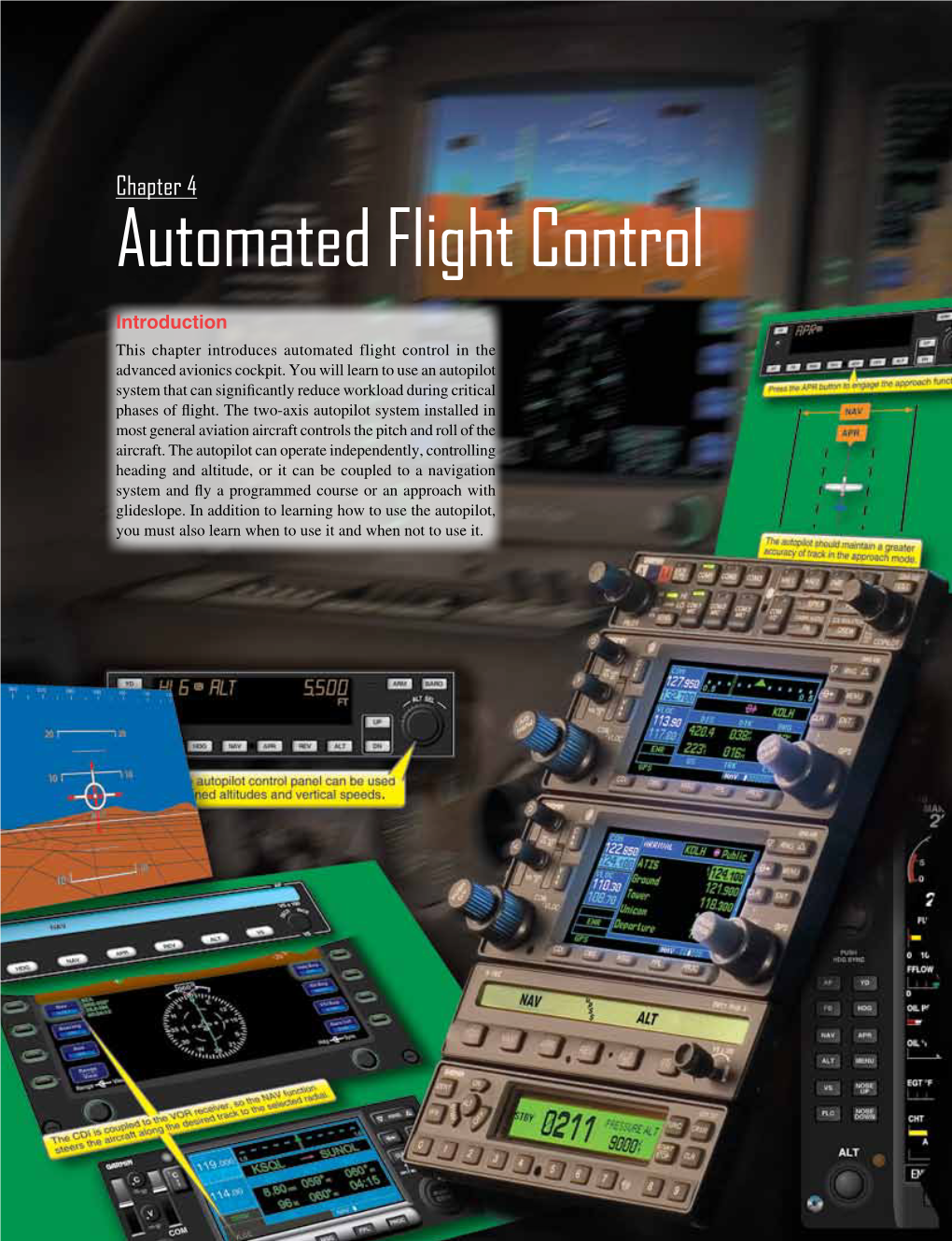

Automated Flight Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pitot-Static System Blockage Effects on Airspeed Indicator

The Dramatic Effects of Pitot-Static System Blockages and Failures by Luiz Roberto Monteiro de Oliveira . Table of Contents I ‐ Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 II ‐ Pitot‐Static Instruments…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 III ‐ Blockage Scenarios – Description……………………………..…………………………………….…..…11 IV ‐ Examples of the Blockage Scenarios…………………..……………………………………………….…15 V ‐ Disclaimer………………………………………………………………………………………………………………50 VI ‐ References…………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……..……51 Please also review and understand the disclaimer found at the end of the article before applying the information contained herein. I - Introduction This article takes a comprehensive look into Pitot-static system blockages and failures. These typically affect the airspeed indicator (ASI), vertical speed indicator (VSI) and altimeter. They can also affect the autopilot auto-throttle and other equipment that relies on airspeed and altitude information. There have been several commercial flights, more recently Air France's flight 447, whose crash could have been due, in part, to Pitot-static system issues and pilot reaction. It is plausible that the pilot at the controls could have become confused with the erroneous instrument readings of the airspeed and have unknowingly flown the aircraft out of control resulting in the crash. The goal of this article is to help remove or reduce, through knowledge, the likelihood of at least this one link in the chain of problems that can lead to accidents. Table 1 below is provided to summarize -

Easy Access Rules for Auxiliary Power Units (CS-APU)

APU - CS Easy Access Rules for Auxiliary Power Units (CS-APU) EASA eRules: aviation rules for the 21st century Rules and regulations are the core of the European Union civil aviation system. The aim of the EASA eRules project is to make them accessible in an efficient and reliable way to stakeholders. EASA eRules will be a comprehensive, single system for the drafting, sharing and storing of rules. It will be the single source for all aviation safety rules applicable to European airspace users. It will offer easy (online) access to all rules and regulations as well as new and innovative applications such as rulemaking process automation, stakeholder consultation, cross-referencing, and comparison with ICAO and third countries’ standards. To achieve these ambitious objectives, the EASA eRules project is structured in ten modules to cover all aviation rules and innovative functionalities. The EASA eRules system is developed and implemented in close cooperation with Member States and aviation industry to ensure that all its capabilities are relevant and effective. Published February 20181 1 The published date represents the date when the consolidated version of the document was generated. Powered by EASA eRules Page 2 of 37| Feb 2018 Easy Access Rules for Auxiliary Power Units Disclaimer (CS-APU) DISCLAIMER This version is issued by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in order to provide its stakeholders with an updated and easy-to-read publication. It has been prepared by putting together the certification specifications with the related acceptable means of compliance. However, this is not an official publication and EASA accepts no liability for damage of any kind resulting from the risks inherent in the use of this document. -

ALT / VS Selector/Alerter

ALT / VS Selector / Alerter PN 01279-( ) Pilot’s Operating Handbook ENT ALT SEL ALR DH VS BARO S–TEC * Asterisk indicates pages changed, added, or deleted by List of Effective Pages current revision. Retain this record in front of handbook. Upon receipt of a Record of Revisions revision, insert changes and complete table below. Revision Number Revision Date Insertion Date/Initials 1st Ed. Oct 26, 00 2nd Ed. Jan 15, 08 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 i S–TEC Page Intentionally Blank ii 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 S–TEC Table of Contents Sec. Pg. 1 Overview...........................................................................................................1–1 1.1 Document Organization....................................................................1–3 1.2 Purpose..............................................................................................1–3 1.3 General Control Theory....................................................................1–3 1.4 Block Diagram....................................................................................1–4 2 Pre-Flight Procedures...................................................................................2–1 2.1 Pre-Flight Test....................................................................................2–3 3 In-Flight Procedures......................................................................................3–1 3.1 Selector / Alerter Operation..............................................................3–3 3.1.1 Data Entry.............................................................................3–3 -

Exec Summary (PDF)

BEECHCRAFT® AT-6 The Future of Light Attack is Here. Capable. Affordable. Sustainable. Interoperable. One platform with multiple missions: initial pilot training, weapons training, operational NetCentric ISR and Light Attack capabilities for irregular warfare. The Beechcraft AT-6 is a multi-role, multi-mission aircraft system designed to meet a wide spectrum of warfighter needs: • Based on the proven Beechcraft USAF T-6A and USN T-6B • Designed to accommodate 95% of the aircrew population; widest range in its class • Lockheed Martin plug-and-play mission system architecture adapted from A-10C • Sensor suite adapted from the MC-12W • Flexible, reconfigurable hardpoints with six external store stations Unparalleled attributes with • Long persistence with two aircrew and weapons; up to 1,485 nm self-deployment range a wide range of options. • Extensive variety of weapons including general purpose, laser guided and inertially-aided munitions AIRFRAME AND POWERPLANT • 1,600 shaft horsepower engine • The only fixed-wing aircraft to fire laser guided rockets • ISR suite and six external store hardpoints • Light armor COMBAT MISSION SYSTEMS • Mission systems by Lockheed Martin • NVIS cockpit • Helmet-mounted cueing system • Infrared missile warning and countermeasures COMMUNICATIONS SUITE • Secure voice and data • Rover-compatible full motion video • SADL/Link-16 compatible • SATCOM ISR SUITE • MX-15Di WEAPONS INTEGRATION • 17 60 capable stores management system • .50 Cal Gun • 20mm Gun • 250/500 lb. laser guided GPS or GP bombs • Laser guided missiles • Laser guided rockets • Small 1760 weapons Learn more. Call +1.316.676.0800 or visit Beechcraft.com 13LSAT6HW Specifications and performance are subject to change without notice. -

How Doc Draper Became the Father of Inertial Guidance

(Preprint) AAS 18-121 HOW DOC DRAPER BECAME THE FATHER OF INERTIAL GUIDANCE Philip D. Hattis* With Missouri roots, a Stanford Psychology degree, and a variety of MIT de- grees, Charles Stark “Doc” Draper formulated the basis for reliable and accurate gyro-based sensing technology that enabled the first and many subsequent iner- tial navigation systems. Working with colleagues and students, he created an Instrumentation Laboratory that developed bombsights that changed the balance of World War II in the Pacific. His engineering teams then went on to develop ever smaller and more accurate inertial navigation for aircraft, submarines, stra- tegic missiles, and spaceflight. The resulting inertial navigation systems enable national security, took humans to the Moon, and continue to find new applica- tions. This paper discusses the history of Draper’s path to becoming known as the “Father of Inertial Guidance.” FROM DRAPER’S MISSOURI ROOTS TO MIT ENGINEERING Charles Stark Draper was born in 1901 in Windsor Missouri. His father was a dentist and his mother (nee Stark) was a school teacher. The Stark family developed the Stark apple that was popular in the Midwest and raised the family to prominence1 including a cousin, Lloyd Stark, who became governor of Missouri in 1937. Draper was known to his family and friends as Stark (Figure 1), and later in life was known by colleagues as Doc. During his teenage years, Draper enjoyed tinkering with automobiles. He also worked as an electric linesman (Figure 2), and at age 15 began a liberal arts education at the University of Mis- souri in Rolla. -

E6bmanual2016.Pdf

® Electronic Flight Computer SPORTY’S E6B ELECTRONIC FLIGHT COMPUTER Sporty’s E6B Flight Computer is designed to perform 24 aviation functions and 20 standard conversions, and includes timer and clock functions. We hope that you enjoy your E6B Flight Computer. Its use has been made easy through direct path menu selection and calculation prompting. As you will soon learn, Sporty’s E6B is one of the most useful and versatile of all aviation computers. Copyright © 2016 by Sportsman’s Market, Inc. Version 13.16A page: 1 CONTENTS BEFORE USING YOUR E6B ...................................................... 3 DISPLAY SCREEN .................................................................... 4 PROMPTS AND LABELS ........................................................... 5 SPECIAL FUNCTION KEYS ....................................................... 7 FUNCTION MENU KEYS ........................................................... 8 ARITHMETIC FUNCTIONS ........................................................ 9 AVIATION FUNCTIONS ............................................................. 9 CONVERSIONS ....................................................................... 10 CLOCK FUNCTION .................................................................. 12 ADDING AND SUBTRACTING TIME ....................................... 13 TIMER FUNCTION ................................................................... 14 HEADING AND GROUND SPEED ........................................... 15 PRESSURE AND DENSITY ALTITUDE ................................... -

Beforethe Runway

EDITORIAL Before the runway By Professor Sidney dekker display with fl ight information. My airspeed is leaking out of Editors Note: This time, we decided to invite some the airplane as if the hull has been punctured, slowly defl at- comments on Professor Dekker’s article from subject ing like a pricked balloon. It looks bizarre and scary and the matter experts. Their responses follow the article. split second seems to last for an eternity. Yet I have taught myself to act fi rst and question later in situations like this. e are at 2,000 feet, on approach to the airport. The big So I act. After all, there is not a whole lot of air between me W jet is on autopilot, docile, and responsively follow- and the hard ground. I switch off the autothrottle and shove ing the instructions I have put into the various computer the thrust levers forward. From behind, I hear the engines systems. It follows the heading I gave it, and stays at the screech, shrill and piercing. Airspeed picks up. I switch off altitude I wanted it at. The weather is alright, but not great. the autopilot for good measure (or good riddance) and fl y Cloud base is around 1000 feet, there is mist, a cold driz- the jet down to the runway. It feels solid in my hands and zle. We should be on the ground in the next few minutes. docile again. We land. Then everything comes to a sudden I call for fl aps, and the other pilot selects them for me. -

PC-6/B2-H4 Airplane Flight Manual Doc. No. 1820 at Revision 8

PILOT’S INFORMATION MANUAL PC-6/B2-H4 applicable from AC S/N 825 PILOT’S INFORMATION MANUAL PC-6/B2-H4 applicable from AC S/N 825 WARNING •This PC-6 Pilot’s Information Manual is published for general and familiarization purposes only. •This Pilot’s Information Manual does NOT meet FAA, FOCA or any other civil aviation authority regulations for operation of ANY Aircraft. •This Pilot’s Information Manual is a reproduction of a PC-6 Airplane Flight Manual, however, it is NOT revised or updated. •This Pilot’s Information Manual does NOT reflect the configuration or operating parameters of any actual aircraft. •Only the Approved Airplane Flight Manual issued for a specific serial number aircraft may be used for actual operation of that serial number aircraft. Pilatus Aircraft Ltd P.O. Box 992 6371 Stans, Switzerland Phone +41 41 619 67 00 Fax +41 41 619 92 00 [email protected] www.pilatus-aircraft.com AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL PC-6/B2-H4 ONLY REPORT NO. 1820 PURPOSES REGISTRATION ._____ __. SERIAL NO . APPLICABLE FROM A/C SIN 825 FAMILIARIZATION THIS AIRPLANDANE IS TO BE OPERAT ED IN COMPLIANCE WITH INFORMATION AND LIMI TATIONS CONTAINED HEREIN THIS FLIGHT MANUAL IS TO BE KEPT GENERAL IN THE AIRCRAFT AT ALL TIMES FOR Approved by: SWISS FEDERAL OFF FOR CIVIL AVIATION · �L Nov 20, JS�S" Date of Approval : ____·- ______ PILATUS AIRCRAFT LTD STANS/SWITZERLAND ONLY PURPOSES FAMILIARIZATION AND GENERAL FOR © Pilatus Aircraft Ltd. This document contains proprietary information that is protected by copyright. All rights are reserved, No part of this document may be copied, reproduced or translated to other languages without the prior written consent of Pilatus Aircraft Ltd. -

Development and Flight Test Experiences with a Flight-Crucial Digital Control System

NASA Technical Paper 2857 1 1988 Development and Flight Test Experiences With a Flight-Crucial Digital Control System Dale A. Mackall Ames Research Center Dryden Flight Research Facility Edwards, Calgornia I National Aeronautics I and Space Administration I Scientific and Technical Information Division I CONTENTS Page ~ SUMMARY ................................... 1 I 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 2 NOMENCLATURE . 2 3 SYSTEM SPECIFICATION . 5 3.1 Control Laws and Handling Qualities ................. 5 3.2 Reliability and Fault Tolerance ................... 5 4 DESIGN .................................. 6 4.1 System Architecture and Fault Tolerance ............... 6 4.1.1 Digital flight control system architecture .......... 6 4.1.2 Digital flight control system computer hardware ........ 8 4.1.3 Avionics interface ...................... 8 4.1.4 Pilot interface ........................ 9 4.1.5 Actuator interface ...................... 10 4.1.6 Electrical system interface .................. 11 4.1.7 Selector monitor and failure manager ............. 12 4.1.8 Built-in test and memory mode ................. 14 4.2 ControlLaws ............................. 15 4.2.1 Control law development process ................ 15 4.2.2 Control law design ...................... 15 4.3 Digital Flight Control System Software ................ 17 4.3.1 Software development process ................. 18 4.3.2 Software design ........................ 19 5 SYSTEM-SOFTWARE QUALIFICATION AND DESIGN ITERATIONS ............ 19 5.1 Schedule ............................... 20 5.2 Software Verification ........................ 21 5.2.1 Verification test plan .................... 21 5.2.2 Verification support equipment . ................ 22 5.2.3 Verification tests ...................... 22 5.2.4 Reverifying the design iterations ............... 24 5.3 System Validation .......................... 24 5.3.1 Validation test plan . ............... 24 5.3.2 Support equipment ....................... 25 5.3.3 Validation tests ....................... 25 5.3.4 Revalidation of designs ................... -

RNAV Instrument Approach Procedures (IAP's) and the New Charting Format

Effective: Until Further Notice Area Navigation Systems Area Navigation (RNAV)/Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) Instrument Approach Procedures (IAP’s) and the New Charting Format. [REVISED 1/5/00] PURPOSE. Instrument procedures in the first half of the 21st century will be based on satellite navigation, also known as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). Within the United States, the Global Positioning System (GPS), the Wide Area Augmentation system (WAAS), and the Local Area Augmentation System (LAAS) will comprise the primary components of the GNSS. Air navigation is increasingly dependent upon RNAV systems - as exemplified by Flight Management System (FMS) and Global Positioning System (GPS) avionics. These systems navigate with reference to geographic positions called “waypoints” (WP) specified in latitude/longitude rather than to/from a specific ground-based navigation aid. Reliance on RNAV systems for approach and departure operations will increase as new systems such as WAAS are developed and deployed. To foster and support full and optimal integration of RNAV into the National Airspace System (NAS), the FAA has developed a new procedure type for RNAV IAP’s. This Notice serves to inform the flying public of the new concepts being implemented with the RNAV IAP’s. OPERATIONS. In order to avoid unnecessary duplication and proliferation of instrument approach charts, Jeppesen will publish approach minimums for unaugmented GPS and WAAS (when operational) on the same chart. In addition, approach minimums will be established and published for LNAV/ VNAV - a new type of RNAV instrument approach with lateral and vertical navigation. The approach chart will be titled "RNAV RWY XX." The chart may contain as many as four columns of approach minimums: GLS; LNAV/VNAV; LNAV; and CIRCLING. -

The Difference Between Higher and Lower Flap Setting Configurations May Seem Small, but at Today's Fuel Prices the Savings Can Be Substantial

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HIGHER AND LOWER FLAP SETTING CONFIGURATIONS MAY SEEM SMALL, BUT AT TODAY'S FUEL PRICES THE SAVINGS CAN BE SUBSTANTIAL. 24 AERO QUARTERLY QTR_04 | 08 Fuel Conservation Strategies: Takeoff and Climb By William Roberson, Senior Safety Pilot, Flight Operations; and James A. Johns, Flight Operations Engineer, Flight Operations Engineering This article is the third in a series exploring fuel conservation strategies. Every takeoff is an opportunity to save fuel. If each takeoff and climb is performed efficiently, an airline can realize significant savings over time. But what constitutes an efficient takeoff? How should a climb be executed for maximum fuel savings? The most efficient flights actually begin long before the airplane is cleared for takeoff. This article discusses strategies for fuel savings But times have clearly changed. Jet fuel prices fuel burn from brake release to a pressure altitude during the takeoff and climb phases of flight. have increased over five times from 1990 to 2008. of 10,000 feet (3,048 meters), assuming an accel Subse quent articles in this series will deal with At this time, fuel is about 40 percent of a typical eration altitude of 3,000 feet (914 meters) above the descent, approach, and landing phases of airline’s total operating cost. As a result, airlines ground level (AGL). In all cases, however, the flap flight, as well as auxiliarypowerunit usage are reviewing all phases of flight to determine how setting must be appropriate for the situation to strategies. The first article in this series, “Cost fuel burn savings can be gained in each phase ensure airplane safety. -

Inflight Data Collection N75-14745 Fob Ride Quality

NASA CR-127492 INFLIGHT DATA COLLECTION FOR RIDE QUALITY AND ATMOSPHERIC TURBULENCE RESEARCH Paul W. Kadlec and Roger G. Buckman Continental Air Lines, Inc. Los Angeles, California 90009 (NASA-CR-127492) INFLIGHT DATA COLLECTION N75-14745 FOB RIDE QUALITY AND ATMOSPHERIC TURBULENCE RESEARCH Final Report (Continental Airlines, Inc.) 57 p HC $4.25 CSCL 01C Unclas ..- - ___G3/0 5 05079 December 1974 Prepared for NASA FLIGHT RESEARCH CENTER P.O. Box 273 Edwards, California 93523 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. NASA CR-127492 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date INFLIGHT DATA COLLECTION FOR RIDE QUALITY AND December 1974 ATMOSPHERIC TURBULENCE RESEARCH 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Paul W. Kadlec and Roger G. Buckman 10. Work Unit No. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 504-29-21 Continental Air Lines, Inc. 11. Contract or Grant No. Los Angeles, California 90009 NAS 4-1982 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Contractor Report - Final National Aeronautics and Space Administration 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, D. C., 20546 H-876 15. Supplementary Notes NASA Technical Monitor: Shu W. Gee 16. Abstract In 1971 Continental Air Lines and the National Center for Atmospheric Research originated a joint program to study the genesis and nature of clear air turbulence. With the support of the NASA Flight Research Center, the program was expanded to include an investigation of the effects of atmospheric turbu- lence on passenger ride quality in a large wide-body commercial aircraft.