Thumbnail, and Removed It, Taking Care to Provide Enough of a Muddy Bed for His Precious Cargo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Heart Beating Hard

A HEART BEATING HARD A HEART BEATING HARD Lauren Foss Goodman University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © 2015 by Lauren Foss Goodman All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/tfcp.13240726.0001.001 ISBN 978-0-472-03616-5 (paper : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12097-0 (e-book) For Mom and Dad 1. MARJORIE Ma? 1 2. MARGIE Margie started as a suggestion. A frustration. A night out. A drink. A lot of drinks. A thin-lipped smile and some small talk about the Sox. A beer-cold hand on the inside of a soft warm thigh. A laugh, a nod. A locked bathroom stall and a skirt hiked up high. A hand pulling hair. A space, filled. A need. A cry. A release. A disappointment. Margie started there in that small empty place and there single-celled Margie started to divide and divide and divide. Unseen, unknown Margie, what was Margie before she was Margie, burrowed and billowed and became. Swimming in the warm dark waters where we all live before we live, growing skin to con- tain, lungs to breathe, a heart to beat. -

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

SPIDER-MAN: INTO THE SPIDER-VERSE Screenplay by Phil Lord and Rodney Rothman Story by Phil Lord Dec. 3, 2018 SEQ. 0100 - THE ALTERNATE SPIDER-MAN “TAS” WE BEGIN ON A COMIC. The cover asks WHO IS SPIDER-MAN? SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) Alright, let’s do this one last time. My name is Peter Parker. QUICK CUTS of a BLOND PETER PARKER Pulling down his mask...a name tag that reads “Peter Parker”...various shots of Spider-Man IN ACTION. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) I was bitten by a radioactive spider and for ten years I’ve been the one and only Spider-Man. I’m pretty sure you know the rest. UNCLE BEN tells Peter: UNCLE BEN (V.O.) With great power comes great responsibility. Uncle Ben walks into the beyond. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) I saved a bunch of people, fell in love, saved the city, and then I saved the city again and again and again... Spiderman saves the city, kisses MJ, saves the city some more. The shots evoke ICONIC SPIDER-MAN IMAGES, but each one is subtly different, somehow altered. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) And uh... I did this. Cut to Spider-Man dancing on the street, exactly like in the movie Spider-Man 3. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) We don’t really talk about this. A THREE PANEL SPLIT SCREEN: shots of Spider-Man’s “products”: SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) Look, I’m a comic book, I’m a cereal, did a Christmas album. I have an excellent theme song. (MORE) 2. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) (CONT'D) And a so-so popsicle. -

Hip-Hop Realness and the White Performer Mickey Hess

Critical Studies in Media Communication Vol. 22, No. 5, December 2005, pp. 372Á/389 Hip-hop Realness and the White Performer Mickey Hess Hip-hop’s imperatives of authenticity are tied to its representations of African-American identity, and white rap artists negotiate their place within hip-hop culture by responding to this African-American model of the authentic. This article examines the strategies used by white artists such as Vanilla Ice, Eminem, and the Beastie Boys to establish their hip- hop legitimacy and to confront rap music’s representations of whites as socially privileged and therefore not credible within a music form where credibility is often negotiated through an artist’s experiences of social struggle. The authenticating strategies of white artists involve cultural immersion, imitation, and inversion of the rags-to-riches success stories of black rap stars. Keywords: Hip-hop; Rap; Whiteness; Racial Identity; Authenticity; Eminem Although hip-hop music has become a global force, fans and artists continue to frame hip-hop as part of African-American culture. In his discussion of Canadian, Dutch, and French rap Adam Krims (2000) noted the prevailing image of African-American hip-hop as ‘‘real’’ hip-hop.1 African-American artists often extend this image of the authentic to frame hip-hop as a black expressive culture facing appropriation by a white-controlled record industry. This concept of whiteÁ/black interaction has led white artists either to imitate the rags-to-riches narratives of black artists, as Vanilla Ice did in the fabricated biography he released to the press in 1990, or to invert these narratives, as Eminem does to frame his whiteness as part of his struggle to succeed as a hip-hop artist. -

Social Media Poems 2019 Simeon Berry

Social Media Poems 2019 Simeon Berry Contents A Vision for the Coming Year (Joanna Penn Cooper) ................................................................................. 1 Triage (Adrian Blevins) ................................................................................................................................ 3 In Praise of Wax (Landon Godfrey) ............................................................................................................. 4 August (Sandra Beasley) ............................................................................................................................... 5 Oracle for the Violin’s Daughter (Erica Wright) .......................................................................................... 6 In the Dream (Jenny Johnson) ...................................................................................................................... 7 Our Lady of the Hair Cuttery (B.K. Fischer) ................................................................................................ 9 Kowalski: A Historiography (Sean Thomas Dougherty) ............................................................................ 10 The Cartoonist in Hell (Paul Guest) ............................................................................................................ 11 A Simple Lesson on the Buried Spirit (Lisa Olstein) ................................................................................. 12 Writing Poetry Is Like Fielding Ground Balls (Tara Skurtu) .................................................................... -

D Haen Thesis (731.9Kb)

CHASING RABBITS: A CONTEMPORARY WAR NOVEL by Dennis R. Haen A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 April 2013 PROVOST COMMITTf[EPPRVAL AND VICE CHANCELLOR . Advisor ~~=-~~~~~~---------~ - k/2L- ___'f--'-!_~__ ..L-b_'3___ Date Approved Date Approved _~~:"-=-J~~M~Q_~<,~Member FORMA T APPROVAL ~ /2..211 j\ Date APp~::L _~::....!.--~___~+t---=- __~-,,---=---~ __ Member ~ · a ~ 1# 12> Date Approved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Critical Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 1 Chasing Rabbits………………………………………………………………………. 23 One…………………………………………………………………………………… 24 Two…………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Four…………………………………………………………………………………… 56 Six…………………………………………………………………………………….. 79 Seven…………………………………………………………………………………. 96 Eight…………………………………………………………………………………. 111 Nine………………………………………………………………………………….. 129 Twelve……………………………………………………………………………….. 145 Sixteen……………………………………………………………………………….. 170 Thirty………………………………………………………………………………… 200 Thirty-Two…………………………………………………………………………… 216 Works Cited and Referenced...……………………………………………………….. 231 ii. 1 CRITICAL INTRODUCTION The history of the American war novel can be traced back the earliest conflicts that defined the United States. The novel has been an ideal genre for demonstrating the long process of war, the string of hardships it can place on a soldier, the sudden and cumulative changes it can make on a human being, and the specifics of location, climate, culture, and military technology -

The Suspicious Fish

sUsPICIOUS FISH VERDUN ELEMENTARY AFTER SCHOOL ARTS and literacy PROGRAM VOLUME 6, 2012-2013 front cover artist Hayley Rodriguez-Roy back cover artists Hayley Rodriguez-Roy and Kaytlin Staples Edited by Gary Purcell WAIT! BEFORE YOU BEGIN FEASTING ON ALL THESE GREAT WORDS… We’ve been wondering if a single word in the English language exists that accurately expresses awe, fear, anger, tummy pain, snot-spouting laughter, inspiration, reflection, anticipation, and for some strange reason; itchy elbows? If such a word does exist, we don’t know it but we started thinking as we put this anthology together that such a word should. We thought about this as we sorted through piles and piles of finely crafted tales about ghosts and frogs, gross bugs, tattle tales, aliens, television shows, doughnuts, leprechauns, teachers, rats, puppies, parents, and ears. Yes, we asked them to write about ears and what they gave us is something that will keep us up nights for the rest of our lives. We never would have thought they would have come with so much about the two things that rest on the sides of a head. See, there you go, just the two things that rest on the sides of a head, that what we thought about them, but not them, not the authors. They really made us think about ears. Where were we? Oh yes, we were looking for a single word to describe everything that you get to read and smile and laugh and gasp over in this book. We also forgot to mention all the fear and mayhem that the writers instilled throughout the writing of these tales. -

Just a Quickie

1 MATURE A UDIENCES ONLY 2 2008 | Honors Composition Short Shorts For Mr. Webb, We all know how much you like your Quickies Even though you had nothing to do with the creation of this Magazine 3 EDITOR IN CHIEF: Heather Crume CO-EDITORS: Christina Mudrick , Meaghan Kingsley-Teem, Tracy Selfridge, Hillary Lucas, Heather Allison , Kristen lee, Johana Shea, Danielle Jespersen WRITERS: Heather Crume, Meaghan Kingsley-Teem, Christina Mudrick, Hillary Lucas, Tracy Selfridge, Kristen lee, , Johana Shea, Danielle Jespersen, Heather Allison , Nelson Vazquez, Marissa Dunaway, Russell peck, Kenny Sarisky, Nikki Young, Erik Engvall, Jawsem Al- Hashash, Brittney Woods, Richard Gilbert, Stephanie Wright, Jessica Geiss, Christa Brooks, Katie Eng ART/PHOTOGRAPH CONTRIBUTIONS BY: Kristen Lee, Meaghan Kingsley-Teem, Nikki Young, Danielle Jespersen, Hillary Lucas, Heather Allison, Tracy Selfridge, Danny Mao POETRY BY: Meaghan Kingsley-Teem, Zander Andrus COVER BY: Heather Allison INSIDE COVER BY: Heather Crume 4 QUICKIES: Heather Crume, Jack’s Offense . 6-7 Nelson Vazquez, Murder Killed . 9-10 Marissa Dunaway, Jack . 11-12 Christina Mudrick, 1941 . 14-17 Meaghan Kingsley-Teem, A New Day . .19-21 Russell Peck, Empty . 24-26 Kenny Sarisky . 27-28 Heather Allison, Graziella’s Visitor . .29-31 Erik Engvall, Before the Red Light Changes . .33 Tracy Selfridge, Aischune . 34-36 Jawsem Al-Hashash, Control . .37-38 Danielle Jesperson, Punishment . .39-42 Brittney Woods, The Wreckage . .44-45 Richard Gilbert, Nothing There . 47-48 Stephanie Wright, Irene . 50-53 Jessica Geiss, Smile . .54-55 Johana Shea, Judgment . 58-61 Hillary Lucas, Blind Jealousy . 63-64 Kristen Lee, Photograph of the Best Times . 66-68 Christa Brooks, Who Made the Mess? . -

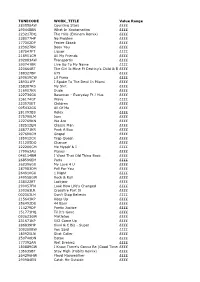

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

The Dynamics of Literacy Acquisition and Learning: Focusing on Gifted Learners in a Language Arts Collaborative Class

THE DYNAMICS OF LITERACY ACQUISITION AND LEARNING: FOCUSING ON GIFTED LEARNERS IN A LANGUAGE ARTS COLLABORATIVE CLASS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Linda Lee Kelley, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Caroline Clark, Co-Adviser ________________________ Co-Adviser Professor Barbara Lehman, Co-Adviser ________________________ Professor George Newell Co-Adviser Graduate Program in Education ABSTRACT This case-study research focuses on the dynamics of literacy acquisition and learning in a language arts-art collaborative class addressing the curricular needs eighth- grade students identified as gifted and/or highly motivated. Basing the curricular design on the social situatedness of literacies, three teacher research participants developed a framework for exploring literacies first from student research participants’ personal perspectives, then extending observations and explorations to other diverse cultures. Data include written texts, art pieces, dialogic interviews, reflective journal entries, class discussions and observations, and audio/videotapes. All provide descriptive information that served as a basis for analyses addressing questions related to explaining the dynamics that impact doing writing. Conclusions indicate that curricular design based on relevant, purposeful questions provides cohesiveness, consequently promoting effective literacy instruction. Attention to instructional scaffolding with particular emphasis on teacher-student collaboration emerges as a fundamental framework for developing appropriately challenging differentiation in literacy acquisition and learning—beyond minimal proficiencies. ii Dedicated to Robbie and Andrew iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank my advisers, Caroline Clark and Barbara Lehman, for their encouragement and consistent support that served to challenge my thinking and guide its organization. -

Princess Charlotte and the Lake Dwellers

Princess Charlotte and the Lake Dwellers Written by Harry Jonathan Chong Hello, Jell-O Once upon a time in a land far away, was a race of proud people. They were conquerors who traveled from place to place. Their prosperity unsurpassed; they went about plundering and pillaging villages, without a thought, living off the fruits and labor of others. The Malgelions, as they were known, had access to the most powerful weapons. They had the best of the best of the best; the best swords, the best shields, the best boots from the butts of beasts who could not bear the burden of the overbearing barbarians. Nothing but the finest for the Malgelions, they took what they wanted and stole what they needed. But of course, one cannot go about living a life of hedonism without upsetting the locals. “Oh,” said Triskut the Mighty to his army, “we have done well. It is time to reward ourselves. Men, take what you will. Food, wine, women, it is yours. And for the women in the army, you may substitute the men for women. Let us go and ransack. The weak defenders of this village have vanquished under our mighty fists. It is ours for the taking!” As the men of Triskut’s army disperse, a haggardly lady appears. “Stop,” she commands with her big bumpy nose wiggling side to side, “you are not entitled to that which is not your own. You are not entitled to that which has not been created under the labor of your own hands. Leave this place and never come back or I will curse your people.” Triskut laughs. -

Elite Karaoke Draft by Artist 2 Pistols Feat

Elite Karaoke Draft by Artist 2 Pistols Feat. Ray J You Know Me (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Pistols Feat. T-Pain & Tay Bartender Dizm Blackout She Got It Other Side 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Renegade Jucxi D 10 Years Careless Whisper Actions & Motives 2 Unlimited Beautiful No Limit Drug Of Choice Twilight Zone Fix Me 20 Fingers Fix Me (Acoustic) Short Dick Man Shoot It Out 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro 10,000 Maniacs Boomin & Travis Scott Because The Night Ghostface Killers Candy Everybody Wants 2Pac Like The Weather Changes More Than This Dear Mama These Are The Days How Do You Want It Trouble Me I Get Around 100 Proof (Aged In Soul) So Many Tears Somebody's Been Sleeping Until The End Of Time 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre Cruella De Vil California Love 10cc 2Pac Feat. Elton John Dreadlock Holiday Ghetto Gospel Good Morning Judge 2Pac Feat. Eminem I'm Not In Love One Day At A Time The Things We Do For Love 2Pac Feat. Eric Williams Things We Do For Love Do For Love 112 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dance With Me Runnin' Peaches & Cream 3 Doors Down Right Here For You Away From The Sun U Already Know Be Like That 112 Feat. Ludacris Behind Those Eyes Hot & Wet Citizen Soldier 112 Feat. Super Cat Dangerous Game Na Na Na Duck & Run 12 Gauge Every Time You Go Dunkie Butt Going Down In Flames 12 Stones Here By Me Arms Of A Stranger Here Without You Far Away It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Shadows Kryptonite We Are One Landing In London 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

RESILIENT YOUTH INA VIOLENT M O WORLD M CD

-- - -- -', If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. RESILIENT YOUTH INA VIOLENT M o WORLD M CD . New Perspectives LO and Practices Published by the COLLABORATIVE for SCHOOL COUNSELING and SUPPORT SERVICES 156303 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been ~1'1~rative for School Colllselina and Support Services to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. NCJRS Preface and Acknowledgments SEP 2'l t995 his monograph is a record of Resilient Youth in a which we earnestly commend for its strong commitment to Violent World: New Perspectives and Practices, a a broad range of efforts aimed at understanding and pre summer Institute that took place at the Harvard venting violence in our world. The Foundation has also T Graduate School of Education from July 7-12, helped to support follow-up of participating teams during 1994. The program, designed by the Collaborative for the present academic year. Metropolitan Life has focused its School Counseling and Support Services, was intended to last two national teacher surveys on the issue of violence. serve school counselors, psychologists, social workers, We are especially grateful to Virginia Millan of the Metro nurses, teachers, health educators, and administrators - politan Life Foundation for her interest, patience, support, the same kind of audience that attended the Collaborative's and encouragement.