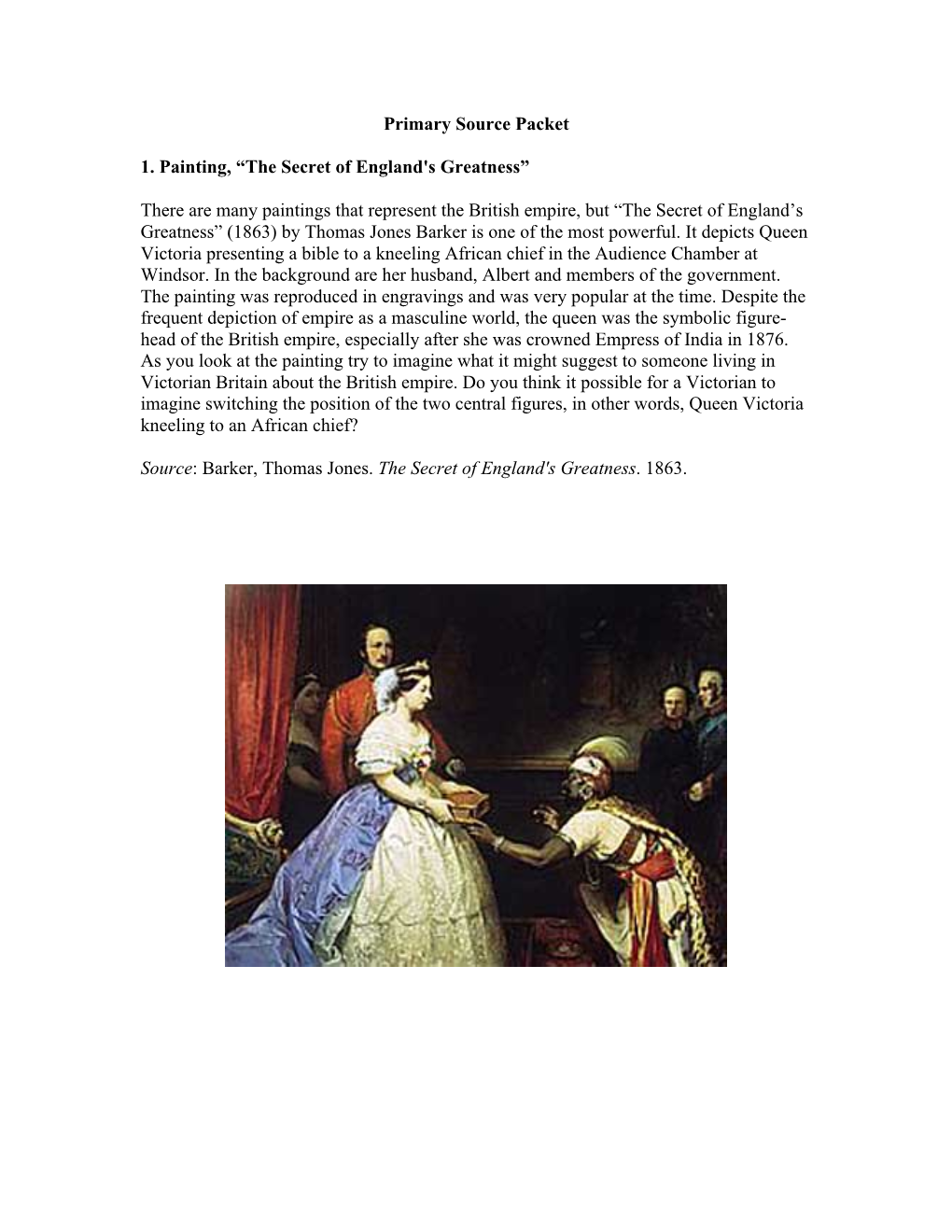

Primary Source Packet 1. Painting, “The Secret of England's Greatness” There Are Many Paintings That Represent the British E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Télécharger Article

ﻣﺠﻠﺔ دراﺳﺎت دﻳﺴﻤﺒﺮ 2015 British Intervention in Afghanistan and its Aftermath (1838-1842) Mehdani Miloud * and Ghomri Tedj * Tahri Mohamed University ( Bechar ) Abstract The balance of power that prompted the European powers to the political domination and economic exploitation of the Third World countries in the nineteenth century was primarily due to the industrialization requirements. In fact, these powers embarked on global expansion to the detriment of fragile states in Africa, South America and Asia, to secure markets to keep their machinery turning. In Central Asia, the competition for supremacy and influence involved Britain and Russia, then two hegemonic powers in the region. Russia’s steady expansion southwards was to cause British mounting concern, for such a systematic enlargement would, in the long term, jeopardize British efforts to protect India, ‘the Crown Jewel.’ In their attempt to cope with such contingent circumstances, the British colonial administration believed that making of Afghanistan a buffer state between India and Russia, would halt Russian expansion. Because this latter policy did not deter the Russians’ southwards extension, Britain sought to forge friendly relations with the Afghan Amir, Dost Mohammad. However, the Russians were to alter these amicable relations, through the frequent visits of their political agents to Kabul. This Russian attitude was to increase British anxiety to such a degree that it developed to some sort of paranoia, which ultimately led to British repeated armed interventions in Afghanistan. Key Words: British, intervention, Afghanistan, Great Game Introduction The British loss of the thirteen colonies and the American independence in 1883 moved Britain to concentrate her efforts on India in which the East India Company had established its foothold from the beginning of the seventeenth century up to the Indian Mutiny (1857). -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

Carol Orchard October 2016

A Victorian Paradox: Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler Background notes Carol Orchard - 19 October 2016 Calling the Roll after an Engagement, Crimea (1874) HM The Queen Winchester Art History Group www.wahg.org.uk 1 “Thank God I never painted for the glory of war, but to portray its pathos and heroism.” The popularity of the arts - including the visual arts - increased enormously in England during the 19th century. As the middle classes expanded and became more prosperous, their appetite for art grew. Galleries opened, attracting queues of enthusiasts, and prints of popular paintings sold in their thousands. Art schools sprang up and, for the first time (in Britain, at least), began opening their doors to women, thus removing one of the main barriers to the profession for them. It was still unusual, but no longer unthinkable, for women to train as artists. Elizabeth Thompson, born to English parents in Lausanne, brought up largely in Italy, and educated at home by her father, was an early beneficiary of this liberalisation. She chose a genre - battle painting - which was highly esteemed in France but largely unexploited in England, and her success was almost immediate. An early commission - ‘Calling the Roll after an Engagement, Crimea’ - became such a sensation at the Royal Academy show in 1874 that policemen were needed to control the crowds. It then went on a national tour and was the subject of a bidding war between the Queen and the businessman who had originally bought it. Thompson herself said that she never intended to glorify war, but her battle paintings clearly caught aspects of the public mood (eg. -

Mary Lago Collection Scope and Content Note

Special Collections 401 Ellis Library Columbia, MO 65201 (573) 882-0076 & Rare Books [email protected] University of Missouri Libraries http://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/ Mary Lago Collection Scope and Content Note The massive correspondence of E. M. Forster, which Professor Lago gathered from archives all over the world, is one of the prominent features of the collection, with over 15,000 letters. It was assembled in preparation for an edition of selected letters that she edited in collaboration with P. N. Furbank, Forster’s authorized biographer. A similar archive of Forster letters has been deposited in King’s College. The collection also includes copies of the correspondence of William Rothenstein, Edward John Thompson, Max Beerbohm, Rabindranath Tagore, Edward Burne-Jones, D.S. MacColl, Christiana Herringham, and Arthur Henry Fox-Strangways. These materials were also gathered by her in preparation for subsequent books. In addition, the collection contains Lago’s extensive personal and professional correspondence, including correspondence with Buddhadeva Bose, Penelope Fitzgerald, P.N. Furbank, Dilys Hamlett, Krishna Kripalani, Celia Rooke, Stella Rhys, Satyajit Ray, Amitendranath Tagore, E.P. Thompson, Lance Thirkell, Pratima Tagore, John Rothenstein and his family, Eric and Nancy Crozier, Michael Holroyd, Margaret Drabble, Santha Rama Rau, Hsiao Ch’ien, Ted Uppmann, Edith Weiss-Mann, Arthur Mendel, Zia Moyheddin and numerous others. The collection is supplemented by extensive files related to each of her books, proof copies of these books, and files related to her academic career, honors, awards, and memorabilia. Personal material includes her journals and diaries that depict the tenuous position of a woman in the male-dominated profession of the early seventies. -

Through Most of Art History Women Artists Have Been Largely Ignored

SESSION 18 Women artists 1400 - 2000 (Monday 3rd February & Tuesday 7th January) 1. Sofonisba Anguissola 1.1. The Chess Game 1555 Oil on canvas, National Museum Warsaw (72 X 97 cm) 2. Barbara Longhi, 2.1. Madonna and Child 1580-85 Oil on canvas, Indianopolis Museum of Art (48 X29 cm) 3. Lavinia Fontana, 3.1. Minerva Dressing 1613 Borghese Gallery, Rome 4. Artemisia Gentileschi, 4.1. Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting 1638 Oil on canvas, Royal Collection, London (96 X 74 cm) 5. Rachel Ruysch, 5.1. Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies, and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge 1688 Oil on canvas, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington 6. Judith Leyster, 6.1. The Proposition 1631 Oil on panel, Mauritshuis, The Hague (31 X 24 cm) 7. Angelica Kauffman 7.1. The Sorrow of Telemachus 1783 Oil on canvas, MMA New York (33 X 114 cm) [ and see The Conjurer 1775 by Nathaniel Hone] 8. Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun 8.1. Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie 1789 Oil on canvas , Louvre, Paris (130 X 94cm) 9. Marie-Denise Villers, 9.1. Portrait of Charlotte du Val d'Ognes, 1801, oil on canvas MMA, New York 10. Emily Mary Osborn 10.1. Nameless and Friendless 1857 Tate Britain Oil on canvas (82 X 103 cm) 11. Rebecca Solomon 11.1. The Governess 1851 Oil on canvas, (66 X 86 cm) 12. Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) 12.1. Scotland Forever 1881 Oil on canvas, Leeds Art Gallery 13. Rosa Bonheur 13.1. Ploughing in the Nivernais 1849 Oil on canvas, Musee D’Orsay (133 X 260 cm) 14. -

The First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42 44

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier Thesis How to cite: Malhotra, Shane Gail (2013). Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000d5b1 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Title Page Name: Shane Gail Malhotra Affiliation: English Department, Faculty of Arts, The Open University Dissertation: 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' Degree: PhD, English Disclaimer 1: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier', is all my own work and no part of it has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification to this or any other university or institution, nor has any material previously been published. Disclaimer 2: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' is within the word limit for PhD theses as stipulated by the Research School and Arts Faculty, The Open University. -

British Interventions in Afghanistan and the Afghans' Struggle To

University of Oran 2 Faculty of Foreign Languages Doctoral Thesis Submitted in British Civilization Entitled: British Interventions in Afghanistan and the Afghans’ Struggle to Achieve Independence (1838-1921) Presented and submitted Publicaly by by: Mr Mehdani Miloud in front of a jury composed of Jury Members Designation University Pr.Bouhadiba Zoulikha President Oran 2 Pr. Lahouel Badra Supervisor Oran 2 Pr. Moulfi Leila Examiner Oran 2 Pr. Benmoussat Smail Examiner Tlemcen Dr. Dani Fatiha Examiner Oran 1 Dr. Meberbech Fewzia Examiner Tlemcen 2015-2016 Dedication To my daughter Nardjes (Nadjet) . Abstract The British loss of the thirteen colonies upon the American independence in 1783 moved Britain to concentrate her efforts on India. Lying between the British and Russian empires as part of the Great Game, Afghanistan grew important for the Russians, for it constituted a gateway to India. As a result, the British wanted to make of Afghanistan a buffer state to ward off a potential Russian invasion of India. Because British-ruled India government accused the Afghan Amir of duplicity, she intervened in Afghanistan in 1838 to topple the Afghan Amir, Dost Mohammad and re-enthrone an Afghan ‗puppet‘ king named Shah Shuja. The British made their second intervention in Afghanistan (1878-1880) because the Anglo-Russian rivalry persisted. The result was both the annexation of some of the Afghans‘ territory and the confiscation of their sovereignty over their foreign policy. Unlike the British first and second interventions in Afghanistan, the third one, even though short, was significant because it was instigated by the Afghan resistance. Imbued with nationalist and Pan-Islamist ideologies, the Afghans were able to free their country from the British domination. -

Representations of Afghan Women by Nineteenth Century British Travel Writers

REPRESENTATIONS OF AFGHAN WOMEN BY NINETEENTH CENTURY BRITISH TRAVEL WRITERS A Master’s Thesis by MARIA NAWANDISH Department of History Ġhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2015 To my parents REPRESENTATIONS OF AFGHAN WOMEN BY NINETEENTH CENTURY BRITISH TRAVEL WRITERS Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MARIA NAWANDISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ĠHSAN DOĞRAMACI BĠLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2015 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------- Assist. Prof. David Thornton Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------- Assist. Prof. Paul Latimer Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------- Assoc. Prof. Cemile Akça Ataç Examining Committee Member Approval of the Graduate school of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT REPRESENTATIONS OF AFGHAN WOMEN BY NINETEENTH CENTURY BRITISH TRAVEL WRITERS Nawandish, Maria M.A., Department of History Supervisor: Assist. Prof. David Thornton September 2015 This thesis attempts to represent the life of Afghan women in the nineteenth century (during the Anglo-Afghan wars) through a qualitative and quantitative study of accounts by English travel writers using an Orientalist and travel writing discourse. -

Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority

ETHNOHISTORY OF THE QIZILBASH IN KABUL: MIGRATION, STATE, AND A SHI’A MINORITY Solaiman M. Fazel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology Indiana University May 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, PhD __________________________________________ Anya Peterson Royce, PhD __________________________________________ Daniel Suslak, PhD __________________________________________ Devin DeWeese, PhD __________________________________________ Ron Sela, PhD Date of Defense ii For my love Megan for the light of my eyes Tamanah and Sohrab and for my esteemed professors who inspired me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This historical ethnography of Qizilbash communities in Kabul is the result of a painstaking process of multi-sited archival research, in-person interviews, and collection of empirical data from archival sources, memoirs, and memories of the people who once live/lived and experienced the affects of state-formation in Afghanistan. The origin of my study extends beyond the moment I had to pick a research topic for completion of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University. This study grapples with some questions that have occupied my mind since a young age when my parents decided to migrate from Kabul to Los Angeles because of the Soviet-Afghan War of 1980s. I undertook sections of this topic while finishing my Senior Project at UC Santa Barbara and my Master’s thesis at California State University, Fullerton. I can only hope that the questions and analysis offered here reflects my intellectual progress. -

View for the British

Lord Ellenborough: The Pro-military Governor General of India Lord Ellenborough (Edward Law, 1st Earl of Ellenborough) was the Governor General of India from 28 February 1842 to June 1844. He was born on 8 September 1790 in London. His father's name was Edward Law, 1st Baron of Ellenborough. His father was the Member of Parliament. He represented the Newtown Parliamentary Borough on the Isle of Wight. He was appointed as the Attorney General by Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, who was the Prime Minister of UK from 17 March 1801 to 10 May 1804. He also acted as the Her Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales. The person holding this position is mostly called as the Attorney General and is the Law Officer to the British Crown and British Government. Attorney General can attend the meetings of Cabinet. Apart from giving legal advice to the British Crown and the Government, Attorney General represents them in the Court of Law. In 1802, Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough, became the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. This Legal Officer is considered as the Head of the Judiciary of England and Wales and also President of the Courts of England and Wales. He was also made the Baron of Ellenborough, a suburb in Maryport, Cumbria (Northwestern England). He was the Member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom. The Privy Council is the Advisory Body to the Crown of United Kingdom. The mebership of Privy Council is given to the senior politicians who are either the current or former members of House of Commons or House of Lords. -

The Revd. John Stuart, DD, UEL of Kingston, UC

FROM-THE- LIBRARYOF TR1NITYCOLLEGETORDNTO FROM-THE- LIBRARY-OF TWNITYCOLLEGETORQNTO & FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE LATE COLONEL HENRY T. BROCK DONATED NOVEMBER. 1933 The Revd. John Stuart D.D., U.E.L. OF KINGSTON, U. C. and His Family A Genealogical Study by A. H. YOUNG 19 Contents PACK Portraits of Dr. John Stuart and his wife, Jane Okill viii Preface 1 Note on the Origin and Distribution of the Stuart Family in Canada 7 The Revd. John Stuart and Jane Okill 9 I. George-Okill Stuart and his Wives 10 II. John Stuart, Jr., and Sophia Jones 12 III. Sir James Stuart, Bart., and Elizabeth Robertson 27 IV. Jane Stuart 29 V. Charles Stuart and Mary Ross 29 VI. The Hon. Andrew Stuart and Marguerite Dumoulin 30 VII. Mary Stuart and the Hon. Charles Jones, M.L.C 41 VIII. Ann Stuart and Patrick Smyth 44 Extract from Dr. Strachan's Funeral Sermon on Dr. John Stuart 47 The Only Sermon of Dr. John Stuart known to be extant 55 Addenda . 62 Preface little study of the distinguished Stuart family, founded by the Revd. John Stuart, D.D., of Kings THISton, has grown out of researches for a Life of Bishop Strachan, who called him "my spiritual father." Perusal of original letters to the Society for the Propa gation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, together with the Society's Journals and Annual Reports from 1770 to 1812-, gives one a good idea of "the little gentleman," as he was called, notwithstanding his six feet four inches, even before he left the Province of New York in 1781. -

Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan Company to Explore the Ancient Sites in South-East Afghanistan

From 1833–8, Charles Masson (1800–1853) was employed by the British East India Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan Company to explore the ancient sites in south-east Afghanistan. During this period, he surveyed over a hundred Buddhist sites around Kabul, Jalalabad and Wardak, making numerous drawings of the sites, together with maps, compass readings, sections of the stupas and sketches of some of the finds. Small illustrations of a selection of these key sites were published in Ariana Antiqua in 1841. However, this represents only a tiny proportion of his official and private correspondence held in the India Office Collection of the British Library which is studied in detail in this publication. It is supplemented online by The Charles Masson Archive: British Library and British Museum Documents Relating to the 1832–1838 Masson Collection from Afghanistan (British Museum Research Publication number 216). Together they provide the means for a comprehensive reconstitution of the archaeological record of the sites. In return for funding his exploration of the ancient sites of Afghanistan, the British East India Company received all of Masson’s finds. These were sent to the India Museum in London, and when it closed in 1878 the British Museum was the principal recipient of all the ‘archaeological’ artefacts and a proportion of the coins. This volume studies the British Museum’s collection of the Buddhist relic deposits, including reliquaries, beads and coins, and places them within a wider historical and archaeological context for the first time. Masson’s collection of coins and finds from Begram are the subject of a separate study.