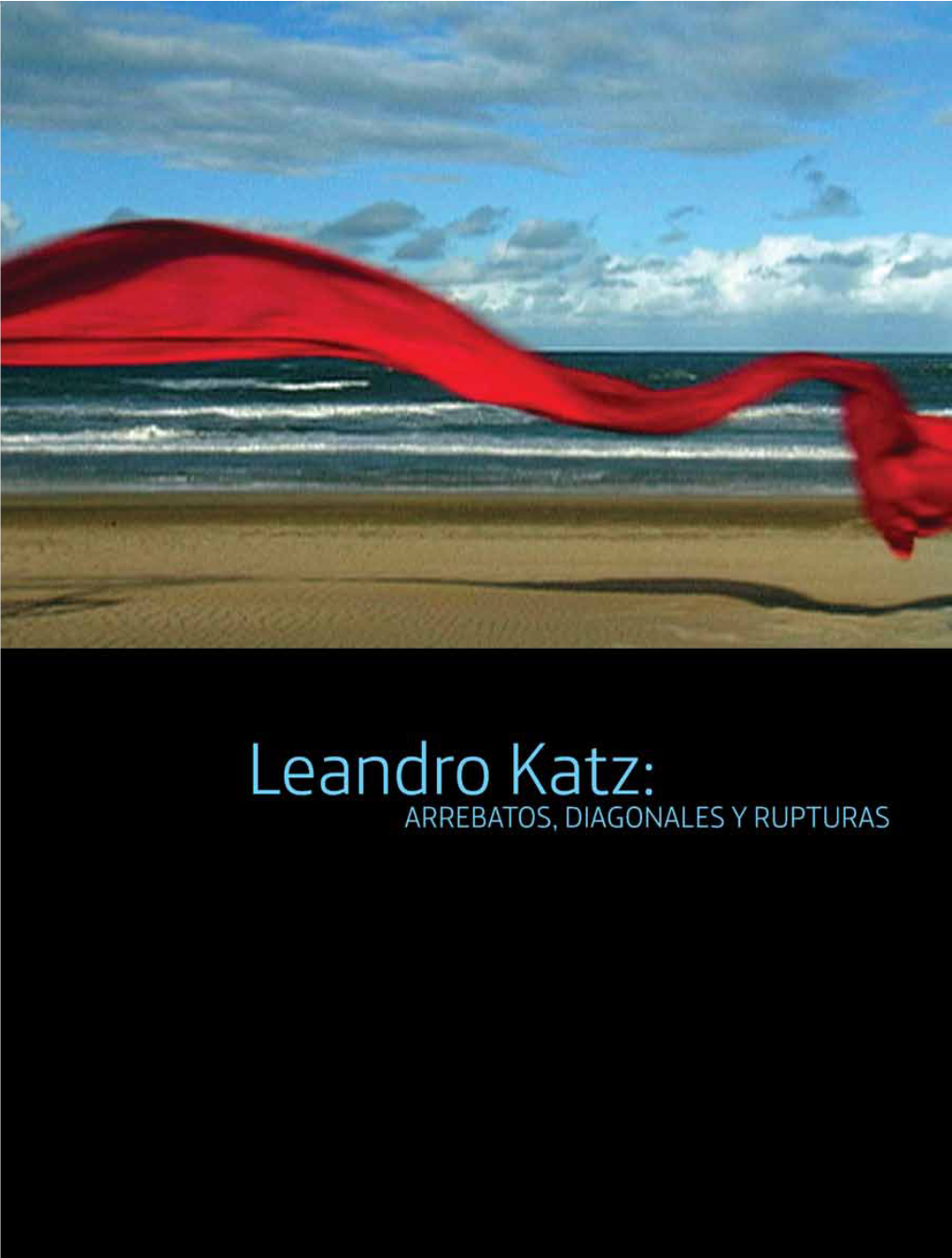

Arrebatos, Diagonales Y Rupturas Catálogo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CABAEL, FELIPE, 73, of Mililani, Died Feb. 17, 2008

CABAEL, FELIPE, 73, of Mililani, died Feb. 17, 2008. Born in Kahuku. Computer electrical technician; U.S. Marine Corps master sergeant; lifetime member of the Disabled Veterans of America. Survived by sons, Laird and Mike; daughters, Cydonie, Jennifer Cabael-Erickson and Debbie Cabael-Smith; brothers, Ernesto and Alfredo; sister, Lolita Camit; grandchildren; great- grandchildren. Visitation 9 to 10 a.m. Tuesday at Hawaiian Memorial Park Mortuary; service 10 a.m.; burial 2 p.m. at Hawai'i State Veterans Cemetery. Aloha attire. Flag indicates service in the U.S. armed forces. [Honolulu Advertiser 7 March 2008] CABAG, MERCEDES T. MAHIN ABELLA, 91, of Pearl City, died Nov. 20, 2008. Born in ‗Ewa. Retired from Waipahu High School and Pearlridge Hospital. Survived by daughters, Edna Lagon and Laura Hood; son, Peter Mahin; nine grandchildren; 16 great-grandchildren; eight great-great-grandchildren. Visitation 9 a.m. Thursday at Our Lady of Good Counsel Catholic Church; Mass 10 a.m. Burial 1:30 p.m. at Mililani memorial Park. Lei welcome. Casual attire. Arrangements by Mililani Memorial Park & Mortuary. Flag indicates service in the U.S. armed forces. [Honolulu Advertiser 8 December 2008] Cabalar, Marcelino Cachola Sr., Feb. 1, 2008 Marcelino Cachola Cabalar Sr., 85, of Kapolei, a retired Ameron HCD spinner pipe operator, died in Hawaii Medical Center West. He was born in Ilocos Norte, Philippines. He is survived by children Estrellita Soria and Eddie and Marcelino C. "Masa" Cabalar Jr., Estrella C. Tavares and Edwina P. Sedeno; 17 grandchildren; and 20 great-grandchildren. Services: 10 a.m. Tuesday at Mililani Mortuary-Waipio, makai chapel. -

College of Education Commencement 2021

COLLEGE OF EDUCATION COMMENCEMENT 2021 PB Welcome to CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY LONG BEACH California State University, Long Beach is a member of the 23-campus California State University (CSU) system. The initial college, known then as Los Angeles-Orange County State College, was established on January 29, 1949, and has since grown to become one of the state’s largest universities. The first classes in 1949 were held in a converted apartment building on Anaheim Street and the cost to enroll was just $12.50. The 169 transfer students selected from the 25 courses offered in Teacher Education, Business Education, and Liberal Arts which were taught by 13 faculty members. Enrollment increased in 1953 when freshman and sophomore students were admitted. Expansion, in acreage, degrees, courses and enrollment continued in the 1960s, when the educational mission was modified to provide instruction for undergraduate and graduate students through the addition of master’s degrees. In 1972, the California Legislature changed the name to California State University, Long Beach. Today, more than 37,000 students are enrolled at Cal State Long Beach, and the campus annually receives high rankings in several national surveys. What students find when they come here is an academic excellence achieved through a distinguished faculty, hard-working staff and an effective and visionary administration. The faculty’s primary responsibility is to create, through effective teaching, research and creative activities, a learning environment where students grow and develop to their fullest potential. This year, because of the pandemic, we will celebrate the outstanding graduates of two classes – 2020 and 2021. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Attendees As of 9.27

Honorific First Name Middle Name Last Name Title Company City State Country Attendee Type Student, B.S. Computer Engineering Minor Beverly Abadines in Applied Physics California State University, San Bernardino Student Alex Acuna Student, Finance Lindenwood University Belleville Illinois United States of America Scholarship Administrative Assistant to the College HACU National Member Colleges & Ms. Angela Acuna President Estrella Mountain Community College Avondale Arizona United States of America Universities Dr. José A. Adames President El Centro College Dallas Texas United States of America Presenter Stephanie Marie Adames‐Anico Student Baylor University Waco Texas United States of America Student Zachary Addington Student, Psychology Transfer Chaffey College Rancho Cucamonga California United States of America Student LaGarius Adside Student, Health Administration Armstrong Atlantic State University Student Higher Education Recruitment Consortium‐ Nancy Aebersold Executive Director HERC Ben Lomond California United States of America Exhibitor Dr. DeBrenna Agbenyiga Vice Provost & Dean, The Graduate School The University of Texas at San Antonio San Antonio Texas United States of America Exhibitor HACU National Member Colleges & Mr. Edward Aguilar Manager San Joaquin Delta College Stockton California United States of America Universities Student, B.A. Sociology with certificate in Ms. Karina Michelle Aguirre gerontology & social service track California State University, San Bernardino San Bernardino California United States of America Student Director of Corporate and Foundation HACU National Member Colleges & Mr. Richard Aguirre Relations Goshen College Goshen Indiana United States of America Universities Oluwapelumi Akiwowo Student, Business Administration Transfer Chaffey College Claremont California United States of America Student HACU National Member Colleges & Jennifer Alanis Director of Diversity and Inclusion Colorado State University–Pueblo Pueblo Colorado United States of America Universities Mr. -

Building Permits Issued Issued Between 04/01/2012 and 04/30/2012

05/01/2012 Building Permits Issued Issued Between 04/01/2012 and 04/30/2012 APNO TYPE PERMIT NAME ADDRESS AND PARCEL INFO CONTRACTOR SF VAL OWNER / OCCUPANT DESCRIPTION 119468 BUILDING MOON HILL PROPERTIES 521 PRINCESS AVE, OWNER/BUILDER 0 0 MOON HILL PROPERTIES L CODCOM L C CODE COMPLIANCE OF AN UNFINISHED SHINGLE ROOF PATIO COVER WITH STUCCO/PAINT TO DETERMINE WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE IN ORDER TO COMPLETE THIS PROJECT. MUST CALL TO SCHEDULE INSPECTION. CONTACT: KEN RAACK OF C R REALTY SERVICES, 702-269-1944 119880 BUILDING 2810 COMMERCE ST, 0 0 COMMERCE-BROOKS CODCOM CODE COMPLIANCE INSPECTION INSPECTION. CONT SAM OR COLLEEN (775) 750-7912 (702) 505-1110 117615 BUILDING AIRGAS WEST-SHADE STRUCTURE 3560 LOSEE RD, 89030-3330 TUMBLEWEED DEVELOPMENT INC 416 4800 AIRGAS-WEST INC COMADD *PROPANE TANK NOT INCLUDED IN THIS PERMIT* INSTALL A NEW 16'X16' (416 SF) METAL SHADE STRUCTURE WITHIN THE ENCLOSED BACKYARD AREA TO SHADE EXISTING OUTDOOR STORAGE BINS. QAA REQUIRED ON ITEMS: X(b) BY NOVA ENGINEERING. SEE APROVED PLANS FOR COMPLETE DETAILS. CONTACT: TOD MARRS OF TUMBLEWEED DEVELOPMENT, 702-568-5400 118601 BUILDING PULIZ - STORAGE RACKS 3830 E CRAIG RD, 89030-7505 XCEL RACK CONTRACTORS 0 79819 A T A A P COMPANY L L C COMADD A/P NAME: PULIZ RECORD MANAGEMENT SERVICES (ORDER TO COMPLY, CASE #286116) INSTALLED HIGH STORAGE RACKS IN EXISTING WAREHOUSE. QAA REQUIRED ON ITEM: X(i) BY AZTECH INSPECTION SERVICES. SEE APPROVED PLANS FOR COMPLETE DETAILS. CONTACT: BOB WHITNEY, 2401 GOLD RIVER ROAD, RANCHO CORDOVA, CA 95670, 916-997-6213, FAX# (916) 635-0366, EMAIL: [email protected] 118650 BUILDING FIRESTONE TIRE-STORAGE RACKING 4640 W ANN RD, 89031- TANAMERA CONSTRUCTION LLC 0 37000 %BRIDGESTONE AMERICAS COMADD TIRE OP S M B C LEASING & FINANCE INC INSTALL TIRE STORAGE RACK. -

THE MYSTERY of IRMA VEP Welcome

per ormances f at the OLD GLOBE ARENA STAGE AT THE JAMES S. COPLEY AUDITORIUM, SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF ART AUGUST 2009 THE MYSTERY OF IRMA VEP Welcome UPCOMING Dear Friends, THE FIRST WIVES CLUB July 17 - Aug. 23, 2009 Welcome to an outrageous Old Globe Theatre evening of murder and mayhem on the moors! The Mystery of Irma Vep is a loving tribute to ❖❖❖ Victorian and gothic mystery, and a tour-de-force for our out- rageously talented actors, Jeffrey SAMMY M. Bender and John Cariani. Sep. 19 - Nov. 1, 2009 Charles Ludlam's enduring Old Globe Theatre masterpiece has had audiences rolling in the aisles for nearly three decades and I know this will be no exception. ❖❖❖ It is certainly the busiest time of the year for The Old Globe. We are presenting a total of five plays on our three stages. The Broadway- bound world premiere of The First Wives Club is currently playing in T H E SAVA N N A H the Old Globe Theatre. Music legends Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier DISPUTATION and Eddie Holland (Stop! In The Name of Love) have fashioned an Sep. 26 - Nov. 1, 2009 infectious score for this musical based on the popular film and book. The Old Globe Arena Stage at Get your tickets soon so you can say, “I saw it here first!” the James S. Copley Auditorium, The centerpiece of our summer season, as it has been for 75 years, is San Diego Museum of Art our Shakespeare Festival — currently in full swing with Twelfth Night, Cyrano de Bergerac and Coriolanus in repertory in the outdoor Festival Theatre. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

First Notice

FINAL NOTICE UNCLAIMED FUNDS FROM BANCO POPULAR DE PUERTO RICO & POPULAR INC. The persons whose names appear below, are entitled to claim unclaimed as of June 30, 2021. This report includes amounts Unclaimed funds will be payable by Banco Popular de Puerto from Banco Popular de Puerto Rico and Popular Inc., the with balances of one hundred ($100) dollars or more not Rico and Popular Inc. until November 30th to the persons with amounts corresponding to funds unclaimed or abandoned for published in this notice. A copy of the report including all right to collect them. On December 10, 2021, all unclaimed more than five (5) years. The names that appear in this notice amounts will be available for public inspection in all Popular funds will be delivered to the Office of the Commissioner and are only those of the owners of accounts with balances of less Auto and Banco Popular de Puerto Rico branches. from the date of delivery all responsibility of Banco Popular de than one hundred ($100) dollars. A report has been sent to the Furthermore, it will be available in our website Puerto and Popular Inc. in relation to said funds will cease. Any Office of the Commissioner of Financial Institutions (the “Office www.popular.com. There are no publication fees against the claim after November 30th should be filed through the Office of of the Commissioner”) for Banco Popular de Puerto Rico and funds published in this notice. the Commissioner. Popular Inc., in compliance with applicable laws for amounts DEPOSIT ACCOUNTS ALMODOVAR GARCIA ISRAEL A SAN JUAN -

(MARAD) Listing of Small Vessel Waivers Granted 2005-2017

Description of document: Department of Transportation Maritime Administration (MARAD) listing of small vessel waivers granted for coastwide trade, 2005-2017 Requested date: 19-May-2017 Release date: 30-May-2017 Posted date: 14-January-2019 Source of document: FOIA Request Division of Legislation and Regulations U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Administration Second Floor, West Building 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE, W24-233 Washington, DC 20590 Fax: (202) 366-7485 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. Second Floor, West Building W24-220 Mailstop #4 Washington, D.C. -

Poemas Del Alma

Antología de Un Rincon Infantil Antología de Un Rincon Infantil Dedicatoria A todos los niños del mundo que juegan con sus sueños y van por la vida con su alma olorosa a caramelos. Página 2/874 Antología de Un Rincon Infantil Agradecimiento A todos aquellos que al leer estos poemas pequeñitos, sientan una alegría grandototota y se sientan felices. Página 3/874 Antología de Un Rincon Infantil Sobre el autor Soy alguien que siempre lleva un niño dentro de mí, y que aunque crecí, él nunca me abandonó, ni yo a él. Página 4/874 Antología de Un Rincon Infantil índice Hoja Seca Ciempiés Mi moneda Versos a una Mariquita Gotita de agua Estrellita de mar Cosas de abuela Sueño de poeta La Biblia Los Bomberos La letra ?S? El triciclo Contando cuentos Pajarito ¡ Gracias ! Vestir como papá ¡Silencio! Promesa estudiantil Trabalenguas El Borrador Dibujando a mi papá Siembra Quiero ser Doctor Página 5/874 Antología de Un Rincon Infantil El tobogán Mariposas Amistad Contaminación Versos a mi cometa La tina La patineta del pollito Los regalos de mi tía Tocando piano En casa hay un libro Léeme un cuento Amistad con diferencias Casa de lata El agua que corre El recreo La Bandera Dibujando El Barbero La rana enamorada La vaca Luna sin piernas Sumando Señora Jirafa Cumpleaños de un amigo Saluda, tortuga Página 6/874 Antología de Un Rincon Infantil Domingo de cine El puente caído Mascota sin raza La Montaña Salta, salta La amiga abeja Mudanza Señora oruga Vuela Mariposa La Princesa y sus vestidos Vigilante del camino Pasando de grado Aprendí a leer Carta de -

FY2009 Annual Listing

2008 2009 Annual Listing Exhibitions PUBLICATIONS Acquisitions GIFTS TO THE ANNUAL FUND Membership SPECIAL PROJECTS Donors to the Collection 2008 2009 Exhibitions at MoMA Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at The Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London. Photo © Frederick Charles, fcharles.com Exhibitions at MoMA Book/Shelf Bernd and Hilla Becher: Home Delivery: Fabricating the Through July 7, 2008 Landscape/Typology Modern Dwelling Organized by Christophe Cherix, Through August 25, 2008 July 20–October 20, 2008 Curator, Department of Prints Organized by Peter Galassi, Chief Organized by Barry Bergdoll, The and Illustrated Books. Curator of Photography. Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Peter Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing Dalí: Painting and Film Christensen, Curatorial Assistant, Through July 7, 2008 Through September 15, 2008 Department of Architecture and Organized by Connie Butler, Organized by Jodi Hauptman, Design. The Robert Lehman Foundation Curator, Department of Drawings. Chief Curator of Drawings. Young Architects Program 2008 Jazz Score July 20–October 20, 2008 Multiplex: Directions in Art, Through September 17, 2008 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, 1970 to Now Organized by Ron Magliozzi, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Assistant Curator, and Joshua Design. Organized by Deborah Wye, Siegel, Associate Curator, The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Department of Film. Dreamland: Architectural Chief Curator of Prints and Experiments since the 1970s Illustrated Books. George Lois: The Esquire Covers July 23, 2008–March 16, 2009 Through March 31, 2009 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, Projects 87: Sigalit Landau Organized by Christian Larsen, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Curatorial Assistant, Research Design. -

2006 Tulare County Kids of Character Student Name Pillar School Joann Abad Responsibility Buena Vista Elementary School, Tulare Alfredo Abarca Respect John J

2006 Tulare County Kids of Character Student Name Pillar School Joann Abad Responsibility Buena Vista Elementary School, Tulare Alfredo Abarca Respect John J. Doyle Elementary School, Porterville Ariel Abasta Trustworthiness Roche Avenue Elementary School, Porterville Victoria Abbott Caring Tulare Western High School, Tulare Mosa Abdulla Respect Los Robles Elementary School, Porterville Nisar Abdulla Citizenship Los Robles Elementary School, Porterville Tureye Abdulla Citizenship Los Robles Elementary School, Porterville Abraham Able Respect Frank Kohn Elementary School, Tulare Bodhi Abourezk Caring Three Rivers Elementary School, Three Rivers Cody Abreu Caring Monte Vista Elementary School, Porterville Zack Acencio Responsibility Summit Charter Academy, Porterville Angel Acevedo Caring Olive Street Elementary School, Porterville Antonio Acevedo Citizenship John J. Doyle Elementary School, Porterville Britthie Acevedo Caring John J. Doyle Elementary School, Porterville Catalina Acevedo Respect Burton Elementary School, Porterville Daniel Acevedo Caring John J. Doyle Elementary School, Porterville Fabiola Acevedo Trustworthiness Lincoln Elementary School, Lindsay Gerardo Acevedo Responsibility Santa Fe Elementary School, Porterville Isamar Acevedo Trustworthiness Monte Vista Elementary School, Porterville Gypsy Aceves Responsibility Monte Vista Elementary School, Porterville Dabne Acosta Responsibility Waukena Elementary School, Waukena Jasmin Acosta Caring Palo Verde Elementary School, Tulare Juan Acosta Citizenship Buena Vista Elementary