Space Security 2004 Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIGINT: the Mission Cubesats Are Made for a Small Country’S Perspective

Naval Research Laboratory 22 June 1960 SIGINT: The Mission CubeSats are Made For A Small Country’s Perspective 32nd Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites 1 ISIS - Innovative Solutions In Space Vertically Integrated Small Satellite Company SATELLITE CUBESAT LAUNCH SERVICES R&D SERVICES SOLUTIONS PRODUCTS 2 SIGINT – ELINT – Spectrum Monitoring SIGINT SpectrumCOMINT Monitoring ELINT FISINT/TELINT TECHNICAL OPERATIONAL • Discover new systems • Location • Details about emissions • Schedule • Performance estimation • Movement • ECM development • Warning 3 Spectrum Monitoring Causes of Interference Source: Eutelsat briefing to the ITU (2013) 4 Miniturization 5 ELINT: Single-Satellite Solution Lotos-S/Pion-NKS 8 - 12 m Images courtesy of RussianSpaceWeb 6 ELINT: Direction Finding Direction of Arrival/Angle of Arrival 7 Fundamental Limits Why the Shrink-Ray Won’t Work Size has effect on direction finding accuracy because of: • Antenna gain (i.e. SNR) • Number of array elements that can be placed • Array element spacing A 6U-face of CubeSat offers very limited real estate Images courtesy of NASA 8 BRIK-II Royal Netherlannds Air Force 9 ELINT: Multi-Satellite Solution Naval Ocean Surveillance System Picture by John C. Murphy 10 Capacité de Renseignement Electromagnétique Spatiale (CERES) 781 M€ Essaim 216 M€ 2004 Elisa 115 M€ 2007 2009 2011 CERES 450 M€ 2013 2015 2020 Images courtesy of CNES 11 Miniturization through Distribution Opening Up The Trade Space Number of satellites in orbit Image courtesy of the Science and Technology Policy Institute 12 Radio Astronomy An Intransparent Affair 13 Orbiting Low Frequency Antennas for Radio Astronomy < 100 km > 50 satellites = 0.006° (30 MHz) 14 Maturing CubeSats for ELINT/Spectrum Monitoring & Astronomy Development Areas Station-Keeping ISL & Synchronization 2-100 Satellites Relative Position Knowledge From A. -

Space Debris

IADC-11-04 April 2013 Space Debris IADC Assessment Report for 2010 Issued by the IADC Steering Group Table of Contents 1. Foreword .......................................................................... 1 2. IADC Highlights ................................................................ 2 3. Space Debris Activities in the United Nations ................... 4 4. Earth Satellite Population .................................................. 6 5. Satellite Launches, Reentries and Retirements ................ 10 6. Satellite Fragmentations ................................................... 15 7. Collision Avoidance .......................................................... 17 8. Orbital Debris Removal ..................................................... 18 9. Major Meetings Addressing Space Debris ........................ 20 Appendix: Satellite Break-ups, 2000-2010 ............................ 22 IADC Assessment Report for 2010 i Acronyms ADR Active Debris Removal ASI Italian Space Agency CNES Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (France) CNSA China National Space Agency CSA Canadian Space Agency COPUOS Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, United Nations DLR German Aerospace Center ESA European Space Agency GEO Geosynchronous Orbit region (region near 35,786 km altitude where the orbital period of a satellite matches that of the rotation rate of the Earth) IADC Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee ISRO Indian Space Research Organization ISS International Space Station JAXA Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency LEO Low -

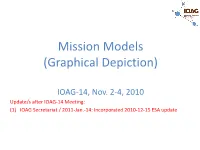

Mission Model (Aggregate)

Mission Models (Graphical Depiction) IOAG-14, Nov. 2-4, 2010 Update/s after IOAG-14 Meeting: (1) IOAG Secretariat / 2011-Jan.-14: Incorporated 2010-12-15 ESA update Earth Missions (1) 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 COSMO –SM1 COSMO –SM2 ASI COSMO –SM3 COSMO –SM4 AGI MIOSAT PRISMA SPOT HELIOS 2010 TELECOM-2 Legend Green – In operation JASON Light green – Potential extension Blue – In development DEMETER TARANIS Light Blue – Potential extension Yellow – Proposed ESSAIM MICROSCOPE Light Yellow – Proposed extension CNES PARASOL MERLIN Note: Color fade to white indicates End Date unknown CALIPSO COROT CERES SMOS CSO-MUSIS (terminate 2028, potentially extend to 2030) PICARD MICROCARB (*) No dates provided Earth Missions (2) 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 BIR DEOS Legend Green – In operation GR1/ GR2 ENMAP Light green – Potential extension Blue – In development SB1/SB2 Light Blue – Potential extension Yellow – Proposed DLR TerraSAR-X H2SAT* Light Yellow – Proposed extension TET Asteroiden Finder* Note: Color fade to white indicates End Date unknown TanDEM-X PRISMA 2010 (*) No dates provided Earth Missions (3) 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 ERS 2 ADM-AEOLUS ENVISAT Sentinel 1B Extends to Oct. 2026 CRYOSAT 2 Sentinel 2B Extends to Jun. 2027 GOCE Earth Case Swarm Sentinel 1A Sentinel 2A Sentinel 3A ESA 2010 Sentinel 3B Extends to Aug. 2027 MSG MSG METOP METOP ARTEMIS GALILEO Legend Green – In operation -

A B 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

A B 1 Name of Satellite, Alternate Names Country of Operator/Owner 2 AcrimSat (Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor) USA 3 Afristar USA 4 Agila 2 (Mabuhay 1) Philippines 5 Akebono (EXOS-D) Japan 6 ALOS (Advanced Land Observing Satellite; Daichi) Japan 7 Alsat-1 Algeria 8 Amazonas Brazil 9 AMC-1 (Americom 1, GE-1) USA 10 AMC-10 (Americom-10, GE 10) USA 11 AMC-11 (Americom-11, GE 11) USA 12 AMC-12 (Americom 12, Worldsat 2) USA 13 AMC-15 (Americom-15) USA 14 AMC-16 (Americom-16) USA 15 AMC-18 (Americom 18) USA 16 AMC-2 (Americom 2, GE-2) USA 17 AMC-23 (Worldsat 3) USA 18 AMC-3 (Americom 3, GE-3) USA 19 AMC-4 (Americom-4, GE-4) USA 20 AMC-5 (Americom-5, GE-5) USA 21 AMC-6 (Americom-6, GE-6) USA 22 AMC-7 (Americom-7, GE-7) USA 23 AMC-8 (Americom-8, GE-8, Aurora 3) USA 24 AMC-9 (Americom 9) USA 25 Amos 1 Israel 26 Amos 2 Israel 27 Amsat-Echo (Oscar 51, AO-51) USA 28 Amsat-Oscar 7 (AO-7) USA 29 Anik F1 Canada 30 Anik F1R Canada 31 Anik F2 Canada 32 Apstar 1 China (PR) 33 Apstar 1A (Apstar 3) China (PR) 34 Apstar 2R (Telstar 10) China (PR) 35 Apstar 6 China (PR) C D 1 Operator/Owner Users 2 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Government 3 WorldSpace Corp. Commercial 4 Mabuhay Philippines Satellite Corp. Commercial 5 Institute of Space and Aeronautical Science, University of Tokyo Civilian Research 6 Earth Observation Research and Application Center/JAXA Japan 7 Centre National des Techniques Spatiales (CNTS) Government 8 Hispamar (subsidiary of Hispasat - Spain) Commercial 9 SES Americom (SES Global) Commercial -

Overview on 2010 Space Debris Activities in France

OVERVIEW ON 2010 SPACE DEBRIS ACTIVITIES IN FRANCE F.ALBY SUMMARY ■Atmospheric reentries ■End of life operations ■Collision risk monitoring ■French Space Act ■Space debris measurements ■Important meetings UN-COPUOS, 48th session of the STSC, 7-18 February 2011, Vienna 1-ATMOSPHERIC REENTRIES ■2 French registered objects reentered into the atmosphere in 2010: Identification Launch date Description Reentry date 2009-058-D 29 Oct 2009 Ariane 5 (V192) 9 Sept 2010 SYLDA 2001-029-D 12 July 2001 Ariane 5 (V142) 6 Oct 2010 SYLDA UN-COPUOS, 48th session of the STSC, 7-18 February 2011, Vienna 2-END OF LIFE OPERATIONS (1/3) ■4 « ESSAIM » satellites launched December 18, 2004, Ariane 5 ■« Myriade » platform: ~120 kg, formation flying ■Quasi heliosynchroneous orbit around 700 km altitude ■Mission: characterization of the electromagnetic environment ■Development ASTRIUM + CNES ■Operated by CNES on behalf of DGA UN-COPUOS, 48th session of the STSC, 7-18 February 2011, Vienna 2-END OF LIFE OPERATIONS (2/3) ■Essaim end of life operations in September and October 2010 ■1st step: altitude lowering in order to: reduce the orbital lifetime empty the tanks manage the collision risks between the 4 satellites ■2nd step: electrical passivation Battery discharge Satellites swith-off ■Final orbit: the 4 satellites are compliant with the 25-year rule UN-COPUOS, 48th session of the STSC, 7-18 February 2011, Vienna 2-END OF LIFE OPERATIONS (3/3) ■ EUTELSAT W2 built by Alcatel Space ■ Platform Spacebus 3000: 3t ■ Launched October 1998 by Eutelsat IGO ■ Decommissioned -

X-Band Transmission Evolution Towards DVB-S2

X-band transmission evolution towards DVB-S2 for Small Satellites Miguel Angel Fernandez, Anis Latiri, Gabrielle Michaud – SYRLINKS Clément Dudal, Jean-Luc Issler – CNES SSC 2016 – LOGAN | August 10, 2016 Outline About Syrlinks Flight proven X-band transmitter DVB-S2 implementation High Data Rate Transmitter evolutions SYRLINKS – CNES Small Satellite Conference 2016 2 About Syrlinks Flight Proven X-band Transmitter DVB-S2 Implementation High Data Rate Transmitter Evolutions SYRLINKS – CNES Small Satellite Conference 2016 3 About Syrlinks… . Advanced and cost-effective radio-communication manufacturer . Focuses on advanced, compact, & high reliable radios, for harsh environments . Designs, develops of communication systems in radio navigation & geolocation . Partnership with CNES and ESA since 1997 (Rosetta) * * PARIS . 200 cumulated years in orbit, with 100% reliability RENNES . Pioneer in the use of qualified active COTS . Large space portfolio for LEO missions up to 10 years in orbit, especially based on CLASS 3 ECC-Q-ST-60C design SYRLINKS – CNES Small Satellite Conference 2016 4 2014: EWC30 & 29 CLASS 3 ECSS-Q- Some Milestones… ST-60-C Radios 2012: G-SPHERE-S 2013: EWC27 & 31 GNSS Receiver Nano Radios 2010: EWC22/24/28 2010: EWC20 X Band HDR TM L Band Transmitter 2011: GREAT2 (ESA) GaN Reliability And Technology Transfer initiative 1997: EWC15 2004-2013: EWC15 S Band “ISL” S Band TT&C MYRIADE: CNES/ AIRBUS D&S/ TAS MYRIADE Evolutions ADS/CNES/TAS platform 2004: Rosetta/Philae. Demeter, Essaim (4), PROBA-V: 2013 2013: SARAL Microscope: -

Faszination Raumfahrt Erleben! Viele Von Uns Waren Noch Gar Nicht Auf Der Welt, Da War Der Mensch Schon Auf Dem Mond

Der Verein zur Förderung der Raumfahrt VFR e.V. präsentiert: Das Raumfahrtjahr 2004 kompetent und spannend dokumentiert von Eugen Reichl u.a. Autoren 22.06.: SpaceShipOne erreicht den Weltraum 01.07. :Raumsonde Cassini durchquert die Saturnringe 10.05.: Erster Flug des PHOENIX 04.10. Brian Binnie holt mit dem 2. Wettbewerbsflug den X-Prize 04.01.: „Spirit“ erfolgreich auf dem Mars gelandet Mai: „Opportunity“ erforscht den Endurance Krater. 09.09. Bergung von Genesis scheitert 14.01.: US-Präsident Bush verkündet Amerikas neue Raumfahrt-Initiative FASZINATION RAUMFAH2004RspacexpressT ER raumfahrtchronikLEBEN1 JAHR FÜR JAHR: AKTUELLE RAUMFAHRTGESCHICHTE AUS ERSTER HAND! Die faszinierende Welt der Raumfahrt im einzigen deutschsprachigen Raumfahrtjahr- buch. Rückblick und Ausblick. Nehmen Sie teil am spannendsten Abenteuer unserer Zeit... Jedes Jahrbuch gibt es als kostenloses eBook und auch als hochwertige Printausgabe – im Vergleich zum Selber-Ausdrucken eine günstige, und vor allem attraktive Alternative. Downloads und Buchbestellung finden Sie auf JAHR FÜR JAHR: AKTUELLE RAUMFAHRTGESCHICHTE AUS ERSTER HAND! eBook Edition, Juli 2007 Copyright © by VFR e.V. Alle Rechte vorbehalten Initiator: Verein zur Förderung der Raumfahrt VFR e.V. (www.vfr.de) Lektorat: Heimo Gnilka und Hans Rauch Layout & Satz: Stefan Schiessl, Dachau (www.schiessldesign.de) ISBN: 3-00-015723-9 2004 spacexpress raumfahrtchronik 3 inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ________________________________5 Mut zur Lücke bei der Cassini/Huygens-Mission (Eugen Reichl) _________________________114 -

Index of Astronomia Nova

Index of Astronomia Nova Index of Astronomia Nova. M. Capderou, Handbook of Satellite Orbits: From Kepler to GPS, 883 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-03416-4, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Bibliography Books are classified in sections according to the main themes covered in this work, and arranged chronologically within each section. General Mechanics and Geodesy 1. H. Goldstein. Classical Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, Mass., 1956 2. L. Landau & E. Lifchitz. Mechanics (Course of Theoretical Physics),Vol.1, Mir, Moscow, 1966, Butterworth–Heinemann 3rd edn., 1976 3. W.M. Kaula. Theory of Satellite Geodesy, Blaisdell Publ., Waltham, Mass., 1966 4. J.-J. Levallois. G´eod´esie g´en´erale, Vols. 1, 2, 3, Eyrolles, Paris, 1969, 1970 5. J.-J. Levallois & J. Kovalevsky. G´eod´esie g´en´erale,Vol.4:G´eod´esie spatiale, Eyrolles, Paris, 1970 6. G. Bomford. Geodesy, 4th edn., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1980 7. J.-C. Husson, A. Cazenave, J.-F. Minster (Eds.). Internal Geophysics and Space, CNES/Cepadues-Editions, Toulouse, 1985 8. V.I. Arnold. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (60), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1989 9. W. Torge. Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991 10. G. Seeber. Satellite Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993 11. E.W. Grafarend, F.W. Krumm, V.S. Schwarze (Eds.). Geodesy: The Challenge of the 3rd Millennium, Springer, Berlin, 2003 12. H. Stephani. Relativity: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity,Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004 13. G. Schubert (Ed.). Treatise on Geodephysics,Vol.3:Geodesy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2007 14. D.D. McCarthy, P.K. -

Large Volume Production of Lithium-Ion Battery Units for the Space Industry

Large Volume Production of Lithium-ion Battery Units for the Space Industry November 2015 David Curzon – Product Line Manager Kevin Schrantz - Director, Space & Medical Introduction Presenting • EnerSys’s solution to a developing market demand Challenge • High volume production for large satellite constellations Discuss • Meeting the market demands for Li-ion space batteries • Challenges to be considered • Solutions • Is this a healthy progression for the industry? EnerSys Proprietary © 2015 EnerSys. Export or re-export of information contained herein may be subject to restrictions and requirements of U.S. export laws and regulations and may require 2 advance authorization from the U.S. government. Industry Demand The emerging large constellation market is pushing for higher volume, lower cost batteries with demanding schedules. Questions the industry faces include what does this new demand mean, what will be the long term affects, what pressure will be passed onto suppliers, and will the risk tolerance change in proportion? If a higher risk tolerance is accepted for some missions, will the industry turn to commercially available products (such as commercial battery packs or batteries) qualified & characterized for space? As an industry, this market is asking all of us to look at methods for increasing throughput, design for manufacturability, modularity, and common systems. EnerSys Proprietary © 2015 EnerSys. Export or re-export of information contained herein may be subject to restrictions and requirements of U.S. export laws and regulations and may require 3 advance authorization from the U.S. government. Lithium-ion Battery Market Evolution Lithium-ion implementation has steadily grown Power consumption trending upwards - driving for higher performance, cells, batteries & modules Number of different applications has increased year on year Proba – Longest EMU – Manned Applications SDO – Interplanetary TerraSAR – Earth/Remote serving Li-ion in Science Support Sensing Space (14 yrs. -

Space Security 2004 V2

Space Security 2004 Space “I know of no similar yearly baseline of what is happening in space. The Index is a valuable tool for informing much-needed global discussions of how best to achieve space security.” Professor John M. Logsdon Director, Space Policy Institute, Elliott School of International Affair, George Washington University “Space Security 2004 is a salutary reminder of how dependent the world has become on space- based systems for both commercial and military use. The overcrowding of both orbits and frequencies needs international co-operation, but the book highlights some worrying security trends. We cannot leave control of space to any one nation, and international policy makers need to read this excellent survey to understand the dangers.” Air Marshal Lord Garden UK Liberal Democrat Defence Spokesman & Former UK Assistant Chief of the Defence Staff Space Security “Satellites are critical for national security. Space Security 2004 is a comprehensive analysis of the activities of space powers and how they are perceived to affect the security of these important assets and their environment. While all may not agree with these perceptions it is 2004 essential that space professionals and political leaders understand them. This is an important contribution towards that goal.” Brigadier General Simon P. Worden, United States Air Force (Ret.) Research Professor of Astronomy, Planetary Sciences and Optical Sciences, University of Arizona “In a single source, this publication provides a comprehensive view of the latest developments in space, and the trends that are influencing space security policies. As an annual exercise, the review is likely to play a key role in the emerging and increasingly important debate on space security. -

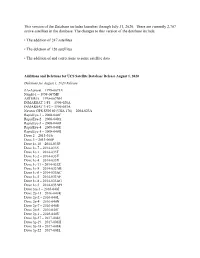

This Version of the Database Includes Launches Through July 31, 2020

This version of the Database includes launches through July 31, 2020. There are currently 2,787 active satellites in the database. The changes to this version of the database include: • The addition of 247 satellites • The deletion of 126 satellites • The addition of and corrections to some satellite data Additions and Deletions for UCS Satellite Database Release August 1, 2020 Deletions for August 1, 2020 Release ZA-Aerosat – 1998-067LU Nsight-1 – 1998-067MF ASTERIA – 1998-067NH INMARSAT 3-F1 – 1996-020A INMARSAT 3-F2 – 1996-053A Navstar GPS SVN 60 (USA 178) – 2004-023A RapidEye-1 – 2008-040C RapidEye-2 – 2008-040A RapidEye-3 – 2008-040D RapidEye-4 – 2008-040E RapidEye-5 – 2008-040B Dove 2 – 2013-015c Dove 3 – 2013-066P Dove 1c-10 – 2014-033P Dove 1c-7 – 2014-033S Dove 1c-1 – 2014-033T Dove 1c-2 – 2014-033V Dove 1c-4 – 2014-033X Dove 1c-11 – 2014-033Z Dove 1c-9 – 2014-033AB Dove 1c-6 – 2014-033AC Dove 1c-5 – 2014-033AE Dove 1c-8 – 2014-033AG Dove 1c-3 – 2014-033AH Dove 3m-1 – 2016-040J Dove 2p-11 – 2016-040K Dove 2p-2 – 2016-040L Dove 2p-4 – 2016-040N Dove 2p-7 – 2016-040S Dove 2p-5 – 2016-040T Dove 2p-1 – 2016-040U Dove 3p-37 – 2017-008F Dove 3p-19 – 2017-008H Dove 3p-18 – 2017-008K Dove 3p-22 – 2017-008L Dove 3p-21 – 2017-008M Dove 3p-28 – 2017-008N Dove 3p-26 – 2017-008P Dove 3p-17 – 2017-008Q Dove 3p-27 – 2017-008R Dove 3p-25 – 2017-008S Dove 3p-1 – 2017-008V Dove 3p-6 – 2017-008X Dove 3p-7 – 2017-008Y Dove 3p-5 – 2017-008Z Dove 3p-9 – 2017-008AB Dove 3p-10 – 2017-008AC Dove 3p-75 – 2017-008AH Dove 3p-73 – 2017-008AK Dove 3p-36 – -

2004 Commercial Space Transportation Year in Review Draft

2004 YEAR IN REVIEW INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION The Commercial Space Transportation: 2004 Launch, LLC. The APStar 5 launch was con- Year in Review summarizes U.S. and interna- sidered a partial failure because the Zenit’s tional launch activities for calendar year 2004 upper stage shut down prematurely, placing and provides a historical look at the past five the satellite in a lower-than-intended orbit, years of commercial launch activities. but the spacecraft was able to reach its desti- nation in GEO using its onboard thrusters The Federal Aviation Administration’s without reducing its on-orbit lifetime. Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA/AST) licensed nine commercial orbital Overall, 15 commercial orbital launches launches and five suborbital launches in occurred worldwide in 2004, representing 28 2004. percent of the 54 total launches for the year. The 15 commercial launches represent a 12 Of the nine orbital licensed launches, six percent decrease from 2003. FAA/AST- were of U.S.-built vehicles. International licensed orbital launch activity accounted for Launch Services (ILS) launched three Atlas 60 percent of the worldwide commercial 2AS boosters, carrying the AMC 10, AMC launch market in 2004. Russia conducted five 11, and Superbird 6 communications satel- commercial launch campaigns, bringing its lites; these launches were the last commercial commercial launch market share to about 33 missions for the Atlas 2 family of vehicles, percent for the year. Arianespace conducted which ILS and Lockheed Martin retired in only a single commercial launch in 2004. 2004. ILS also launched the MBSAT 1 and AMC 16 communications satellites on an FAA/AST issued its first-ever suborbital Atlas 3A and an Atlas 5 521, respectively.