SYNC EVENT the Ethnographic Allegory of Unsere Afrikareise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

Series 29:6) Luis Buñuel, VIRIDIANA (1961, 90 Min)

September 30, 2014 (Series 29:6) Luis Buñuel, VIRIDIANA (1961, 90 min) Directed by Luis Buñuel Written by Julio Alejandro, Luis Buñuel, and Benito Pérez Galdós (novel “Halma”) Cinematography by José F. Aguayo Produced by Gustavo Alatriste Music by Gustavo Pittaluga Film Editing by Pedro del Rey Set Decoration by Francisco Canet Silvia Pinal ... Viridiana Francisco Rabal ... Jorge Fernando Rey ... Don Jaime José Calvo ... Don Amalio Margarita Lozano ... Ramona José Manuel Martín ... El Cojo Victoria Zinny ... Lucia Luis Heredia ... Manuel 'El Poca' Joaquín Roa ... Señor Zequiel Lola Gaos ... Enedina María Isbert ... Beggar Teresa Rabal ... Rita Julio Alejandro (writer) (b. 1906 in Huesca, Arágon, Spain—d. 1995 (age 89) in Javea, Valencia, Spain) wrote 84 films and television shows, among them 1984 “Tú eres mi destino” (TV Luis Buñuel (director) Series), 1976 Man on the Bridge, 1974 Bárbara, 1971 Yesenia, (b. Luis Buñuel Portolés, February 22, 1900 in Calanda, Aragon, 1971 El ídolo, 1970 Tristana, 1969 Memories of the Future, Spain—d. July 29, 1983 (age 83) in Mexico City, Distrito 1965 Simon of the Desert, 1962 A Mother's Sin, 1961 Viridiana, Federal, Mexico) directed 34 films, which are 1977 That 1959 Nazarin, 1955 After the Storm, and 1951 Mujeres sin Obscure Object of Desire, 1974 The Phantom of Liberty, 1972 mañana. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1970 Tristana, 1969 The Milky Way, 1967 Belle de Jour, 1965 Simon of the Desert, 1964 José F. Aguayo (cinematographer) (b. José Fernández Aguayo, Diary of a Chambermaid, 1962 The Exterminating -

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 66,1946-1947

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 SIXTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1946-1947 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ltlC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot .* President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe Nicholas John Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager [577] © © © HOW YOU CAN HAVE A © © Financial "Watch-Dog" © © B © © © B B Webster defines a watch- dog as one kept to watch © and guard." With a Securities Custody Account at © the Shawmut Bank, you in effect put a financial watch- © dog on guard over your investments. And you are re- © lieved of all the bothersome details connected with © © owning stocks or bonds. An Investment Management © Account provides all the services of a Securities Cus- © tody Account and, in addition, you obtain the benefit B the judgment of B of composite investment our Trust B Committee. © Why not get all the facts now, without obligation? © © Call, write or telephone for our booklet: How to be © More Efficient in Handling Your Investments." © © •JeKdimiM \Jwu6t Q/sefi€VKtment © © © The D^ational © © Bank © Shawmut © 40 Water Street^ Boston © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © Capital $ 10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © © "Outstanding Strength" for no Tears © © © I 578 ] 5? SYMPHONIANA LAURELS IN THE WEST At the beginning of this month the Boston Symphony Orchestra gave ten concerts in cities west of New England. -

Michele Greet - Inventing Wilfredo Lam: the Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation

Michele Greet - Inventing Wilfredo Lam: The Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation Back to Issue 5 Inventing Wifredo Lam: The Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation Michele Greet © 2003 "It is — or it should be — a well-known fact that a man hardly owes anything but his physical constitution to the race or races from which he has sprung." 1 This statement made by art critic Michel Leiris could not have been further from the truth when describing the social realities that Wifredo Lam experienced in France in the late 1930s. From the moment he arrived in Paris on May 1, 1938, with a letter of introduction to Pablo Picasso given to him by Manuel Hugué, prominent members of the Parisian avant-garde developed a fascination with Lam, not only with his work, but more specifically with how they perceived race to have shaped his art. 2 Two people in particular took an avid interest in Lam—Picasso and André Breton—each mythologizing him order to validate their own perceptions of non- western cultures. This study will examine interpretations of Lam and his work by Picasso, Breton and other members of the avant-garde, as well as Lam's response to the identity imposed upon him. ******* In 1931, the Colonial Exposition set the mood for a decade in which France asserted its hegemony – in the face of Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and Fascist Italy – through a conspicuous display of control over its colonial holdings. The exposition portrayed the colonies as a pre-industrial lost arcadia, occupied by noble savages who were untouched by the industrial advances of the western world. -

Roger Savage Some Mainland Chinese Work

did you get that soundtrack?’ and the answer was, ‘in Australia’. is because often the actors they use can’t speak very good Soon after that we started doing a lot of low-budget films and Mandarin – their native tongue is often Cantonese, Korean or Roger Savage some Mainland Chinese work. One of these low-budget films even Japanese. In House of Flying Daggers, for instance, some of was directed by Zhang Yimo, who directed Hero in 2004. It the main actors were Korean and Japanese whose Mandarin was So many international awards… so little cupboard space. was through this previous association that we found ourselves unacceptable to the Mainland Chinese audience. To satisfy the working on that film as well. Hero was quite an unusual Chinese audiences the production hired voice artists to come in Andy Stewart talks to Australia’s most decorated film soundtrack, not your typical Hollywood soundtrack. and redo the voice at our studio in Beijing. The Chinese editors mixer about operating Soundfirm and what’s involved in AS: In what way was the Hero soundtrack different? then expertly cut the voice back into the film – they did an RS: The Chinese directors don’t bow down to the studio system, amazing job. Neither House of Flying Daggers nor Hero sound or delivering great sound to a cinema audience. they don’t have to, so they make their films the way they want. look like a dubbed film at all. Often the films themselves are way out there, which often means AS: What’s involved in good ADR in your experience and how the soundtrack is as well. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM

Sync Sound and Indian Cinema | Upperstall.Com 29/02/12 2:30 PM Open Feedback Dialog About : Wallpapers Newsletter Sign Up 8226 films, 13750 profiles, and counting FOLLOW US ON RECENT Sync Sound and Indian Cinema Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya The lead pair of the film, in their real life, went in the The recent success of the film Lagaan has brought the question of Sync Sound to the fore. Sync Sound or Synchronous opposite direction as Sound, as the name suggests, is a highly precise and skilled recording technique in which the artist's original dialogues compared to the pair of the are used and eliminates the tedious process of 'dubbing' over these dialogues at the Post-Production Stage. The very first film this f... Indian talkie Alam Ara (1931) saw the very first use of Sync Feature Jodi Breakers Sound film in India. Since then Indian films were regularly shot I'd be willing to bet Sajid Khan's modest personality and in Sync Sound till the 60's with the silent Mitchell Camera, until cinematic sense on the fact the arrival of the Arri 2C, a noisy but more practical camera that the makers of this 'new particularly for outdoor shoots. The 1960s were the age of age B... Colour, Kashmir, Bouffants, Shammi Kapoor and Sadhana Ekk Deewana Tha and most films were shot outdoors against the scenic beauty As I write this, I learn that there are TWO versions of this of Kashmir and other Hill Stations. It made sense to shoot with film releasing on Friday. -

Du Cinéma and the Changing Question of Cinephilia and the Avant-Garde (1928-1930)

Jennifer Wild, “‘Are You Afraid of the Cinema?’” AmeriQuests (2015) ‘Are you Afraid of the Cinema?’: Du Cinéma and the Changing Question of Cinephilia and the Avant-Garde (1928-1930) In December 1928, the prolific “editor of the Surrealists,” La Librairie José Corti, launched the deluxe, illustrated journal Du Cinéma: Revue de Critique et de Recherches Cinématographiques.1 Its first issue, indeed its very first page, opened with a questionnaire that asked, “Are you afraid of the cinema?” (Fig. 1, 2) The following paragraphs describing the questionnaire’s logic and critical aims were not penned by the journal’s founding editor in chief, Jean- George Auriol (son of George Auriol, the illustrator, typographer, and managing editor of the fin-de-siècle journal Le Chat Noir); rather, they were composed by André Delons, poet, critic, and member of the Parisian avant-garde group Le Grand Jeu. “This simple question is, by design, of a frankness and a weight made to unsettle you. I warn you that it has a double sense and that the only thing that occupies us is to know which you will choose,” he wrote.2 1. Cover, Du Cinéma, No. 1. Pictured: a still from Etudes Sur Paris (André Sauvage, 1928) 2. Questionnaire, “Are You Afraid of the Cinema?” Du Cinéma, No. 1. 1 Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. 2 André Delons, “Avez-Vous Peur du Cinéma?” Du Cinéma: Revue de Critique et de Recherches Cinématographiques, 1st Series, no.1, (December 1928), reprint edition, ed. Odette et Alain Virmaux (Paris: Pierre Lherminier Editeur, 1979), 3. -

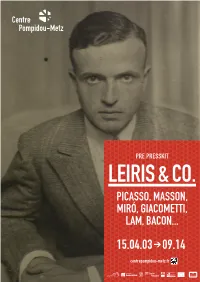

15.04.03 >09.14

PRE PRESSKIT LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... > 15.04.03 09.14 centrepompidou-metz.fr CONTENTS 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW ......................................................................... 2 2. EXHIBITION LAYOUT ............................................................................ 4 3. MICHEL LEIRIS: IMPORTANT DATES ...................................................... 9 4. PRELIMINARY LIST OF ARTISTS ........................................................... 11 5. VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ................................................................... 12 PRESS CONTACT Noémie Gotti Communications and Press Officer Tel: + 33 (0)3 87 15 39 63 Email: [email protected] Claudine Colin Communication Diane Junqua Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 Mél : [email protected] Cover: Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris © The Estate of Francis Bacon / All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris 2014 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 03.04 > 14.09.15 GALERIE 3 At the crossroads of art, literature and ethnography, this exhibition focuses on Michel Leiris (1901-1990), a prominent intellectual figure of 20th century. Fully involved in the ideals and reflections of his era, Leiris was both a poet and an autobiographical writer, as well as a professional -

Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie 2003

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie 2003 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12795 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen: Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2003 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 17). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12795. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0017_03.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Kiel: Berichte und Papiere 17, 1999: Sound. ISSN 1615-7060. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff. Letzte Änderung: 21.9.2008. URL der Hamburger Ausgabe: .http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0017_03.pdf Sound: Eine Arbeitsbibliographie Hans J. Wulff Stille und Schweigen. Themenheft der: Navigatio- Akemann, Walter (1931) Tontechnik und Anwen- nen: Siegener Beiträge zur Medien- und Kulturwis- dung des Tonkoffergerätes. In: Kinotechnik v. 5.12. senschaft 3,2, 2003. 1931, pp. 444ff. Film- & TV-Kameramann 57,9, Sept. 2008, pp. 60- Aldred, John (1978) Manual of sound recording. 85: „Originalton“. 3rd ed. :Fountain Press/Argus Books 1978, 372 pp. Aldred, John (1981) Fifty years of sound. American Cinematographer, Sept. 1981, pp. 888-889, 892- Abbott, George (1929) The big noise: An unfanati- 897.