Wargames History in and of (Computer) Wargames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Imaginations of Piracy in Video Games

FORUM FOR INTER-AMERICAN RESEARCH (FIAR) VOL. 11.2 (SEP. 2018) 30-43 ISSN: 1867-1519 © forum for inter-american research “In a world without gold, we might have been heroes!” Cultural Imaginations of Piracy in Video Games EUGEN PFISTER (HOCHSCHULE DER KÜNSTE BERN) Abstract From its beginning, colonialism had to be legitimized in Western Europe through cultural and political narratives and imagery, for example in early modern travel reports and engravings. Images and tales of the exotic Caribbean, of beautiful but dangerous „natives“, of unbelievable fortunes and adventures inspired numerous generations of young men to leave for the „new worlds“ and those left behind to support the project. An interesting figure in this set of imaginations in North- Western Europe was the “pirate”: poems, plays, novels and illustrations of dashing young rogues, helping their nation to claim their rightful share of the „Seven Seas“ achieved major successes in France, Britain the Netherlands and beyond. These images – regardless of how far they might have been from their historical inspiration – were immensely successful and are still an integral and popular part of our narrative repertoire: from novels to movies to video games. It is important to note that the “story” was – from the 18th century onwards –almost always the same: a young (often aristocratic) man, unfairly convicted for a crime he didn’t commit became an hors-la-loi against his will but still adhered to his own strict code of conduct and honour. By rescuing a city/ colony/princess he redeemed himself and could be reintegrated into society. Here lies the morale of the story: these imaginations functioned also as acts of political communication, teaching “social discipline”. -

Pegi Annual Report

PEGI ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 2 CHAPTER 1 The PEGI system and how it functions 4 AGE CATEGORIES 5 CONTENT DESCRIPTORS 6 THE PEGI OK LABEL 7 PARENTAL CONTROL SYSTEMS IN GAMING CONSOLES 7 STEPS OF THE RATING PROCESS 9 ARCHIVE LIBRARY 9 CHAPTER 2 The PEGI Organisation 12 THE PEGI STRUCTURE 12 PEGI S.A. 12 BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 12 THE PEGI CONGRESS 12 PEGI MANAGEMENT BOARD 12 PEGI COUNCIL 12 PEGI EXPERTS GROUP 13 COMPLAINTS BOARD 13 COMPLAINTS PROCEDURE 14 THE FOUNDER: ISFE 17 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATOR: NICAM 18 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATOR: VSC 20 PEGI IN THE UK - A CASE STUDY? 21 PEGI CODERS 22 CHAPTER 3 The PEGI Online system 24 CHAPTER 4 PEGI Communication tools and activities 28 Introduction 28 Website 28 Promotional materials 29 Activities per country 29 ANNEX 1 PEGI Code of Conduct 34 ANNEX 2 PEGI Online Safety Code (POSC) 38 ANNEX 3 The PEGI Signatories 44 ANNEX 4 PEGI Assessment Form 50 ANNEX 5 PEGI Complaints 58 1 INTRODUCTION Dear reader, We all know how quickly technology moves on. Yesterday’s marvel is tomorrow’s museum piece. The same applies to games, although it is not just the core game technology that continues to develop at breakneck speed. The human machine interfaces we use to interact with games are becoming more sophisticated and at the same time, easier to use. The Wii Balance Board™ and the MotionPlus™, Microsoft’s Project Natal and Sony’s PlayStation® Eye are all reinventing how we interact with games, and in turn this is playing part in a greater shift. -

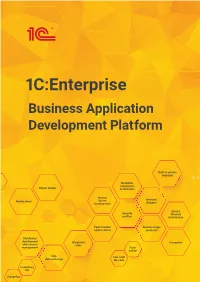

1С:Enterprise HTTP Services Data Processing Model

Application merging In-app messenger with voice and video calls Business Automated components REST API System Flexible analytics log user interface management User settings Data Debugging visualization and performance analytics Seamless Distributed cross-platform Mobile platform databases capability Object-based 1С:Enterprise HTTP services data processing model External Multitenancy data sources Business Application Data access control for individual records JSON Development Platform Thin client Web services Multi-language localization Web client Event alerts Data changelog Git integration Built-in system language Metadata- responsive Report builder architecture Role-based Domain access Interface restrictions Mobile client Driven Development designer HTTP, REST, Intelligent FTP, SMTP, POP3, Auto-generated Service reporting system Security IMAP, OData user interfaces Oriented Cloud profiles Architecture applications Business logic Business composer processes Fault-tolerant Business logic server cluster composer Data Distributed aggregation development Integration Encryption with version tools management Form builder Translation tools Installation XML Low-code Query builder and update data exchange No-code tools In-memory DB Full-text search Changelog Rapid development platform for custom-built business automation solutions Scalable, reliable, efficient, cross-platform, cloud, mobile, desktop 1C:Enterprise is a platform that enables the rapid creation of business automation products. Thousands of off-the-shelf applications have already been developed on the platform. Their functionality can be further customized and expanded using the platform’s development environment. 1C:Enterprise has a low barrier of entry for new developers and lay users thanks to its simple interfaces and visual editing paradigm. Applications developed on the platform easily scale from one to thousands of users and integrate with other 1C and third-party solutions to meet growing business needs. -

Tropico4 Manual.Pdf

Contents Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain Installation & Activation ...................................................................................... 2 visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed Getting Started ....................................................................................................... 3 condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Tropico 4: Gold Edition ......................................................................................... 4 These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered Game Modes ............................................................................................................ 5 vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of Starting a Mission .................................................................................................. 7 consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Interface .................................................................................................................. 11 Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of -

UFO Afterlight

CENEGA PUBLISHING signs new title for 2007 UFO: Afterlight signed for PC-CD ROM March, 1st , 2006 – Prague, Czech Republic CENEGA PUBLISHING has signed a deal with ALTAR Games , founding member of IDEA Games (Independent Developers Association), for another forthcoming PC-CD ROM title from the UFO series, UFO: Afterlight , due to release in Q1 2007. Following the successful UFO: Aftermath and UFO: Aftershock, UFO: Afterlight will improve the current game type and interface and extend the current storyline of the series. CENEGA PUBLISHING and ALTAR Games are looking forward to bring more hours of quality entertainment to UFO fans and all potential players. As its predecessors, UFO: Afterlight is a mixture of squad based tactical action and global strategy with the gamer controlling the actions of elite ground troops, and the running and construction of an intricate network of interlinking bases while collecting resources. UFO: Afterlight takes us to Mars, where a human colony has been built with the help of the Reticulans not long before the events of UFO: Aftershock took place. Mars base is self- sustainable and provides all the necessities for survival of humans on a foreign planet, mainly breathable air, water, food. Although the people inhabiting this colony have the technologies and knowledge required for their further development, basic survival is their major concern. Their only activity is the research of a nearby excavation site, which proves the existence of an ancient intelligent and highly developed alien civilization. The player will enter the game when the research drastically affects all Mars inhabitants. New and unexpected enemies appear in the form of robots, built centuries ago by the unknown aliens for their protection, whose purpose is to eliminate any traces of other civilizations on Mars. -

1C Company Development, Support and Distribution of Software 1C

1C Company Development, support and distribution of software 1C:Enterprise Business applications platform Agenda • About 1C Company and 1C:Enterprise • Ideas of fast implementation for your city • Implementation Results, Examples and Implementation Effects • BI (Business Intelligence) • Regions in which cloud systems are implemented • 1C:FRESH (“cloud” 1C Technology) • 1C Applications: • 1C:Document Management • 1C:Enterprise Accounting, 1C:HR Management • 1C:Small Business 1C:Enterprise Business application platform 1C:Enterprise Integrated solutions for enterprise resource management • Manufacturing management Consolidation CORP • Financial management IFRS finances CRP • Retail management Budgeting Tax accounting PROF Regulated • Warehouse logistics Service Treasury Accounting reporting • CRM CRM Finances Payroll Personnel • HR and Payroll management Retail Clients HR rating, KPI • Financial accounting (1C: Accounting Sales Management Motivation GPS - the most popular accounting app in Logistics Manufacturing PDM GLONASS Business a number of countries) Warehouse Planing processes Maintenance • Docflow management Auto transport Procurement Agreements and repair • Industry solutions WMS Docflow Projects Material and technical Archive supply services ITIL 1С Customers 1С:Enterprise market share in Russia is 83% (in number of workplaces) 1C 83,0% automated workplaces in Russia 1С:Enterprise keys to success • Innovative world-class technological platform • System of platform- based applications for effective management and accounting 1C:Enterprise -

GAMING GLOBAL a Report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with Assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner

GAMING GLOBAL A report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner I Executive Summary The Gaming Global report explores the games environment in: five EU countries, • Finland • France • Germany • Poland • UK three non-EU countries, • Brazil • Russia • Republic of Korea and one non-European region. • East Asia It takes a culturally-focused approach, offers examples of innovative work, and makes the case for British Council’s engagement with the games sector, both as an entertainment and leisure sector, and as a culturally-productive contributor to the arts. What does the international landscape for gaming look like? In economic terms, the international video games market was worth approximately $75.5 billion in 2013, and will grow to almost $103 billion by 2017. In the UK video games are the most valuable purchased entertainment market, outstripping cinema, recorded music and DVDs. UK developers make a significant contribution in many formats and spaces, as do developers across the EU. Beyond the EU, there are established industries in a number of countries (notably Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand) who access international markets, with new entrants such as China and Brazil moving in that direction. Video games are almost always categorised as part of the creative economy, situating them within the scope of investment and promotion by a number of governments. Many countries draw on UK models of policy, although different countries take games either more or less seriously in terms of their cultural significance. The games industry tends to receive innovation funding, with money available through focused programmes. -

Manuel-Tropico-4-Fr.Pdf

A lire avant toute utilisation d’un jeu video par vous-meme ou par votre enfant I. Précautions à prendre dans tous les cas pour l’utilisation d’un jeu vidéo Evitez de jouer si vous êtes fatigué ou si vous manquez de sommeil. Assurez-vous que vous jouez dans une pièce bien éclairée en modérant la luminosité de votre écran. Lorsque vous utilisez un jeu vidéo susceptible d’être connecté à un écran, jouez à bonne distance de cet écran de télévision et aussi loin que le permet le cordon de raccordement. En cours d’utilisation, faites des pauses de dix à quinze minutes toutes les heures. II. Avertissement sur l’épilepsie Certaines personnes sont susceptible de faire des crises d’épilepsie comportant, le cas échéant, des pertes de conscience à la vue, notamment, de certains types de stimulations lumineuses fortes : succession rapide d’images ou répétition de figures géométriques simples, d’éclairs ou d’explosions. Ces personnes s’exposent à des crises lorsqu’elles jouent à certains jeux vidéo comportant de telles stimulations, alors même qu’elles n’ont pas d’antécédent médical ou n’ont jamais été sujettes elles-mêmes à des crises d’épilepsie. Si vous même ou un membre de votre famille avez présenté des symptômes liés à l’épilepsie (crise ou perte de conscience) en présence de stimulations lumineuses, consultez votre médecin avant toute utilisation. Les parents se doivent également d’être particulièrement attentifs à leurs enfants lorsqu’ils jouent avec des jeux vidéo. Si vous-même ou votre enfant présentez un des symptômes suivants : vertige, trouble de la vision, contraction des yeux ou des muscles, trouble de l’orientation, mouvement involontaire ou convulsion, perte momentanée de conscience, il faut cesser immédiatement de jouer et consulter un médecin. -

Playing with People's Lives 1 Playing with People's Lives How City-Builder Games Portray the Public and Their Role in the D

Playing With People’s Lives 1 Playing With People’s Lives How city-builder games portray the public and their role in the decision-making process Senior Honors Thesis, City & Regional Planning Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in City and Regional Planning in the Knowlton School of Architecture at the Ohio State University By William Plumley The Ohio State University May 2018 Faculty Research Mentor: Professor Tijs van Maasakkers, City and Regional Planning Playing With People’s Lives 2 Abstract – City-builder computer games are an integral part of the city planning profession. Educators structure lessons around playtime to introduce planning concepts, professionals use the games as tools of visualization and public outreach, and the software of planners and decision-makers often takes inspiration from the genre. For the public, city-builders are a source of insight into what planners do, and the digital city’s residents show players what role they play in the urban decision-making process. However, criticisms persist through decades of literature from professionals and educators alike but are rarely explored in depth. Published research also ignores the genre’s diverse offerings in favor of focusing on the bestseller of the moment. This project explores how the public is presented in city-builder games, as individuals and as groups, the role the city plays in their lives, and their ability to express their opinions and participate in the process of planning and governance. To more-broadly evaluate the genre as it exists today, two industry-leading titles receiving the greatest attention by planners, SimCity and Cities: Skylines, were matched up with two less-conventional games with their own unique takes on the genre, Tropico 5 and Urban Empire. -

Ssi-96-97Catalog

--· A ' ll:"iDSCAPE C0'1P.\.."'f\ A The Sky Is No Longer Y The Limit. EDlJlE This single or multi-player space strategy game takes you where no gamer has gone before - beyond PANZER GENERAL Volume 4 in the award winning 5-STAR SERIES," STAR GENERAL" boasts an incredibly enhanced PANZER GENERAL game engine. True multiplayer network and modem play. A Two-Level Combat System that accommodates space combat and surface combat. Resource management - conquer enemy planets and develop them for your military needs. Play solo in one huge Fleet Campaign or engage in multi-player scenarios as any of 7 different races. By Catware. ~ DOS CD-ROM, WINDOWS• 9S CD-ROM. Steel PanthersT" Invades The Modem Battlefield! Here's the modem-day version of one of the hottest wargames ever! Set in Europe, Korea and the Middle East from 1950 to 1999, STEEL PANTHERS" II : MODERN BATILES puts you in com mand of a single squad or an entire battalion. Challenge the many historical and hypothetical scenarios - or create your own! Endless custom scenarios can be had using the random scenario generator and powerful scenario editor! And, like its famous predecessor, STEEL PANTHERS II plays like a dream! By Gary Grigsby and Keith Brors. ~ DOS CD-ROM. Retum To A Time When The Rifle Was King. Build armies and participate in the endless battles fought all over the world between 1846-1905. The latest game from Norm Koger, author of TANKS!, AGE OF RIFLES features 8 campaigns and 65 scenarios, including 3 campaigns and 31 scenarios focusing on the American Civil War. -

Gamesretail.Biz, Your Weekly Look at the Key Analysis, News and Data Sources for the Retail Sector, Brought to You by Gamesindustry.Biz and Eurogamer.Net

Brought to you by Every week: The UK games market in less than ten minutes Issue 8: 28th July - 3rd August WELCOME ...to GamesRetail.biz, your weekly look at the key analysis, news and data sources for the retail sector, brought to you by GamesIndustry.biz and Eurogamer.net. THIS WEEK ... we look at how the top publishers have lined up against each other in terms of the traffic they've generated on Eurogamer.net - and how they've done it. Plus, we hear from Ubisoft creative director Michael de Plater, and round up all the week's sales data, need-to-know information, key online prices, jobs and release dates - plus what Eurogamer readers are most looking forward to. Top 3 Publisher Traffic in 2009 ANALYSIS: PUBLISHER SHARE IN 2009 24% A F 22% In this week's analysis we're looking at B G 20% publisher share of traffic to Eurogamer.net and 18% identifying the key drivers. In the first graph is 16% D a comparison over time of the top 3 performers 14% - EA, Activision Blizzard and Capcom. C 12% Point A reflects Capcom's highest traffic 10% E percentage of 2009 to date with a retrospective 8% on the Street Fighter franchise and the review of Percentage of Total Hits on Eurogamer.net 6% Street Fighter IV. Both articles combined in the 4% middle of February, which goes to show the 2% impact a release outside of the normal busy 0% periods can have on generating buzz. Point B Jul Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jan '09 is the Resident Evil IV review, underlining that Capcom Activision Electronic Arts idea further, while Point C demonstrates the interest around Flock! Publisher Share of Eurogamer.net traffic in 2009 12% Points D and E in early May refer to a retrospective on EA's Black and a review of 11% Activision's X-Men Origins: Wolverine 10% respectively, while Point F combines a number 9% of high-ranking articles for EA, including a 8% retrospective on Burnout Paradise and a news 7% story in which Criterion claims that nobody 6% has yet "maxed out" the next-gen consoles. -

1C:Enterprise Platform, New Version 8.3

1C:Enterprise platform, new version 8.3 Innovative, cloud, enterprise-oriented, mobile, cross-platform, and more… The new 1C:Enteprise platform version 8.3 features significant advances in numerous areas. Development of cloud services and Internet-enabled functionality Customer 1 Customer 2 Customer 3 Service vendor Web client Web client Web client Example application: 1C:Accounting Suite Web client Web client Web client Web client Web client Web client Example application: 1C:Small Business Increased scalability and fault tolerance for server clusters and improved load balancing. The new server cluster load balancing architecture provides automatic load balancing between clus- ter nodes based on server availability, fault-tolerance criteria specified by administrators, and real-time server performance analysis. The option to fine-tune the load on specific cluster nodes is available, as well as the option to perform precise management of the memory used by the server processes, which increases the fault tolerance in the event of user mistakes. Automatic monitoring of the cluster state is implemented through the forced shutdown of corrupted processes. Licensing service and external session management service. The licensing service ensures centralized issuing of client and server software licenses, which greatly simplifies server cluster deployments in virtual environments, as well as dynamic changes in resources allocated for specific servers. The external session management service notifies external systems of start session and end session attempts and receives re- sponses that allow or deny these operations. This helps to limit the number of concurrent infobase users, record their total work time, and more. Furthermore, web services are used for interactions with external systems.