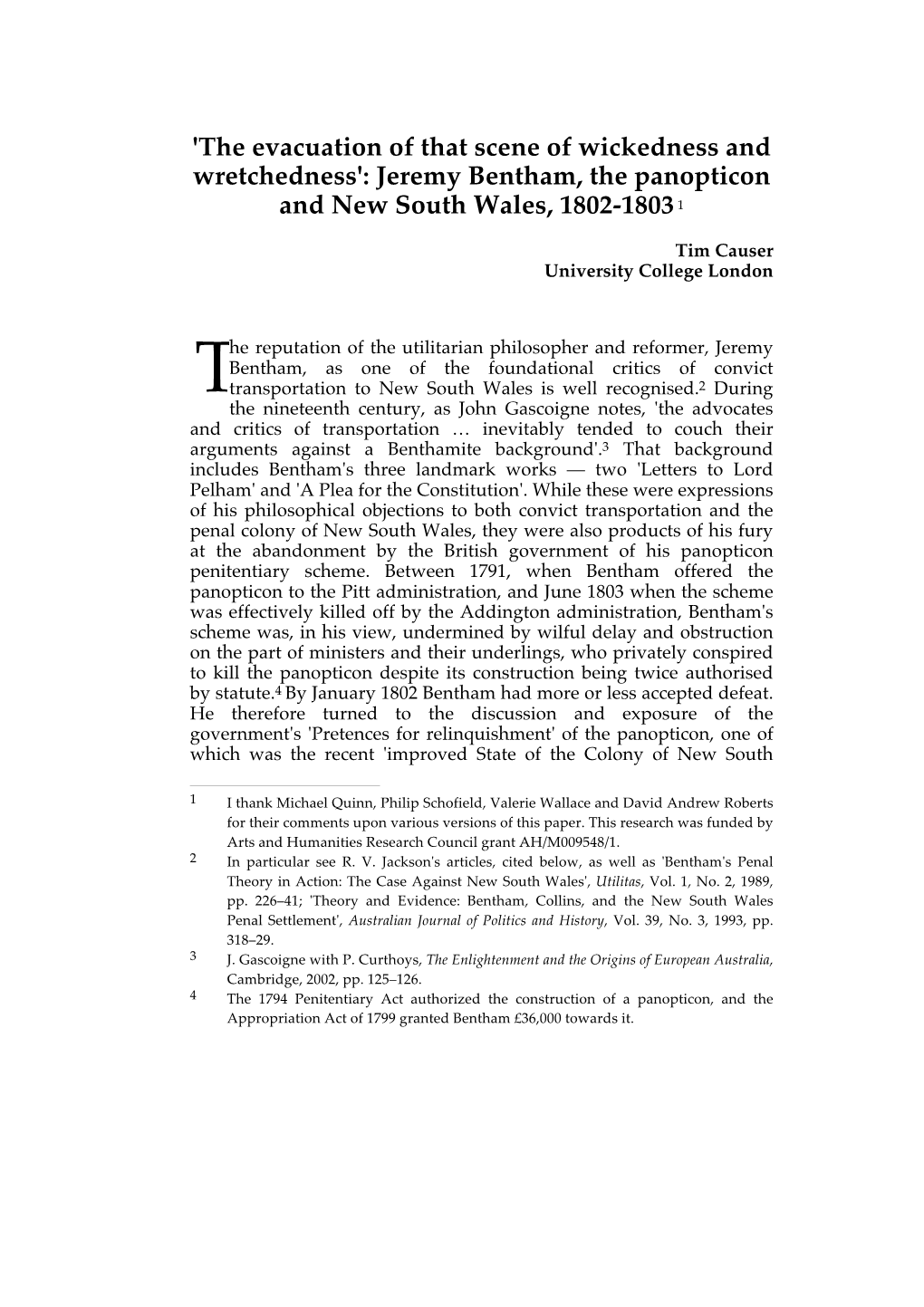

Jeremy Bentham, the Panopticon and New South Wales, 1802-18031

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanticism and Linguistic Theory: William Hazlitt, Language and Literature P.Cm

Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Also by Marcus Tomalin: LINGUISTICS AND THE FORMAL SCIENCES Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory William Hazlitt, Language and Literature Marcus Tomalin Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert © Marcus Tomalin 2009 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publica- tion may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2009 by PALGRAVE macmILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin's Press LLC,175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Clare: Abstract and New Intro In

Citation for published version: Gittings, C & Walter, T 2010, Rest in peace? Burial on private land. in J Sidaway & A Maddrell (eds), Deathscapes: Spaces For Death Dying And Bereavement. Ashgate, Aldershot. Publication date: 2010 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Reproduced here by kind permission of Ashgate. University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Rest in Peace? Burial on Private Land Clare Gittings and Tony Walter Ever since the adoptation of Christianity in the early Middle Ages, it has been normal for Britain’s dead to be buried in churchyards or other Christian burial grounds (Daniell 1998; Jupp and Gitttings 1999). From the mid-nineteenth century, but with earlier examples in Scotland, cemeteries (i.e. formal burial grounds not attached to a church) have supplanted churchyards as the most common place of burial (Rugg 1997), augmented in the twentieth century by cremation (Jupp 2006). Private burial on your own land, rather than in churchyard or cemetery, has been and remains rare in Britain. It is, though, legal. -

Re-Constructing Ideology, Part One: Animadversions of John Horne Tooke on the Origins of Affixes and Non-Designative Words

Re-constructing ideology, Part one: Animadversions of John Horne Tooke on the origins of affixes and non-designative words Fredric Dole~al J Introduction John Home Tooke occupies a unique place in the hi!)tory of Indo-European studies and lexicography - ohlivion: Only rarely in discussions of lndo Europcan linguistics and lexicography does one find a mention of the unre doubtablc, irascible. and scioli~tic champion of comparative and historical language study: but then. why ~hould a sciolist and purveyor of fanciful ety mologies he mentioned at all '? If we acknowledge the widely accepted propo sition that 'linguistics-as-we-know-it' began "1th Franz Bopp. then Home Tooke need not be considered at all. HoweH:r. this proposition can be main tained only by interpreting the history of linguistics as a progre,~ion of meth ods and theories that lead inextricably to a particular school of thought. Most linguists in the waning years of the twentieth century are comforted by the co incidence of the progression of linguistic knO\vledge with our contemporary theory of language. I hope to show in this essay the complex of issues that follow from a read ing of Tooke's The dfrersivns of Purley. Studies of the palit twenty years or ~o have concentrated on philosophical and political reputation and influences. 1 I present a brief biographical sketch. a summary of some necessary comments on Tooke the philosopher and Tooke the political figure . and a description and illustration of Tooke the theorist of language. Because there i~ relatively so lillle comprehensive and detailed work on the history of linguistics of any period, the methods and principles of language theory presented here cannot be exhaustively described and explained. -

Very Rough Draft

Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760-1776 Master‟s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Comparative History Mark Hulliung, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master‟s Degree by Jennifer M. Warburton May 2010 Copyright by Jennifer Warburton May 2010 ABSTRACT Friends and Colleagues: Intellectual Networking in England 1760- 1776 A Thesis Presented to the Comparative History Department Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Jennifer Warburton The study of English intellectualism during the latter half of the Eighteenth Century has been fairly limited. Either historians study individual figures, individual groups or single debates, primarily that following the French Revolution. My paper seeks to find the origins of this French Revolution debate through examining the interactions between individuals and the groups they belonged to in order to transcend the segmentation previous scholarship has imposed. At the center of this study are a series of individuals, most notably Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, Benjamin Franklin, Dr. John Canton, Rev. Theophilus Lindsey and John Jebb, whose friendships and interactions among such diverse disciplines as religion, science and politics characterized the collaborative yet segmented nature of English society, which contrasted so dramatically with the salon culture of their French counterparts. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ -

The Nature of the English Corresponding Societies 1792-95

‘A curious mixture of the old and the new’? The nature of the English Corresponding Societies 1792-95. by Robin John Chatterton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Arts by Research. Department of History, College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham, May 2019. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis relates to the British Corresponding Societies in the form they took between 1792 and 1795. It draws on government papers, trial transcripts, correspondence, public statements, memoirs and contemporary biography. The aim is to revisit the historiographical debate regarding the societies’ nature, held largely between 1963 and 2000, which focused on the influence on the societies of 1780s’ gentlemanly reformism which sought to retrieve lost, constitutional rights, and the democratic ideologies of Thomas Paine and the French Revolution which sought to introduce new natural rights. The thesis takes a wider perspective than earlier historiography by considering how the societies organised and campaigned, and the nature of their personal relationships with their political influences, as well as assessing the content of their writings. -

When Gunfire Was Regularly Heard on the Common

The London Forum of Amenity and Civic Societies NEWSLETTER December 2014 When gunfire was regularly heard on the Common Playing with Fire: The story of shooting on Wimbledon Common will open at the Norman Plastow Gallery on Saturday 17 January, writes LIZ COURTNEY. Running until Sunday, 12 April, it will be showing every Saturday and Sunday from 2.30–5pm and on Wednesdays from 11.30am–2.30pm. Duels were fought on the Common much earlier but in 1860, Earl Spencer, Lord of the Manor and a founder of the National Rifle Association, offered it for the NRA’s inaugural meeting. First opened by Queen Victoria, the event became Visitors endure the elements at one of the National Rifle popular in the social calendar. Association’s annual meets on Wimbledon Common. This Together with shooting watercolour is from the Museum’s collection. competitions, there were extra sporting events and musical Kirk triumphs entertainments. The illustration above right hints at the lively, as history less official, night life. The meetings grew in size awards finally and scope until, by the late 1870s, there were nearly 2500 revealed at entrants for the Queen’s Prize. The NRA flourished at Bookfest Wimbledon for nearly 30 years From the left, Society chairman Asif Malik, judge Richard Tait, before moving to Bisley in and Kirk Bannister, first winner of the Richard Milward Local 1890, the end of an era. History Prize. See Page 3 for details. INSIDE: News3 LocalHistoryGroup4/5 OralHistory6 Environment 7 Museum8 Planning Committee 8/11 Around and About 12 For the latest information, go to www.wimbledonsociety.org.uk, wimbledonmuseum.org.uk or the Facebook page. -

An Abstract from the Account of the Asylum, Or

A N ABSTRACT FROM THE ACCOUNT OF THE ASYLUM, O R, HOUSE OF REFUGE, SI.UATE IN THE PARISH OF LAMBETH, In the County of Surry ; INSTITUTED IN THE YEAR 17*58, FOR THE RECEPTION OF FRIENDLESS AND DESERTED ORPHAN GIRLS, The Settlement of whofe Parents cannot be found. PRINTED BY ©RDER OF THE GUARDIANS, 1799. A N ABSTRACT, Kc. r HOUGH the excellency of our laws, and the benevolence of the national chara&er feem to have made a provifion for almoft every fpecies of diftrefs to which the poor are liable, yet fituations will fometimes ari/'e, which the moft aftive and watch- ful charity could not at firft forefee. , and other indi- The children offoldiers, failors , their at a gent perfons bereft of parents , difiance to from relations, and too young afford the neceffary information refp effing fettlements, are often left de- and at when finite of proteffion fupport, an age they are incapable of earning fubfiftence , and contending with the dangers whichfurround them. Females of this defcription are, in a peculiar manner, objects of companion ; and have alfo a double claim to the care of the humane and virtu- ous, from being not only expofed to the miferies of want and idlenefs, but, as they grow up, to felicitations of the vicious, and to all the dread- ful confequences of early fedudlion. 1 his Charity owes Its ellablilhment to that vigilant and adkive Magiftrate, the late Sir John Fielding ; who had long obferved, that though the laws ofthis kingdom had provided a parijhfettle- merit every perfon, by for birth, parentage, appren- ticejhip, idc. -

The Unreformed Parliament 1714-1832

THE UNREFORMED PARLIAMENT 1714-1832 General 6806. Abbatista, Guido. "Parlamento, partiti e ideologie politiche nell'Inghilterra del settecento: temi della storiografia inglese da Namier a Plumb." Societa e Storia 9, no. 33 (Luglio-Settembre 1986): 619-42. ['Parliament, parties, and political ideologies in eighteenth-century England: themes in English historiography from Namier to Plumb'.] 6807. Adell, Rebecca. "The British metrological standardization debate, 1756-1824: the importance of parliamentary sources in its reassessment." Parliamentary History 22 (2003): 165-82. 6808. Allen, John. "Constitution of Parliament." Edinburgh Review 26 (Feb.-June 1816): 338-83. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index.] 6809. Allen, Mary Barbara. "The question of right: parliamentary sovereignty and the American colonies, 1736- 1774." Ph.D., University of Kentucky, 1981. 6810. Armitage, David. "Parliament and international law in the eighteenth century." In Parliaments, nations and identities in Britain and Ireland, 1660-1850, edited by Julian Hoppit: 169-86. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. 6811. Bagehot, Walter. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." National Review 10 (Jan.- April 1860): 215-55. 6812. ---. The history of the unreformed Parliament, and its lessons. An essay ... reprinted from the "National Review". London: Chapman & Hall, 1860. 43p. 6813. ---. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." In Essays on parliamentary reform: 107- 82. London: Kegan Paul, 1860. 6814. ---. "The history of the unreformed Parliament and its lessons." In The collected works of Walter Bagehot, edited by Norman St. John-Stevas. Vol. 6: 263-305. London: The Economist, 1974. 6815. Beatson, Robert. A chronological register of both Houses of the British Parliament, from the Union in 1708, to the third Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in 1807. -

Antidotes to Deism: a Reception History of Thomas Paine’S the Age of Reason, 1794-1809

ANTIDOTES TO DEISM: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF THOMAS PAINE’S THE AGE OF REASON, 1794-1809 by Patrick Wallace Hughes Bachelor of Arts, Denison University,1991 Master of Library Science, University of Pittsburgh, 1994 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Patrick Wallace Hughes It was defended on March 20, 2013 and approved by Van Beck Hall, Associate Professor, Department of History Alexander Orbach, Associate Professor Emeritus, Department of Religious Studies Marcus Rediker, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Adam Shear, Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Paula M. Kane, Associate Professor and John and Lucine O'Brien Marous Chair of Contemporary Catholic Studies, Department of Religious Studies ii Copyright © by Patrick Wallace Hughes 2013 iii ANTIDOTES TO DEISM: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF THOMAS PAINE’S THE AGE OF REASON, 1794-1809 Patrick Wallace Hughes, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 In the Anglo-American world of the late 1790s, Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason (published in two parts) was not well received, and his volumes of Deistic theology were characterized as extremely dangerous. Over seventy replies to The Age of Reason appeared in Britain and the United States. It was widely criticized in the periodical literature, and it garnered Paine the reputation as a champion of irreligion. -

Cata 188 Politics.Ppp

___________________________________________________________________________ Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 - 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 - 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London WC1B 3PA V.A.T. No. GB 524 0890 57 ___________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE CLXXXVIII SUMMER 2010 SOCIAL SCIENCE Part I: POLITICS & PHILOSOPHY Including sections on the British Empire, Ireland, The Oxford Movement, Political Economy. Catalogue: Ed Nassau Lake Production: Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Novels & Tales 1748-1926; Women II: Women Writers A-I; The Museum: Books for Presents; Books & Pamphlets of the 17th & 18th Centuries; 'Mischievous Literature': Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Social History of London: including Poverty & Public Health; The Jarndyce Gazette: Newspapers, 1660 - 1954; The Dickens Catalogue; Street Literature: I Broadsides, Slipsongs & Ballads; II Chapbooks & Tracts; Women I: Books for & about Women. Visit our searchable website: www.jarndyce.co.uk JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: George MacDonald; Women Writers J-Z; Social Sciences Part II: Economics & Social History. Street Literature: III Songsters, Lottery Puffs, Street Literature Works of Reference. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. -

Speech and Noise at the Westminster Elections Harriet Guest University of York

Speech and Noise at the Westminster Elections Harriet Guest University of York he westminster elections were a focus of national interest in the late eighteenth century. The behavior of the people was seen as a gauge of public opinion; and the conduct of the hustings, a measure of the national temper. Proximity to the houses of TParliament blurred the identities of the constituency and the nation, and the extensiveness of the franchise peculiar to Westminster gave it a strong claim to represent a more inclusive public than other districts. Westminster was a scot-and-lot borough, where in theory at least all men eligible to pay local rates—or, according to some, only those who had in fact paid the rates—over the preceding six months could vote. But the Westminster electorate was more capacious, more inclusive, even than other scot-and-lot constituencies. Marc Baer, in his recent study of the bor- ough, estimates that “three out of every four male householders could vote, including many ple- beians.”1 John Almon, political journalist and bookseller, commented in 1783 that “Westminster is the place, where the right of election comes nearest to the proportion of all persons having a right to vote. Every housekeeper there has a right to vote for members of parliament; and if there are two, or more partners, (even ten or a score) in the same house, they have all a right to vote for the same premises. This is pretty general.”2 This did not of course mean that those they voted for were representative, in some ideal democratic sense.