School Partnerships and Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

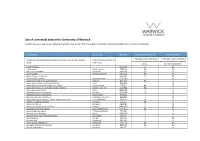

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick Please Use

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick Please use the table below to check whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for a contextual offer. For more information about our contextual offer please visit our website or contact the Undergraduate Admissions Team. School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school which meets the 'Y' indicates a school which meets the Free School Meal criteria. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. school performance citeria. 'N/A' indicates a school for which the data is not available. 6th Form at Swakeleys UB10 0EJ N Y Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School ME2 3SP N Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST2 8LG Y Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton TS19 8BU Y Y Abbey School, Faversham ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent DE15 0JL Y Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool L25 6EE Y Y Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Y N Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge UB10 0EX Y N School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals Abbs Cross School and Arts College RM12 4YQ Y N Abbs Cross School, Hornchurch RM12 4YB Y N Abingdon And Witney College OX14 1GG Y NA Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Y Y Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Y Y Abraham Moss High School, Manchester M8 5UF Y Y Academy 360 SR4 9BA Y Y Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Y Y Acklam Grange -

15 Small Schools. INSTITUTION Human Scale Education, Bath (England)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 974 RC 023 307 AUTHOR Spencer, Rosalyn TITLE 15 Small Schools. INSTITUTION Human Scale Education, Bath (England). PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 50p. AVAILABLE FROM Human Scale Education, 96 Carlingcott, Nr Bath, BA2 8AW, UK (3.50 British pounds, plus 1 pound postage). E-mail: [email protected]. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Environment; Educational Philosophy; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Environmental Education; Experiential Learning; Foreign Countries; *Nontraditional Education; *Parent Participation; *Participative Decision Making; *School Community RelationshiP; *Small Schools IDENTIFIERS Place Based Education; Sense of Community; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This report details findings from visits to 15 small schools associated with Human Scale Education. These schools are all different, reflecting the priorities of their founders. But there are features common to all of them--parental involvement, democratic processes, environmentally sustainable values, spiritual values, links with the local community, an emphasis in co-operation rather than competition, and mixed age learning. The characteristic that links them all is smallness, and it is their small size that makes possible the close relationships fundamental to good learning. By good learning, the schools mean learning in a holistic sense, encompassing the development of the creative, emotional, physical, moral, and intellectual potential of each person. Contact information, grade levels and number of students taught, and a brief history are given for each school. Educational philosophy, school-community relationships, educational practices, and grading systems are described, as well as the extent to which the national curriculum and SATs are used. Environmental education and activities, service learning, experiential activities, and exposure to the world of work are extensive. -

AERO 11 Copy

TALK AT NY OPEN CENTER Three days after getting back from the trip to the Alternative Education Conference in Boulder, I was scheduled to speak at the New York Open Center, in New York City. This was set up at the suggestion of Center Director Ralph White, who had heard about my teacher education conferences in Russia, and wanted to share information about a new center they are setting up there. Although there were not many pre-registered, I was surprised to find an overflow audience at the Center, with great interest in educational alternatives. People who attended that presentation continue to contact us almost daily. The Open Center is a non-profit Holistic Learning Center, featuring a wide variety of presentations and workshops. 83 Spring St., NY, NY 10012. 212 219-2527. FERNANDEZ, MEIER, AND RILEY AT EWA MEETING At the Education Writers Conference in Boston, I got to meet the Secretary of Education, Richard W. Riley. After he talking about the possibility of new national standards, a quasi-national curriculum, I told him that there were hundreds of thousands of homeschoolers and thousands of alternative schools that did not want a curriculum imposed on them. I asked him how he would approach that fact. He responded that "When we establish these standards they will uplift us all." I did not find that reply comforting. On the other hand, I am pleased that Madelin Kunin, former governor of Vermont, is the new Deputy Secretary of Education. She once spoke at the graduation of Shaker Mountain School when I was Headmaster, and is quite familiar with educational alternatives. -

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

Read Book \\ Articles on Independent Schools in Devon, Including: United Services College, Blundell's School, Plymouth Colle

GDVRUFG44KLN » Book » Articles On Independent Schools In Devon, including: United Services College, Blundell's School,... Read PDF Online ARTICLES ON INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS IN DEVON, INCLUDING: UNITED SERVICES COLLEGE, BLUNDELL'S SCHOOL, PLYMOUTH COLLEGE, THE SMALL SCHOOL, WEST BUCKLAND SCHOOL, EDGEHILL COLLEGE, SANDS SCHOOL, KELLY COLLEGE To read Articles On Independent Schools In Devon, including: United Services College, Blundell's School, Plymouth College, The Small School, West Buckland School, Edgehill College, Sands School, Kelly College PDF, you should click the web link beneath and download the document or gain access to additional information which are related to ARTICLES ON INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS IN DEVON, INCLUDING: UNITED SERVICES COLLEGE, BLUNDELL'S SCHOOL, PLYMOUTH COLLEGE, THE SMALL SCHOOL, WEST BUCKLAND SCHOOL, EDGEHILL COLLEGE, SANDS SCHOOL, KELLY COLLEGE ebook. Download PDF Articles On Independent Schools In Devon, including: United Services College, Blundell's School, Plymouth College, The Small School, West Buckland School, Edgehill College, Sands School, Kelly College Authored by Books, Hephaestus Released at 2016 Filesize: 8.43 MB Reviews A high quality pdf and also the typeface used was exciting to see. it absolutely was writtern really properly and useful. I am quickly could get a delight of looking at a composed pdf. -- Justina K unze I just began looking over this pdf. It is amongst the most remarkable publication i have got study. I am pleased to let you know that this is the greatest book i have got read inside my personal life and can be he very best pdf for at any time. -- Dr. Davonte Schmidt MD Excellent eBook and useful one. -

Downloading the Same Thing to Their E-Reader Once They've Bought One in the First Place

FREE Follow us on March 2015 www.bidefordbuzz.org.uk A free commuBnity newislettder for Beidefordf, Northoam, Applredore, Wdestwar d HBo!, Lundyu and vilzlages wez st as far as Hartland Memories of Bideford Hospital But when and who? Any ideas? Read more about this inside on page 12 ... n o s n e B - e i l s e L a p i l l i h P f o y s e t r u o c o t o h P A 20 page Bumper edition including: Bee’s Knees ✦ From Hungarian refugee to bistro This month we launch an exciting new idea. “Buzz” would like to canvass readers - what ✦ owner. do you think is ‘The Bee’s Knees’ in Bideford ? ✦ This year's Manor Court ceremony. It could be a walk, a view, a building, a favourite shop, any aspect of Bideford that Extra Book News. you feel is unique, special, or loved. ✦ Send your ideas to us - contact details below. ✦ Plus our regular items. T Bideford Buzz is produced by a team of volunteers with practical assistance from Torridge District Council, Torridge Voluntary Services, Bideford Town Council, Z C Bideford Bridge Trust, South West Foundation, Devon County Council & Bideford Freemasons. If you are interested in helping to produce or distribute this newsletter A Z T we would be pleased to hear from you. Please note that for advertisements there is a charge from £15 per box per month. Cheques payable to Bideford Buzz Newsletter U N Group. All items for inclusion should be sent by the 15th of the month to the Editor, Rose Arno. -

Sands School – Student Interviews)

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Trust me, I‟m a student: An exploration through Grounded Theory of the student experience in two small schools being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Max A. Hope, B.A. (York) September 2010 Abstract The majority of literature about democratic education has been written from the perspective of teachers or educators. This thesis is different. It has a clear intention to listen to and learn from the experiences of students. Empirical research was conducted using grounded theory methodology. Two secondary schools were selected as cases: one was explicitly democratic; the other was underpinned by democratic principles. Extensive data sets were gathered. This included conducting interviews with eighteen students; undertaking observations of lessons, meetings and social spaces; and holding informal conversations with teachers, staff and other students. Documentary information was also collected. All data were systematically analysed until the researcher was able to offer a conceptual model through which to understand the student experience. This thesis argues that the quality of learning is likely to improve if schools pay attention to how students feel. In particular, students with a strong sense of belonging and those who feel accepted as individuals are likely to be less defensive, more open, and more able to be constructive members of a school community. A theoretical model is presented which identifies key factors which contribute to these processes. This model presents a challenge to the way in which school effectiveness is assessed within the current education system. Acknowledgements First and foremost, my thanks must go to the staff and students at two small alternative schools – Sands School in Ashburton, Devon and The Small School in Hartland, Devon. -

Youth Workers State Education

© YOUTH & POLICY, 2012 Youth Work and State Education: Should Youth Workers Apply to Set Up a Free School? Max Hope Abstract: The UK Coalition Government’s new policy on Free Schools presents a dilemma for youth workers. Is there any possibility of establishing a ‘youth worker – led Free School’ based on the principles and values of youth work? Do the potential pitfalls make this too risky to even consider? This article outlines the policy on Free Schools, and assesses the potential for youth workers to run a radical and creative alternative to mainstream education. It includes a summary of the key issues to consider, and concludes with a suggestion about which types of Free Schools are most likely to be consistent with the values and principles of youth work. Key words: Free schools, policy, state education, ethics, values. BRITAIN IS IN ITS deepest recession since the 1930s and the Coalition Government has responded by, amongst other things, cutting funding to public services. Some argue that this is a purely pragmatic response to the debt crisis; others accuse the Conservatives of hiding behind the economy whilst fulfilling their political ambitions of rolling back the state (Sparrow, 2010). Whatever the reasons, the impact remains the same. Youth and community work is under threat. Youth centres are shutting down. Frontline services are being streamlined. Youth workers are being made redundant (Watson, 29 June 2010). Fewer young people are able to access youth work and youth workers. Yet at the same time, the Coalition Government has announced new policies – the Big Society, the Localism bill, the Academies Act, to name but a few. -

THE HARTLAND POST First Published in 2015, in the Footsteps of Th Omas Cory Burrow’S “Hartland Chronicle” (1896-1940) and Tony Manley’S “Hartland Times” (1981-2014)

THE HARTLAND POST First published in 2015, in the footsteps of Th omas Cory Burrow’s “Hartland Chronicle” (1896-1940) and Tony Manley’s “Hartland Times” (1981-2014) Issue No. 15 Summer 2019 £1 ‘A Prevailing Wind’ by Merlyn Chesterman THE HARTLAND POST A quarterly news magazine for Hartland and surrounding area Issue No. 15 Summer 2019 Printed by Jamaica Press, Published by Th e Hartland Post All communications to: Th e Editor, Sally Crofton, Layout: Kris Tooke 102 West Street, EX39 6BQ Hartland. Cover artwork: Laura Zalewski Tel. 01237 441617 Email: [email protected] Website: John Zalewski ANNOUNCEMENTS 1st CUCKOO Ella Mary Jennings - Leslie & Ann Deadman of West Leslie Deadman of West Bursdon Farm heard the fi rst Cuckoo Bursdon Farm are pleased to announce the arrival of their fi rst of 2019 on Good Friday morning 19th April, whilst walking grandchild. Ella Mary Jennings was born at home in Launceston in his woods. on Tuesday May 7th, weighing 6lb 9oz. Parents Katy & Barry Jennings are delighted to welcome their daughter, as are her Uncles John and Peter Deadman. Ella is also a fi rst grandchild for Steve & Julia Jennings of Chilsworthy and another great grandchild to Rhoda Jennings of Bradworthy. Ann & Leslie are also very happy to announce the engagement of son Peter to Alice Lake on Friday May 3rd. Nicky Hedges would like to say a big 'Th ank You' to everyone for all their support, kind wishes and cards following the passing of her dad Ken. Gordon Cross passed away in his sleep on 31 January. -

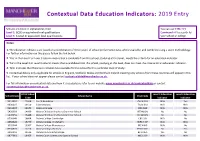

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2019 Entry

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2019 Entry Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. UCAS School Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Code School Name Post Code Code Indicator Indicator 9314901 12474 16-19 Abingdon OX14 1JB N/A Yes 9336207 19110 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ N/A N/A 9316007 15144 Abacus College OX3 9AX