Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

He Sanctuary Series

T S S HE ANCTUARY ERIES A Compilation of Saint U News Articles h ON THE g Saints Depicted in the Murals & Statuary of Saint Ursula Church OUR CHURCH, LIVE IN HRIST, A C LED BY THE APOSTLES O ver the main doors of St. Ursula Church, the large window pictures the Apostles looking upward to an ascending Jesus. Directly opposite facing the congregation is the wall with the new painting of the Apostles. The journey of faith we all make begins with the teaching of the Apostles, leads us through Baptism, toward altar and the Apostles guiding us by pulpit and altar to Christ himself pictured so clearly on the three-fold front of the Tabernacle. The lively multi-experiences of all those on the journey are reflected in the multi-colors of the pillars. W e are all connected by Christ with whom we journey, He the vine, we the branches, uniting us in faith, hope, and love connected to the Apostles and one another. O ur newly redone interior, rededicated on June 16, 2013, was the result of a collaboration between our many parishioners, the Intelligent Design Group (architect), the artistic designs of New Guild Studios, and the management and supervision of many craftsmen and technicians by Landau Building Company. I n March 2014, the Landau Building Company, in a category with four other projects, won a first place award from the Master Builders Association in the area of “Excellence in Craftsmanship by a General Contractor” for their work on the renovations at St. Ursula. A fter the extensive renovation to the church, our parish community began asking questions about the Apostles on the Sanctuary wall and wishing to know who they were. -

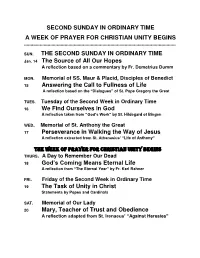

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

Catholic Liturgical Calendar †

Catholic Liturgical Calendar January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018 FOR THE DIOCESES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2018 ⚭ † ☧ 2 JANUARY 2018 1 Mon SOLEMNITY OF MARY, THE HOLY MOTHER OF GOD white Rank I The Octave Day of the Nativity of the Lord Solemnity [not a Holyday of Obligation] Nm 6:22-27/Gal 4:4-7/Lk 2:16-21 (18) Pss Prop Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God (Theotokos) The Octave Day of the Nativity of the Lord Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God (Theotokos) “From most ancient times the Blessed Virgin has been venerated under the title ‘God- bearer’(Theotokos)” (Lumen Gentium, no. 66). All of the Churches recall her memory under this title in their daily Eucharistic prayers, and especially in the annual celebration of Christmas. The Virgin Mary was already venerated as Mother of God when, in 431, the Council of Ephesus acclaimed her Theotokos (God-bearer). As the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary has a unique position among the saints, indeed, among all creatures. She is exalted, yet still one of us. Redeemed by reason of the merits of her Son and united to Him by a close and indissoluble tie, she is endowed with the high office and dignity of being the Mother of the Son of God, by which account she is also the beloved daughter of the Father and the temple of the Holy Spirit. Because of this gift of sublime grace she far surpasses all creatures, both in heaven and on earth. At the same time, however, because she belongs to the offspring of Adam she is one with all those who are to be saved. -

A Conductor's Guide to the Music of Hildegard Von

A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THE MUSIC OF HILDEGARD VON BINGEN by Katie Gardiner Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University July 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Carolann Buff, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Christopher Albanese ______________________________________ Giuliano Di Bacco ______________________________________ Dominick DiOrio June 17, 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Katie Gardiner iii For Jeff iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge with gratitude the following scholars and organizations for their contributions to this document: Vera U.G. Scherr; Bart Demuyt, Ann Kelders, and the Alamire Foundation; the Librarian Staff at the Cook Music Library at Indiana University; Brian Carroll and the Indiana University Press; Rebecca Bain; Nathan Campbell, Beverly Lomer, and the International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies; Benjamin Bagby; Barbara Newman; Marianne Pfau; Jennifer Bain; Timothy McGee; Peter van Poucke; Christopher Page; Martin Mayer and the RheinMain Hochschule Library; and Luca Ricossa. I would additionally like to express my appreciation for my colleagues at the Jacobs School of Muisc, and my thanks to my beloved family for their fierce and unwavering support. I am deeply grateful to my professors at Indiana University, particularly the committee members who contributed their time and expertise to the creation of this document: Carolann Buff, Christopher Albanese, Giuliano Di Bacco, and Dominick DiOrio. A special debt of gratitude is owed to Carolann Buff for being a supportive mentor and a formidable editor, and whose passion for this music has been an inspiration throughout this process. -

John of Salisbury's Relics of Saint Thomas Becket and Other Holy Martyrs 163

Aus dem Inhalt der folgenden Bände: Band 26 2013 Reinhard Bleck, Reinmar der Alte, Lieder mit historischem Hintergrund 2013 (MF 156,10; 167,31; 180,28; 181,13) · Dina Aboul Fotouh Salama, Die Kolonialisierung des weiblichen Körpers in der spätmittelalterlichen Versnovelle „Die heideninne“ Internationale Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Mittelalterforschung Band 26 Werner Heinz, Heilige Längen: Zu den Maßen des Christus- und des Mariengrabes in Bebenhausen George Arabatzis, Nicephoros Blemmydes’ Imperial Statue: Aristotelian Politics as Kingship Morality in Byzantium Francesca Romoli, La funzione delle citazioni bibliche nell'omiletica e nella letteratura di direzione spirituale del medioevo slavo orientale (XII-XIII sec.) Connie L. Scarborough, Educating Women for the Benefit of Man and Society: Castigos y dotrinas que un sabio daba a sus hijas and La perfecta casada Beihefte zur Mediaevistik: Elisabeth Mégier, Christliche Weltgeschichte im 12. Jahrhundert: Themen, Variationen und Kontraste. Untersuchungen zu Hugo von Fleury, Orderi- cus Vitalis und Otto von Freising (2010) Andrea Grafetstätter / Sieglinde Hartmann / James Ogier (eds.), Islands and Cities in Medieval Myth, Literature, and History. Papers Delivered at the International Medieval Congress, University of Leeds, in 2005, 2006, and 2007 (2011) Olaf Wagener (Hrsg.), „vmbringt mit starcken turnen, murn“. Ortsbefesti- gungen im Mittelalter (2010) Hiram Kümper (Hrsg.), eLearning & Mediävistik. Mittelalter lehren und lernen im neumedialen Zeitalter (2011) Begründet von Peter Dinzelbacher -

Corpus Christi

Sacred Heart Catholic Church Mission: We are a dynamic and welcoming Catholic community, cooperating with God’s grace for the salvation of souls, serving those in need, and spreading the Good News of Jesus and His Love. Iglesia del Sagrado Corazón Misión: somos una comunidad católica dinámica y acogedora, cooperando con la gracia de Dios para la salvación de las almas, sirviendo a aque- llos en necesidad, y compartiendo la Buena Nueva de Jesús y Su amor. Pastoral Team Pastor: Rev. Fr. Michael Niemczak Deacons: Rev. Mr. Juan A. Rodríguez Rev. Mr. Michael Rowley Masses/Misas Monday: 5:30p.m. Tuesday: No Mass Wednesday: 12:10p.m. Thursday/jueves: 5:30p.m. (Spanish / en español) Friday: 12:10p.m. Saturday/sábado: (Vigil/vigilia) 6:00p.m. (Spanish / en español) Sunday: 8:30a.m., 10:30a.m. & 5:00p.m. At this time, we will be authorized 200 parishioners per Mass in the church. Hasta nuevo aviso, solo podemos tener 200 feligreses dentro de la iglesia por cada Misa. Church Address/dirección 921 N. Merriwether St. Clovis, N.M. 88101 Phone/teléfono: (575)763-6947 June 6th, 2021 / 6 de junio, 2021 Fax: (575)762-5557 Email: Corpus Christi [email protected] [email protected] Confession Times/ Eucharistic Adoration/ Website: www.sacredheartclovis.com Confesiones Adoración del Santísimo facebook: Mon. & Thurs./lunes y jueves Thursday / jueves www.facebook.com/sacredheartclovis 4:45p.m. - 5:20p.m. 12:00p.m. to 5:15p.m. Food Pantry/Despensa: Wed. & Fri./miércoles y viernes Friday / viernes 2nd & 4th Saturday/2˚ y 4˚ sábado: 11:30a.m. -

Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 2007 Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart Duquesne University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Sobehart, Helen C., "Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 10. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart "You know, Hildegard, I didn't ask for this calling to support the cause of women." "Well I didn't ask for what happened to me either, Helen. Ijust happened to be born the tenth child of a wealthy family in the twelfth century. Do you know where the word "tithe" comes from? In my day, the 'tenth' child was 'donated'to the church. So stop whining and let's get on with this story." "Kind of cheeky for a 12th century nun, aren't you?" "We mystics can take on the vernacular of the time-should that be so surpris ing? In fact, one of my biographers correctly observed that there were 'limits to my patience and humility, and that 'meek' and 'ordinary' were the last words to describe me" (Flanagan, 1998, p. -

Creation Care Season September 30 – November 30 Creation Care

Creation Care Season Creation Care Season September 30 – November 30 September 30 – November 30 Diocesan Convention 2010 voted to encourage every Diocesan Convention 2010 voted to encourage every congregation to observe and celebrate a season of thanksgiving congregation to observe and celebrate a season of thanksgiving and wonder for the life-giving seasons of God’s creation. and wonder for the life-giving seasons of God’s creation. Clean air and clear water are threatened by human neglect, Clean air and clear water are threatened by human neglect, natural resource consumption, and pollution caused by burning natural resource consumption, and pollution caused by burning fossil fuels. fossil fuels. The health of the Earth affects us all, but especially vulnerable The health of the Earth affects us all, but especially vulnerable poor, sick, and young people. poor, sick, and young people. Creation Care Season calls us to act on behalf of our Creating Creation Care Season calls us to act on behalf of our Creating God, the Earth, our children, and other people by adopting God, the Earth, our children, and other people by adopting creation care holy habits such as: creation care holy habits such as: • Designate a Sunday between Sept. 30—Nov. 30 as Creation • Designate a Sunday between Sept. 30—Nov. 30 as Creation Care Sunday, asking people to give generously to support a Care Sunday, asking people to give generously to support a Creation Care project in the parish, community, or Diocese. Creation Care project in the parish, community, or Diocese. • Explore ways your household can save energy and reduce its • Explore ways your household can save energy and reduce its carbon footprint. -

The Greatest Faith Ever Preached Sunday December 30, 2012 We've

The Greatest Faith Ever Preached Sunday December 30, 2012 We’ve had a great year as a church in 2012. God has been very gracious to us. We’ve seen wonderful growth in reaching out to people • GodTV • We were part of VisionIndia training up 8,600 young people from about 15 states across North India. In addition, 12,000 sets of our Hindi publications (12 titles) i.e. 1,44,000 copies of our publications distributed at VisionIndia itself! • Short Term Bible college at Champa, where we graduated 45 students • Missions Trips by our young people to Chattarpur • Two more new locations in Bangalore East and West • APC-Mangalore moved into Mangalore city and encouraging response from students there • APC moved into a new office • …and so much more… As we look ahead to 2013, we as a church must be ready to reach out both in our city and across our nation. Jesus gave one of the indicators of the end of this age. He said “And this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in all the world as a witness to all the nations, and then the end will come.” (Matthew 24:14) This morning we are going to talk about “The Greatest Faith Ever Preached” Mark 16:14-20 There were 11 unbelieving disciples. Jesus rebuked them for their unbelief and hardness of heart – even after being with Jesus for 3 years, seeing and hearing all that He did and taught – they still doubted His resurrection. To these men, He gave the great commission – to take the Gospel to the ends of the world! From a group of 11 unbelieving disciples, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, has spread to the nations.