The Development of the Prophetic Voice of Hildegard of Bingen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

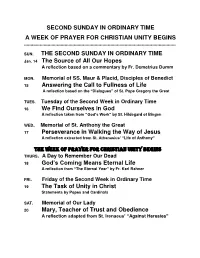

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

13Th Century Psaltery Musical Instrument Document

Copyright Barry Ebersole 2003 Cantigas de Santa Maria Psaltery (13th Century) pg 1 The Psaltery or Kanon (Canon -- Canale -- Qanon) The Cantigas de Santa Maria manuscript ca. 1260. Here are two kanons being tuned and played. There are many shapes of psaltrys, however this one resembles the modern qunan shape and is interesting in many ways. This is the model for reproduction. The tuning wrench being used by the left hand figure should be noted -- shows use of metal tuning pins. Copyright Barry Ebersole 2003 Cantigas de Santa Maria Psaltery (13th Century) pg 2 French, Lambertus Treatise, 13th Century ("King David with Musicians" in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, MS. lat.6755(2), fol. Av). The psaltry in this picture shows the empty area (the corner where the string length is too short for use) This is the same shape and type as in the Cantigas illustration (the one chosen for reproduction). A double row of pegs can be seen – this clearly incicates double stringing even though the lines for strings do not show it. Psaltries come in many shapes and sizes. Music and Her Attendants. Fourteenth-century Italian miniature illustrating the De aritlumetica of Boethius. A pig snout psaltry. Copyright Barry Ebersole 2003 Cantigas de Santa Maria Psaltery (13th Century) pg 3 Hans Memling 1480 – a psaltery on the far left. Two inches thick – an on-going theme. 12th century psaltry – an early European representation. This is so similar to the period instrument I have in my personal collection dated 1650. Note this three dimentional carving clearly shows a thickness of about two inches. -

Francisco García Fitz

SUMMARY I PART. THE PAST INTERROGATED AND UNMASKED 25-53 Battle in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula: 11th to 13th century Castile-Leon. State of the art Francisco García Fitz 55-95 The Gothic Novel ‘Curial e Güelfa’: an erudite Creation by Milà i Fontanals Rosa Navarro 97-116 Medievalism in contemporary Fantasy: a new Species of Romance Mladen M. Jakovljević, Mirjana N. Lončar-Vujnović 117-153 Medieval History in the Catalan Research Institutions (2003-2009) Flocel Sabaté II PART. THE PAST STUDIED AND MEASURED 157-169 Conspiring in Dreams: between Misdeeds and saving one’s Soul Andrea Vanina Neyra 171-189 ‘De origine civitatis’. The building of Civic Identity in Italian Communal Chronicles (12th-14th century) Lorenzo Tanzini 191-213 The Identity of the urban ‘Commoners’ in 13th century Flanders Jelle Haemers 215-229 The ‘Petit Thalamus’ of Montpellier. Moving mirror of an Urban Political Identity Vincent Challet 231-243 Is there a model of Political Identity in the Small Cities of Portugal in the Late Middle Ages? A preliminary theoretical approach Adelaide Millán da Costa 245-265 ‘Saben moltes coses contra molts convessos de Xàtiva e de València’. Converted Jews IMAGO TEMPORIS Medium Aevum in the Kingdom of Valencia: Denunciation and social Betrayal in Late 15th century Xàtiva Juan Antonio Barrio 267-289 Seigneurial Pressure: external Constrictions and Stimuli in the Construction of Urban Collective Identities in 15th century Castile José Antonio Jara 291-312 Urban Identity in Castile in the 15th century María Asenjo 313-336 Identity and Difference among the Toulouse Elite at the end of the Middle Ages: Discourse, Representations and Practices Véronique Lamazou-Duplan ART HE AST XPLAINED AND ECREATED IMAGO TEMPORIS III P . -

A Conductor's Guide to the Music of Hildegard Von

A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THE MUSIC OF HILDEGARD VON BINGEN by Katie Gardiner Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University July 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Carolann Buff, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Christopher Albanese ______________________________________ Giuliano Di Bacco ______________________________________ Dominick DiOrio June 17, 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Katie Gardiner iii For Jeff iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge with gratitude the following scholars and organizations for their contributions to this document: Vera U.G. Scherr; Bart Demuyt, Ann Kelders, and the Alamire Foundation; the Librarian Staff at the Cook Music Library at Indiana University; Brian Carroll and the Indiana University Press; Rebecca Bain; Nathan Campbell, Beverly Lomer, and the International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies; Benjamin Bagby; Barbara Newman; Marianne Pfau; Jennifer Bain; Timothy McGee; Peter van Poucke; Christopher Page; Martin Mayer and the RheinMain Hochschule Library; and Luca Ricossa. I would additionally like to express my appreciation for my colleagues at the Jacobs School of Muisc, and my thanks to my beloved family for their fierce and unwavering support. I am deeply grateful to my professors at Indiana University, particularly the committee members who contributed their time and expertise to the creation of this document: Carolann Buff, Christopher Albanese, Giuliano Di Bacco, and Dominick DiOrio. A special debt of gratitude is owed to Carolann Buff for being a supportive mentor and a formidable editor, and whose passion for this music has been an inspiration throughout this process. -

Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 10-2007 Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt Minnesota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Zierdt, Ginger L., "Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 60. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Women in History Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt "Wisdom teaches in the light of love, and bids me tell how I was brought into this my gift of vision ..." (Hildegard) Visionary Prodigy Hildegard of Bingen was born in Bermersheim, Germany near Alzey in 1098 to the nobleman Hildebert von Bermersheim and his wife Mechthild, as their tenth and last child. Hildegard was brought by her parents to God as a "tithe" and determined for life in the Order. How ever, "rather than choosing to enter their daughter formally as a child in a convent where she would be brought up to become a nun (a practice known as 'oblation'), Hildegard's parents had taken the more radical step of enclosing their daughter, apparently for life, in the cell of an anchoress, Jutta, attached to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg" (Flanagan, 1989, p. -

Jeremy Montagu Some Mss. in the British Library with Instruments Page 1 of 2

Jeremy Montagu Some Mss. In the British Library with Instruments Page 1 of 2 Some Manuscripts in the British Library with Illustrations of Musical Instruments and a few other sources that I have found FoMRHIQ 2, January 1976,Comm. 8 Arundel 83. Conflation of two English Psalters, East Anglia, c.1310. The second half is known as the de Lisle Psalter. Good source. Includes: long trumpets, harps, citole, bagpipe, bells, fiddle, portative, psaltery, duct flute, pipe & tabor. Cotton, Tib.C.vi. Psalter, mid 11th c. f.30 is well-known; the rest is the usual Boethius improbabilities of the period. Egerton 1139. Queen Melissander’s Psalter, Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, c.1140. The only instrument is a good harp, available asa postcard. The ivory cover is well known: King David playing what might be a dulcimer. Harley 2804. German Bible, 1148. f.3 has a not very good David and musicians. Harley 4425. La Roman de la Rose, pre-1500. 2 folios with music parties. Royal 2.A.xvi. Psalter time of Henry VIII, with annotations by him. Harp, pipe& tabor, short trumpet, dulcimer. Interesting that Henry is one of the musicians (and his fool shuts his ears to avoid his playing). Royal 2.A.xxii. The Westminster Psalter, late 12th c. David with harp and bells (postcard available), another harp. Interesting in that Westminster Abbey has a very similar hemi- spherical bell in the Undercroft exhibition room. Royal 2.B.vii. The Queen Mary Psalter, English early 14th c. well known source with a lot of material, but none quite as good and clear as in other East Anglian psalters (e.g. -

Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 2007 Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart Duquesne University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Sobehart, Helen C., "Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 10. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart "You know, Hildegard, I didn't ask for this calling to support the cause of women." "Well I didn't ask for what happened to me either, Helen. Ijust happened to be born the tenth child of a wealthy family in the twelfth century. Do you know where the word "tithe" comes from? In my day, the 'tenth' child was 'donated'to the church. So stop whining and let's get on with this story." "Kind of cheeky for a 12th century nun, aren't you?" "We mystics can take on the vernacular of the time-should that be so surpris ing? In fact, one of my biographers correctly observed that there were 'limits to my patience and humility, and that 'meek' and 'ordinary' were the last words to describe me" (Flanagan, 1998, p.