Securing the Nation Master2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DATES of TRIALS Until October 1775, and Again from December 1816

DATES OF TRIALS Until October 1775, and again from December 1816, the printed Proceedings provide both the start and the end dates of each sessions. Until the 1750s, both the Gentleman’s and (especially) the London Magazine scrupulously noted the end dates of sessions, dates of subsequent Recorder’s Reports, and days of execution. From December 1775 to October 1816, I have derived the end dates of each sessions from newspaper accounts of the trials. Trials at the Old Bailey usually began on a Wednesday. And, of course, no trials were held on Sundays. ***** NAMES & ALIASES I have silently corrected obvious misspellings in the Proceedings (as will be apparent to users who hyper-link through to the trial account at the OBPO), particularly where those misspellings are confirmed in supporting documents. I have also regularized spellings where there may be inconsistencies at different appearances points in the OBPO. In instances where I have made a more radical change in the convict’s name, I have provided a documentary reference to justify the more marked discrepancy between the name used here and that which appears in the Proceedings. ***** AGE The printed Proceedings almost invariably provide the age of each Old Bailey convict from December 1790 onwards. From 1791 onwards, the Home Office’s “Criminal Registers” for London and Middlesex (HO 26) do so as well. However, no volumes in this series exist for 1799 and 1800, and those for 1828-33 inclusive (HO 26/35-39) omit the ages of the convicts. I have not comprehensively compared the ages reported in HO 26 with those given in the Proceedings, and it is not impossible that there are discrepancies between the two. -

Romanticism and Linguistic Theory: William Hazlitt, Language and Literature P.Cm

Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Also by Marcus Tomalin: LINGUISTICS AND THE FORMAL SCIENCES Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory William Hazlitt, Language and Literature Marcus Tomalin Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert © Marcus Tomalin 2009 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publica- tion may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2009 by PALGRAVE macmILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin's Press LLC,175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

Scottsih Newspapers Have a Long Hisotry Fof Involvement With

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 051-127-E Division Number: V Professional Group: Newspapers RT Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 127 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries I.G.C. Hutchison University of Stirling Stirling, UK Abstract: Scotland is distinctive within the United Kingdom newspaper industry both because more people read papers and also because Scots overwhelmingly prefer to read home-produced organs. The London ‘national’ press titles have never managed to penetrate and dominate in Scotland to the preponderant extent that they have achieved in provincial England and Wales. This is true both of the market for daily and for Sunday papers. There is also a flourishing Scottish local weekly sector, with proportionately more titles than in England and a very healthy circulation total. Some of the reasons for this difference may be ascribed to the higher levels of education obtaining in Scotland. But the more influential factor is that Scotland has retained distinctive institutions, despite being part of Great Britain for almost exactly three hundred years. The state church, the education system and the law have not been assimilated to any significant amount with their counterparts south of the border. In the nineteenth century in particular, religious disputes in Scotland generated a huge amount of interest. Sport in Scotlaand, too, is emphatically not the same as in England, whether in terms of organisation or in relative popularity. Additionally, the menu of major political issues in Scotland often has been and is quite divergent from England – for instance, the land question and self-government. -

II. Hannah More: Concise Biography

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation HANNAH MORE: MORALIZING THE BRITISH NATION Verfasserin Mag. phil. Helga-Maria Kopecky angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreut von: o. Univ. Prof. Dr. Margarete Rubik 2 For Gerald ! 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to those who assisted me in various ways in this project: to my first supervisor, o. Professor Dr. Margarete Rubik, for guiding me patiently and with never ending encouragement and friendliness through a difficult matter with her expertise; to my second supervisor, ao. Professor Dr. Franz Wöhrer, for his valuable feedback; to the English and American Studies Library as well as the Inter-loan Department of the Library of the University of Vienna; the National Library of Australia; and last, but certainly not least, to my family. It was their much appreciated willingness to accept an absent wife, mother and grandmother over a long period, which ultimately made this work at all possible. Thank you so much! 4 Of all the principles that can operate upon the human mind, the most powerful is – Religion. John Bowles 5 Table of Contents page I. Introduction General remarks ……………………………………………………. 9 Research materials ………………………………………………... 12 Aims of this thesis ………………………………………………… 19 Arrangement of individual chapters ...…………………………... 22 II. Hannah More: Concise Biography Early Years in Bristol ……………………………………………….. 24 The London Experience and the Bluestockings ………………... 26 Return to Bristol and New Humanitarian Interests ................... 32 The Abolitionist .......................................................................... 34 Reforming the Higher Ranks ..................................................... 36 The Tribute to Patriotism ........................................................... 40 Teaching the Poor: Schools for the Mendips ............................ -

Enlightenment and Dissent No.29 Sept

ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISSENT No.29 CONTENTS Articles 1 Lesser British Jacobin and Anti-Jacobin Writers during the French Revolution H T Dickinson 42 Concepts of modesty and humility: the eighteenth-century British discourses William Stafford 79 The Invention of Female Biography Gina Luria Walker Reviews 137 Scott Mandelbrote and Michael Ledger-Lomas eds., Dissent and the Bible in Britain, c. 1650-1950 David Bebbington 140 W A Speck, A Political Biography of Thomas Paine H T Dickinson 143 H B Nisbet, Gottfried Ephraim Lessing: His Life, Works & Thought J C Lees 147 Lisa Curtis-Wendlandt, Paul Gibbard and Karen Green eds., Political Ideas of Enlightenment Women Emma Macleod 150 Jon Parkin and Timothy Stanton eds., Natural Law and Toleration in the Early Enlightenment Alan P F Sell 155 Alan P F Sell, The Theological Education of the Ministry: Soundings in the British Reformed and Dissenting Traditions Leonard Smith 158 David Sekers, A Lady of Cotton. Hannah Greg, Mistress of Quarry Bank Mill Ruth Watts Short Notice 161 William Godwin. An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice ed. with intro. Mark Philp Martin Fitzpatrick Documents 163 The Diary of Hannah Lightbody: errata and addenda David Sekers Lesser British Jacobin and Anti-Jacobin Writers during the French Revolution H T Dickinson In the late eighteenth century Britain possessed the freest, most wide-ranging and best circulating press in Europe. 1 A high proportion of the products of the press were concerned with domestic and foreign politics and with wars which directly involved Britain and affected her economy. Not surprisingly therefore the French Revolution and the French Revolutionary War, impacting as they did on British domestic politics, had a huge influence on what the British press produced in the years between 1789 and 1802. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Authority and utility: John Millar, James Mill and the politics of history c.1770- 1836 Westerman, I. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Westerman, I. (1999). Authority and utility: John Millar, James Mill and the politics of history c.1770-1836. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 The History of Authority CHAPTER FOUR 'THE COLD AND THANKLESS CLIMATE OF OPPOSITION' From May 1796 to August of the same year, Millar expressed his anxieties about the state of Britain in the light of the war with France in thirteen letters to the editor of the Scots Chronicle. The Scots Chronicle was an Edinburgh-based periodical that faced the harsh measures government took to dissuade the British populace from following the example set by the French. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Radical Returns in an Age of Revolutions: Maurice Margarot

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Radical Returns in an Age of Revolutions: Maurice Margarot, Thomas McFarlane and Andrew White Citation for published version: Pentland, G 2010, 'Radical Returns in an Age of Revolutions: Maurice Margarot, Thomas McFarlane and Andrew White' Etudes Ecossaises, vol. 13, pp. 92-101. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Etudes Ecossaises Publisher Rights Statement: © Pentland, G. (2010). Radical Returns in an Age of Revolutions: Maurice Margarot, Thomas McFarlane and Andrew White. Etudes Ecossaises, 13, 92-101. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 Études écossaises 13 (2010) Exil et Retour ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

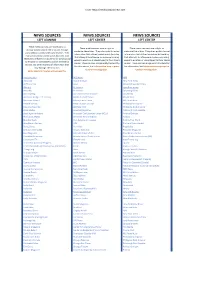

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to <I>Lyrical

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-15-2014 Revising for Genre: Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to Lyrical Tales Shelley AJ Jones University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, S. A.(2014). Revising for Genre: Mary Robinson's Poetry from Newspaper Verse to Lyrical Tales. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3008 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVISING FOR GENRE: MARY ROBINSON’S POETRY FROM NEWSPAPER VERSE TO LYRICAL TALES by Shelley AJ Jones Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2002 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2004 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Anthony Jarrells, Major Professor William Rivers, Committee Member Christy Friend, Committee Member Amy Lehman, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Shelley AJ Jones, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION For my boys. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project, like Robinson’s poetry, has benefited from the many versions it has taken. While many friends and colleagues, and my dissertation committee in its current composition, have been kind enough to offer guidance on my work over the years, I would like to acknowledge specifically Paula Feldman’s contribution as the former director of the dissertation committee. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise.