Armenia's Election Aftermath: Few Street Protests, but the New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Economic Monitor Armenia

ECONOMIC MONITOR ARMENIA Issue 1 | October 2019 [updated] Overview • Economic growth in Q1-19 (7.2%) and Q2-19 (6.5%) significantly higher than expected • Budget surplus in 7M2019 due to high revenues & under-execution of capital expenditures • Inflation forecast for 2019 at 2.1%; low inflation key ingredient of macroeconomic stability ➢ Stable macroeconomic situation • Significant jump of current account deficit in 2018 to 9.4% of GDP; quite high • FDI only at 2.1% in 2018, not sufficient for financing the current account deficit • Imports (+21.4%) increased much stronger than exports (+7.8%) in 2018 ➢ Export promotion and FDI attraction key for external stability • Mid-term fiscal consolidation: budget deficit ≈ 2% and central gov debt < 50% of GDP • At the same time: lower tax rates and higher expenditures on social & investment planned ➢ Ambitious mid-term fiscal plans Special topics • Recent political events • Fight against corruption • Energy: challenges and government plans • FDI attraction: focus on most promising target groups and institutional framework Basic indicators Armenia Azerbaijan Georgia Belarus Ukraine Russia GDP, USD bn 13.1 45.2 17.2 61.0 134.9 1,610.4 GDP/capita, USD 4,381 4,498 4,661 6,477 3,221 11,191 Population, m 3.0 10.0 3.7 9.4 41.9 143.9 Source: IMF WEO from April 2019; Forecast 2019 Trade structure Exports Imports EU 28% | Russia 28% | Switzerland 14% | Others 30% EU 23% | Russia 25% | China 13% | Others 39% Others Copper ores Others Machinery/ 19% 22% 24% Electrical Vegetable and 19% animal products Mineral 6% Motor vehicles Metals products 6% Textiles 12% 14% 10% Textiles Gold 6% 7% Metals Animal and Spirits 7% vegetable 8% Mineral products Tobacco Chemicals products (excl. -

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Armenia Parliamentary Elections, 2 April 2017

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Armenia Parliamentary Elections, 2 April 2017 INTERIM REPORT 21 February – 14 March 2017 17 March 2017 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On 29 December 2016, the president of the Republic of Armenia called parliamentary elections for 2 April. Following a referendum held on 6 December 2015, the Constitution was amended changing Armenia’s political system from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary one. These will be the first elections held under a new proportional electoral system. • Parliamentary elections are regulated by a comprehensive but complex legal framework, which was significantly amended in 2016 through an inclusive reform process that was seen by most OSCE/ODIHR EOM interlocutors as a step forward in building overall confidence in the electoral process. A number of previous OSCE/ODIHR recommendations have been addressed. Civil society organizations were initially involved in the discussions of the draft Electoral Code, but did not endorse the final text, as their calls to ease restrictions on citizen observers were not addressed. • The elections are administered by a three-tiered system, comprising the Central Election Commission (CEC), 38 Territorial Election Commissions (TECs), and 2,009 Precinct Election Commissions (PECs). The CEC regularly holds open sessions and publishes its decisions on its website. The PECs were formed by the TECs on 11 March. Some OSCE/ODIHR EOM interlocutors expressed concerns about PECs capacity to deal with the new voting procedures. • Voter registration is passive and based on the population register. OSCE/ODIHR EOM interlocutors generally assessed the accuracy of the voter list positively. -

Download Strategeast Westernization Report 2019

ABOUT STRATEGEAST StrategEast is a strategic center whose goal is to create closer working ties between political and business leaders in the former Soviet countries outside of Russia and their peers in the U.S. And Western Europe. StrategEast believes nations from the former Soviet Union share a heritage that has resulted in common obstacles to the formation of stable, effi cient, market-oriented democracies. We hope to appeal to political, business, and academic leaders in post-Soviet countries and the West, helping them better understand one another, communicate across borders, and collaborate to support real change. Our work is focused on the 14 former Soviet states outside of Russia. This post-Soviet, non-Russia (PSNR) region includes: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. StrategEast focuses on six key issue areas that are especially infl uential to the transition to Western political and economic systems: fi ghting corruption, implementing a Western code of business conduct within a post-Soviet business environment, modernizing infrastructure, promoting independent LEARN MORE press and civil society, energy transparency, and leadership impact. AT OUR WEBSITE: www.StrategEast.org StrategEast is a registered 501c3 based in the United States. THIS REPORT Ravshan Abdullaev Salome Minesashvili Maili Vilson WAS WRITTEN BY: Ilvija Bruģe Parviz Mullojanov Andrei Yahorau Tamerlan Ibraimov Boris Navasardian Yuliy Yusupov Gubad Ibadoghlu Sergiy Solodkyy Zharmukhamed Zardykhan Leonid Litra Dovilė Šukytė © 2019 StrategEast. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-578-46255-4 “StrategEast Westernization Report 2019” is available on our website: www.StrategEast.org StrategEast 1900 K Street, NW Suite 100 Washington, D. -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 98, 6 October 2017 2

No. 98 6 October 2017 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html ARMENIAN ELECTIONS Special Editor: Milena Baghdasaryan ■■Introduction by the Special Editor 2 ■■Before the Voting Day: The Impact of Patron–Client Relations and Related Violations on Elections in Armenia 2 By Milena Baghdasaryan ■■The Role of Civil Society Observation Missions in Democratization Processes in Armenia 8 By Armen Grigoryan (Transparency International Anticorruption Center, Armenia) ■■Some of the Major Challenges of the Electoral System in the Republic of Armenia 12 By Tigran Yegoryan (NGO “Europe in Law Association”, Yerevan) Research Centre Center Caucasus Research Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies East European Studies Resource Centers Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 98, 6 October 2017 2 Introduction by the Special Editor Parliamentary elections have become the central event in Armenia’s political life as the constitutional referendum of 2015 transformed the country into a parliamentary republic. The first parliamentary elections after the referendum were held on April 2, 2017; they were soon followed by municipal elections in Armenia’s capital on May 14, 2017. During the national elections several Armenian NGOs organized an unprecedentedly comprehensive observation mission, by jointly having observers in about 87% of the republic’s polling stations, while the oppositional Yelk alliance claims to have been able to send proxies to all of Yerevan’s polling stations during the municipal elections. However, the public discourse in Armenia holds that the core of violations took place outside the polling stations. -

5195E05d4.Pdf

ILGA-Europe in brief ILGA-Europe is the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Intersex Association. ILGA-Europe works for equality and human rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans & intersex (LGBTI) people at European level. ILGA-Europe is an international non-governmental umbrella organisation bringing together 408 organisations from 45 out of 49 European countries. ILGA-Europe was established as a separate region of ILGA and an independent legal entity in 1996. ILGA was established in 1978. ILGA-Europe advocates for human rights and equality for LGBTI people at European level organisations such as the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). ILGA-Europe strengthens the European LGBTI movement by providing trainings and support to its member organisations and other LGBTI groups on advocacy, fundraising, organisational development and communications. ILGA-Europe has its office in Brussels and employs 12 people. Since 1997 ILGA-Europe enjoys participative status at the Council of Europe. Since 2001 ILGA-Europe receives its largest funding from the European Commission. Since 2006 ILGA-Europe enjoys consultative status at the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC) and advocates for equality and human rights of LGBTI people also at the UN level. ILGA-Europe Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe 2013 This Review covers the period of January -

Final Report

RA Parliamentary Elections April 2, 2017 “Independent Observer” Public Alliance Final Report 2017 RA Parliamentary Elections April 2, 2017 “Independent Observer” Public Alliance Final Report 2017 Editor Artur Sakunts Authors Vardine Grigoryan Anush Hambaryan Daniel Ioannisyan Artur Harutyunyan The observation mission was carried out with the financial assistance of the Council of Europe and European Union, European Endowment for Democracy, Open Society Foundations - Armenia, Sigrid Rausing Trust, Czech Embassy in Armenia and Norwegian Helsinki Committee. The report was produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and Council of Europe. The “Long-term Electoral Assistance to the Election Related Stakeholders in Armenia” Project is funded within European Union and Council of Europe Programmatic Co-operation Framework in the Eastern Partnership Countries for 2015-2017. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to represent the official opinions of the funding organizations. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology ........................................................................................................ 8 Legislative Framework and Political Context ................................................. 10 Organization of Elections .................................................................................. 18 Electoral Commissions................................................................................... -

Evaluation of the April 2, 2017 Parliamentary Elections In

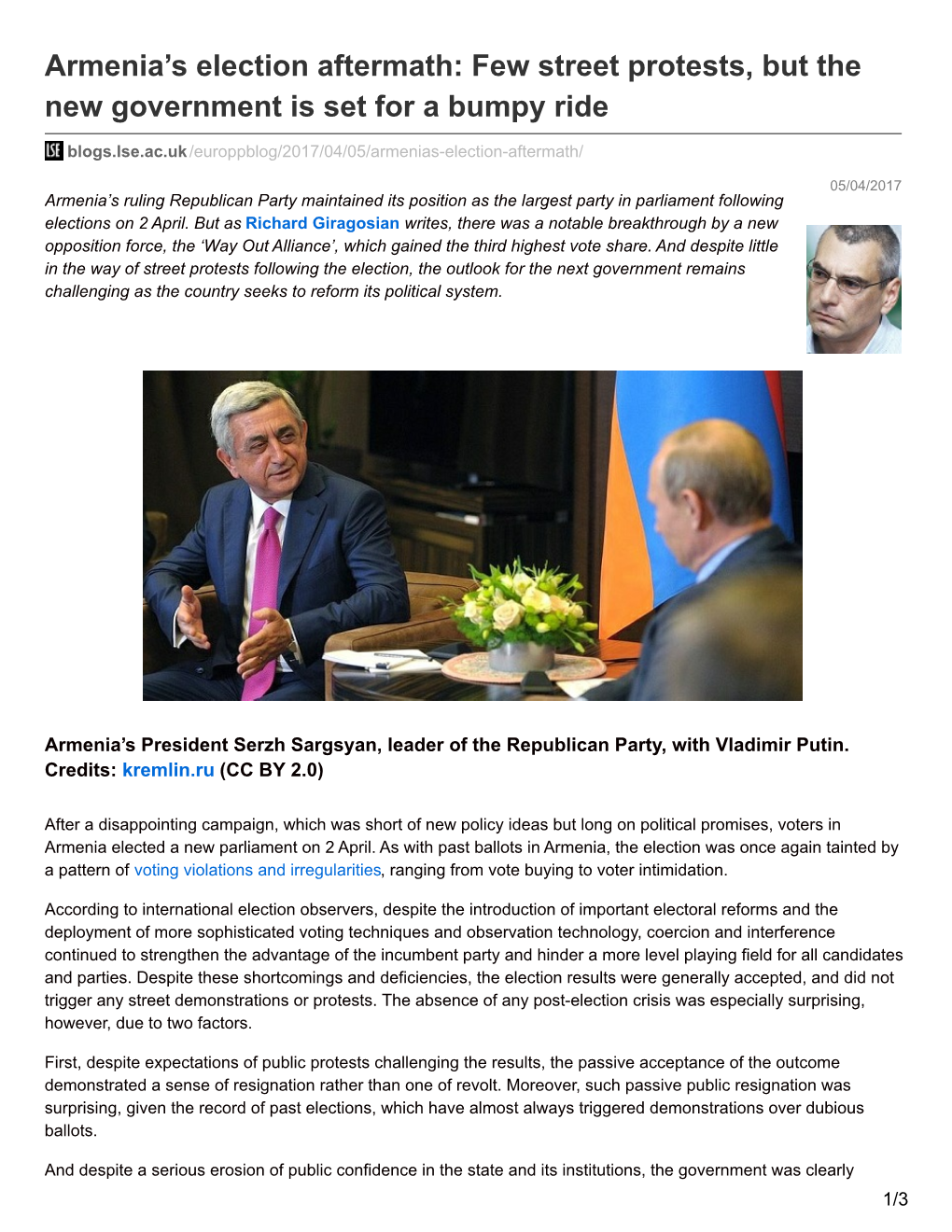

04.03.2017-10.04.2017 • No: 110 EVALUATION OF THE APRIL 2, 2017 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA The 6th parliamentary elections were held in context, the period of socio-economic tension in Under these conditions, 1,500 deputy candidates Armenia on April 2, 2017. According to the the country, where alliance ties with Russia participated in the recent elections. According to unofficial results announced by the Armenian (especially military field) have been strength- the results of 2009 polling stations operated in 13 Central Election Commission, 60.86% (namely ened. As known, it is expected that the Constitu- electoral districts nationwide, the distribution of 1,575,382) of the 2,588,590 registered voters tional reform, with its first four chapters entered votes is as follows: the Republican Party of participated in the elections and the Republican into force on December 22, 2015, will be com- Armenia 49.17% (771,247); the Tsarukyan Alli- Party of Armenia won with 49.17% (771,247) of pleted by April 2018. The Constitutional Reform, ance 27.35% (428,965); the Way Out Alliance total votes. which was launched by the initiative of the Pres- 7.78% (122,049); the Armenian Revolutionary According to the Article 89 of the Constitution of ident Serzh Sargsyan, was supported by the Federation “Dashnaksutyun” Party 6.58% the Republic of Armenia with the amendments, Armenian Republican Party, the Prosperous (103,173); the Armenian Renaissance Party which were introduced by the referendum on Armenia Party and the Armenian Revolutionary 3.72% (58,277); the Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanian December 6, 2015, Armenia has a single legisla- Federation “Dashnaksutyun” Party. -

Ditord 2016-01Englnew.Qxd

January 2016 ITORDOBSERVER (70) HUMAND RIGHTS IN #ARMENIA1 Helsinki Committee of Armenia HUMAN RIGHTS IN ARMENIA The Project is implementedo with the support from DiiOpent Society Foundationsrd ITORD D OBSERVER #1 2016 Project Director and Person in Charge of the Issue Mr. Avetik Ishkhanian Graphic Designer Mr. Aram Urutian Helsinki Translator Mr. Vladimir Osipov Committee Photoes by Photolure of Armenia News Agency Helsinki Committee Of Armenia Non-govermmental Human Rights Organization State Registration Certificate N 1792 Issued on 20.02.1996 Re-registration 21.05.2008, then 09.01.2013 Certificate N 03 ² 080669. Print run 300 copies Address: 3a Pushkin Street, 0010 - Yerevan, Republic of Armenia Tel.: (37410) 56 03 72, 56 14 57 E-mail:[email protected] www.armhels.com CONTENTS HUMAN RIGHTS IN ARMENIA IN 2015 Human Rights in Armenia in 2015 . 3 Referendum on Constitutional Amendments . 7 The Right to Freedom of Speech . 9 Freedom of Peaceful Assembly . 11 Torture, Violence and Political Persecution . 14 Freedom of Conscience and Religion . 20 Human Rights in Armenia 2015 REPORT The REPORT has been drawn up by Helsinki Committee of Armenia in cooperation with Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression (The Right to Freedom of Speech Section), Collaboration for Democracy Centre (Freedom of Conscience and Religion Section) and Armenian Innocence Project (Issues of Life-termers subsection) non-governmental organizations Helsinki Committee of Armenia 2016 DITORD/OBSERVER #1. 2016 2 Human Rights in Armenia in 2015 12 January 2015, the public felt tering a police wall the protesters turned rally Ondeep indignation and anger into a sit-in and stayed on Baghramyan because of a murder of 7 members of Avenue. -

Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia

Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia July 23–August 15, 2018 Detailed Methodology • The survey was coordinated by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene from Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the Center for Insights in Survey Research. The field work was carried out by the Armenian Sociological Association. • Data was collected throughout Armenia between July 23 and August 15, 2018, through face-to-face interviews in respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 1,200 permanent residents of Armenia older than the age of 18 and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, region and size/type settlement. • Sampling frame: Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia. Weighting: Data weighted for 11 regional groups, age and gender. • A multistage probability sampling method was used, with the random route and next birthday respondent selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Armenia are grouped into 11 regions. The survey was conducted throughout all regions of Armenia. The city of Yerevan was treated as a separate region. • Stage two: The territory of each region was split into settlements and grouped according to subtype (i.e. cities, towns and villages). • Settlements were selected at random. • The number of settlements selected in each region was proportional to the share of population living in the particular type of settlement in each region. • Stage three: Primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus or minus 2.5 percent for the full sample. • The response rate was 64 percent. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. -

Engage in a Dialogue And, Consequently, a Meeting Between Pashinyan and Sargsyan (Serzh) Was Held on April 22

THE VELVET REVOLUTION – ARMENIAN VERSION IVLIAN HAINDRAVA 113 EXPERT OPINION ÓÀØÀÒÈÅÄËÏÓ ÓÔÒÀÔÄÂÉÉÓÀ ÃÀ ÓÀÄÒÈÀÛÏÒÉÓÏ ÖÒÈÉÄÒÈÏÁÀÈÀ ÊÅËÄÅÉÓ ×ÏÍÃÉ GEORGIAN FOUNDATION FOR STRATEGIC AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES EXPERT OPINION IVLIAN HAINDRAVA THE VELVET REVOLUTION – ARMENIAN VERSION 113 2019 The publication is made possible with the support of the US Embassy in Georgia. The views expressed in the publication are the sole responsibility of the author and do not in any way represent the views of the Embassy. Technical Editor: Artem Melik-Nubarov All rights reserved and belong to Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, including electronic and mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The opinions and conclusions expressed are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies. Copyright © 2019 Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies ISSN 1512-4835 ISBN 978-9941-8-0960-6 Early parliamentary elections in Armenia on December 9 put a legal end to a nine- month process of the change of power. The Velvet Revolution, as it was labeled by the principal creator of this revolution, Nikol Pashinyan, is over. The complex stage of fulfilling the revolutionary promises begins which will reveal whether or not it was worth a try. Let me start telling about the 2018 adventure of our neighbor and friend – Armenia – with a “confession testimony.” Almost a year ago at a discussion held at the Levan Mikeladze Foundation, I argued that, despite the new constitutional model to come into force (more about this later), Armenia was not going to face any major shock waves. -

The Velvet Revolution in Armenia: How to Lose Power in Two Weeks Alexander Iskandaryan

The Velvet Revolution in Armenia: How to Lose Power in Two Weeks Alexander Iskandaryan Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, Volume 26, Number 4, Fall 2018, pp. 465-482 (Article) Published by Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, The George Washington University For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/707882 No institutional affiliation (20 Jan 2019 19:09 GMT) Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 26: 4 (Fall 2018): pp. 465-482. THE VELVET REVOLUTION IN ARMENIA: HOW TO LOSE POWER IN TWO WEEKS ALEXANDER ISKANDARYAN CAUCASUS INSTITUTE, YEREVAN Abstract: The 2018 power transition in Armenia, known as the Velvet Revolution, took place roughly a year after the 2017 parliamentary election, in which the only opposition bloc of three parties—including the Civil Contract Party, led by Nikol Pashinyan, the future revolutionary leader— won just over 7% of the vote. The newly elected opposition MPs did not dispute the results of the election, but just a year later, mass protests toppled the regime in two weeks and Pashinyan became the new head of state. This article argues that the 2017 success and the 2018 demise of Armenia’s regime had the same cause: the absence of a developed political party system in Armenia. It also argues that the revolution was triggered by a lack of alternative modes of mass political engagement and made possible by the weakness of the regime—its “multiple sovereignty.” As a result, new elites were formed ad hoc from the pool of people who rose to power as a result of civil strife and who often adhere to a Manichaean worldview. -

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Armenia Early Parliamentary Elections, 9 December 2018

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Armenia Early Parliamentary Elections, 9 December 2018 INTERIM REPORT 12-25 November 2018 28 November 2018 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On 1 November, the President announced early parliamentary elections to be held on 9 December. These elections are a result of a tactical resignation by the Prime Minister on 16 October, aimed at dissolving the parliament, following a political agreement to hold early elections. The legal framework for parliamentary elections was last amended in May 2018. Amendments to the electoral code and pertinent legislation enhanced measures to prevent abuse of state resources, lifted restrictions on representatives of the media and set greater sanctions and penalties for electoral offenses. On 17 October, the government submitted draft amendments aimed at changing the electoral system to a purely proportional one and other significant adjustments but ultimately did not receive a required three-fifths’ majority in the parliament. A minimum of 101 MPs are elected through a two-tier proportional system, with candidates elected from a closed, ordered national list and 13 open district lists. In case no majority can be formed within six days of official results, a second round is held between the top two candidate lists 28 days after election day. Four seats are reserved for candidates coming from the largest national minorities. Elections are administered by the Central Election Commission (CEC), 38 Territorial Election Commissions (TECs) and 2,010 Precinct Election Commissions (PECs). The CEC is holding regular sessions and reaching decisions collegially and unanimously. No concerns were raised so far about the confidence in the CEC and TECs.