Long Road 2006-01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Average 27Mph! the Yeovil Cycling Club July 2007

THE Yeovil Cycling Club July 2007 Average 27mph! The John Andrews Memorial Road One rider was not so lucky, he signed Race was open to 2nd, 3rd and 4th on and collected his number but when category riders and attracted an entry of he returned to his car he found he had over 70 from all over the South and West, locked his bike inside along with the keys from Surrey to Cornwall. Unfortunately and the breakdown could not reach him there were no entries from the promoting in time for the start! club! The race was run at a very fast pace with attacks on every lap, Stuart Dodd Results (Team Tor 2000) was one who enjoyed 1 Andrew Hitchens Mid Devon CC a few miles off the front in the first few 2 Grant Leavy Club 18 To Dirty miles. As the pace, over 25mph, began to 3 Philip Borrett Bikinmotion Cycling Club tell an attack from the ever active Cornish 4 Serge Scott John's Bikes RT Team Certini on the drag up through 5 Jason Flooks Team Certini Upton split the field and enabled the 6 Rex Facey 1st Chard Whls winning break of 7 to gain a gap of a 7 Julius Renn-Jennings Gillingham and District Whls minute. At the hard uphill finish Andrew 8 Dean Robson Ajchva Limoux Hitchens pulled clear to win by 3 seconds 9 Ian Rees Climb On Bikes RT from Grant Leavey. The best local riders 10 James Smith Team Certini were Rex Facey (1st Chard Wheelers) and 11 Andrew Rivett Sotonia CC Julius Jennings (Gillingham & District Whs) 12 Edward Griffin Bournemouth Arrow CC Winner Hitchens now a veteran of 41 13 Barry Clewett Bournemouth Arrow CC won this race in 1990 when it was open 14 Matthew Ewings Exeter Wheelers to 1st category riders and over 80 miles. -

Le Journaliste Sportif Est-Il Un Journaliste Comme Les Autres ?

2018 Mémoire de fin d’études Mastère « Journalisme de sport » Le journaliste sportif est-il un journaliste comme les autres ? PRESENTE PAR SYLVAIN FALCOZ DIRECTEUR DE MEMOIRE : YASMINA TOUAIBIA Promotion Pierre Barbancey 1 Résumé L’étude qui va être menée dans les pages suivantes vise à questionner la place et la reconnaissance du journaliste sportif vis-à-vis de ses confrères des autres rubriques. L’analyse de la manière dont il travaille, le rapport qu’il entretient avec ses sources, permettront notamment de comprendre quelles sont ses spécificités, et de déterminer s’il est réellement un journaliste comme les autres. Chaque été, principalement les années où se déroulent des événements sportifs planétaires (Jeux Olympiques, Coupe du Monde de football…) le journaliste sportif est mis sur le devant de la scène. Et ce d’autant plus que la période estivale n’est pas toujours la plus faste en matière d’actualité journalistique. Mais bien souvent, la mise en lumière de ces conteurs du sport ne leur est pas forcément bénéfique. Raillé pour son chauvinisme exacerbé, sa proximité avec les athlètes ou ses envolées lyriques, le journaliste sportif n’a pas toujours bonne presse. Etroitement lié à son objet d’étude, à ses traditions, et à ce qu’on aurait coutume d’appeler « la grande famille du sport », ce dernier s’est construit à travers des singularités qui permettent de se demander s’il exerce en tous points le même métier que ces nombreux confrères. Summary The following study aims at questionning on the place and recognition of the sports journalist with respect to his colleagues working in the other sections. -

TOUR DE FRANCE 6 Juillet Samedi 5 Juillet SHEFFIELD

YORKSHIRE Grand Départ HARROGATEATE YORK dimanche LEEDS TOUR DE FRANCE 6 juillet samedi 5 juillet SHEFFIELD GRANDE-BRETAGNE CAMBRIDGE lundi 7 juillet LONDRES mercredi YPRES 9 juillet BELGIQUE LE TOUQUET LILLE PARIS-PLAGE ARRAS mardi 8 juillet ARENBERG PORTE DU HAINAUT jeudi 10 juillet vendredi REIMS 11 juillet PARIS Champs-Élysées ÉPERNAY TOMBLAINE dimanche 27 juillet ÉVRY NANCY samedi GÉRARDMER 12 juillet lundi 14 juillet LA PLANCHE DES BELLES FILLES MULHOUSE dimanche 13 juillet BESANÇON Repos mardi 15 juillet mercredimercredi 16 juillet BOURG-EN-BRESSE OYONOYONNAXNAX jeudi 17 juillet vendredi 18 juillet SAINT-ÉTIENNE CHAMROUSSECHAMROUSSE PÉRIGUEUX samedi 26 juillet samedi GRENOBLE 19 juillet BERGERAC RISOUL TALLARD vendredi 25 juillet dimanche 20 juillet MAUBOURGUET NÎMES PAU VAL D’ADOUR HAUTACAM SAINT-GAUDENS jeudi 24 CARCASSONNE juillet Repos mardi 22 juillet lundi 21 juillet SAINT-LARY BAGNÈRES-DE-LUCHON PLA D’ADET mercredi 23 juillet ESPAGNE ©A.S.O. 2013 - TDF14_Carte-40x60_V50.indd 1 26/03/14 11:49 4 Préface e Tour, chacun le sait, est plus qu’une course cycliste. S’il occupe une place de choix dans les gazettes sportives, il La aussi, grâce à son grand âge et avec sa façon de sillonner de long en large la France, et même l’Europe, intégré les manuels d’histoire et de géographie. Pour plus d’un gamin du XXe siècle, la Grande Boucle fut un moyen commode de réviser sa carte de France. Grâce au vélo, les plus grands sommets des Alpes et des Pyrénées sont presque devenus des noms communs. Cette année, ce sont les Vosges que le Tour a voulu mettre à l’honneur et rappeler qu’il fut le premier massif franchi par le peloton dès 1905. -

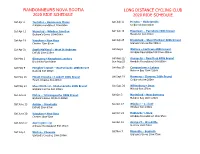

2020 Ride Schedule 2020 Ride Schedule

RANDONNEURS NOVA SCOTIA LONG DISTANCE CYCLING CLUB 2020 RIDE SCHEDULE 2020 RIDE SCHEDULE Sat Apr 4 Tantallon - Hammonds Plains Sat July 11 Morden – Harbourville Armdale roundabout 10AM 60KM Coldbrook 10AM 86KM Sat Apr 11 Waverley – Windsor Junction Sat July 18 Masstown – Parrsboro 200k brevet Graham’s Grove 10AM 58KM Masstown 8AM 200KM Sat Apr 18 Vaughan – New Ross Sat July 25 Brookfield – Sheet Harbour 300k brevet Chester 10AM 92KM Graham’s Grove 6AM 300KM Sat Apr 25 South Maitland – West St Andrews Sat Aug 8 Wallace – Earltown 400k brevet Enfield 10AM 119KM Armdale Roundabout 00:01AM 400KM Sat May 2 Glengarry – Kemptown century Sat Aug 22/ Annapolis – New Ross 600k brevet Brookfield 9AM 168KM Sun Aug 23 Armdale Roundabout 6AM 600KM Sat May 9 Meagher’s Grant – East Uniacke 200k Brevet Sat Aug 29 Camperdown – Lahave Bedford 8AM 200KM Mahone Bay 10AM 120KM Sat May 16 Mount Uniacke – Lookoff 200k Brevet Sat Sept 19 Harmony – Clarence 200k Brevet Mount Uniacke 8AM 200KM Coldbrook 8AM 200KM Sat May 23 Sheet Harbour– Shubenacadie 300k Brevet Sat Sept 26 Wittenburg – Dean Graham’s Grove 6AM 300KM Milford 9AM 135KM Sat June 6 Pictou – Tatamagouche 400k Brevet Sat Oct 3 Northfield – New Germany Graham’s Grove 00:01AM 400KM Mahone Bay 10AM 120KM Sat June 13 Antrim – Stewiacke Sat Oct 17 Windsor – Lookoff Enfield 10AM 87KM Windsor 9AM 130KM Sat June 20 Vaughan – New Ross Sat Oct 24 Hubbards ‘n Back Chester 10AM 92KM Armdale Roundabout 10AM 95KM Sat June 27 Aspotogan loop Sat Oct 31 Avonport – Woodville Armdale Roundabout 9AM 145KM St Croix 10AM 74KM Sat July 4 Walton - Cheverie Sat Nov 7 Mineville – Seaforth Graham’s Grove 10AM 75KM Garland’s Crossing 10AM 100KM Randonneurs Nova Scotia Long Distance Cycling Club What is Randonneuring? In a nutshell, randonneur cycling is long-distance non-competitive cycling. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Michelin, La Leçon De Choses Janvier 2017 4 Tristan De La Broise

Tristan de la Broise MICHELIN La leçon de choses 1832-2012 Michelin, la leçon de choses Janvier 2017 4 Tristan de la Broise De l’invention de la roue à celle du pneu, combien de temps s’est-il écoulé ? Pourquoi une découverte aussi importante a-t-elle autant tardé ? Certains affirment – pas seulement chez Michelin – que sans le pneu, il n’y aurait pas eu de bicyclette ni d’automobile. Ou alors, si peu. Et roulant si mal. C’est une histoire déconcertante. En effet, quoi de plus élémentaire qu’un pneu ? Mais le génie de Michelin est d’en avoir fait, dans sa poursuite de l’excellence, un produit de haute technologie, aussi complexe dans sa conception, dans ses constituants et dans sa réalisation que simple dans son utilisation. À l’inverse d’autres industries, qui banalisent les appareils les plus compliqués, Michelin s’est ingéniée à rendre le pneu toujours plus performant, plus sophistiqué. « Si le pneu ne vous passionne pas, vous n’avez rien à faire dans cette Maison » assure Marius Mignol, génial inventeur du Radial au jeune François Michelin lorsqu’il entre à la Manufacture en 1955. La passion, c’est celle de la recherche, de l’innovation. C’est celle que partagent les dirigeants, les ingénieurs, tout le personnel. Le fruit en est le pneu X dont les nombreuses déclinaisons hissent en un demi-siècle l’entreprise auvergnate au rang des leaders mondiaux. Un demi- siècle supplémentaire de course pour l’immortel Bibendum qui double ainsi sa durée de vie tout en rajeunissant sa silhouette, défiant et séduisant tous les publicitaires de la planète. -

Pinarello Maat Whitepaper

MAAT WHITE PAPER 1.0 PINARELLO MAAT © Cicli Pinarello Srl - All rights reserved - 2019 MAAT WHITE PAPER 2 © Cicli Pinarello Srl - All rights reserved - 2019 MAAT WHITE PAPER CONTENTS 4 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Pinarello 5 1.2 Track Experience Over the Years 6 2. SUMMARY OF THE IMPROVEMENTS 8 3. AERODYNAMICS DESIGN 9 3.1 Headtube 10 3.2 Fork 11 3.3 Seat Stays 11 3.4 Downtube and Seattube 11 3.5 Other Details 12 4. STRUCTURAL DESIGN 12 4.1 Chainstays and Downtube 13 4.2 Material Choice 14 5. CUSTOMIZATION AND VERSATILITY 14 5.1 Multidiscipline 15 5.2 Headset Spacer Versatility 15 5.3 Tire Clearance 16 6. HANDLEBAR 19 7. SIZES 19 7.1 Frame Sizes 19 7.2 Maat Handlebar Sizes 21 8. GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS 21 9. RACING 3 © Cicli Pinarello Srl - All rights reserved - 2019 MAAT WHITE PAPER INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Pinarello Cicli Pinarello S.R.L. is one of the most famous and winning bike manufacturers in the world. Founded in Treviso (Italy) in 1952 by Giovanni (Nani) Pinarello, it produces high end racing bikes. This name, Pinarello, recalls legendary victories of the greatest cyclists of all times: since 1975, the first victory in Giro d’Italia with Fausto Bertoglio, Pinarello has won all the most important races in the world, including Olympics, World Championships and Tour de France. 4 © Cicli Pinarello Srl - All rights reserved - 2019 MAAT WHITE PAPER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.2 Track Experience Over the Years For many years Pinarello has developed track bikes to cover different needs of riders. -

L'épopée Fantastique

L’épopée fantastique 1820-1920, cycles et motos 8 avril - 25 juillet 2016 Musée national de la Voiture du Palais de Compiègne www.musees-palaisdecompiegne.fr Suriray, Vélocipède de course, 1869. ©RMNGP/Tony Querrec La collection de cycles du musée national de la Voiture compte, pour les années 1818-1920, parmi les plus remarquables d’Europe. Une importante acquisition réalisée en 2015 a permis de notablement l’enrichir et se trouve présentée au public à cette occasion. L’exposition L’Epopée fantastique est organisée autour de différentes thématiques comme les innovations techniques, la recherche de vitesse, les loisirs, les courses, les clubs et la pratique cycliste, ainsi que les impacts sociaux liés au développement des deux-roues entre 1820 et 1920. Des emprunts à d’autres musées français comme le musée Auto Moto de Chatellerault et le musée d’Art et d’Industrie de Saint Etienne, ainsi qu’à des collections privées viennent compléter cette première sélection. C’est à l’occasion du 125e anniversaire de la course Paris-Roubaix, dont le départ a lieu à Compiègne depuis presque quarante ans, que l’exposition sera ouverte au public. On pourra y découvrir les origines du cycle et de la moto et l’extraordinaire émulation qui animait les fabricants, les coureurs, les cyclistes et motards de ces années d’expérimentations et d’exploration qui sont synonymes de nouvelles sensations. L’exposition s’articule autour de quatre axes principaux : 1. Les années 1820-1860 : de la draisienne au vélocipède. Né de la draisienne, inventée par le baron allemand Karl Drais, le vélocipède est issu de la mise en place d’un pédalier sur la roue avant, innovation attribuée au français Pierre Michaux en 1861. -

The Illustrator and the Global Wars to Come and the Long History Of

The Illustrator and the Global Wars to Come Albert Robida, La guerre infernale, and the Long History of Imagined Warfare GIULIA IANNUZZI Università di Firenze – Università di Trieste Ne soyez point en peine de ce Heros inconnu qui se presente à vos yeux. Encore qu’il ne soit pas ny de ce Monde ny de ce Siecle, il n’est pas si farouche ny si barbare, qu’il ne soit capable de faire un beau choix, & qu’il n’ait jugé aussi juste de vostre merite, que l’auroient pû faire tous ceux qui ont l’honneur de vous mieux connoistre. JACQUES GUTTIN [MICHEL DE PURE], Épigone, histoire du siècle futur (A Paris: Chez Pierre Lamy, 1659), aij-p.nn. … I must acquiesce, and be content with the Honour and Misfortune, of being the first among Historians (if a mere Publisher of Memoirs may deserve that Name) who leaving the beaten Tracts of writing with Malice or Flattery, the accounts of past Actions and Times, have dar’d to enter by the help of an infallible Guide, into the dark Caverns of Futurity, and discover the Secrets of Ages yet to come. SAMUEL MADDEN, Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (London: Printed for Messieurs Osborn and Longman, Davis, and Batley …, 1733) vol. 1, 3. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit? HERBERT G. -

Characteristics of Track Cycling

Sports Med 2001; 31 (7): 457-468 REVIEW ARTICLE 0112-1642/01/0007-0457/$22.00/0 © Adis International Limited. All rights reserved. Characteristics of Track Cycling Neil P. Craig1 and Kevin I. Norton2 1 Australian Institute of Sport, Track Cycling Unit Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 2 School of Physical Education, Exercise and Sport Studies, University of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia Contents Abstract . 457 1. Track Cycling Events . 458 1.1 Energetics of Track Events . 458 2. Physical and Physiological Characteristics of Track Cyclists . 459 2.1 Body Shape, Size and Composition . 459 2.2 Maximal Oxygen Consumption . 461 2.3 Blood Lactate Transition Thresholds . 461 2.4 Anaerobic Capacity . 461 3. Competition Power Output . 462 3.1 200m Sprint . 462 3.2 1000m Time Trial . 463 3.3 4000m Team Pursuit . 463 3.4 4000m Individual Pursuit . 464 3.5 Madison . 464 4. Programme Design and Monitoring . 465 5. Conclusion . 466 Abstract Track cycling events range from a 200m flying sprint (lasting 10 to 11 seconds) to the 50km points race (lasting ≈1 hour). Unlike road cycling competitions where most racing is undertaken at submaximal power outputs, the shorter track events require the cyclist to tax maximally both the aerobic and anaerobic (oxygen independent) metabolic pathways. Elite track cyclists possess key physical and physiological attributes which are matched to the specific requirements of their events: these cyclists must have the appropriate genetic predisposition which is then maximised through effective training interventions. With advances in tech- nology it is now possible to accurately measure both power supply and demand variables under competitive conditions. -

Iss 701 Aug 2017

Aug 2017 Issue no. 701 Inside this Edition Page Contents 3 Editor's Corner 4 Letters to Ed 7 Road Race Win 8 Graham Webb 1944 - 2017 11 West Midlands Youth Circuit Race 14 Success For Stuart 16 Women Get Separate Cross League Race 18 Tommy Godwin Memorial LVRC Race 21 Coast to Coast France 2017 29 Dates for Your Diary 30 Tommy Godwin Challenge 2017 32 Club Runs - Dave Stephenson 35 Club Contacts Front Cover: Graham Webb Rear Cover: Under 16s looking like they are on a Club Run during the Circuit Race © Christian Bodremon 2 Editor’s Corner Another edition sadly reporting on the death of an old SCC member, Graham Webb and as I’ve found out quite a legend! Summer holidays are upon us, circuit leagues are finishing and CX season is fast approaching, Ed here has decided to register for this year’s West Midlands Cycle Cross League so no doubt tales of woe will follow in future editions. We’ve been busy at the track this year with coaching sessions well attended. Diary constraints have meant I could only attend one of Paul Mann’s Wednesday nights but that was enough for me to be convinced to see a doctor! Well would you believe it, not only had I got a chest infection requiring two rounds of antibiotics, I’ve also been diagnosed with asthma but what a difference that little inhaler makes...thanks for the push guys! A special thanks must go to Mick Edensor who along with his band of volunteers organised the highly successful final round of the West Midlands Youth Circuit League, as Guy Elliot stated “It was impeccably organised. -

1990) Through 25Th (2014

CUMULATIVE INDEX TO THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CYCLE HISTORY CONFERENCES 1st (1990) through 25th (2014) Prepared by Gary W. Sanderson (Edition of February 2015) KEY TO INDEXES A. Indexed by Authors -- pp. 1-14 B. General Index of Subjects in Papers - pp. 1-20 Copies of all volumes of the proceedings of the International Cycling History Conference can be found in the United States Library of Congress, Washington, DC (U.S.A.), and in the British National Library in London (England). Access to these documents can be accomplished by following the directions outlined as follows: For the U.S. Library of Congress: Scholars will find all volumes of the International Cycling History Conference Proceedings in the collection of the United States Library of Congress in Washington, DC. To view Library materials, you must have a reader registration card, which is free but requires an in-person visit. Once registered, you can read an ICHC volume by searching the online catalog for the appropriate call number and then submitting a call slip at a reading room in the Library's Jefferson Building or Adams Building. For detailed instructions, visit www.loc.gov. For the British Library: The British Library holds copies of all of the Proceedings from Volume 1 through Volume 25. To consult these you will need to register with The British Library for a Reader Pass. You will usually need to be over 18 years of age. You can't browse in the British Library’s Reading Rooms to see what you want; readers search the online catalogue then order their items from storage and wait to collect them.