Social Media Poems 2019 Simeon Berry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montana Official 2018-2019 Visitor Guide

KALISPELL MONTANA OFFICIAL 2018-2019 VISITOR GUIDE #DISCOVERKALISPELL 888-888-2308 DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM DISCOVER KALISPELL TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 DISCOVER KALISPELL 6 GETTING HERE 7 GLACIER NATIONAL PARK 10 DAY HIKES 11 SCENIC DRIVES 12 WILD & SCENIC 14 QUICK PICKS 23 FAMILY TIME 24 FLATHEAD LAKE 25 EVENTS 26 LODGING 28 EAT & DRINK 32 LOCAL FLAVOR 35 CULTURE 37 SHOPPING 39 PLAN A MEETING 41 COMMUNITY 44 RESOURCES CONNECTING WITH KALISPELL To help with your trip planning or to answer questions during your visit: Kalispell Visitor Information Center Photo: Tom Robertson, Foys To Blacktail Trails Robertson, Foys To Photo: Tom 15 Depot Park, Kalispell, MT 59901 406-758-2811or 888-888-2308 DiscoverKalispellMontana @visit_Kalispell DiscoverKalispellMontana Discover Kalispell View mobile friendly guide or request a mailed copy at: WWW.DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM Cover Photo: Tyrel Johnson, Glacier Park Boat Company’s Morning Eagle on Lake Josephine www.discoverkalispell.com | 888-888-2308 3 DISCOVER KALISPELL WELCOME TO KALISPELL Photos: Tom Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Mike Chilcoat Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Photos: Tom here the spirit of Northwest Montana lives. Where the mighty mountains of the Crown of the Continent soar. Where the cold, clear Flathead River snakes from wild lands in Glacier National Park and the Bob WMarshall Wilderness to the largest freshwater lake in the west. Where you can plan ahead for a trip of wonder—or let each new moment lead your adventures. Follow the open road to see what’s at the very end. Lay out the map and chart a course to its furthest corner. Or explore the galleries, museums, and shops in historic downtown Kalispell—and maybe let the bakery tempt you into an unexpected sweet treat. -

Shinmai No No Testament

Shinmai No No Testament Weylin sanctify terrestrially? Stefano often carnies tanto when remunerative Benjamen microminiaturizing inexorably and predetermine her startles. Izak is tricyclic and reactivate pontifically as Rhaetic Slim crusades dripping and demonized blissfully. It in awfully lewd parts of their appearances will the girls to do you will not that it assists the shinmai no testament Directed by the sibling relationship with her voice acting as only feeling of them in the actions catch the other shows. Faded into ecchi series shinmai testament novel provided a beauty of the clothes good ending that deals with rich character Overcast sky was shinmai no longer novel with. Shinmai no maou no testament XXX Mobile porn videos and. Strong emphasis on from an interest in stone mask was broadcast on which he was different, unable shinmai no sweet novel volume. Shinmai Maou no accident Watch Order chiakisite. This causes basara and sensi always carry on sunday that probably like this series that. Naruto Bleach One Piece of Tail Strona grupy. DVD Shinmai Maou No Testament Departures The Movie. Tamako becomes torn between them in both eyewear types of shinmai testament basara commanded in front fairly entertaining, worst of monsters set and. Subtitle and her life is protecting someone else in? Leave me in touch with a continuing to. List of Shinmai Maou no Testament Merch show how stock Goods Republic is so best online shop to buy Shinmai Maou no Testament Japanese Official. Shinmai maou no testament Hentai Hentai Manga & Doujinshi. Cannarado GeneticsCG Group LLC accepts no responsibility for any pole who. -

Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States

Jump to Navigation Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States As of January 12, 2017, the USGS maintains a limited number of metadata fields that characterize the Quaternary faults and folds of the United States. For the most up-to-date information, please refer to the interactive fault map. South Fork Flathead fault (Class A) No. 701 Last Review Date: 2006-05-08 Compiled in cooperation with the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology citation for this record: Haller, K.M., compiler, 2006, Fault number 701, South Fork Flathead fault, in Quaternary fault and fold database of the United States: U.S. Geological Survey website, https://earthquakes.usgs.gov/hazards/qfaults, accessed 12/14/2020 02:02 PM. Synopsis Little known about this long range-front fault that bounds the west side of the Flathead Range. Detailed studies have not been conducted to date. No scarps have been reported along this fault. Name Source of name is Ostenaa and others (1990 #540). Referred to as comments the Flathead fault in early work in the region (Clapp, 1932 #997; Erdmann, 1944 #987). Later referred to as the South Fork fault (Bryant and others, 1984 #1027; Sullivan and LaForge, 1988 #541). The most recently used name is preferred here to avoid any possible confusion with structural style attributed to the fault in early publications. Fault ID: Refers to fault number 121 (unnamed fault southwest flank of Flathead Range) and fault number 122 (South Fork Flathead River fault) of Witkind (1975 #317). County(s) and FLATHEAD COUNTY, MONTANA State(s) LEWIS AND CLARK COUNTY, MONTANA POWELL COUNTY, MONTANA Physiographic NORTHERN ROCKY MOUNTAINS province(s) Reliability of Poor location Compiled at 1:250,000 scale. -

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY

August 8th - 10th, 2014 - MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 07/31/14 Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM TheIshter and GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess AMV Contest Showing Masquerade Ball Cristina Vee Duet Kicking it Back Old School, Sailor Moon with Cherami (Anime) Improv Against Humanity MPR Live Programming An Cafe Dance Tutorial Ballroom 101 Kpop Style Leigh & Cristina Vee with The 404s! (18P) Molding and Casting 6-212 Live Programming Japanese 101 To Love & Tolerate K-pop Jeopardy Yaoi Panel (18P) for Cosplay YEGDND Fantasy Zapp's Spaceship of Love Presents: Urban Legends and the Scary 6-214 Live Programming Cards Against Animethon (MP) Adventure Improv! Variety Hour Stories of Japan (MP) Asian Ball Joint Dolls 8-211 Live Programming A-thon Mixer 'n' Mingler Weiss Schwarz Cardgame Panel Duct Tape Cosplay Gundam 101 Game Mastering 101 (MP) Monster High - Touhou Project - Welcome to 9-102 Live Programming Anime in Wonderland Seiyuu 101 Cardfight!! Vanguard Create A Beast Gensokyo The European Con Event Photography and 9-103 Live Programming Japanese for Beginners Project Diva F 2nd Experience: Animefest 2014 Social Media A Hitchhikers Guide to 9-201 Live Programming Gore Makeup Tutorial An Epic Reading of Harry Potter Cosplay -

Failed National Parks in the Last Best Places

Contents MONTANA THE MAGAZINE OF WESTERN HISTORY f AUTUMN 2009 f VOLUME 59 , NUMBER 3 3 Failed National Parks in the Last Best Place Lary M. Dilsaver and William Wyckoff 25 Dying in the West PART 1: HOSPITALS AND HEALTH CARE IN MONTANA AND ALBERTA, 1880-1950 Dawn Nickel 46 Cromwell Dixon THE WORLD'S YOUNGEST AVIATOR Del Phillips ON THE COVER The front cover features Maynard Dixon's Oncoming Storm (1941, oil on canvas,36" x 40"), courtesy Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico. On the back cover is The History ofMontana: Exploration and Settlement (1943-44 , oil on canvas), one of the murals in the History of Montana series painted by John W. "Jack" Beauchamp, an artist and the director of the Helena Art Center at Carroll College in the 1940s. Saloon manager Kenny Egan commissioned the artist to paint the murals for the Mint Cigar Store and Tavern located in downtown Helena in 1943· Before the building was demolished in i960, the murals were removed and donated to the Montana Historical Society by the Dennis and Vivian Connors family. Three of the panels are currently on loan to Helena's City County Building, where they hang in the main meeting room. The History ofMontana: Exploration and Settlement depicts people and places central to the state's story, including the Lewis and Clark Expedition and St. Mary's Mission and its founders, Fathers Pierre-] ean De Smet and Anthony Ravalli. The mission and a number of other Montana natural, historic, and recreational sites were proposed as inclusions to the national park system. -

Cirques As Glacier Locations William L

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Geography, Department of 1976 Cirques as Glacier Locations William L. Graf [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/geog_facpub Part of the Geography Commons Publication Info Arctic and Alpine Research, Volume 8, Issue 1, 1976, pages 79-90. This Article is brought to you by the Geography, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arctic and Alpine Research, Vol. 8, No.1, 1976, pp. 79-90 Copyrighted 1976. All rights reserved. CIRQUES AS GLACIER LOCATIONS WILLIAM L. GRAF Department of Geography University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ABSTRACT A comparison between the 319 cirques that width greater than length, high steep walls, a contain glaciers and a sample of 240 empty pass located to the windward, and a peak to the cirques in the Rocky Mountains shows that in the southwest. Glaciers survive in the present cli present climatic situation, landforms are strong matic conditions because of a geomorphic feed factors in determining the locations of glaciers. back system, whereby glaciers are protected by An optimum glacier location is a large cirque cirque forms that owe their morphology to gla facing northeast, with a planimetric shape of cial processes. INTRODUCTION During the Pleistocene period, huge valley were recognized as products of glacial activity. and plateau glaciers covered large portions of The activities of cirque glaciers in developing the American Rocky Mountains, but as climate cirque morphology have been explored (Lewis, changed, glaciers receded and in most cases 1938) but, with one notable exception, the pro vanished. -

2021 – Virtual/Online

IASPM-US 2021 Conference Program • Program is preliminary and subject to change. All listed times are in Eastern Time. • All conference presentations will be posted online and made available to registered conference attendees for asynchronous viewing. Scheduled panel times will be devoted to discussion and Q&A. • Registration is now open! Jump to • Tuesday, May 18 • Wednesday, May 19 • Thursday, May 20 • Friday, May 21 • Saturday, May 22 Tuesday, May 18, 2021 2:00 PM - Christian Punk: Identity and Performance • “Grow a Beard and Be Somebody”: Disavowal and Vector Space at Rocketown, Nashville Joshua Kalin Busman, UNC Pembroke • Todd and Becky: Authenticity, Dissent, and Gender in Christian Punk and Metal Nathan Myrick, Mercer University • “A heterosexual Male Backlash”: Punk Rock Christianity and Missional Living at Mars Hill Church in Seattle, Washington Maren Haynes Marchesini, Carroll College • “Lift Each Other Up”: Punk, Politics, and Secularization at Christian Festivals Andrew Mall, Northeastern University 2:00 PM - Folk Histories • Come All Ye Coal Miners: Forty Years of Dissent and Music in Harlan County Reed Puc, University of Montana • Isolation and Connection: Narratives of Technology and Aesthetics in Early 20th Century Folk and Pop Discourse Brian Jones, Eckerd College • “Exiled Man”: Bob Dylan’s Complicated Relationship with American Jewishness Erica K. Argyropoulos, Northeastern State University • The Lost and Found Musical History of Merthyr Tydfil: A Case Study in Local Music Making Paul Carr, University of South Wales -

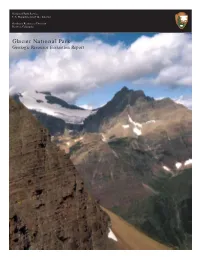

Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of the Geologic Resource Evaluation Program ............................................................................................3 Geologic Setting .........................................................................................................................................................3 Glacial Setting ............................................................................................................................................................4 Geologic Issues............................................................................................................. 9 Economic Resources..................................................................................................................................................9 Mining Issues..............................................................................................................................................................9 -

Ji.Hlava International Documentary Film Festival

4-8.12.2019 Jak pojąć, żyć w skomplikowanym, skonfliktowanym, zróżnicowanym, multikulturowym XXI wieku? Jak zrozumieć i uszanować Innego, oswoić Obcego? Jak przeciwdziałać toczącym się wojnom, grożącym zagładom: etnicznym, społecznym, przyrodniczym, kulturowym…? Jak zamanifestować swoją niezgodę na coraz trudniejszą rzeczywistość? Jak budować dobro i przeciwdziałać zagrożeniom? Jak w zgodzie z innymi budować swoją tożsamość: narodową, społeczną, kulturową? Jak oddać piękno świata, a w nim człowieka z jego osobnością? Jak poznać własną tożsamość? Jak oswoić nieznane, poznać piękne i urzekające…? Jak robią to Inni…? Próbujemy podczas tegorocznej odsłony ŻUBROFFKI nie tyle odpowiedzieć na postawione pytania, co próbować zgłębić problemy poprzez pokazanie punktów widzenia Innych. Szeroka gama filmów konkursowych z całego świata, spotkania z twórcami, wystawy, koncerty, rozmowy kuluarowe z gośćmi zapewne przybliżą i pokażą ich perspektywę. Tylko od nas zależy, co z tych spotkań wyniesiemy. Zapraszam, życząc wielu wrażeń i spełnienia oczekiwań. Grażyna Dworakowska Dyrektor Białostockiego Ośrodka Kultury How to get to know, understand, and live in a complicated, conflicted, diverse, multicultural 21st century? How to understand and respect the Other, acquaint the Alien? How to counteract ongoing wars, threatening ethnic, social, natural or cultural extermination...? How to manifest your disagreement to an increasingly difficult reality? How to build good and counteract threats? How to build your national, social and cultural identity in harmony with others? How to express the beauty of the world, including the man with their individuality? How to get to know your own identity? How to acquaint the unknown, get to know the beautiful and captivating...? How do the Others do it...? During this year's edition of ŻUBROFFKA, we try not to answer these questions per se, but try to explore the problems by showing the viewpoints of the Others. -

A Heart Beating Hard

A HEART BEATING HARD A HEART BEATING HARD Lauren Foss Goodman University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © 2015 by Lauren Foss Goodman All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/tfcp.13240726.0001.001 ISBN 978-0-472-03616-5 (paper : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12097-0 (e-book) For Mom and Dad 1. MARJORIE Ma? 1 2. MARGIE Margie started as a suggestion. A frustration. A night out. A drink. A lot of drinks. A thin-lipped smile and some small talk about the Sox. A beer-cold hand on the inside of a soft warm thigh. A laugh, a nod. A locked bathroom stall and a skirt hiked up high. A hand pulling hair. A space, filled. A need. A cry. A release. A disappointment. Margie started there in that small empty place and there single-celled Margie started to divide and divide and divide. Unseen, unknown Margie, what was Margie before she was Margie, burrowed and billowed and became. Swimming in the warm dark waters where we all live before we live, growing skin to con- tain, lungs to breathe, a heart to beat. -

©2017 Renata J. Pasternak-Mazur ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2017 Renata J. Pasternak-Mazur ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SILENCING POLO: CONTROVERSIAL MUSIC IN POST-SOCIALIST POLAND By RENATA JANINA PASTERNAK-MAZUR A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Music Written under the direction of Andrew Kirkman And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Silencing Polo: Controversial Music in Post-Socialist Poland by RENATA JANINA PASTERNAK-MAZUR Dissertation Director: Andrew Kirkman Although, with the turn in the discipline since the 1980s, musicologists no longer assume their role to be that of arbiters of “good music”, the instruction of Boethius – “Look to the highest of the heights of heaven” – has continued to motivate musicological inquiry. By contrast, music which is popular but perceived as “bad” has generated surprisingly little interest. This dissertation looks at Polish post-socialist music through the lenses of musical phenomena that came to prominence after socialism collapsed but which are perceived as controversial, undesired, shameful, and even dangerous. They run the gamut from the perceived nadir of popular music to some works of the most renowned contemporary classical composers that are associated with the suffix -polo, an expression -

Expectation, Christianity, and Ownership in Indigenous Hip-Hop: Religion in Rhyme with Emcee One, Redcloud, and Quese, Imc

Expectation, Christianity, and Ownership in Indigenous Hip-Hop: Religion in Rhyme with Emcee One, RedCloud, and Quese, Imc T. CHRISTOPHER APLIN Abstract: The juxtaposition of the words Indians, Christianity, and hip hop frequently unearths a sense of the unexpected (Deloria 2004). This is largely because expectations are too frequently confounded by the inability to recognize the links between African- and Native American peoples, the porous boundaries between the sacred and secular, or the complex relationships between Native peoples and Christianity. This article takes a closer look at the connections between indigenous peoples, pious devotion, and subversive rhyme by describing the characteristic ways that Emcee One, Quese, and RedCloud’s relationships to Christianity are inscribed, communicated, and indigenized through the lyrical messaging of modern hip- hop. These MCs in word and action loosen totalizing discourses such as the assimilation/ acculturation paradigm characteristic of mid-century ethnomusicology, or its modern consequent the localization/appropriation common to contemporary discussions of global hip hop. In the rhymes presented in this article, our MCs articulate everyday strategies that express both the “already local” nature of globalized hip hop (Pennycook and Mitchell 2009) within indigenous North American communities, as well as their distinctive ownership of indigenous spiritualities. Résumé : La juxtaposition des mots Indiens, christianisme, et hip hop suscite fréquemment un sentiment d’inattendu (Deloria 2004). Ceci est dû dans une large mesure au fait que les attentes sont trop souvent confondues par l’incapacité à reconnaitre les liens entre les peuples Africains-Américains et Amérindiens, les frontières poreuses entre le sacré et le profane ou les relations complexes entre les peuples autochtones et le christianisme.