The Significance of Food for Mystics in the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friars' Bookshelf 385

The Lie About the West. A Response to Professor Toynbee's challenge. By Douglas Jerrold. New York, Sheed and Ward, 1954. pp. 85. $1.75. Will the civilization of Europe and the \.Vestern Hemisphere decline and die like all others of the past, or will it rally and live? Professor Arnold Toynbee, the eminent British historian, proponent of the theory of challenge and response as the key to history, has proposed a possible answer in a recent book, The World and the T~ est. He views the present world crisis as the result of a "response" by the rest of the world (Russia and the Orient) to the "challenge" of continued Western aggression, both military and technological. Draw ing a parallel with the declining Roman Empire, which after numerous aggressions was converted to eastern religions-principally and finally to Christianity, he thinks it probable that the West will be converted to a new religion coming from the Orient. This will not be Commun ism, he adds in a letter to The Times Literary Su.pplement (April 16, 1954), but an entirely new religion which he hopes will retain the Christian belief in God as Love but will discard the notion of a jealous God and a chosen people in favor of a more universal view, borrowed perhaps from Indian Buddhism. Mr. Douglas Jerrold, another English historian, has called this doctrine a lie in his "response to Professor Toynbee "s challenge." It is a lie against fact, against reason, and against faith. It is against fact because the West was not an aggressor but was on the defensive for a thousand years against the Northmen, Magyars, and Turks; because Christianity was not and is not one of many "oriental re ligions" but an historical one which arose within the Roman Empire and was spread by Roman citizens; because Roman civilization was not spread merely by force of arms. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

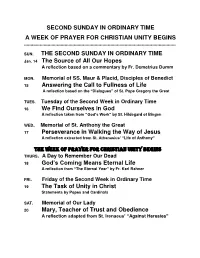

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. ‘Medicine’, in William Morris, ed., The American Heritage Dictionary (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976); ‘medicine n.’, in The Oxford American Dictionary of Current English, Oxford Reference Online (Oxford University Press, 1999), University of Toronto Libraries, http://www.oxfordreference.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/ views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t21.e19038 [accessed 22 August 2008]. 2. The term doctor was derived from the Latin docere, to teach. See Vern Bullough, ‘The Term Doctor’, Journal of the History of Medicine, 18 (1963): 284–7. 3. Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter, Patient’s Progress: Doctors and Doctoring in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Polity, 1989), p. 11. 4. I am indebted to many previous scholars who have worked on popular healers. See particularly work by scholars such as Margaret Pelling, Roy Porter, Monica Green, Andrew Weir, Doreen Nagy, Danielle Jacquart, Nancy Siraisi, Luis García Ballester, Matthew Ramsey, Colin Jones and Lawrence Brockliss. Mary Lindemann, Merry Weisner, Katharine Park, Carole Rawcliffe and Joseph Shatzmiller have brought to light the importance of both the multiplicity of medical practitioners that have existed throughout history, and the fact that most of these were not university trained. This is in no way a complete list of the authors I have consulted in prepa- ration of this book; however, their studies have been ground-breaking in terms of stressing the importance of popular healers. 5. This collection contains excellent specialized articles on different aspects of female health-care and midwifery in medieval Iberia, and Early Modern Germany, England and France. The articles are not comparative in nature. -

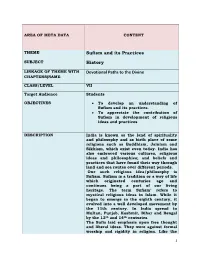

Sufism and Its Practices History Devotional Paths to the Divine

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME Sufism and its Practices SUBJECT History LINKAGE OF THEME WITH Devotional Paths to the Divine CHAPTERS(NAME CLASS/LEVEL VII Target Audience Students OBJECTIVES To develop an understanding of Sufism and its practices. To appreciate the contribution of Sufism in development of religious ideas and practices DESCRIPTION India is known as the land of spirituality and philosophy and as birth place of some religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which exist even today. India has also embraced various cultures, religious ideas and philosophies; and beliefs and practices that have found their way through land and sea routes over different periods. One such religious idea/philosophy is Sufism. Sufism is a tradition or a way of life which originated centuries ago and continues being a part of our living heritage. The term Sufism’ refers to mystical religious ideas in Islam. While it began to emerge in the eighth century, it evolved into a well developed movement by the 11th century. In India spread to Multan, Punjab, Kashmir, Bihar and Bengal by the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sufis laid emphasis upon free thought and liberal ideas. They were against formal worship and rigidity in religion. Like the 1 Bhakti saints, the Sufis too interpreted religion as ‘love of god’ and service of humanity. Sufis believe that there is only one God and that all people are the children of God. They also believe that to love one’s fellow men is to love God and that different religions are different ways to reach God. -

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan By Zainub Beg A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, K’jipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies. December 2020, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Zainub Beg, 2020 Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Reem Meshal Examiner Approved: Dr. Sailaja Krishnamurti Reader Date: December 21, 2020 1 Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan by Zainub Beg Abstract Abida Parveen, often referred to as the Queen of Sufi music, is one of the only female qawwals in a male-dominated genre. This thesis will explore her performances for Coke Studio Pakistan through the lens of gender theory. I seek to examine Parveen’s blurring of gender, Sufism’s disruptive nature, and how Coke Studio plays into the two. I think through the categories of Islam, Sufism, Pakistan, and their relationship to each other to lead into my analysis on Parveen’s disruption in each category. I argue that Parveen holds a unique position in Pakistan and Sufism that cannot be explained in binary terms. December 21, 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................. -

Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 10-2007 Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt Minnesota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Zierdt, Ginger L., "Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 60. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Women in History Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt "Wisdom teaches in the light of love, and bids me tell how I was brought into this my gift of vision ..." (Hildegard) Visionary Prodigy Hildegard of Bingen was born in Bermersheim, Germany near Alzey in 1098 to the nobleman Hildebert von Bermersheim and his wife Mechthild, as their tenth and last child. Hildegard was brought by her parents to God as a "tithe" and determined for life in the Order. How ever, "rather than choosing to enter their daughter formally as a child in a convent where she would be brought up to become a nun (a practice known as 'oblation'), Hildegard's parents had taken the more radical step of enclosing their daughter, apparently for life, in the cell of an anchoress, Jutta, attached to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg" (Flanagan, 1989, p.