Preuzmite Časopis U PDF Formatu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

Alberto Giacometti: a Biography Sylvie Felber

Alberto Giacometti: A Biography Sylvie Felber Alberto Giacometti is born on October 10, 1901, in the village of Borgonovo near Stampa, in the valley of Bregaglia, Switzerland. He is the eldest of four children in a family with an artistic background. His mother, Annetta Stampa, comes from a local landed family, and his father, Giovanni Giacometti, is one of the leading exponents of Swiss Post-Impressionist painting. The well-known Swiss painter Cuno Amiet becomes his godfather. In this milieu, Giacometti’s interest in art is nurtured from an early age: in 1915 he completes his first oil painting, in his father’s studio, and just a year later he models portrait busts of his brothers.1 Giacometti soon realizes that he wants to become an artist. In 1919 he leaves his Protestant boarding school in Schiers, near Chur, and moves to Geneva to study fine art. In 1922 he goes to Paris, then the center of the art world, where he studies life drawing, as well as sculpture under Antoine Bourdelle, at the renowned Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He also pays frequent visits to the Louvre to sketch. In 1925 Giacometti has his first exhibition, at the Salon des Tuileries, with two works: a torso and a head of his brother Diego. In the same year, Diego follows his elder brother to Paris. He will model for Alberto for the rest of his life, and from 1929 on also acts as his assistant. In December 1926, Giacometti moves into a new studio at 46, rue Hippolyte-Maindron. The studio is cramped and humble, but he will work there to the last. -

Michele Greet - Inventing Wilfredo Lam: the Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation

Michele Greet - Inventing Wilfredo Lam: The Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation Back to Issue 5 Inventing Wifredo Lam: The Parisian Avant-Garde's Primitivist Fixation Michele Greet © 2003 "It is — or it should be — a well-known fact that a man hardly owes anything but his physical constitution to the race or races from which he has sprung." 1 This statement made by art critic Michel Leiris could not have been further from the truth when describing the social realities that Wifredo Lam experienced in France in the late 1930s. From the moment he arrived in Paris on May 1, 1938, with a letter of introduction to Pablo Picasso given to him by Manuel Hugué, prominent members of the Parisian avant-garde developed a fascination with Lam, not only with his work, but more specifically with how they perceived race to have shaped his art. 2 Two people in particular took an avid interest in Lam—Picasso and André Breton—each mythologizing him order to validate their own perceptions of non- western cultures. This study will examine interpretations of Lam and his work by Picasso, Breton and other members of the avant-garde, as well as Lam's response to the identity imposed upon him. ******* In 1931, the Colonial Exposition set the mood for a decade in which France asserted its hegemony – in the face of Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and Fascist Italy – through a conspicuous display of control over its colonial holdings. The exposition portrayed the colonies as a pre-industrial lost arcadia, occupied by noble savages who were untouched by the industrial advances of the western world. -

Drawing Surrealism Didactics 10.22.12.Pdf

^ Drawing Surrealism Didactics Drawing Surrealism is the first-ever large-scale exhibition to explore the significance of drawing and works on paper to surrealist innovation. Although launched initially as a literary movement with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, surrealism quickly became a cultural phenomenon in which the visual arts were central to envisioning the world of dreams and the unconscious. Automatic drawings, exquisite corpses, frottage, decalcomania, and collage are just a few of the drawing-based processes invented or reinvented by surrealists as means to tap into the subconscious realm. With surrealism, drawing, long recognized as the medium of exploration and innovation for its use in studies and preparatory sketches, was set free from its associations with other media (painting notably) and valued for its intrinsic qualities of immediacy and spontaneity. This exhibition reveals how drawing, often considered a minor medium, became a predominant mode of expression and innovation that has had long-standing repercussions in the history of art. The inclusion of drawing-based projects by contemporary artists Alexandra Grant, Mark Licari, and Stas Orlovski, conceived specifically for Drawing Surrealism , aspires to elucidate the diverse and enduring vestiges of surrealist drawing. Drawing Surrealism is also the first exhibition to examine the impact of surrealist drawing on a global scale . In addition to works from well-known surrealist artists based in France (André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, among them), drawings by lesser-known artists from Western Europe, as well as from countries in Eastern Europe and the Americas, Great Britain, and Japan, are included. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Du Cinéma and the Changing Question of Cinephilia and the Avant-Garde (1928-1930)

Jennifer Wild, “‘Are You Afraid of the Cinema?’” AmeriQuests (2015) ‘Are you Afraid of the Cinema?’: Du Cinéma and the Changing Question of Cinephilia and the Avant-Garde (1928-1930) In December 1928, the prolific “editor of the Surrealists,” La Librairie José Corti, launched the deluxe, illustrated journal Du Cinéma: Revue de Critique et de Recherches Cinématographiques.1 Its first issue, indeed its very first page, opened with a questionnaire that asked, “Are you afraid of the cinema?” (Fig. 1, 2) The following paragraphs describing the questionnaire’s logic and critical aims were not penned by the journal’s founding editor in chief, Jean- George Auriol (son of George Auriol, the illustrator, typographer, and managing editor of the fin-de-siècle journal Le Chat Noir); rather, they were composed by André Delons, poet, critic, and member of the Parisian avant-garde group Le Grand Jeu. “This simple question is, by design, of a frankness and a weight made to unsettle you. I warn you that it has a double sense and that the only thing that occupies us is to know which you will choose,” he wrote.2 1. Cover, Du Cinéma, No. 1. Pictured: a still from Etudes Sur Paris (André Sauvage, 1928) 2. Questionnaire, “Are You Afraid of the Cinema?” Du Cinéma, No. 1. 1 Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. 2 André Delons, “Avez-Vous Peur du Cinéma?” Du Cinéma: Revue de Critique et de Recherches Cinématographiques, 1st Series, no.1, (December 1928), reprint edition, ed. Odette et Alain Virmaux (Paris: Pierre Lherminier Editeur, 1979), 3. -

SYNC EVENT the Ethnographic Allegory of Unsere Afrikareise

SYNC EVENT The Ethnographic Allegory of Unsere Afrikareise Erik Rosshagen Department of Media Studies Master’s Thesis 30 HE credits Cinema Studies Master’s Programme in Cinema Studies Spring 2016 Supervisor: Associate Professor Malin Wahlberg SYNC EVENT The Ethnographic Allegory of Unsere Afrikareise Erik Rosshagen ABSTRACT The thesis aims at a critical reflexion on experimental ethnography with a special focus on the role of sound. A reassessment of its predominant discourse, as conceptualized by Cathrine Russell, is paired with a conceptual approach to film sound and audio- vision. By reactivating experimental filmmaker Peter Kubelka’s concept sync event and its aesthetic realisation in Unsere Afrikareise (Our Trip to Africa, Peter Kubelka, 1966) the thesis provide a themed reflection on the materiality of film as audiovisual relation. Sync event is a concept focused on the separation and meeting of image and sound to create new meanings, or metaphors. By reintroducing the concept and discussing its implication in relation to Michel Chion’s audio-vision, the thesis theorizes the audiovisual relation in ethnographic/documentary film more broadly. Through examples from the Russian avant-garde and Surrealism the sync event is connected to a historical genealogy of audiovisual experiments. With James Clifford’s notion ethnographic allegory Unsere Afrikareise becomes as a case in point of experimental ethnography at work. The sync event is comprehended as an ethnographic allegory with the audience at its focal point; a colonial critique performed in the active process of audio-viewing film. KEYWORDS Experimental Ethnography, Film Sound, Audio-Vision, Experimental Cinema, Documentary, Ethnographic Film CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Demarcation 6 Survey of the field 7 Background 12 Disposition 15 I. -

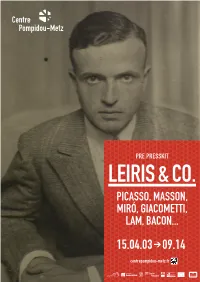

15.04.03 >09.14

PRE PRESSKIT LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... > 15.04.03 09.14 centrepompidou-metz.fr CONTENTS 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW ......................................................................... 2 2. EXHIBITION LAYOUT ............................................................................ 4 3. MICHEL LEIRIS: IMPORTANT DATES ...................................................... 9 4. PRELIMINARY LIST OF ARTISTS ........................................................... 11 5. VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ................................................................... 12 PRESS CONTACT Noémie Gotti Communications and Press Officer Tel: + 33 (0)3 87 15 39 63 Email: [email protected] Claudine Colin Communication Diane Junqua Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 Mél : [email protected] Cover: Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris © The Estate of Francis Bacon / All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris 2014 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 03.04 > 14.09.15 GALERIE 3 At the crossroads of art, literature and ethnography, this exhibition focuses on Michel Leiris (1901-1990), a prominent intellectual figure of 20th century. Fully involved in the ideals and reflections of his era, Leiris was both a poet and an autobiographical writer, as well as a professional -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Cat151 Working.Qxd

Catalogue 151 election from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. Illustrations de Jean Arp. (Collection “Pour Mes Amis.” II.) 23, (5)pp. 35 illustrations and ornaments by Arp (2 full-page), integrated with the text. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies.