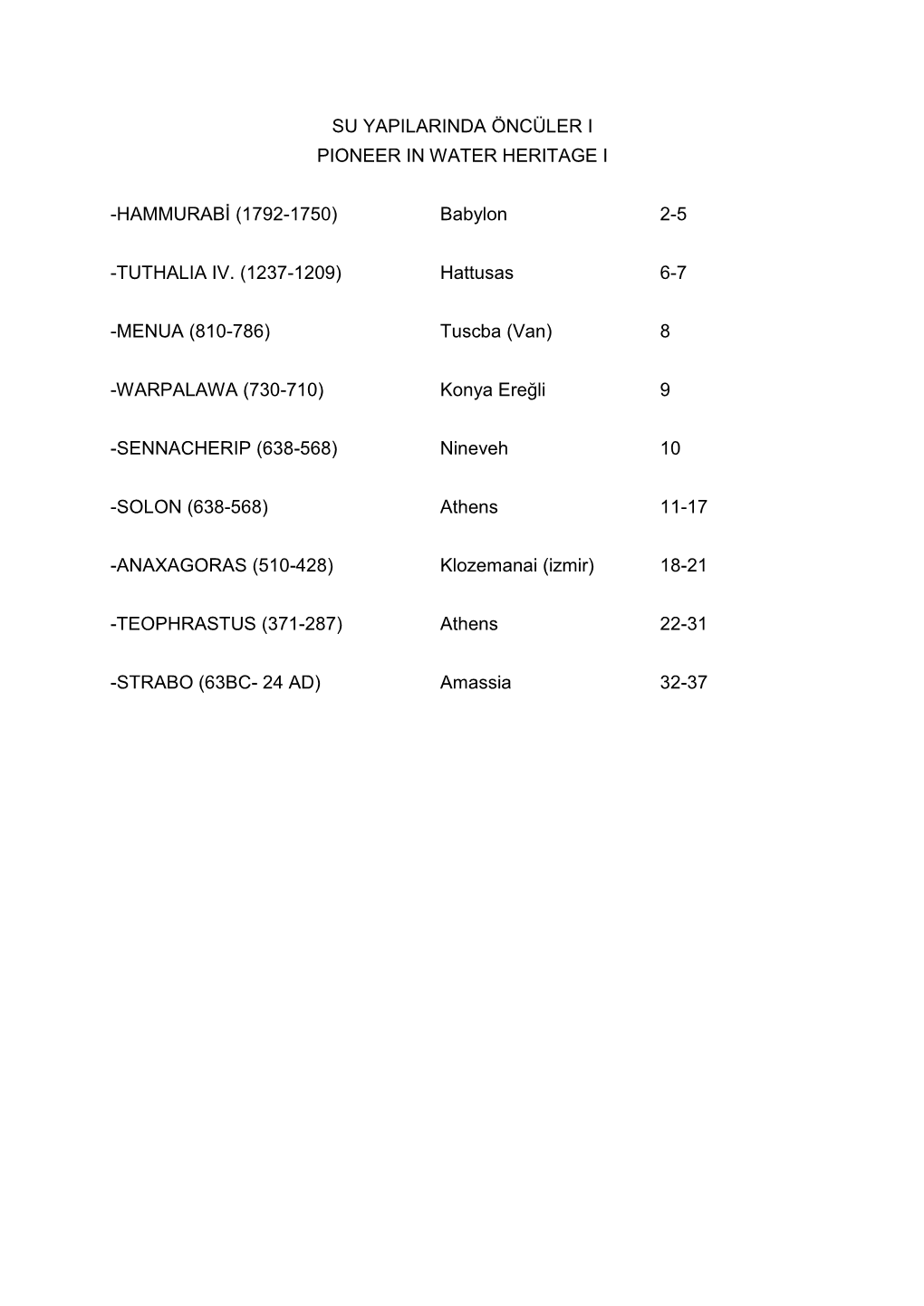

HAMMURABİ (1792-1750) Babylon 2-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hittite Rock Reliefs in Southeastern Anatolia As a Religious Manifestation of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFESTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES A Master’s Thesis by HANDE KÖPÜRLÜOĞLU Department of Archaeology İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2016 HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFESTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by Hande KÖPÜRLÜOĞLU In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY September 2016 ABSTRACT HITTITE ROCK RELIEFS IN SOUTHEASTERN ANATOLIA AS A RELIGIOUS MANIFASTATION OF THE LATE BRONZE AND IRON AGES Köpürlüoğlu, Hande M.A., Department of Archaeology Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates September 2016 The LBA rock reliefs are the works of the last three or four generations of the Hittite Empire. The first appearance of the Hittite rock relief is dated to the reign of Muwatalli II who not only sets up an image on a living rock but also shows his own image on his seals with his tutelary deity, the Storm-god. The ex-urban settings of the LBA rock reliefs and the sacred nature of the religion make the work on this subject harder because it also requires philosophical and theological evaluations. The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate the reasons for executing rock reliefs, understanding the depicted scenes, revealing the subject of the depicted figures, and to interpret the purposes of the rock reliefs in LBA and IA. Furthermore, the meaning behind the visualized religious statements will be investigated. -

Cambridge Histories Online

Cambridge Histories Online http://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/histories/ The Cambridge World Prehistory Edited by Colin Renfrew, Paul Bahn Book DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139017831 Online ISBN: 9781139017831 Hardback ISBN: 9780521119931 Chapter 3.10 - Anatolia from 2000 to 550 bce pp. 1545-1570 Chapter DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139017831.095 Cambridge University Press 3.10 ANATOLIA FROM 2000 TO 550 BCE ASLI ÖZYAR millennium, develops steadily from an initial social hierarchy, The Middle Bronze as is manifest in the cemeteries and settlement patterns of Age (2000–1650 BCE) the 3rd millennium BCE, towards increased political complex- ity. Almost all sites of the 2nd millennium BCE developed on Introduction already existing 3rd-millennium precursors. Settlement con- tinuity with marked vertical stratification is characteristic for the inland Anatolian landscape, leading to high-mound for- Traditionally, the term Middle Bronze Age (MBA) is applied to mations especially due to the use of mud brick as the preferred the rise and fall of Anatolian city-states during the first three building material. Settlement continuity may be explained in centuries of the 2nd millennium BCE, designating a period last- terms of access to water sources, agricultural potential and/or ing one-fifth of the timespan allotted to the early part of the hereditary rights to land as property mostly hindering horizon- Bronze Age. This is an indication of the speed of developments tal stratigraphy. An additional or alternative explanation can be that led to changes in social organisation when compared to the continuity of cult buildings, envisaged as the home of dei- earlier millennia. -

Notes Brèves

ISSN 0989-5671 2019 N° 1 (mars) NOTES BRÈVES 1) Some considerations on the geographical lists from the Uruk III period* — This note is a compilation of observations made from a comparison of the Proto-Euphratic (PE) list “Cities” (ATU 3) with the geographical lists “Geography” published in ATU 3 (henceforth GL, numbers 1–8 and X) and the only other known GL, namely MS 3173 (:= GL 9).1) In the first instance only the list “Cities” itself (because of the well-known place names) and GL 8 (URU in the colophon) can without doubt be seen as GLs. The list “Cities” makes it clear that there was originally no determinative for GNs: Determinatives are added to (almost) all the entries in a list.2) AB und É could be termed as “2nd order determinatives” as they are part of several GNs but are not used throughout (see NABU 2013/55, note 13).3) GL 8, a “non-canonical” GL, shows that a determinative for GNs (especially not KI) was never introduced in the PE writing system (KI occurs in GL 8 at the beginning and at the end of toponyms, so it is a sign like any other).4) In the other GLs only the GNs GI UNUG, ILDUM, NÍ, NUN A and UB, which are known from Cities and GL 8, can with certainty be found. To ASAR und NUN (?) the determinative KI is added. Each of the lists contains only a few of these GNs;5) the lists are linked to each other by further entries.6) The appearance of a GN in a list does not necessarily mean that it is a GN list: Compare UNUG in Cities and in Lú A; the GN ŠENNUR (GL 1, 2, 3, 9) is also listed in “Tribute” and is probably not a GN there. -

The Phrygian God Bas

The Phrygian god Bas BARTOMEU OBRADOR-CURSACH, University of Barcelona* Among the gods identified in the Phrygian corpus, Bas the third most referenced god after Ti- (the Phrygian stands out because of the lack of a Greek counterpart. Zeus, documented almost exclusively in NPhr. curses) Indeed, Matar equates, more or less, to Κυβέλη, Ti- to and Matar (the Mother-Goddess, exclusively in OPhr. Ζεύς1, Artimitos (B-05) 2 to Ἄρτεμις,3 Διουνσιν (88) monuments). The high number of references allow to Διόνυσος, and Μας (48) to Μήν.4 Yet Bas remains for the analysis of his purpose and the identification without a clear equivalent and seems to only appear of the origin of his name in the light of our increas- in Phrygian texts. He occurs almost eight times in ing knowledge of Phrygian and the general Anatolian different contexts of both the Old Phrygian (OPhr.) framework. and New Phrygian (NPhr.) corpora. This makes Bas The oldest occurrence of this theonym is docu- mented in the Luwian city of Tuwanuwa in Cappa- Τύανα * This paper was funded by the research project Los dialectos docia (called in Greek, and currently called lúvicos del grupo anatolio en su contexto lingüístico, geográfico e Kemerhisar). The name of Bas can be read on a frag- histórico (Ref. FFI2015–68467–C2–1–P) granted by the Spanish ment of a severely damaged stele discovered in 1908 Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness. (T-02b). Although most of the monument is lost, its 1 A. Lubotsky, “The Phrygian Zeus and the problem of the ‘Laut- verschiebung’,” Historische Sprachforschung 117 (2004): 230–31. -

Turgut Yiğit*

Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi 40, 3-4 (2000), 177-189 Tabal Turgut Yiğit* Özet Anadolu'da ilk kez geniş çaplı siyasal birliği M.Ö. II. binyılın ilk yarısında Hititler gerçekleştirmişlerdir. Onların Kızılırmak kavsinin içi merkez olmak üzere kurdukları devlet, buradan daha geniş sınırlara yayılmış, M.Ö. XII. yüzyıl başlarında ise son bulmuştur. Geç Hitit Devletleri, yıkılan Büyük Hitit Devleti'nin siyasal ve kültürel mirasçılarıdırlar. Bunların içinde en batıda yer alanı ise Tabal'dir. Tabal'in sınırları, kuzeyde Kızılırmak'tan güneyde Aladağlar ve Bolkar Dağları'na; batıda Tuz Gölü'nden doğuda Gürün'e dek uzanır. Bu Geç Hitit devletinin tarihini biz, diğerlerininkini olduğu gibi daha çok Asur kaynaklarına dayalı olarak inceleyebiliyoruz. Ancak bu kaynaklar Tabal'in tarihini bir bütün olarak vermekten uzaktır. Zira Asur ve Tabal'in ilişkileri ile sınırlı kayıtlar söz konusudur. Tabal'in yayıldığı sınırlar içerisinde ele geçen hiyeroglif yazıtlar da bu ülkenin tarihi ve kültürüne dair yeterli bilgiler vermekten uzaktır. Asur kaynakları ile yerli hiyeroglif yazıtlar arasında yer ve şahıs isimleri dolayısıyla paralellik kurulmakta ve bunlar bir arada kronolojik sıra ile değerlendirilebilmektedir. Orta Anadolu'dan Malatya ve Suriye'ye uzanan bir alanda yayılmış olduklarını gördüğümüz Geç Hitit Devletleri, Anadolu'da ilk kez geniş kapsamlı siyasal birliği sağlayan ve bu topraklarda yüzyıllarca egemen olduktan sonra M.Ö. XII. yüzyıl başlarında yıkılan Hitit Devleti'nin kültürel ve siyasal açıdan mirasçısıdırlar. Bunların içinde en batıda olanı Tabal'dir. Tabal ile, daha baştan kabaca söylersek, Kayseri, Nevşehir ve Niğde illerini kapsayan bölge kastedilmektedir. Tabal'in tarihi, diğer Geç Hitit Devletleri'nde olduğu gibi, daha çok Asur kaynaklarına dayalı olarak incelenebilmektedir. -

Ivriz Cultural Landscape

Ivriz Cultural Landscape Turkey Date of Submission: 15/04/2017 Criteria: (ii)(iii)(iv) Category: Cultural Submitted by: Permanent Delegation of Turkey to UNESCO State, Province or Region: Province of Konya, District of Halkapınar, Village of Ivriz Coordinates: E34 09 53.22 N37 23 46.79 Ref.: 6244 Description The Ivriz Cultural Landscape includes in situ two large Neo-Hittite rock reliefs, and a small Neo-Hittite altar, as well as a monastery dating to the Middle Byzantine Period, two caves and natural features such as springs. The site was used as a frontier marker, and as a religious and cultic area over a long span of time from the Late Bronze Age (1650-1200 BC), through Iron Age (1200-650 BC) and down to the Middle - Late Byzantine period (843-1543 AD). Mentioned as DKASKAL.KUR in the Late Bronze Age by the Hittites, it was an important frontier marker and later in the Iron Age it became an important water cult sanctuary and this continued into the Byzantine Period where the site was used again as a religious setting for an important monastery. Ivriz village is located 170 km south-east of the city of Konya, 2.9 km south of the provincial town of Halkapınar. The village is settled on the slopes of the Mount Bolkar, which is the middle part of the Taurus Mountain range. The village is also placed in the south-east of the Konya plain, and right next to the wetlands and the streams created by the Ivriz Creek. Ivriz village represents all the elements of an integrated landscape, including springs, nature and an active rural life style which is important for continuing socio-cultural heritage. -

Post Hittite Historiography in Asia Minor

Post Hittite Historiography in Asia Minor Ἀ. Uchitel I am fully aware that the use of the word “historiography” is controversial when applied to non-Greek historical writing. Nevertheless, bearing in mind the basic difference between the Greek concept of historia, as ra tional historical research, and other traditions, I believe that it is still possible to use the term “historiography” for at least such exclusively historical Near Eastern genres as the Babylonian Chronicles, and the Hit tite and Asyrian royal annals.1 After all, these compositions were written for no other reason than the recording of past events, without any visible practical aim. Using the word in this broad sense, Hittite historiography is well known. In fact, the Hittite royal annals can be regarded as the earliest example of this genre anywhere in the world. Since there is an excellent survey of the Hittite historiography by Hoffner,21 do not need to elaborate. Two historical genres will be mentioned in the course of our discussion: royal annals and royal autobiographies. I would like to recall that what we call “royal annals”, the Hittites themselves called pesnatar — “manly deeds”. These were accounts of military campaigns, year by year, written in the first person, in the name of the king himself. In this respect they resemble rather the Roman genre of res gestae than that of annales. Unlike the Assyrian annals, which developed from the building inscriptions and maintained this connection in the form of the so-called Baubericht — an account of the building activity of the king, 1 The problems of Ancient Near Eastern historiography are discussed in: Histories and Historians of the Ancient Near East, Orientalia 49 (1980), esp. -

Textiles, Trade and Theories Textiles Have Textiles Always Been Among the Most Popular Goods of Mankind

Textiles. Trade and Theories, from the Ancient Near East to the Mediterranean. Nosch, Marie Louise Bech; Dross-Krüpe , Kerstin Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Nosch, M. L. B., & Dross-Krüpe , K. (Eds.) (2016). Textiles. Trade and Theories, from the Ancient Near East to the Mediterranean. Ugarit-Verlag, Münster. Karum – Emporion – Forum. Beiträge zur Wirtschafts-, Rechts- und Sozialgeschichte des östlichen Mittelmeerraums und Altvorderasiens Vol. 2 Download date: 30. sep.. 2021 KEF 2 Beiträge zur Wirtschafts-, Rechts- und Sozialgeschichte Kārum – Emporion – Forum Textiles, Trade and Theories Textiles, Trade and Theories Trade Textiles, Textiles have always been among the most popular goods From the Ancient Near East of mankind. Considering their significance in the ancient Mediterranean and the ancient Near East alike, as well as to the Mediterranean their value as key economic assets, textiles hold significant potential for the understanding of the ancient economy. Making them the subject of more detailed economic analyses in their own right is a central objective of the present volume. Because it is not possible to analyze distributional Edited by Kerstin Droß-Krüpe patterns or the channels of distribution for ancient textiles exclusively on the basis of either written sources and Marie-Louise Nosch or archaeological findings, this volume brings together different source material, disciplines, and methodological approaches, including modern Economics, to analyze the 2 textiles that were traded, trade-routes, markets for buying ⋼ and selling, and the formation and operation of institutions des östlichen Mittelmeerraums und Altvorderasiens that ensured the smooth functioning of processes of textile exchange. -

Photogrammetric Survey and 3D Modeling of Ivriz Rock Relief in Late Hittite Era

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 13, No 2, pp. 147-157 Copyright © 2013 MAA Printed in Greece. All rights reserved. PHOTOGRAMMETRIC SURVEY AND 3D MODELING OF IVRIZ ROCK RELIEF IN LATE HITTITE ERA İsmail Şanlıoğlua, Mustafa Zeybeka, Güngör Karauğuzb a Department of Geomatics Engineering, University of Selcuk,Turkey b Education Faculty, University of Necmettin Erbakan, Turkey Received: 15/12/2012 Accepted: 17/01/2013 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT In this study, the photogrammetric measurement technique was used to document the Ivriz re- lief, which is located under the Kocaburun Rock on Mount Aydos in the village of Ivriz (Ay- dınkent), Konya-Eregli. This relief has been standing since B.C. 720 but suffers from man and envi- ronmental agents. It has been standing high from ground on rock façade. Therefore a 3D (three- dimensional) model of the monument was obtained as a result of the work conducted for protec- tion. Conservation has been done by close-range photogrammetry technique. Using close-range photogrammetry, in which only some brief field work was done with a majority of the other work being conducted in an office, documentation can be efficiently performed using free equipment and software as well as scaled archives to produce three-dimensional models of historical and cultural heritages in a digital environment. KEYWORDS: Ivriz, Close-range Photogrammetry, Cultural Heritage 148 İ. ŞANLIOĞLU et al 1. INTRODUCTION range photogrammetry is a very effective and Many of our historical and cultural heritages useful method for documenting these heritages. suffer serious damage caused by a lack of care This paper is an application of digital close- or natural disasters, and consequently, they dis- range photogrammetry to Ivriz relief for the appear. -

Of God(S), Trees, Kings, and Scholars

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

A Happy Son of the King of Assyria: Warikas and the Çineköy Bilingual (Cilicia)

A HAPPY SON OF THE KING OF ASSYRIA: WARIKAS AND THE ÇINEKÖY BILINGUAL (CILICIA) Giovanni B. lanfranchi Over the course of many years, and in many skilled, stimulating and sometimes very provocative studies, Simo Parpola has examined various aspects of the conceptual constellation structuring and governing the ideology of Neo-Assyrian kingship. His basic assumption was and is the concept that the royal ideology was the most crucial element not only in supporting the tremendous effort of Assyrian military and administrative expansion, but also, and especially, in consolidating the expansion through the transmission of Assyrian culture to both the conquered and the still independent populations. The conscious aim of acculturation was to encourage and to develop a pro-Assyrian attitude in the peripheral, non-Assyrian social elites, a long process which at the end produced a global “Assyrianization” of the whole Near East. I am extremely happy, and I thank the editors very much for inviting me, to dedicate to him a study on this subject, in acknowledgment of his scholarly, social and human merits, and as a poor witness of my esteem and of my personal friendship – both unchanged since we met at the Cetona meeting 28 years ago. From a methodological point of view, the development of a pro-Assyrian attitude among members of the elites of the peripheral states should be taken a priori as a natural and unavoidable phenomenon, to be compared to many other similar examples in different historical and cultural milieus.1 In the case of Assyria, however, this basic reality is either opposed or still very doubtfully accepted in a large part of scholarly research. -

Karkamiš in the First Millennium Bc

KARKAMIŠ IN THE FIRST MILLENNIUM B.C.: SCULPTURE AND PROPAGANDA A Master’s Thesis by KADRİYE GÜNAYDIN Department of Archaeology and History of Art Bilkent University Ankara May 2004 To my parents KARKAMIŠ IN THE FIRST MILLENNIUM B.C.: SCULPTURE AND PROPAGANDA The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by KADRİYE GÜNAYDIN In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA May 2004 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. --------------------------------- Assoc. Prof. İlknur Özgen Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Charles Gates Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. --------------------------------- Assoc. Prof. Aslı Özyar Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------------- Prof. Kürşat Aydoğan Director ABSTRACT KARKAMIŠ IN THE FIRST MILLENNIUM B.C.: Günaydın, Kadriye M.A., Department of Archaeology and History of Art Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. İlknur Özgen May 2004 This thesis examines how the monumental art of Karkamiš, which consists of architectural reliefs and free-standing colossal statues, was used by its rulers for their propaganda advantages.