John Horne Tooke1s

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanticism and Linguistic Theory: William Hazlitt, Language and Literature P.Cm

Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Also by Marcus Tomalin: LINGUISTICS AND THE FORMAL SCIENCES Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert Romanticism and Linguistic Theory William Hazlitt, Language and Literature Marcus Tomalin Facebook : La culture ne s'hérite pas elle se conquiert © Marcus Tomalin 2009 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publica- tion may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2009 by PALGRAVE macmILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin's Press LLC,175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2007, 'The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair' Edinburgh Law Review, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 300-48. DOI: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Edinburgh Law Review Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (2007). The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair. Edinburgh Law Review, 11, 300-48doi: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 EdinLR Vol 11 pp 300-348 The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair John W Cairns* A. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

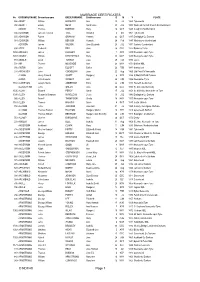

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Clare: Abstract and New Intro In

Citation for published version: Gittings, C & Walter, T 2010, Rest in peace? Burial on private land. in J Sidaway & A Maddrell (eds), Deathscapes: Spaces For Death Dying And Bereavement. Ashgate, Aldershot. Publication date: 2010 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Reproduced here by kind permission of Ashgate. University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Rest in Peace? Burial on Private Land Clare Gittings and Tony Walter Ever since the adoptation of Christianity in the early Middle Ages, it has been normal for Britain’s dead to be buried in churchyards or other Christian burial grounds (Daniell 1998; Jupp and Gitttings 1999). From the mid-nineteenth century, but with earlier examples in Scotland, cemeteries (i.e. formal burial grounds not attached to a church) have supplanted churchyards as the most common place of burial (Rugg 1997), augmented in the twentieth century by cremation (Jupp 2006). Private burial on your own land, rather than in churchyard or cemetery, has been and remains rare in Britain. It is, though, legal. -

Memoirs of the Life of Sir Samuel Romilly, Written by Himself, Ed. By

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 4c 102,1 MEMOIRS THE LIFE OF SIR SAMUEL ROMILLY, WRITTEN BY HIMSELF; WITH A SELECTION FROM HIS CORRESPONDENCE. EDITED BY HIS SONS. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. III. LONDON: JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. MDCCCXL. 1031. London : Printed by A. Spottiswoode, New- Street- Square. CONTENTS THE THIRD VOLUME. DIARY OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIFE OF SIR SAMUEL ROMILL Y — {continued). 1812. Slave trade ; Registry of slaves Bristol election; candidates; Mr. Protheroe. — Resolution of the Independent Club, and letter respecting it Mr. Protheroe; Hunt Address to the electors. — Mr. Rider's motion, police of the metro polis ; increase of crime. — Abuses in Ecclesiastical Courts ; Sir Wm. Scott. — Bristol election ; letter to Mr. Edge. — Reversion Bill. — Bill to repeal 39 Eliz. — Transportation to New South Wales. — The Regent's determination to re tain the ministers; his letter to the Duke of York. — Colonel M'Mahon's sinecure. — Delays in the Court of Chancery ; Michael Angelo Taylor. — Master in Chancery not fit mem ber of a committee to inquire into the delays of the court. — Expulsion of Walsh from the House of Commons. — Local Poor Bills; Stroud. — Military punishments; Brougham. — Bill to repeal 39 Eliz. ; Lord Ellenborough. — Abuses of charitable trusts ; Mr. Lockhart. — Visit to Bristol, reception, Speech second address to the electors. — Military punishments. — Cobbett's attack. — Committee on the delays in the Court of Chancery. — Disqualifying laws against Catholics. -

Re-Constructing Ideology, Part One: Animadversions of John Horne Tooke on the Origins of Affixes and Non-Designative Words

Re-constructing ideology, Part one: Animadversions of John Horne Tooke on the origins of affixes and non-designative words Fredric Dole~al J Introduction John Home Tooke occupies a unique place in the hi!)tory of Indo-European studies and lexicography - ohlivion: Only rarely in discussions of lndo Europcan linguistics and lexicography does one find a mention of the unre doubtablc, irascible. and scioli~tic champion of comparative and historical language study: but then. why ~hould a sciolist and purveyor of fanciful ety mologies he mentioned at all '? If we acknowledge the widely accepted propo sition that 'linguistics-as-we-know-it' began "1th Franz Bopp. then Home Tooke need not be considered at all. HoweH:r. this proposition can be main tained only by interpreting the history of linguistics as a progre,~ion of meth ods and theories that lead inextricably to a particular school of thought. Most linguists in the waning years of the twentieth century are comforted by the co incidence of the progression of linguistic knO\vledge with our contemporary theory of language. I hope to show in this essay the complex of issues that follow from a read ing of Tooke's The dfrersivns of Purley. Studies of the palit twenty years or ~o have concentrated on philosophical and political reputation and influences. 1 I present a brief biographical sketch. a summary of some necessary comments on Tooke the philosopher and Tooke the political figure . and a description and illustration of Tooke the theorist of language. Because there i~ relatively so lillle comprehensive and detailed work on the history of linguistics of any period, the methods and principles of language theory presented here cannot be exhaustively described and explained. -

John Wilkes: the Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty

John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty ARTHUR H. CASH John Wilkes THE SCANDALOUS FATHER OF CIVIL LIBERTY Yale University Press New Haven & London Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund and from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College. Copyright ∫ 2006 by Arthur H. Cash All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Sabon type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Arthur H. (Arthur Hill), 1922– John Wilkes : the scandalous father of civil liberty / Arthur H. Cash. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn-13: 978-0-300-10871-2 (alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-300-10871-0 (alk. paper) 1. Wilkes, John, 1727–1797. 2. Great Britain—Politics and government—1760– 1789. 3. Freedom of the press—Great Britain—History—18th century. 4. Civil rights—Great Britain—History—18th century. 5. Politicians—Great Britain— Biography. 6. Journalists—Great Britain—Biography. I. Title. da512.w6c37 2006 941.07%3%092—dc22 2005016633 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. -

A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3

Factsheet G3 House of Commons Information Office General Series A Brief Chronology of the August 2010 House of Commons Contents Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 2 15th and 16th centuries 3 Treason, revolution and the Bill of Rights: This factsheet has been archived so the content The 17th Century 4 The Act of Settlement to the Great Reform and web links may be out of date. Please visit Bill: 1700-1832 7 our About Parliament pages for current Developments to 1945 9 information. The post-war years: 11 The House of Commons in the 21st Century 13 Contact information 16 Feedback form 17 The following is a selective list of some of the important dates in the history of the development of the House of Commons. Entries marked with a “B” refer to the building only. This Factsheet is also available on the Internet from: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets August 2010 FS No.G3 Ed 3.3 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2010 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3 Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 1097-99 B Westminster Hall built (William Rufus). 1215 Magna Carta sealed by King John at Runnymede. 1254 Sheriffs of counties instructed to send Knights of the Shire to advise the King on finance. 1265 Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned a Parliament in the King’s name to meet at Westminster (20 January to 20 March); it is composed of Bishops, Abbots, Peers, Knights of the Shire and Town Burgesses. -

The Diaries of John Wilkes

Book review: The Diaries of John Wilkes John Wilkes (1725‐1797) is surely one of the most important and interesting political figures of the eighteenth century. A pioneering radical who championed parliamentary reform and numerous civil rights, he also had a famously colourful private life, which came to embody his public commitment to ‘liberty’ in all its forms. As such, it is remarkable that it has taken until now for his diaries to be published. As the editor of this fine new edition acknowledges, however, the diaries themselves may initially appear disappointing as a historical source. Robin Eagles even wonders out loud whether ‘diary’ may be a misnomer. ‘Dining book’ may be a more appropriate label, given that the daily entries almost exclusively record where he dined, and with whom (p.xxxii). These are not ‘journals’ in the same sense as those of his friend James Boswell. There is almost no narrative, little anecdote and nothing overt about the inner life. As Eagles argues in his introduction, the diaries ‘may say little of what he thought of it, but they do reveal much of the environment in which he lived’ (p.xii). To take a typical entry, that of 30 July 1786 reads: ‘dined at Richmond with Sir Joshua Reynolds, Miss Palmer, Mr W[illia]m Windham, Mr Cambridge, Mr Boswell, Mr Malone, Mr Courtn[e]nay, Lord Wentworth, Mr Metcalf, &c.’ (p.188). What immediately strikes the reader is the sheer extent of his acquaintance – the diaries read like a Who's Who of Georgian Britain – and the regularity with which Wilkes dines out, and in company.