Shelter and NFI Cluster Evaluation Cyclone Giri Response, Myanmar October 2010 to January 2011 July 2011 Kerren Hedlund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Disaster Management

Lesson Learned Presentation Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar 1 Contents • Hazards Profile of Myanmar • Legislation • National Framework • Institutional Arrangement • AADMER Implementation and ASEAN Related Activities • DRR Activities of Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement • Experiences • Lesson Learned • Way Forward 2 Hazard Profile of Myanmar 33 Hazard Profile (Fire) (Flood) (Storm) (Earthquake) (Tsunami) (Landslide) (Drought) (Epidemic) 4 Potential Hazards and Prone Areas in Myanmar Fire All round the country Flood Annual flood occur in Kayin State, Bago Region, Mandalay Region, Ayaeyarwaddy Region. Especially townships and villages which are situated along the rivers banks of Ayaryarwaddy, Sittaung, Thanlwin, Madauk and Shwe Kyin. Cyclone Thanintharyi region, Mon State, Rakhine State, Yangon Region and AyaeyarWaddy Region 55 Earthquake can occur around the country, Nay Pyi Taw, Bago, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions and Shan State are earthquake prone areas. Tsunami Costal areas such as Rakhine and Mon States and Ayaeyarwaddy, Yangon and Thanintharyi Regions Drought Central Myanmar (Sagaing, Magwe,and Mandalay regions) Landslide Hilly Region (Kachin,Chin, Shan and Rakhine 66 St t d Th i th i Ri) Legislation 77 Legislation • The Disaster Management Law with (9) Chapters has been enacted on 31st July 2013. • Title and Definition • Objectives (a) to implement natural disaster management programmes systematically and expeditiously in order to reduce disaster risks; (b) -

Download Report

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Understanding the Fish Market System in Kyauk Phyu Township Rakhine State. Annex to the Final report to DfID Post Giri livelihoods recovery, Kyaukphyu Township, Rakhine State February 14 th 2011 – November 13 th 2011 August 2011 1 Background: Rakhine has a total population of 2,947,859, with an average household size of 6 people, (5.2 national average). The total number of households is 502,481 and the total number of dwelling units is 468,000. 1 On 22 October 2010, Cyclone Giri made landfall on the western coast of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The category four cyclonic storm caused severe damage to houses, infrastructure, standing crops and fisheries. The majority of the 260,000 people affected were left with few means to secure an income. Even prior to the cyclone, Rakhine State (RS) had some of the worst poverty and social indicators in the country. Children's survival and well-being ranked amongst the worst of all State and Divisions in terms of malnutrition, with prevalence rates of chronic malnutrition of 39 per cent and Global Acute Malnutrition of 9 per cent, according to 2003 MICS. 2 The State remains one of the least developed parts of Myanmar, suffering from a number of chronic challenges including high population density, malnutrition, low income poverty and weak infrastructure. The national poverty index ranks Rakhine 13 out of 17 states, with an overall food poverty headcount of 12%. The overall poverty headcount is 38%, in comparison the national average of poverty headcount of 32% and food poverty headcount of 10%. -

Prediction of Landfalling Tropical Cyclones Over East Coast of India in the Global Warming Era

Prediction of Landfalling Tropical Cyclones over East Coast of India in the Global Warming Era U. C. Mohanty School of Earth, Ocean and Climate Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar Outline of Presentation • Introduction • Mesoscale modeling of TCs with MM5, ARW, NMM and HWRF systems • Conclusions and Future Directions Natural disasters Hydrometeorologi- Geophysical cal Disasters: Disasters: Earthquakes Cyclones Avalanches Flood Land slides Drought Volcanic eruption Tornadoes Dust storms Heat waves Cold waves Warmest 12 years: 1998,2005,2003,2002,2004,2006, 2001,1997,1995,1999,1990,2000 Global warming Period Rate 25 0.1770.052 50 0.1280.026 100 0.0740.018 150 0.0450.012 Years /decade IPCC Introduction • Climate models are becoming most important tools for its increasing efficiency and reliability to capture past climate more realistically with time and capability to provide future climate projections. • Observations of land based weather stations in global network confirm that Earth surface air temperature has risen more than 0.7 ºC since the late 1800s to till date. This warming of average temperature around the globe has been especially sharp since 1970s. • The IPCC predicted that probable range of increasing temperature between 1.4 - 5.8 ºC over 1990 levels by the year 2100. Contd…… • The warming in the past century is mainly due to the increase of green house gases and most of the climate scientists have agreed with IPCC report that the Earth will warm along with increasing green house gases. • In warming environment, weather extremes such as heavy rainfall (flood), deficit rainfall (drought), heat/cold wave, storm etc will occur more frequent with higher intensity. -

Growth of Cyclone Viyaru and Phailin – a Comparative Study

Growth of cyclone Viyaru and Phailin – a comparative study SDKotal1, S K Bhattacharya1,∗, SKRoyBhowmik1 and P K Kundu2 1India Meteorological Department, NWP Division, New Delhi 110 003, India. 2Department of Mathematics, Jadavpur University, Kolkata 700 032, India. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] The tropical cyclone Viyaru maintained a unique quasi-uniform intensity during its life span. Despite beingincontactwithseasurfacefor>120 hr travelling about 2150 km, the cyclonic storm (CS) intensity, once attained, did not intensify further, hitherto not exhibited by any other system over the Bay of Bengal. On the contrary, the cyclone Phailin over the Bay of Bengal intensified into very severe cyclonic storm (VSCS) within about 48 hr from its formation as depression. The system also experienced rapid intensification phase (intensity increased by 30 kts or more during subsequent 24 hours) during its life time and maximum intensity reached up to 115 kts. In this paper, a comparative study is carried out to explore the evolution of the various thermodynamical parameters and possible reasons for such converse features of the two cyclones. Analysis of thermodynamical parameters shows that the development of the lower tropospheric and upper tropospheric potential vorticity (PV) was low and quasi-static during the lifecycle of the cyclone Viyaru. For the cyclone Phailin, there was continuous development of the lower tropospheric and upper tropospheric PV, which attained a very high value during its lifecycle. Also there was poor and fluctuating diabatic heating in the middle and upper troposphere and cooling in the lower troposphere for Viyaru. On the contrary, the diabatic heating was positive from lower to upper troposphere with continuous development and increase up to 6◦C in the upper troposphere. -

Shelter and NFI Cluster Evaluation Cyclone Giri Response, Myanmar October 2010 to January 2011 July 2011 Kerren Hedlund

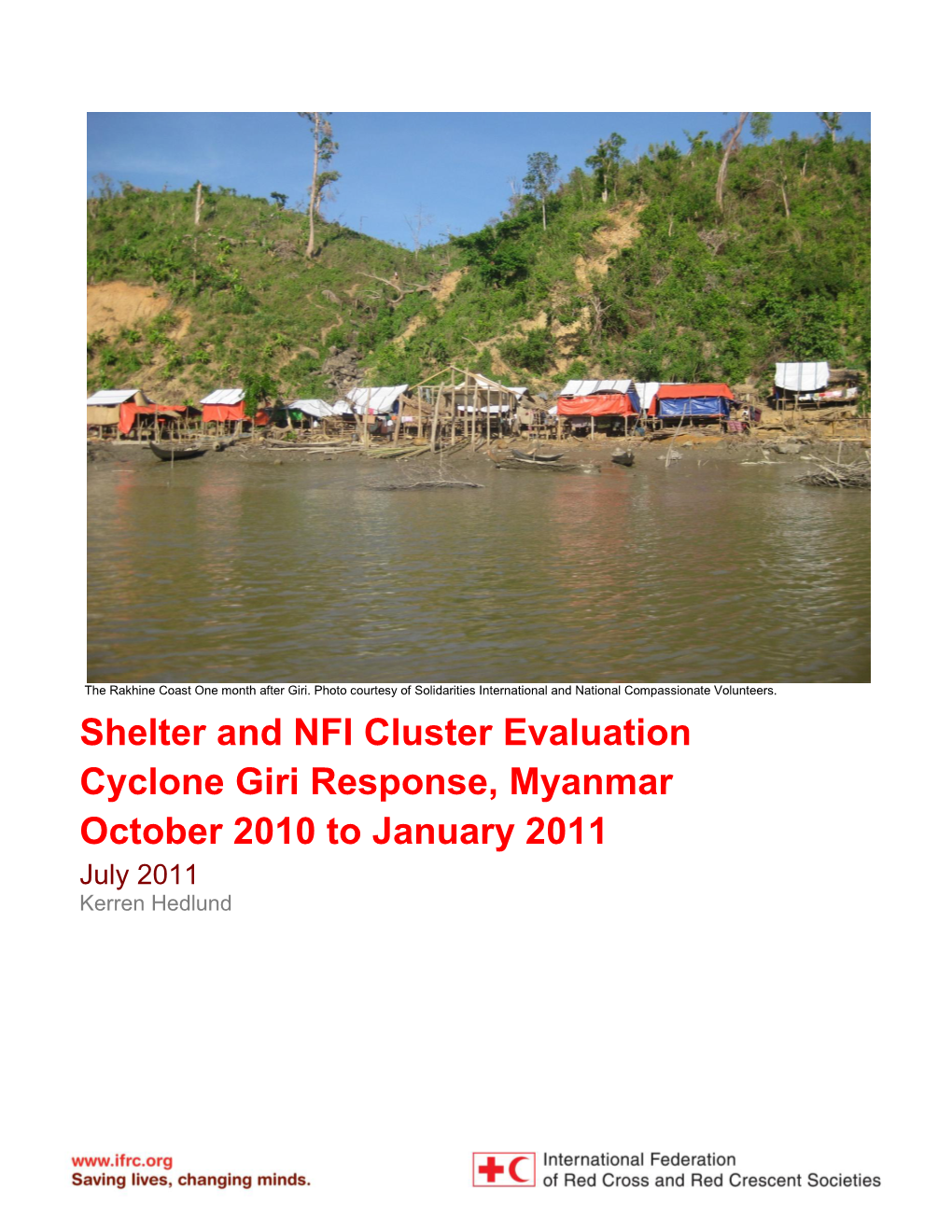

The Rakhine Coast One month after Giri. Photo courtesy of Solidarities International and National Compassionate Volunteers. Shelter and NFI Cluster Evaluation Cyclone Giri Response, Myanmar October 2010 to January 2011 July 2011 Kerren Hedlund This evaluation has been managed by IFRC’s Shelter and Settlements Department in cooperation with the Planning and Evaluation Department. IFRC is committed to upholding its Framework for Evaluation. The framework is designed to promote reliable, useful, ethical evaluations that contribute to organizational learning, accountability, and our mission to best serve those in need. It demonstrates the IFRC’s commitment to transparency, providing a publicly accessible document to all stakeholders so that they may better understand and participate in the evaluation function. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Case postale 372 1211 Genève 19 Suisse Tel: +41 22 730 4222 Fax: +41 22 733 0395 www.ifrc.org Disclaimer The opinions expressed are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect those of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the author(s). Publication of this document does not imply endorsement by the IFRC of the opinions expressed. 2 CONTENT ACRONYMS.......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................ -

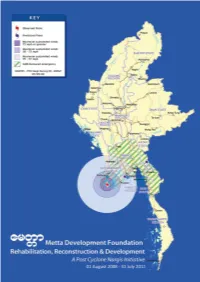

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Meeting Minutes

INFORMAL EMERGENCY SHELTER COORDINATION CYCLONE GIRI MYANMAR MEETING MINUTES Date 26th October, 2010 - 1500-1630hrs Venue Meeting Room, IFRC Office, Yangon Chair Anno Müller Note taker Aung Thu Win (ESC Information Manager ) Ei Ei Thein (MIMU), Myat Su Win (UNOCHA), Aung Ze Ya (MRCS), Nariko Tomiyama (IOM), Nicolas Participants Guillard (ACF), Malar Win (MRCS), Sabine Linzbichler (DRC, Danish Refugee Council), Tin Htut (UNICEF), Maurice (KMSS), Maung Maung Myint (UNHABITAT), Pyae Phyo Aung (IFRC), Maung Maung Than (JICA), Augustine Piary (Karunar Myanmar), Zin Aye Swe (UNHABITAT), Mu Mu Kyi (UNHABITAT), Aaron Brent (French Red Cross), Jero Candela (Solidarites International), Narendra Singh (IFRC), Masayuki Ishikawa (Embassy of Japan), Agenda item # 0: Welcome notes from the Meeting Chair Meeting chair welcomed the participants and introduced himself. He briefly explained the agenda items and requested the involvement and suggestions from all the partners in order to standardize the response. Agenda item # 1: Introduction of Participants - All the participants introduced themselves - Total of 22 participants from 14 different organizations listed below attended the meeting - The Organizations who attended the meeting are, IOM, ACF, MRCS, IFRC, Danish Refugee Council, UNICEF, Karunar Myanmar (KMSS), UNHABITAT, MIMU, UNOCHA, French Red Cross (FRC), JICA, Japanese Embassy, Solidarites International Agenda item # 2: Role definition of informal ESC team Meeting chair convey the offer from IFRC to the partners for independent coordination of the shelter Discussion response with himself as Coordinator and Aung Thu Win as Information Manager. Considering the informal nature of the Emergency Shelter Coordination at this point not all normal tasks can be performed. By example development of an official stra tegy, representation in the media and coordination with authorities will be difficult in the current situation. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2010

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2010 WMO-No. 1074 WMO-No. 1074 © World Meteorological Organization, 2011 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11074-9 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), University of East Anglia, United Kingdom; the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States of America; the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States; the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), United States; the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), United Kingdom; the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), Germany; and the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, United States. -

Myanmar a Country Prone to a Range of Natural Disasters.Pdf

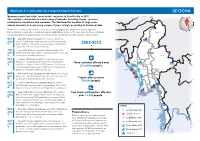

Myanmar: A country prone to a range of natural disasters Myanmar ranks first in the ‘most at risk’ countries in Asia-Pacific in 2011. The country is vulnerable to a wide range of hazards, including floods, cyclones, earthquakes, landslides and tsunamis. The likelihood for medium to large-scale natural disasters to occur every couple of years is high, according to historical data. Whilst these events represented severe losses for the population, hindrances to development interventions, they did also result in increased collaboration between the Government, the international KACHIN community and local organizations, as well as greater preparedness and response interventions. MAY y May 2008 (Cyclone Nargis): The Cyclone Nargis left 2008 some 140,000 people dead and missing in the Ayeyarwady delta region. An estimated 2.4 million people lost partially or 2002-2013 completely, their homes and livelihoods. SAGAING JUN y June 2010 (Floods in northern Rakhine State): The 2010 floods killed 68 people and affected 29,000 families. Over 800 houses were completely destroyed. SHAN OCT y October 2010 (Cyclone Giri): At least 45 people were 2010 killed, over 100,000 people became homeless and some Three cyclones affected over CHIN 260,000 were affected. Over 20,300 houses, 17,500 acres MANDALAY of agricultural land and nearly 50,000 acres of aquaculture 2.6 million people. ponds were damaged by the Cyclone Giri. RAKHINE MAGWAY NAYPYITAW y MAR March 2011 (6.8 Earthquake in Shan State): Over 18,000 KAYAH 2011 people were affected. At least 74 people were killed and 125 BAGO injured. Over 3,000 people became homeless. -

Myanmar Profile

Myanmar Responses to Natural Disasters Presented by Mr. Than Htut Swe, Director Relief and Resettlement Department Republic of Union of Myanmar Myanmar Profile The 2nd largest country in ASEAN with total area of 261,228 sq miles. Neighboring countries: China, Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh, India. More than 100 national races. Population – 59.13 millions 1 Myanmar Hazard Profile Myanmar is prone to Nine Type of Natural Disasters including; *Fire *Forest Fire *Drought *Cyclone *Storm surge *Tsunami *Earthquake *Flood *Landslide Track of Cyclone Nargis Remark: Nargis is the most devastating Disaster Experience to Myanmar 2 THE IMPACTS OF NARGIS SEVERELY AFFECTED 2.4MILLIONS DEATH TOLLS 84,537 MISSING 53,836 SCHOOLS 3,912 HEALTH FACILITIES 630 HOUSE 800,000 TOTAL LOSSES 11.7 TRILLIONS KYATS 3 Track of Cyclone GIRI • Cyclone Giri, a Category Four cyclonic storm, hit Rakhine State on 22 October, 2010. • Kyaukpyu, Sittwe, Myaybon, Ann,Minbya and Pauktaw Townships were the most severely affected areas • Wind speed 120 miles per hour • 35 Dead tolls & 10 missing • Total economic losses was 0.0024 trillion kyats 7 GIRI Cyclone’s Strike 4 Emergency Relief Supplies for the affected Community Emergency Cyclone GIRI Responses by MSWRR No. Vehicle Times Items Tons 1 Myanmar Air Way 1 Foodstuff and Tarpaulin 8 2 Army Air Force 6 36 3 Private Cargo Ship 2 39,45 4 Naval Ship 2 Construction Materials (rods 518 & cement) /Medicine ( By three Land Cruisers) Total 4,507 10 5 Cyclone Hit Victims Reached Under Shelters Within 24 Hours Immediate Repair of -

Higher Education Institutions in MHEW Is Still Low

CABARET BRIEFING PAPER Developing capacity for multi-hazard early warning to improve coastal resilience in Myanmar 1. Summary Myanmar coastal area is exposed to disaster such as cyclone, storm surge, flood and Tsunami. Since Indian Ocean Tsunami (2004) and Cyclone Nargis (2008), people become well aware of natural disaster and pay attention on MHEW. Myanmar is making many efforts to improve MHEW and coastal community resilience in align with global initiative. Regional cooperation works are also found in this context. However, implementation and practicing of existing law and orders are varies based on the local context. Coordination between related ministries is weak. Participation of higher education institutions in MHEW is still low. 2. Policy messages To establish effective MHEW system and coastal community resilience, it is needed: to upgrade hazard forecasting equipment and technology, to upgrade hazard information dissemination channels by using modern technology, to widely give awareness to the public, to reinforce existing infrastructures of coastal area and to establish insurance system and post disaster recovering funding. 3. Introduction Myanmar is high vunerability to natural disasters that results from its unique geographic location and geomorphology. Myanmar boders the Bay of Bengal to the southwest and the Gulf of Martaban and the Andaman Sea along its southern periphery. The country’s extensive coastline of about 1,930 km (1990 mi) and its extensive lowland areas make it particularly vulnerable to all types of marine terrestrial disaster. Department of Hydrology and Meteorology is mainly responsible for gathering of information, analysis and forecasting of hazards for Myanmar. Dissemination of this information to the end user was carried out by General Administration Department through its wide range of network. -

Myanmar• Cyclonic Storm GIRI Situation Report # 2 24 October 2010

Myanmar• Cyclonic Storm GIRI Situation Report # 2 24 October 2010 This report was issued by OCHA Myanmar. It covers the period from 23 to 24 October. The next report will be issued on or around 25 October. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • The Myanmar Meteorology and Hydrology Department reports that the storm has weakened into a tropical depression. Tropical Storm Risk has removed cyclone GIRI from its tracking system since it weakened. • The Myanmar Red Cross Society is conducting assessments in seven affected townships of Rakhine State. Preliminary results in Kyaupyu indicate that at least 4,500 people have been affected, while at least 700 people have been affected in Munaung Township (an island off the coast of Rakhine State). • A donation centre has been established by the Government of the Union of Myanmar at the Fire Service Department in Yangon. Various national NGOs and private donors have already contributed rice and other relief items. II. Situation Overview Situation as at 24 October Cyclone Giri made landfall in Rakhine State on 22 October, close to the town of Kyaukpyu. According to Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) and the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS), the storm had developed into a category 4 cyclone by the time it made landfall, but quickly weakened to category 2 thereafter. The Myanmar Meteorology and Hydrology Department reports on 24 October that the storm has weakened into a tropical depression. Tropical Storm Risk has removed cyclone GIRI from its tracking system since it weakened. Ahead of the cyclone reaching the coast, the Government of the Union of Myanmar had issued warnings to the population living in areas that could be affected by the heavy rains and powerful winds and organized the evacuation of a number of people to higher areas.