Treaty Signatory Views of Treaty Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Edmund Morris Among the Saskatchewan Indians and the Fort Qu'appelle Monument

EDMUND MORRIS AMONG THE SASKATCHEWAN INDIANS AND THE FORT QU'APPELLE MONUMENT By Jean McGill n 1872 the government of Canada appointed Alexander Morris the first Chief Justice of Manitoba. The same year he succeeded A. G. Archibald as Lieu I tenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had already acted as a commissioner of the federal government in negotiating Treaties Nos. 1 and 2 with the Indians of Manitoba. Morris was com missioned in 1873 to carry on negotiations with Indians of the western plains and some Manitoba Indians not present at the first two treaties. By the time Alexander Morris's term of office had expired in 1877 he had negotiated the signing of Treaties No. 3 (North-West Angle), 4 (Fort Qu'Appelle), 5 (Lake Winnipeg), 6 (Forts Carlton and Pitt), and the Revision of Treaties Nos. 1 and 2. Morris later documented the meetings, negotiations, and wording of all of the treaties completed prior to 1900 in a book entitled The Treaties of Canada with the Indians ofManitoba and the North west Territories which was published in 1888. He returned to Toronto with his family and later was persuaded to run for office in the Ontario legislature where he represented Toronto for a number of years. Edmund Morris, youngest of a family of eleven, was born two years before the family went to Manitoba. Indian chiefs and headmen in colourful regalia frequently came to call on the Governor and as a child at Government House in Winnipeg, Edmund was exposed to Indian culture for the Indians invariably brought gifts, often for Mrs. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details File:///T:/Uofrpress/Encyclopedia of SK - Archived/Esask-Uregina-Ca/Entr

The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details file:///T:/uofrpress/Encyclopedia of SK - Archived/esask-uregina-ca/entr... BROWSE BY SUBJECT ENTRY LIST (A-Z) IMAGE INDEX CONTRIBUTOR INDEX ABOUT THE ENCYCLOPEDIA SEARCH DEWDNEY, EDGAR (1835–1916) Welcome to the Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. For assistance in Edgar Dewdney was born in Bideford, Devonshire, England exploring this site, please click here. on November 5, 1835, to a prosperous family. Arriving in Victoria in the Crown Colony of Vancouver Island in May 1859 during a GOLD rush, he spent more than a decade surveying and building trails through the mountains on the If you have feedback regarding this mainland. In 1872, shortly after British Columbia’s entry entry please fill out our feedback into Confederation, he was elected MP for Yale and form. became a loyal devotee of John A. Macdonald and the Conservative Party. In Parliament he pursued the narrow agenda of getting the transcontinental railway built with the terminal route via the Fraser Valley, where he happened to have real estate interests. In 1879 Dewdney became Indian commissioner of the Edgar Dewdney. North-West Territories (NWT) with the immediate task of Saskatchewan Archives averting mass starvation and unrest among the First Board R-B48-1 Nations following the sudden disappearance of the buffalo. Backed by a small contingent of Indian agents and Mounted Police, he used the distribution of rations as a device to impose state authority on the First Nations population. Facing hunger and destitution, First Nations people were compelled to settle on reserves, adopt agriculture and send their children to mission schools. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

Shared with You Here

Winged moccasins Winged Words by Margaret Complin I wish to thank the Editors 'Lohose en couragement made this booklet possible. perance, the first post of the Qu'Appelle of which any record appears to bt. available, was built in 1783 by a Nor'wester, Robert Grant. "There is eviden ce that the Hudson's Bay also had sent men from the Assiniboine to the Mis souri about this time," says Lawrence J. Burpee in "The Search for the ' 'Vestern Sea," but neither names nor dates are now extant." Brandon House on the Assiniboine, about seventeen m iles below the city of Brandon, was built by the Company in 1794. Two years later the post a t P ortage la P rairie (the site of La Verendrye's Fort la R eine) was est ablished. According to Dr. Bryce it was about 1799 that the Company took possession of the Assini boine district. The Swan River count ry, w hich later became one of the most important districts of the Northern Department of Rupert's Land, is associated with the name of Daniel Harmon, the Nor'west er, who arrived in the district in 1800. Harmon spent over three years a t Fort Alexandria and various post s in the district, and we learn from his journal that in 1804 he was at Lac la Peche (probably what we t oday call the Quill Lakes). On March 1st he w as at Last Mountain Lake, and by Sunday, 11th, had reached the banks of Cata buy se pu (the River that Calls). -

Mikisew Cree Submission

Mikisew Cree First Nation Submission October 1, 2012 In the Matter of Energy Resources Conservation Board Application No. 1554388 And In the Matter of Alberta Environment Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act Application No. 005-00153125, 006-0015325 And In the Matter of Water Act File No. 00186157 And In the Matter of Fisheries and Oceans Canada Section 35(2) Authorization Application PROWSE CHOWNE LLP JANES FREEDMAN KYLE LAW CORPORATION Donald P. Mallon, Q.C. Robert Freedman Mark Gustafson Suite 1300, 10020 101 A Avenue 816 - 1175 Douglas Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 3G2 Victoria, British Columbia V8W 2E1 Phone: (780) 439-7171 Phone: (250) 405-3460 Fax: (780) 439-0475 Fax: (250) 381-8567 E-mail: Email: MIKISEW CREE FIRST NATION SUBMISSION ERCB APPLICATION NO. 1554388 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 II. DESCRIPTION OF INTERVENERS ..................................................................... 7 III. REASONS FOR INTERVENTION ........................................................................ 9 IV. REQUESTED DISPOSITION AND REASONS .................................................. 12 V. FACTS TO BE SHOWN IN EVIDENCE ............................................................. 14 VI. EFFORTS MADE BY THE PARTIES TO RESOLVE THE MATTER .............. 16 VII. NATURE AND SCOPE OF INTENDED PARTICIPATION .............................. 17 VII. APPENDIX ........................................................................................................... -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

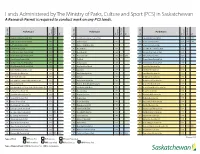

In Saskatchewan

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

Mikisew Cree Submission

Mikisew Cree First Nation Submission October 1, 2012 In the Matter of Energy Resources Conservation Board Application No. 1554388 And In the Matter of Alberta Environment Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act Application No. 005-00153125, 006-0015325 And In the Matter of Water Act File No. 00186157 And In the Matter of Fisheries and Oceans Canada Section 35(2) Authorization Application PROWSE CHOWNE LLP JANES FREEDMAN KYLE LAW CORPORATION Donald P. Mallon, Q.C. Robert Freedman Mark Gustafson Suite 1300, 10020 101 A Avenue 816 - 1175 Douglas Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 3G2 Victoria, British Columbia V8W 2E1 Phone: (780) 439-7171 Phone: (250) 405-3460 Fax: (780) 439-0475 Fax: (250) 381-8567 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] [email protected] MIKISEW CREE FIRST NATION SUBMISSION ERCB APPLICATION NO. 1554388 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 II. DESCRIPTION OF INTERVENERS ..................................................................... 7 III. REASONS FOR INTERVENTION ........................................................................ 9 IV. REQUESTED DISPOSITION AND REASONS .................................................. 12 V. FACTS TO BE SHOWN IN EVIDENCE ............................................................. 14 VI. EFFORTS MADE BY THE PARTIES TO RESOLVE THE MATTER .............. 16 VII. NATURE AND SCOPE OF INTENDED PARTICIPATION .............................. 17 VII. APPENDIX ........................................................................................................... -

JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times

Thomas H. B. Symons Desmond Morton Donald Wright Bob Rae E. A. Heaman Patrice Dutil Barbara Messamore James Daschuk A-HISTORICAL Look at JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times Summer 2015 Introduction 3 Macdonald’s Makeover SUMMER 2015 Randy Boswell John A. Macdonald: Macdonald's push for prosperity 6 A Founder and Builder 22 overcame conflicts of identity Thomas H. B. Symons E. A. Heaman John Alexander Macdonald: Macdonald’s Enduring Success 11 A Man Shaped by His Age 26 in Quebec Desmond Morton Patrice Dutil A biographer’s flawed portrait Formidable, flawed man 14 reveals hard truths about history 32 ‘impossible to idealize’ Donald Wright Barbara Messamore A time for reflection, Acknowledging patriarch’s failures 19 truth and reconciliation 39 will help Canada mature as a nation Bob Rae James Daschuk Canadian Issues is published by/Thèmes canadiens est publié par Canada History Fund Fonds pour l’histoire du Canada PRÉSIDENT/PResIDENT Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens is a quarterly publication of the Association for Canadian Jocelyn Letourneau, Université Laval Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. INTRODUCTION PRÉSIDENT D'HONNEUR/HONORARY ChaIR Canadian Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by the ACS is published in both The Hon. Herbert Marx French and English. All other articles are published in the language in which they are written. SecRÉTAIRE DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE ET TRÉSORIER/ MACDONALd’S MAKEOVER FRENch-LaNGUAGE SecRETARY AND TReasURER Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University the ACS. -

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early