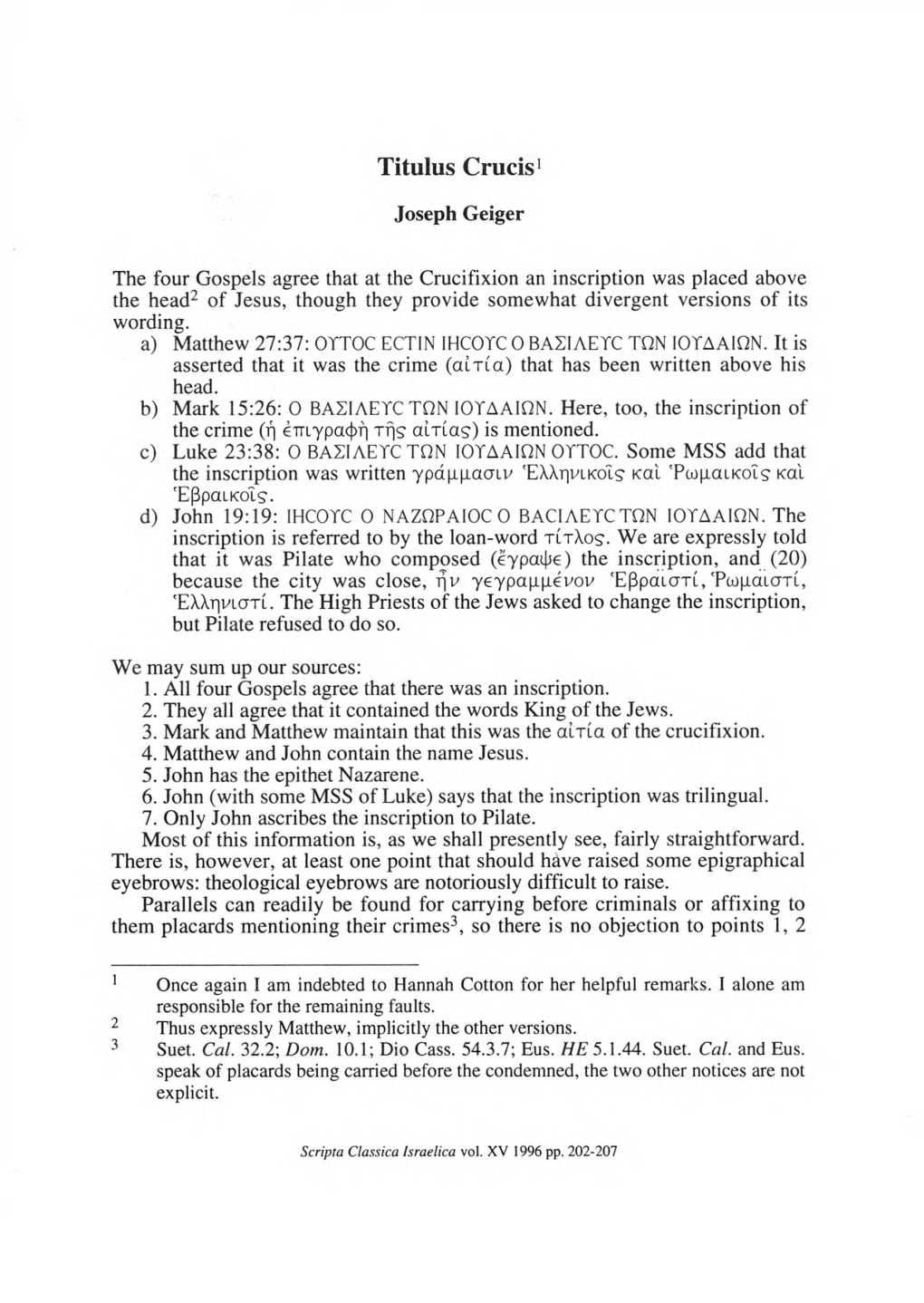

Titulus Crucis'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome: a Pilgrim’S Guide to the Eternal City James L

Rome: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Eternal City James L. Papandrea, Ph.D. Checklist of Things to See at the Sites Capitoline Museums Building 1 Pieces of the Colossal Statue of Constantine Statue of Mars Bronze She-wolf with Twins Romulus and Remus Bernini’s Head of Medusa Statue of the Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue Statue of Hercules Foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus In the Tunnel Grave Markers, Some with Christian Symbols Tabularium Balconies with View of the Forum Building 2 Hall of the Philosophers Hall of the Emperors National Museum @ Baths of Diocletian (Therme) Early Roman Empire Wall Paintings Roman Mosaic Floors Statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (main floor atrium) Ancient Coins and Jewelry (in the basement) Vatican Museums Christian Sarcophagi (Early Christian Room) Painting of the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Constantine Room) Painting of Pope Leo meeting Attila the Hun (Raphael Rooms) Raphael’s School of Athens (Raphael Rooms) The painting Fire in the Borgo, showing old St. Peter’s (Fire Room) Sistine Chapel San Clemente In the Current Church Seams in the schola cantorum Where it was Cut to Fit the Smaller Basilica The Bishop’s Chair is Made from the Tomb Marker of a Martyr Apse Mosaic with “Tree of Life” Cross In the Scavi Fourth Century Basilica with Ninth/Tenth Century Frescos Mithraeum Alleyway between Warehouse and Public Building/Roman House Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Find the Original Fourth Century Columns (look for the seams in the bases) Altar Tomb: St. Caesarius of Arles, Presider at the Council of Orange, 529 Titulus Crucis Brick, Found in 1492 In the St. -

Helena Augusta and the City of Rome Drijvers, Jan Willem

University of Groningen Helena Augusta and the City of Rome Drijvers, Jan Willem Published in: Monuments & Memory DOI: 10.1484/M.ACSHA-EB.4.2018013 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Drijvers, J. W. (2016). Helena Augusta and the City of Rome. In M. Verhoeven, L. Bosman, & H. van Asperen (Eds.), Monuments & Memory: Christian Cult Buildings and Constructions of the Past: Essays in Honour of Sible de Blaauw (pp. 149-155). Brepols Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.ACSHA- EB.4.2018013 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Alexander Nagel Some Discoveries of 1492

The Seventeenth Gerson Lecture held in memory of Horst Gerson (1907-1978) in the aula of the University of Groningen on the 14th of November 2013 Alexander Nagel Some discoveries of 1492: Eastern antiquities and Renaissance Europe Groningen The Gerson Lectures Foundation 2013 Some discoveries of 1492: Eastern antiquities and Renaissance Europe Before you is a painting by Andrea Mantegna in an unusual medium, distemper on linen, a technique he used for a few of his smaller devotional paintings (fig. 1). Mantegna mixed ground minerals with animal glue, the kind used to size or seal a canvas, and applied the colors to a piece of fine linen prepared with only a very light coat of gesso. Distemper remains water soluble after drying, which allows the painter greater flexibility in blending new paint into existing paint than is afforded by the egg tempera technique. In lesser hands, such opportunities can produce muddy results, but Mantegna used it to produce passages of extraordinarily fine modeling, for example in the flesh of the Virgin’s face and in the turbans of wound cloth worn by her and two of the Magi. Another advantage of the technique is that it produces luminous colors with a matte finish, making forms legible and brilliant, without glare, even in low light. This work’s surface was left exposed, dirtying it, and in an effort to heighten the colors early restorers applied varnish—a bad idea, since unlike oil and egg tempera distem- per absorbs varnish, leaving the paint stained and darkened.1 Try to imagine it in its original brilliant colors, subtly modeled throughout and enamel smooth, inviting us to 1 Andrea Mantegna approach close, like the Magi. -

University of Groningen Helena Augusta and the City of Rome

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Helena Augusta and the City of Rome Drijvers, Jan Willem Published in: Monuments & Memory DOI: 10.1484/M.ACSHA-EB.4.2018013 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Drijvers, J. W. (2016). Helena Augusta and the City of Rome. In M. Verhoeven, L. Bosman, & H. van Asperen (Eds.), Monuments & Memory: Christian Cult Buildings and Constructions of the Past: Essays in Honour of Sible de Blaauw (pp. 149-155). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.ACSHA- EB.4.2018013 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

The Practice of Piety and Virtual Pilgimage

THE PRACTICE OF PIETY AND VIRTUAL PILGIMAGE AT ST. KATHERINE’S CONVENT IN AUGSBURG _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by MISTY MULLIN Dr. Anne Rudloff Stanton, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2012 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE PRACTICE OF PIETY AND VIRTUAL PILGRIMAGE AT ST. KATHERINE’S CONVENT IN AUGSBURG presented by Misty Mullin, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Anne Rudloff Stanton Professor Norman Land Professor Rabia Gregory Mary L. Pixley, PhD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Anne Rudloff Stanton, my advisor, for suggesting that I read Pia Cuneo’s article “The Basilica Cycle of Saint Katherine’s Convent: Art and Female Community in Early-Renaissance Augsburg,” which led to the discovery of my thesis topic. I greatly appreciate all the encouragement and support she provided me throughout the thesis process and valued all her comments, which helped organize and clarify my writing. I could not have produced my thesis without her! I would also like to thank Dr. Norman Land for his dedication to good writing because it made me focus on the use of language and clarity in my own writing. I appreciate that he takes the time to actually look at art and I enjoyed hearing all of his humorous anecdotal stories. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Abbreviations and Symbols Founded in Biblical Manuscripts and Christians Icons

European Journal of Science and Theology, September 2010, Vol.6, No.3, 1-21 _______________________________________________________________________ ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS FOUNDED IN BIBLICAL MANUSCRIPTS AND CHRISTIANS ICONS Ilie Melniciuc Puică* University ‘Al. I. Cuza’, Faculty of Orthodox Theology, 9 Closca, 700065 Iasi, Romania (Received 1 March 2010, revised 4 June 2010) Abstract Word and image are highly correlated in Biblical codex and eastern icons. This connection is found among the scripta continua of the Biblical codex in which many abbreviations were used by scribes to unveil their text to foreign readers or to shorten their efforts. Developed in second or third century, this scribal habit of abbreviation became well established and generic form to refer to God, Jesus, Mary or the cross, until the statement of Christian icon. Later on such abbreviations became distinguished elements easily identifiable for both from the illiterate and the learned, which highlights the correlation of word and image. Keywords: abbreviation, codex, Sinaiticus, nomina sacra, icon 1. Introduction Abbreviations have been used as long as phonetic script existed. They were frequently used in early literacy, in which the spelling of a complete word was often avoided and in which initial letters were commonly being used to represent specific words. The reduction of words to single letters was continued in the Greek and Roman tradition. Properly speaking, contractions ought not to be confused with abbreviations or acronyms (including initialisms), with which they share some semantic and phonetic functions. Acronyms and initialisms are abbreviations that are formed by the beginning letters in a phrase or name. Contractions may perform the same function as abbreviations, but omit the middle of a word and are generally not terminated with a full point. -

A Holy Land for the Catholic Monarchy: Palestine in the Making of Modern Spain, 1469–1598

A Holy Land for the Catholic Monarchy: Palestine in the Making of Modern Spain, 1469–1598 A dissertation presented by Adam G Beaver to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2008 © 2008 Adam G Beaver Advisor: Prof. Steven E. Ozment Adam G Beaver A Holy Land for the Catholic Monarchy: Palestine in the Making of Modern Spain, 1469–1598 ABSTRACT Scholars have often commented on the ‘biblicization’ of the Spanish Monarchy under Philip II (r. 1556–1598). In contrast to the predominantly neo-Roman image projected by his father, Charles I/V (r. 1516/9–1556), Philip presented himself as an Old Testament monarch in the image of David or Solomon, complementing this image with a program of patronage, collecting, and scholarship meant to remake his kingdom into a literal ‘New Jerusalem.’ This dissertation explores how, encouraged by the scholarly ‘discovery’ of typological similarities and hidden connections between Spain and the Holy Land, sixteenth-century Spaniards stumbled upon both the form and content of a discourse of national identity previously lacking in Spanish history. The dissertation is divided into four chapters. In the first chapter, I examine three factors—the rise of humanist exegesis, a revitalized tradition of learned travel, and the close relationship between the crown and the Franciscan Order—that contributed to the development of a more historicized picture of the Holy Land in sixteenth-century Spanish sources. In Chapter Two, I focus on the humanist historian Ambrosio de Morales’ efforts to defend the authenticity of Near Eastern relics in Spanish collections. -

“May the Divine Will Always Be Blessed!” Newsletter No. 136 – September , A.D

The Pious Universal Union for the Children of the Divine Will Official Newsletter for “The Pious Universal Union for Children of the Divine Will –USA” Come Supreme Will, down to reign in Your Kingdom on earth and in our hearts! ROGATE! FIAT ! “May the Divine Will always be blessed!” Newsletter No. 136 – September , A.D. 2013 Our Lady of Sorrows By tradition, the Catholic Church dedicates each month of the year to a certain devotion. In September, it is Our Lady of Sorrows. The Memorial of Our Lady of Sorrows takes place on September 15, the day after the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross. We remember the suffering of Mary as she stood at the foot of the Cross and witnessed the torture and death of her Son. We also are reminded of Simeon's words to Mary (Luke 2:34-35) at the Presentation of the Lord—that a sword would pierce her soul. Some or all of the following prayers can be incorporated into our daily prayers during the Month of Our Lady of Sorrows. 1 September 8, A.D. 2013 - Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary Day Ten The Queen of Heaven in the Kingdom of the Divine Will Lesson of the Newborn Queen: Child of my Heart, my birth was prodigious; no other birth can be said to be similar to mine. I enclosed in Myself the heaven, the Sun of the Divine Will, and also the earth of my humanity – a blessed and holy earth, which enclosed the most beautiful flowerings. And even though I was just newly born, I enclosed the prodigy of the greatest prodigies: the Divine Will reigning in Me, which enclosed within Me a heaven more beautiful, a Sun more refulgent than those of Creation, of which I was also Queen, as well as a sea of graces without boundaries, which constantly murmured: "Love, love to my Creator…" My birth was the true dawn that puts to flight the night of the human will; and as I kept growing, I formed the daybreak and called for the brightest daylight, to make the Sun of the Eternal Word rise over the earth. -

The True Cross: Chaucer, Calvin, and the Relic Mongers

SI New Nov Dec pages_SI new design masters 9/24/10 2:28 PM Page 18 [ INVESTIGATIVE FILES J OE NI CK E L L Joe Nickell, PhD, is CSI’s senior research fellow and author of such books as Inquest on the Shroud of Turin, Relics of the Christ, and Looking for a Miracle. The True Cross: Chaucer, Calvin, and the Relic Mongers lthough there is little justifica- which according to legend was discov- That ‘Greed is at the root of all evil.’” tion in either the Old or the ered in the fourth century by St. He- But the Pardoner is merely a hypocrite. A New Testament to support what lena. First, he displays his letters of approval would become a cult of relics in early Chaucer’s ‘Pardoner’s Tale’ signed by the Pope. Then he brings out Christianity, such a practice did de- his reliquaries, with bits of cloth and The Canterbury Tales (ca. 1386 –1400) is velop. The earliest veneration of Chris- other alleged relics, including the CE Geoffrey Chaucer’s fictional classic tian relics can be traced to about 156 shoulder bone of a sheep, and declares: when Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna, compilation of stories told by traveling was martyred and his burned remains pilgrims, including the host of the “If when this bone be washed in any well, were gathered for veneration. In time, Tabard Inn in Southwark, England, If cow, or calf, or sheep, or ox the distribution and veneration of pack- from whence said Pilgrims set out, should swell ets of dust and tiny fragments of bone wending their way to Canterbury From eaten worm, or by a snake’s or cloth, and the like—associated with Cathedral. -

Your Italian Pilgrimage Unpacked

Beautiful Catholicism Your Italian pilgrimage unpacked Index Scripture to consider………………...……………………………………… Page 3 Hotel Information…………………………………………...………………. Page 4 Day 2 (Arrive in Italy and bus from Rome to Florence)……………………... Page 5 Day 3 (Florence)……………………………………………………………… Page 6 Academia & Uffizzi………………………………………………………. Page 7 San Marco Convent Museum…………………………………………….. Page 8 Florence Cathedral………………………………………………..………. Page 9 San Miniato al Monte (St. Minias on the Mountain) …………………….. Page 10 Day 4 (Siena)………………………………………………………..………... Page 11 Saint Catherine Biography……………………………………………….. Page 12 Basilica Cateriniana di san Domenico………………………..…………. Page 13 Day 5 & 6 (Assisi)……………………………………………………………. Page 14 Santa Maria Degli Angeli, Assisi………………………………………... Page 15—16 St. Francis’s hermitage…………………………………………………... Page 17 Basilica of St. Francis………………………………………………..…... Page 18 Umbrian hill town of Assisi and Santa Chiara church………………….. Page 19 Day 7 (Orvieto & Rome)……………………………………….…………….. Page 20 Cathedral of Orvieto & Eucharistic Miracle……………………………... Page 21 St. Peters Basilica (Rome)……………………………………………….. Page 22 Borgo Pio Neighborhood; Day 7 dinner…………………………………. Page 23 Day 8 (Papal Audience, Major Basilica’s, Sacred Relics)…………………… Page 24 Papal Audience (St. Peters Square)……………………………………... Page 25 St. John Latern The worlds cathedral…………………………………… Page 26 Santa Maria Maggiore (Mary Major)…………………………………… Page 27 Holy Stairs, Pillar of Scourging, Relic of the true cross: Basilica's of Scala Santa, St. Praxedes & Santa Croce …………………. Page 28 Day 9 (Mass at tomb of St. Peter & Vatican Museum)……………………… Page 29 Mass at Catacombs of St. Peter & Sistine Chapel tour………………….. Page 30 Vatican Museum………………………………………………………… Page 31-32 Day 10 (St. Paul Outside Walls, Basilica’s, Peter in Chains, Pantheon)…………... Page 33 Basilica of Saint Paul outside the walls…………………………………. Page 34 Santa Maria Sopra Minerva and San Pietro in Vincoli (Peter in Chains)….. Page 35-36 The Panthon…………………………………………………………….. -

Fourth Sunday in Lent (Laetare Sunday), 11Th March 2018

Fourth Sunday in Lent (Laetare Sunday), 11th March 2018 There are a number of Sundays throughout the year which are named after the first word of the Introit, like today of course: Laetare Sunday. The Introit consists of an antiphon and then the beginning of a psalm (originally a whole psalm); the antiphon as a general rule being a verse taken from the psalm itself and repeated again at the end. Today‟s antiphon is therefore one of the exceptions; since it comes not from the psalm, one hundred and twenty one in this case, “Laetatus sum (I rejoiced)”, but rather from the last chapter, chapter sixty-six (v. 10), of the prophet Isaiah. The psalm, Laetatus sum, is absolutely ideal for an Introit, which was intended as the music for the procession to the altar: “I rejoiced at the things that were said to me: We shall go into the house of the Lord” (Ps 121:1), and so on. If I were to use a different translation, you probably would recall a certain historic occasion, together with a particular piece of music: “I was glad when they said unto me: We will go into the house of the Lord”. Westminster Abbey, 1953, might come to mind. Although the antiphon beginning with “Laetare (Rejoice)” comes from Isaiah rather than from the Psalm, Laetatus sum (“I rejoiced”, or “I was glad”, if you prefer), it is quite obvious why they have been placed together. This theme of rejoicing is also present in today‟s Epistle, from St Paul to the Galatians: “Laetare, sterilis (Rejoice, thou barren)” (4:27). -

Shroud Spectrum International No. 16 Part 3

2 Fig. 1: The fragment of the Title of the Cross, behind glass in a silver reliquary. The wood, very badly deteriorated, is now tobacco-color. Almost no flecks of white or red paint can be detected. 3 THE TITLE OF THE CROSS* JOSEPH UTEN Like the Holy Shroud, the Title of the Cross is a witness to the veracity of the evangelical texts concerning the last hour of the mortal life of Jesus, and like the Shroud it deserves to be known. In Roman times, when a condemned man was led to his punishment, a placard indicating the motive of his condemnation was carried in front of him or he himself carried it suspended from his neck.1 Pilate complied with this custom when he condemned Jesus and it was he who composed the text of the inscription. He wanted it to be written in Hebrew, language of the people of the country; in Greek, language of the Jews of the dispersion and of foreigners; and in Latin, the official language of the government. The Title was fixed at the top of the Cross and could be read by the great numbers of passersby (Jn 19:19,20). All four Evangelists mention the Title but not all of them quote it exactly. The quotation most familiar to us must undoubtedly be the complete text, since it indicates not only the reason for condemnation but also the name of the condemned and his origin: Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews. From all the accusations brought to his tribunal, Pilate picked the one which had overcome his hesitations; the title of "king" ascribed to Jesus, and which the Jews themselves pointed out to be in opposition to the rights of Caesar.