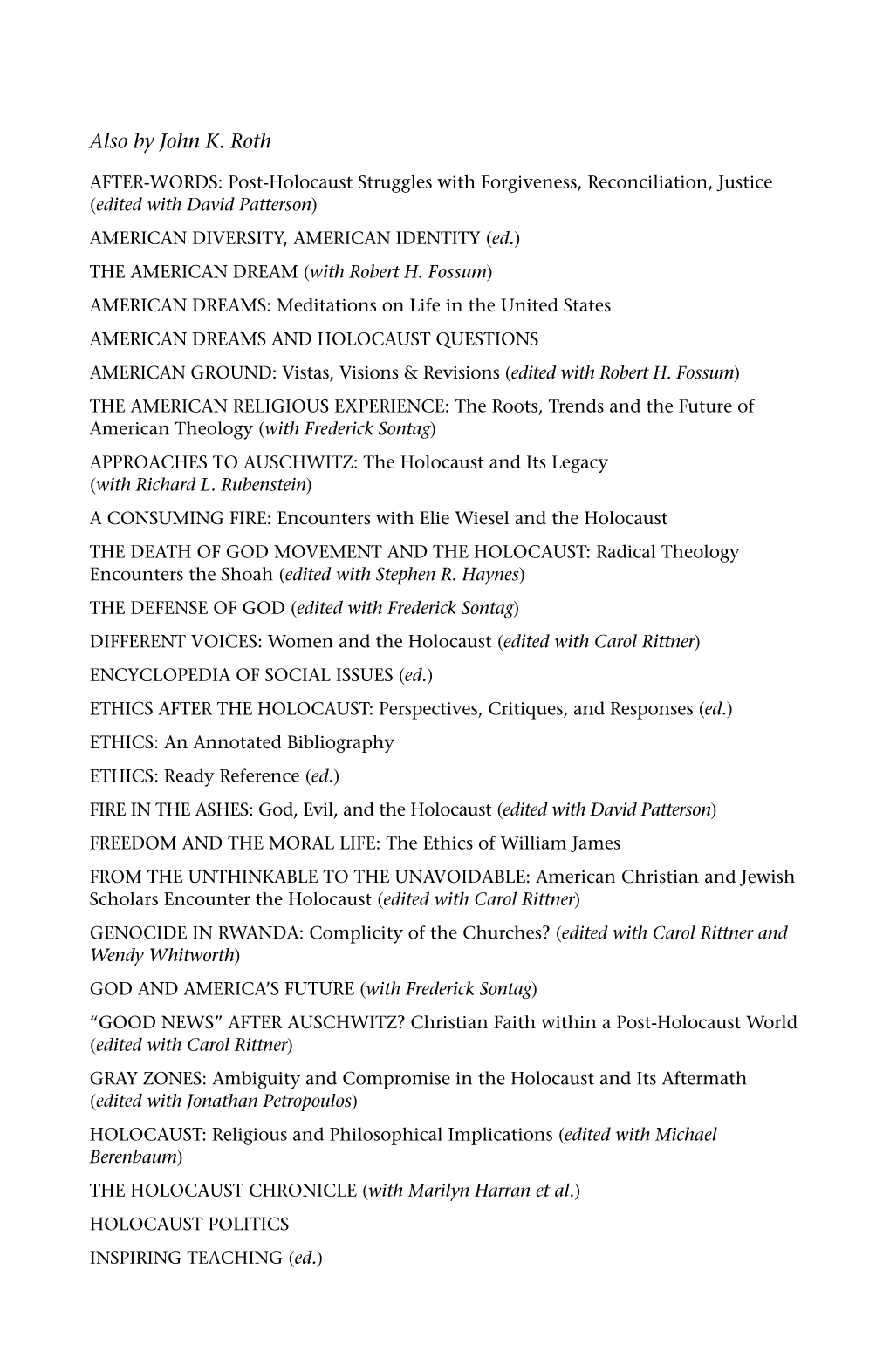

Also by John K. Roth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION Drawn from Life: Mary Douglas's Personal Method

INTRODUCTION Drawn from life: Mary Douglas’s personal method Richard Fardon Mary Douglas (1921–2007) was the most widely read British anthropolo- gist of the second half of the twentieth century. Her writings continue to inspire researchers in numerous fields in the twenty-first century.1 This vol- ume of papers, first published over a period of almost fifty years, provides insights into the wellsprings of her style of thought and manner of writing. More popular counterparts to many of Douglas’s academic works – either the first formulation of an argument, or its more general statement – were often published around the same time as a specialist version. These first thoughts and popular re-imaginings are particularly revealing of the close relation between Douglas’s intellectual and personal concerns, a convergence that became more overt in her late career, when Mary Douglas occasionally wrote autobiographi- cally, explaining her ideas in relation to her upbringing, her family, and her experiences as both a committed Roman Catholic and a social anthropologist in the academy. The four social types of her theoretical writings – hierarchy, competition, the enclaved sect, and individuals in isolation – extend to remote times and distant places, prototypes that literally were close to home for her. This ability to expand and contract a restricted range of formal images allowed Mary Douglas to enter new fields of study with startling rapidity, to link unlikely domains of thought (through analogy, most frequently with religion), and to accommodate the most diverse examples in comparative frameworks. It was the way, to put it baldly, she made things fall into place. -

The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- Doch

University of Szeged Faculty of Arts Doctoral Dissertation The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- doch Dávid Sándor Szőke Supervisors: Dr. Zoltán Kelemen Dr. Anna Kérchy 2021 Acknowledgements I have a great number of people to thank for their support throughout this thesis, whether this support has been academic, financial, or spiritual. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Zoltán Kelemen and Dr Anna Kérchy for their unending help, encouragement and faith in me during my research. Their knowledge about the Holocaust, 20th century English woman writers and minorities has given exceptional depth to my understanding of Murdoch, Steiner, Canetti and Adler. The eye-opening essays and lectures by Dr Peter Weber about the Romanian painter and Holocaust survivor Arnold Daghani’s time in England provided a genesis for this thesis. Had it not for him, I would not have thought about putting Murdoch’s thinking in the context of Cen- tral European refugee literature and culture during and after the Second World War. This thesis owes much to the 2017 Holocaust Conference in Szeged (19 October) and the 2019 International Holocaust Conference in Halle (14-16 November). I would like to express my gratitude to the March of the Living Hungary, the Holocaust Memorial Centre Budapest, the Memory Point of Hódmezővásárhely, the synagogues of Szeged and Hódmezővásárhely, Professor Werner Nell (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Thomas Bremer (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Sue Vice (University of Shef- field), and Dr Zoltán Kelemen for making these events possible. During my PhD, as part of the Erasmus ++ programme I spent an entire year at Martin- Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, where I made a great deal of research about the German coming to terms with the past. -

Pomona College Commencement 2009 May 17, 2009

Presentation of the Trustees’ Medal of Merit to Frederick Sontag Pomona College Commencement 2009 May 17, 2009 Presented by Stewart Smith, Chairman of the Board of Trustees Good morning. The Board of Trustees is periodically honored to award the Trustees’ Medal of Merit to persons who have rendered outstanding service to Pomona or who have brought distinction to this institution through their actions or achievements. Today the Trustees are pleased to bestow such an award on Professor Frederick Sontag. Fred Sontag is, by any measure, an extraordinarily magnanimous member of this community— one who has deeply affected generations of students at Pomona College, which has been his academic and spiritual home for 57 years. Born in Long Beach in 1924, Fred and his remarkable wife Carol arrived in Claremont in 1952 after he had graduated from Stanford University in 1949 and earned M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Yale University in 1951 and 1952. Fred’s academic discipline is philosophy, and the nature and breadth of his special interests— metaphysics, philosophy of religion, philosophical psychology, existentialism, and philosophical theology—are brilliantly reflected in the profoundly influential life he has led. He has been a gifted teacher and an insightful author of nearly 30 scholarly books, while contributing almost 100 essays and articles to major publications and more than 300 articles and opinion pieces to professional journals, magazines, and newspapers. While Fred’s faculty colleagues at Pomona and around the world have long celebrated his extraordinary scholarly achievements and the immense range of his academic interests in philosophy, religion, and literature, today we honor Fred Sontag for his compassionate mentorship and counseling of students. -

World Hau Books

WORLD Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WORLD AN ANthrOPOLOgical EXAMINatION João de Pina-Cabral The Malinowski Monographs Series Hau Books Chicago © 2017 Hau Books and João de Pina-Cabral The Malinowski Monographs Series (Volume 1) The Malinowski Monographs showcase groundbreaking monographs that contribute to the emergence of new ethnographically-inspired theories. In tribute to the foundational, yet productively contentious, nature of the ethnographic imagination in anthropology, this series honors Bronislaw Malinowski, the coiner of the term “ethnographic theory.” The series publishes short monographs that develop and critique key concepts in ethnographic theory (e.g., money, magic, belief, imagination, world, humor, love, etc.), and standard anthropological monographs—based on original research—that emphasize the analytical move from ethnography to theory. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-24-3 LCCN: 2016961546 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi chapter one World 1 chapter two Transcendence 31 -

Introduction: After Society

INTRODUCTION AFTER SOCIETY João Pina-Cabral and Glenn Bowman Introductory Remarks This book brings together a group of scholars who were shaped by Oxford anthropology in the late 1970s and early 1980s, each reflect- ing on their academic trajectories. This was a period of major political and academic change in Great Britain and, more generally, around the globe. A decade earlier, the student revolts had had a profound effect on the way the social sciences saw their role in society. Yet, it is only with the impact of the neoliberal reaction, at the time of Mrs Thatcher’s first government, that the full implications of the earlier crisis made themselves felt in anthropology. These implications were both internal, in theoretical terms, leading to a deep questioning of the central tenets that had shaped the social sciences throughout the twentieth century; and external, in academic terms, when scholarly discourse was suddenly treated by those in power as being largely irrelevant to the economy and to society – a kind of perverse luxury. Those of us who started our anthropological careers at the time faced the need to respond to a further set of aspects of intellectual decentring: (a) a second wave of psychoanalytic feminism was mak- ing important theoretical inroads; (b) poststructuralist critique was upturning the dominant individualist consensus that had dominated since the Second World War; (c) postmodernist dispositions were challenging traditional modes of ethnographic writing; and (d) a new Marxist-inspired postcolonial historiography was affecting the assumed perspectival roles of anthropological research, proposing radically new approaches to the very meaning of power. -

William Collins Donahue

William Collins Donahue 816 North St. Peter Street ● South Bend, IN 46617 Email: [email protected] Cell: 919.428.5829 Department of German & Russian Languages & Literatures University of Notre Dame ● 318 O’Shaughnessy Hall Notre Dame, IN 46556 ● 574.631.5572 Current Appointments University of Notre Dame: Director, Nanovic Institute for European Studies John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Professor of the Humanities Professor of German Concurrent Professor of Film, Television, and Theatre Duke University Adjunct Professor of German Studies and Member of the Duke Graduate School Faculty (2015 – present) University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill: Member, Graduate School Faculty (2011 – present) Employment History University of Notre Dame: Chair, Department of German & Russian, July, 2015 – December, 2018 Fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, 2015-18 Duke University Bishop-MacDermott Family Professor of Germanic Languages & Literature (2013-15) Member, Bass Society of Fellows (2013-15) Chair, Department of Germanic Languages and Literature (2008 – 2014) Professor, Germanic Languages & Literature (2011-15) Professor, The Program in Literature (2011-15) Member of the Faculty of Jewish Studies (2006-15) and the Jewish Studies Executive Committee (2006—2014) Academic Director, Duke in Berlin (semester, year, and engineering programs; 2006- 15). Advising, Curriculum and Instructional Review, Program design, Personnel Review, Assessment. Duke Today story about Duke in Berlin press coverage in Berlin’s Der Tagesspiegel: http://today.duke.edu/2012/10/germancoverage Director and Founder, Duke-Rutgers Summer in Berlin (2006-15). Six week summer program. University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill: Member, Graduate School Faculty (2011 – present) Adjunct Professor of German Studies (2011-15) Adjunct Associate Professor of German Studies (2008–11). -

Frederick Sontag Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c89p37ww No online items Frederick Sontag Papers Jamie Weber and Sean Stanley Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library 800 North Dartmouth Avenue Claremont, CA 91711 Phone: (909) 607-3977 Email: [email protected] URL: https://library.claremont.edu/scl/ © 2021 The Claremont Colleges Library. All rights reserved. Frederick Sontag Papers PC.0005 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Frederick Sontag Papers Dates: 1944-2008 Collection number: PC.0005 Creator: Sontag, Frederick H., 1924-2009 Extent: 13.6 Linear Feet(12 record cartons, 4 document boxes) Repository: Claremont Colleges. Library. Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library, Claremont, CA 91711. Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Frederick Sontag, Pomona College professor of philosophy, author, and minister in the United Church of Christ. Over his five-decade career at Pomona College, Sontag served as Philosophy Department Chair and as a visiting professor for a number of theological institutions. He authored numerous publications and articles, his most well-known being "Sun Myung Moon and the Unification Church" (1977). The collection includes correspondence, articles, book reviews, teaching materials, sermons, lectures, and research materials. Please consult repository. Language of Material: Languages represented in collection: English. Administrative Information Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights All requests for permission to reproduce or to publish must be submitted in writing to the Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Frederick Sontag Papers (PC-0005). Pomona College Archives, Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library, Claremont, California. Provenance/Source of Acquisition Gift of the Sontag Family, 2011. Accruals Additions to the collection are not anticipated. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Adler, J. and R. Fardon. 1999a. ‘An Oriental in the West: The Life of Franz Baermann Steiner’. In: Taboo, Truth and Religion: Franz Baermann Steiner Selected. Writings ed. J. Adler and R. Fardon. Oxford: Berghahn. ——— and ——— 1999b. ‘Orientpolitik, Value and Civilisation: The Anthropological Thought of Franz Steiner’. In: Orientpolitik, Value and Civilisation: Franz Baermann Steiner Selected Writings ed. J. Adler and R. Fardon. Oxford: Berghahn. Alexander, C. 1996. The Art of Being Black. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Annan, N. 1990. Our Age: Portrait of a Generation. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Appadurai, A. 1996. ‘Diversity and Disciplinarity as Cultural Artefacts’. In: Disciplinarity and Dissent in Cultural Studies, ed. C. Nelson and D.P. Gaonkar. London: Routledge. Ardener, E. and S. Ardener. 1965. ‘A Directory Study of Social Anthropologists’. British Journal of Sociology 16: 295–315. Asad, T. ed. 1973. Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter. London: Ithaca Press. Bagley, C. 1985. ‘Review of Racial and Ethnic Competition by Michael Banton’. American Journal of Sociology 91 (1): 197–99. Banton, M. 1954. The Coloured. Quarter: Negro Immigrants in an English City. London: Jonathan Cape. ——— 1959. White and Coloured: The Behaviour of British People towards Coloured. Immigrants. Oxford: Alden Press. ——— ed. 1965a. The Relevance of Models for Social Anthropology: Asa Monographs 1. London: Tavistock. ——— ed. 1965b. Political Systems and the Distribution of Power: Asa Monographs 2. London: Tavistock. ——— ed. 1966a. Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion: Asa Monographs 3. London: Tavistock. ——— ed. 1966b. The Social Anthropology of Complex Societies: Asa Monographs 4. London: Tavistock. ——— 1973. ‘The Future of Race Relations Research in Britain: The Establishment of a Multi-Disciplinary Research Unit’. -

The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Murdoch

University of Szeged Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Doctoral School for Literary Studies Department of Comparative Literature Doctoral Dissertation The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Murdoch Dávid Sándor Szőke Supervisors: Dr. Zoltán Kelemen Dr. Anna Kérchy 2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction A Reflection on the Past ........................................................................................................ 4 Chapter One Exile in England: Elias Canetti, Franz Baermann Steiner, and H.G. Adler in London……..23 Chapter Two Uprootedness and the Search for Identity in Under the Net and A Severed Head…………..68 Chapter Three Displacement and Exile Identity in The Flight from the Enchanter ……………...……… 105 Chapter Four The Two Kind of Jews in The Italian Girl …………..…………………………………. 124 Chapter Five Reconciliation and Forgiveness in The Nice and the Good …………………...……….… 145 Conclusion…………………………...…….…………………………………………….166 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 170 2 Summary of Theses The goals of my dissertation In my dissertation, I provide a comparative analysis of the interrelationship between the German exile literature and Iris Murdoch’s early novels. In this work, I explain how the issues of trauma, memory, displacement and power in Murdoch’s fiction were informed by her intellectual encounters with three German-speaking exiled authors, Elias Canetti, Franz Baermann Steiner and H.G. Adler. Concentrating on five novels from Murdoch’s early period, Under the Net (1954), The Flight from the Enchanter (1956), A Severed Head (1961), The Italian Girl (1964), The Nice and the Good (1968), I explore how the post-war trauma and the questions of displacement, power and making sense of the past had become central to her. What makes these works curious to discuss is that, in them, she sets up the diagnosis of post-war societies, which are suffering between two totalitarian powers, where exile is a symbol of the modern state of being that is characterized by rootlessness and alienation. -

Sects, Cults and Mainstream Religion

sects, cults and mainstream religion a cultural interpretation of new religious movements in america dewey d. Wallace, jr. Few aspects of American religious life have called forth more comment than the proliferation of new religious groups, the so-called sects and cults of both learned and popular discussion. But defining what is meant by sect and cult and relating them to some of the broad streams of American cultural life have proved difficult, not least because so many students of the subject have emphasized the formal (usually sociological) characteristics of these groups rather than the specific nature of their teachings. Some scholars, however, have countered that trend. One such person is A. Leland Jamison, who attempted to define and distinguish sect and cult on the basis of content, the cult claiming a new revelation while the sect defined itself by a selective emphasis that protested the apostasy of some parent body.1 Jamison's distinction has been useful in the classification of groups by the content of their teachings, but is less useful for relating these groups to the wider cultural context. We will bypass some large problems in this essay through a simplified definition: whatever else may be meant by the terms ''sect" and "cult" (and the term "cult" is becoming increasingly difficult to use in a neutral sense), they are certainly small religious groups that are generally per ceived as being outside the mainstreams of the religious life of a commu nity and that hold views which the larger society finds unusual. Proceeding from that definition, the present essay is an effort, mainly through 0026-3079/85/2602-0005$01.50/0 5 examining secondary literature, to analyze the teachings of some of the new religious groups in America in relation to the American mainstream. -

JASO-Online Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford

JASO-online Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford • In association with the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography (University of Oxford) and Oxford University Anthropology Society New Series, Volume XII, no. 1 (2020) JASO-online Editor: Robert Parkin Web Editor: David Zeitlyn ISSN: 2040-1876 © Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 51 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6PE, UK, 2020 All rights reserved in accordance with online instructions. NB: Copyright for all the articles, reviews and other authored items in this issue falls under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence (see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/). Download current issues and back numbers for free from: http://www.anthro.ox.ac.uk/publications/journal-of-the-anthropological-society-of- oxford/ CONTENTS Obituary: Nicholas Justin ‘Nick’ Allen, 1939-2020 (Robert Parkin) 1-13 Alina Berg, Faith and agency on the Camino: walking between shared ‘substance’ and cultural (dis)appearance 14-43 Deepak Prince, A stain in the picture 44-68 Benedict Taylor-Green,‘To anthropology, from meat prison’ 69-91 Yura Yokoyama, From ethnic settlement to cultural coexistence: German and Japanese gaúchos in Ivoti and indicators of culturally symbiotic place-making 92-109 Anita Sharma, The Bakkarwal of Jammu and Kashmir: negotiating the commons 110-120 BOOK REVIEWS 121-130 Holger Jebens (ed.), Nicht alles verstehen: Wege und Umwege in der deutschen Ethnologie (Robert Parkin) 121-124 Konstantinos Kalantzis, Tradition in the frame: photography, power, and imagination in Sfakia, Crete (Roger Just) 125-127 Darryl Li, The universal enemy: jihad, empire, and the challenge of solidarity (Jessie Barton-Hronešová) 128-130 FIFTY YEARS OF JASO With this issue, JASO celebrates fifty years since Brian Street and Paul Heelas edited and produced the first issue of the Journal back in 1970. -

November 2016 New Arrivals Catalog

New Arrivals November 2016 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 [email protected] * http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store) Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- phone not answered). Catalog listings are formatted as follows: Item No. Author Title Publisher No. of Pages Condition Binding Year Cost ABBREVIATIONS FOR BINDING: dj= hardcover w/dustjacket hc= hardcover w/out dustjacket L= full or half leather pb = paperback Re-= re-bound, usually in buckram V=vinyl or leatherette ABBREVIATIONS FOR CONDITION: If no condition is noted, you may assume the book is in very good to fine condition. Our abbreviations used to describe defects are as follows: As is= condition is poor; details available upon request br= broken binding ch= chipped or torn (usually refers to dust jacket condition) Fx= foxing highlt= highlighting m= musty mks or ul= underlining, highlighting, or marginalia pncl= pencil marks S or st = stained or grubby sh= shaken or weak hinges sl= slight v= very wr or wrn= worn (usually in reference to exterior) wrp= warped X or XL= ex- library Y or yellow = yellowed pages OUR TERMS: We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and PayPal. Available books that you have requested will be reserved for 1 business day after our order confirmation, to allow time for payment arrangements. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package.