journey Towards Reconciliation. These meetings between bishops from Africa and North America, continuing conversations begun at the 2008 Lambeth Conference, are encouraging signs of hope. I found the location of this fifth meeting in Coventry Cathedral--with its rich heritage and leadership in the ministry of reconciliation--and the participation of the current Archbishop of Canterbury, inspiring. The creative melding together of themes from St. Paul’s two letters to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 13: 12; 2 Corinthians 5: 18-20) was particularly fascinating linking together an existential agnosticism (‘…now we see in a mirror dimly…now I know only in part…’) with a clarion call to reconciliation (‘..Christ…has given us the ministry of reconciliation…’). Holding together the sense of not knowing with the eschatological call to reconciliation articulates an important acknowledgement of the deep need to listen, understand and work tirelessly toward the reconciliation to which we are called. There are numerous phrases in the bishops’ testimony that offer hope to a communion deeply affected by differences in theological and ethical views: it was encouraging to read, “It is in this middle ground between what was and what will be that all Christian people stand, but it is the particular vocation of Anglicans to stand in the middle, to be the incarnate people of reconciliation.” The great via media, the comprehensiveness characteristic of classical Anglicanism has, sadly, been overshadowed, in recent years by an Internet-fueled conflict between competing theologies. -

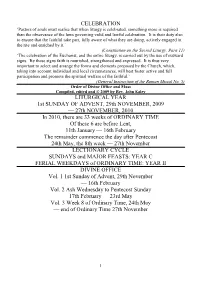

Ordo2010.Pdf

CELEBRATION ‘Pastors of souls must realise that when liturgy is celebrated, something more is required than the observance of the laws governing valid and lawful celebration. It is their duty also to ensure that the faithful take part, fully aware of what they are doing, actively engaged in the rite and enriched by it.’ (Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Para 11) ‘The celebration of the Eucharist, and the entire liturgy, is carried out by the use of outward signs. By these signs faith is nourished, strengthened and expressed. It is thus very important to select and arrange the forms and elements proposed by the Church, which, taking into account individual and local circumstances, will best foster active and full participation and promote the spiritual welfare of the faithful.’ (General Instruction of the Roman Missal No. 5) Order of Divine Office and Mass Compiled, edited and © 2009 by Rev. John Ealey LITURGICAL YEAR 1st SUNDAY OF ADVENT, 29th NOVEMBER, 2009 — 27th NOVEMBER, 2010 In 2010, there are 33 weeks of ORDINARY TIME Of these 6 are before Lent, 11th January — 16th February The remainder commence the day after Pentecost 24th May, the 8th week — 27th November LECTIONARY CYCLE SUNDAYS and MAJOR FEASTS: YEAR C FERIAL WEEKDAYS of ORDINARY TIME: YEAR II DIVINE OFFICE Vol. 1 1st Sunday of Advent, 29th November — 16th February Vol. 2 Ash Wednesday to Pentecost Sunday 17th February — 23rd May Vol. 3 Week 8 of Ordinary Time, 24th May — end of Ordinary Time 27th November 1 ABBREVIATIONS Adv: Advent Ant(s): Antiphon(s) Ap. App: Apostle. Apostles B: Bishop Cr: Creed Comm: Common Cps: Companions D: Doctor E.P: Eucharistic Prayer Ev. -

Surname Givens Dateevent Placeevent Age/Born Spouse Date

Surname Givens Event DateEvent PlaceEvent Age/Born Spouse Date Page Info/Kin AASLAND Bjarne Norman Marr 10-Apr-1954 Comox United Audrey Bell 14-Apr-1954 9 Son of M/M Olaf Aasland of Castlegar Church Lancashire ABBOTT (boy) Birth 18-Jul-1951 Comox 26-Jul-1951 8 Son of M/M Edward Abbott of Courtenay ABBOTT (girl) Birth 23-Apr-1951 Campbell River 3-May-1951 2 Dtr/o M/M Thos. Abbott of Campbell River ABELL (girl) Birth 26-Jul-1955 Comox 27-Jul-1955 3 Dtr/o M/M Edward Abell, RCAF, Comox ABOLINS Emil Death3-Nov-1953 Cumberland age 80 not named 5-Nov-1953 11 Retired professor from Latvian University, father of Mrs. Ed Olins of Fanny Bay, service at Cumberland United Church, Banks FH, cremation in Vancouver (See Fanny Bay news, 12 Nov p. 10) ABRAMS Seymour Death20-May-1951 Nanaimo age 60 Mrs. Abrams 24-May-1951 1 Son of James Abrams, early merchant of Nanaimo, 3 children and other family named, former customs inspector at Union Bay, funeral in Nanaimo. See also 31 May p. 2 Union Bay People and page 7 Paper Carries Editorial ACORN (girl) Birth 11-Mar-1955 Comox 16-Mar-1955 7 Dtr/o M/M K. Acorn of Courtenay ADAMS (girl) Birth 24-Aug-1955 Victoria 31-Aug-1955 8 Dtr/o M/M L. Adams, nee Pauline Downey ADAMS Earl Laurie Marr 4-Jul-1954 Tofino Norma Annie 14-Jul-1954 8 Son of M/M G.G. Adams of Willow Point Arnet ADAMS Howard Marr 5-Feb-1955 Port Alberni Shirley Dutton 9-Feb-1955 3 Attended by Shirley's relatives (Bowser news) ADAMS Marion Rose Marr 18-Dec-1954 Campbell River James Bruce 22-Dec-1954 8 Dtr/o M/M George G. -

1 in the CIRCUIT COURT, CITY of ST. LOUIS TWENTY-SECOND JUDICIAL CIRCUIT 2 STATE of MISSOURI 3 DOE 1, ) ) 4 Plaintiff, ) ) 5 Vs

ARCHBISHOP ROBERT CARLSON **CONFIDENTIAL** 5/23/2014 Page 1 1 IN THE CIRCUIT COURT, CITY OF ST. LOUIS TWENTY-SECOND JUDICIAL CIRCUIT 2 STATE OF MISSOURI 3 DOE 1, ) ) 4 Plaintiff, ) ) 5 vs. ) ) 6 Archdiocese of St. Paul and ) Minneapolis, Diocese of ) 7 Winona and Thomas Adamson, ) ) 8 Defendants. ) 9 10 11 VIDEOTAPED DEPOSITION OF ARCHBISHOP ROBERT CARLSON 12 Taken on behalf of Plaintiff 13 May 23, 2014 14 (Starting time of the deposition: 10:11 a.m.) 15 **CONFIDENTIAL** 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 MIDWEST LITIGATION SERVICES www.midwestlitigation.com Phone: 1.800.280.3376 Fax: 314.644.1334 ARCHBISHOP ROBERT CARLSON **CONFIDENTIAL** 5/23/2014 Page 2 1 I N D E X O F E X A M I N A T I O N 2 3 Page 4 Questions by Mr. Anderson ........................ 8 5 6 I N D E X O F E X H I B I T S 7 Exhibit No. 296 (Letter) ......................... 6 Exhibit No. 297 (Meeting Minutes) ................ 6 8 Exhibit No. 239 (Deposition Transcript) .......... 6 Exhibit No. 299 (Letter of Assignment) ........... 6 9 Exhibit No. 301 (Memo) ........................... 6 Exhibit No. 302 (Memo) ........................... 6 10 Exhibit No. 303 (Memo) ........................... 6 Exhibit No. 319 (Letter) ......................... 6 11 Exhibit No. 304 (Memo) ........................... 6 Exhibit No. 101 (Newspaper Article) .............. 6 12 Exhibit No. 305 (Memo) ........................... 6 Exhibit No. 275 (Memo) ........................... 6 13 Exhibit No. 276 (Letter) ......................... 6 Exhibit No. 282 (Memo) ........................... 6 14 Exhibit No. 245 (Memo) ........................... 6 Exhibit No. 250 (Memo) ........................... 6 15 Exhibit No. 246 (Letter) ......................... 6 Exhibit No. -

Scottish Episcopal Church Diocese of Brechin

Scottish Episcopal Church Diocese of Brechin Diocesan Synod Saturday 11th March 2017 Diocesan Centre St John Baptist Church Dundee Membership of Synod Rules of Order of Synod Constitution of Synod Can be found at the end of the book Scottish Episcopal Church DIOCESE OF BRECHIN Scottish Charity No SC 016813 Agenda for Diocesan Synod – Saturday, 11th March 2017 9.30am Synod Eucharist followed by coffee 10.45am Commencement of business. During the morning our Guest Speaker is Jenny Marra MSP for North East Scotland “Keeping Faith in Politics” Lunch will be at 12.45pm, business resumes at 13.30pm 1. Roll call of members – by attendance slips and apologies for absence. 2. Minutes of previous Diocesan Synod March 2016 Paper A 3. Diocesan Statistics for 2016 Paper B 4. Diocesan Personnel Paper C 5. Report of the Election of Lay and Alternate Representatives for 2017 Paper D 6. Report of the Standing Committee Paper E 7. Report of the Diocesan Council Paper F 8. Report from Diocesan Mission Officer Paper G 9. Report from Diocesan Ministry Officer Paper H 10. Diocesan Buildings Committee Report for 2016 Paper I 11. Report from Information and Communications Officer Paper J 12. Protection of Vulnerable Groups Report Paper K 13. Companion Dioceses Officer Report Paper L 14. Diocesan Youth Report Paper M 15. Diocesan Elections and Appointments Paper N 16. Provincial Elections and Appointments Paper O 17. Canonical Changes – Canons 63,22,31 Paper P 18. Dissolution of the Charge of St John the Baptist, Dundee (Canon 36) Paper Q 19. Cathedral Motion – Review of Canon 54 Paper R 20. -

Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral

SCOTTISH EPISCOPAL CHURCH DIOCESE OF BRECHIN THE CONSECRATION OF THE VERY REVEREND ANDREW SWIFT AS BISHOP OF BRECHIN IN THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF ST PAUL, DUNDEE ON SATURDAY 25TH AUGUST 2018 WELCOME TO ST PAUL'S CATHEDRAL A warm welcome to all who have travelled from far and near. We gather today to celebrate the Consecration of the Very Revd Andrew Swift as Bishop of the Diocese of Brechin. We welcome the Most Revd Mark Strange, Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, who will preside over the Ordination, and The Rt Revd Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, Bishop of Ripon, who will preach today. We also welcome family and friends of Bishop-elect Andrew; his friends and former colleagues from the Diocese of Argyll & The Isles; civic guests from Dundee and Angus; ecumenical guests; bishops and clergy from the various dioceses of the Scottish Episcopal Church and beyond, along with the bishops of our companion dioceses of Iowa and Swaziland. ABOUT TODAY’S SERVICE: • The Order of Service is contained in this booklet. • You are invited to join in saying the words in bold type and to join in singing all the hymns and congregational music throughout the liturgy. • We are most grateful to have Frikki Walker, Director of Music at St Mary’s Cathedral, Glasgow with us to conduct the choir today. • Directions for standing/sitting/kneeling are given, but please feel free to do what is most comfortable for you during the service. • All are invited to receive Communion at this service (gluten-free wafers will be available). • If you use a hearing aid, switch it to the ‘T’ position for direct access to the sound system.