Basic Principles of Inertial Navigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wireless Accelerometer - G-Force Max & Avg

The Leader in Low-Cost, Remote Monitoring Solutions Wireless Accelerometer - G-Force Max & Avg General Description Monnit Sensor Core Specifications The RF Wireless Accelerometer is a digital, low power, • Wireless Range: 250 - 300 ft. (non line-of-sight / low profile, capacitive sensor that is able to measure indoors through walls, ceilings & floors) * acceleration on three axes. Four different • Communication: RF 900, 920, 868 and 433 MHz accelerometer types are available from Monnit. • Power: Replaceable batteries (optimized for long battery life - Line-power (AA version) and solar Free iMonnit basic online wireless (Industrial version) options available sensor monitoring and notification • Battery Life (at 1 hour heartbeat setting): ** system to configure sensors, view data AA battery > 4-8 years and set alerts via SMS text and email. Coin Cell > 2-3 years. Industrial > 4-8 years Principle of Operation * Actual range may vary depending on environment. ** Battery life is determined by sensor reporting Accelerometer samples at 800 Hz over a 10 second frequency and other variables. period, and reports the measured MAXIMUM value for each axis in g-force and the AVERAGE measured g-force on each axis over the same period, for all three axes. (Only available in the AA version.) This sensor reports in every 10 seconds with this data. Other sampling periods can be configured, down to one second and up to 10 minutes*. The data reported is useful for tracking periodic motion. Sensor data is displayed as max and average. Example: • Max X: 0.125 Max Y: 1.012 Max Z: 0.015 • Avg X: 0.110 Avg Y: 1.005 Avg Z: 0.007 * Customer cannot configure sampling period on their own. -

Measurement of the Earth Tides with a MEMS Gravimeter

1 Measurement of the Earth tides with a MEMS gravimeter ∗ y ∗ y ∗ ∗ ∗ 2 R. P. Middlemiss, A. Samarelli, D. J. Paul, J. Hough, S. Rowan and G. D. Hammond 3 The ability to measure tiny variations in the local gravitational acceleration allows { amongst 4 other applications { the detection of hidden hydrocarbon reserves, magma build-up before volcanic 5 eruptions, and subterranean tunnels. Several technologies are available that achieve the sensi- p 1 6 tivities required for such applications (tens of µGal= Hz): free-fall gravimeters , spring-based 2; 3 4 5 7 gravimeters , superconducting gravimeters , and atom interferometers . All of these devices can 6 8 observe the Earth Tides ; the elastic deformation of the Earth's crust as a result of tidal forces. 9 This is a universally predictable gravitational signal that requires both high sensitivity and high 10 stability over timescales of several days to measure. All present gravimeters, however, have limita- 11 tions of excessive cost (> $100 k) and high mass (>8 kg). We have built a microelectromechanical p 12 system (MEMS) gravimeter with a sensitivity of 40 µGal= Hz in a package size of only a few 13 cubic centimetres. We demonstrate the remarkable stability and sensitivity of our device with a 14 measurement of the Earth tides. Such a measurement has never been undertaken with a MEMS 15 device, and proves the long term stability of our instrument compared to any other MEMS device, 16 making it the first MEMS accelerometer to transition from seismometer to gravimeter. This heralds 17 a transformative step in MEMS accelerometer technology. -

A GUIDE to USING FETS for SENSOR APPLICATIONS by Ron Quan

Three Decades of Quality Through Innovation A GUIDE TO USING FETS FOR SENSOR APPLICATIONS By Ron Quan Linear Integrated Systems • 4042 Clipper Court • Fremont, CA 94538 • Tel: 510 490-9160 • Fax: 510 353-0261 • Email: [email protected] A GUIDE TO USING FETS FOR SENSOR APPLICATIONS many discrete FETs have input capacitances of less than 5 pF. Also, there are few low noise FET input op amps Linear Systems that have equivalent input noise voltages density of less provides a variety of FETs (Field Effect Transistors) than 4 nV/ 퐻푧. However, there are a number of suitable for use in low noise amplifier applications for discrete FETs rated at ≤ 2 nV/ 퐻푧 in terms of equivalent photo diodes, accelerometers, transducers, and other Input noise voltage density. types of sensors. For those op amps that are rated as low noise, normally In particular, low noise JFETs exhibit low input gate the input stages use bipolar transistors that generate currents that are desirable when working with high much greater noise currents at the input terminals than impedance devices at the input or with high value FETs. These noise currents flowing into high impedances feedback resistors (e.g., ≥1MΩ). Operational amplifiers form added (random) noise voltages that are often (op amps) with bipolar transistor input stages have much greater than the equivalent input noise. much higher input noise currents than FETs. One advantage of using discrete FETs is that an op amp In general, many op amps have a combination of higher that is not rated as low noise in terms of input current noise and input capacitance when compared to some can be converted into an amplifier with low input discrete FETs. -

Development and Flight Test Experiences with a Flight-Crucial Digital Control System

NASA Technical Paper 2857 1 1988 Development and Flight Test Experiences With a Flight-Crucial Digital Control System Dale A. Mackall Ames Research Center Dryden Flight Research Facility Edwards, Calgornia I National Aeronautics I and Space Administration I Scientific and Technical Information Division I CONTENTS Page ~ SUMMARY ................................... 1 I 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 2 NOMENCLATURE . 2 3 SYSTEM SPECIFICATION . 5 3.1 Control Laws and Handling Qualities ................. 5 3.2 Reliability and Fault Tolerance ................... 5 4 DESIGN .................................. 6 4.1 System Architecture and Fault Tolerance ............... 6 4.1.1 Digital flight control system architecture .......... 6 4.1.2 Digital flight control system computer hardware ........ 8 4.1.3 Avionics interface ...................... 8 4.1.4 Pilot interface ........................ 9 4.1.5 Actuator interface ...................... 10 4.1.6 Electrical system interface .................. 11 4.1.7 Selector monitor and failure manager ............. 12 4.1.8 Built-in test and memory mode ................. 14 4.2 ControlLaws ............................. 15 4.2.1 Control law development process ................ 15 4.2.2 Control law design ...................... 15 4.3 Digital Flight Control System Software ................ 17 4.3.1 Software development process ................. 18 4.3.2 Software design ........................ 19 5 SYSTEM-SOFTWARE QUALIFICATION AND DESIGN ITERATIONS ............ 19 5.1 Schedule ............................... 20 5.2 Software Verification ........................ 21 5.2.1 Verification test plan .................... 21 5.2.2 Verification support equipment . ................ 22 5.2.3 Verification tests ...................... 22 5.2.4 Reverifying the design iterations ............... 24 5.3 System Validation .......................... 24 5.3.1 Validation test plan . ............... 24 5.3.2 Support equipment ....................... 25 5.3.3 Validation tests ....................... 25 5.3.4 Revalidation of designs ................... -

Utilising Accelerometer and Gyroscope in Smartphone to Detect Incidents on a Test Track for Cars

Utilising accelerometer and gyroscope in smartphone to detect incidents on a test track for cars Carl-Johan Holst Data- och systemvetenskap, kandidat 2017 Luleå tekniska universitet Institutionen för system- och rymdteknik LULEÅ UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY BACHELOR THESIS Utilising accelerometer and gyroscope in smartphone to detect incidents on a test track for cars Author: Examiner: Carl-Johan HOLST Patrik HOLMLUND [email protected] [email protected] Supervisor: Jörgen STENBERG-ÖFJÄLL [email protected] Computer and space technology Campus Skellefteå June 4, 2017 ii Abstract Utilising accelerometer and gyroscope in smartphone to detect incidents on a test track for cars Every smartphone today includes an accelerometer. An accelerometer works by de- tecting acceleration affecting the device, meaning it can be used to identify incidents such as collisions at a relatively high speed where large spikes of acceleration often occur. A gyroscope on the other hand is not as common as the accelerometer but it does exists in most newer phones. Gyroscopes can detect rotations around an arbitrary axis and as such can be used to detect critical rotations. This thesis work will present an algorithm for utilising the accelerometer and gy- roscope in a smartphone to detect incidents occurring on a test track for cars. Sammanfattning Utilising accelerometer and gyroscope in smartphone to detect incidents on a test track for cars Alla smarta telefoner innehåller idag en accelerometer. En accelerometer analyserar acceleration som påverkar enheten, vilket innebär att den kan användas för att de- tektera incidenter så som kollisioner vid relativt höga hastigheter där stora spikar av acceleration vanligtvis påträffas. -

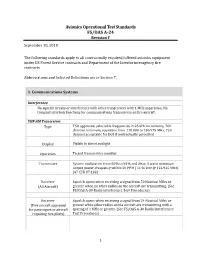

FS/OAS A-24, Avionics Operational Test Standards for Contractually

Avionics Operational Test Standards FS/OAS A-24 Revision F September 10, 2018 The following standards apply to all contractually required/offered avionics equipment under US Forest Service contracts and Department of the Interior interagency fire contracts. Abbreviations and Selected Definitions are in Section 7. 1. Communications Systems Interference No squelch breaks or interference with other transceivers with 1 MHz separation. No transmit interlock functions for communications transceivers on fire aircraft. VHF-AM Transceiver Type TSO approved, selectable frequencies in 25 kHz increments, 760 channel minimum, operation from 118.000 to 136.975 MHz, 720 channel acceptable for DOI if contractually permitted Display Visible in direct sunlight Operation To and from service monitor Transmitter System modulation from 50% to 95% and clear, 5 watts minimum output power, frequency within 20 PPM (+2.46 kHz @ 122.925 MHz) (47 CFR 87.133) Receiver Squelch opens when receiving a signal from 50 Nautical Miles or (All Aircraft) greater when no other radios on the aircraft are transmitting. (See FS/OAS A-30 Radio Interference Test Procedures) Receiver Squelch opens when receiving a signal from 24 Nautical Miles or (Fire aircraft approved greater while other radios on the aircraft are transmitting with a for passengers or aircraft spacing of 2 MHz or greater. (See FS/OAS A-30 Radio Interference requiring two pilots) Test Procedures) 1 Aeronautical VHF-FM Transceiver (P25 required for Fire) Type Listed on Approved Radios list, P25 meets FS/AMD A-19 -

Radar Altimeter True Altitude

RADAR ALTIMETER TRUE ALTITUDE. TRUE SAFETY. ROBUST AND RELIABLE IN RADARDEMANDING ENVIRONMENTS. Building on systems engineering and integration know-how, FreeFlight Systems effectively implements comprehensive, high-integrity avionics solutions. We are focused on the practical application of NextGen technology to real-world operational needs — OEM, retrofit, platform or infrastructure. FreeFlight Systems is a community of respected innovators in technologies of positioning, state-sensing, air traffic management datalinks — including rule-compliant ADS-B systems, data and flight management. An international brand, FreeFlight Systems is a trusted partner as well as a direct-source provider through an established network of relationships. 3 GENERATIONS OF EXPERIENCE BEHIND NEXTGEN AVIONICS NEXTGEN LEADER. INDUSTRY EXPERT. TRUSTED PARTNER. SHAPE THE SKIES. RADAR ALTIMETERS FreeFlight Systems’ certified radar altimeters work consistently in the harshest environments including rotorcraft low altitude hover and terrain transitions. RADAROur radar altimeter systems integrate with popular compatible glass displays. AL RA-4000/4500 & FreeFlight Systems modern radar altimeters are backed by more than 50 years of experience, and FRA-5500 RADAR ALTIMETERS have a proven track record as a reliable solution in Model RA-4000 RA-4500 FRA-5500 the most challenging and critical segments of flight. The TSO and ETSO-approved systems are extensively TSO-C87 l l l deployed worldwide in helicopter fleets, including ETSO-2C87 l l l some of the largest HEMS operations worldwide. DO-160E l l l DO-178 Level B l Designed for helicopter and seaplane operations, our DO-178B Level C l l radar altimeters provide precise AGL information from 2,500 feet to ground level. -

Full Auto-Calibration of a Smartphone on Board a Vehicle Using IMU and GPS Embedded Sensors

Full auto-calibration of a smartphone on board a vehicle using IMU and GPS embedded sensors Javier Almaz´an, Luis M. Bergasa, J. Javier Yebes, Rafael Barea and Roberto Arroyo Abstract| Nowadays, smartphones are widely used Smartphones provide two kinds of measurements. The in the world, and generally, they are equipped with first ones are relative to the world, such as GPS and many sensors. In this paper we study how powerful magnetometers. The second ones are relative to the the low-cost embedded IMU and GPS could become for Intelligent Vehicles. The information given by device, such as accelerometers and gyroscopes. Knowing accelerometer and gyroscope is useful if the relations the relation between the smartphone reference system between the smartphone reference system, the vehicle and the world reference system is very important in order reference system and the world reference system are to reference the second kind of measurements globally [3]. known. Commonly, the magnetometer sensor is used In other words, working with this kind of measurements to determine the orientation of the smartphone, but its main drawback is the high influence of electro- involves knowing the pose of the smartphone in the magnetic interference. In view of this, we propose a world. novel automatic method to calibrate a smartphone Intelligent Vehicles can be helped by using in-vehicle on board a vehicle using its embedded IMU and smartphones to measure some driving indicators. On the GPS, based on longitudinal vehicle acceleration. To one hand, using smartphones requires no extra hardware the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to estimate the yaw angle of a smartphone relative to a mounted in the vehicle, offering cheap and standard vehicle in every case, even on non-zero slope roads. -

Influence of Coupled Sidesticks on the Pilot Monitoring's Awareness

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institute of Transport Research:Publications Influence of Coupled Sidesticks on the Pilot Monitoring's Awareness During Flare Alan F. Uehara∗ and Dominik Niedermeiery DLR (German Aerospace Center), Braunschweig, Germany, 38108 Passive sidesticks have been used in modern fly-by-wire commercial airplanes since the late 1980s. These passive sidesticks typically do not feature a mechanical coupling between them, so the pilot's and copilot's sidesticks move independently. This characteristic disabled the pilot monitoring (PM) to perceive the control inputs of the pilot flying (PF). This can lead to problems of awareness in abnormal situations. The development of active inceptor technology made it possible to electronically couple two sidesticks emulating a mechanical coupling. This research focuses on the benefits of coupled sidesticks to the situation awareness of the PM. The final approach and landing scenario was considered for this study. Twelve pilots participated in the simulator experiment. Results suggest that the coupling between sidesticks, allowing the PM to perceive the PF's inputs, can improve the PM's situation awareness. Nomenclature ADI Attitude Director Indicator PF Pilot Flying AGL Above Ground Level PFD Primary Flight Display ATC Air Traffic Control PM Pilot Monitoring DLR German Aerospace Center PNF Pilot Not Flying FAA Federal Aviation Administration SA Situation Awareness FBW Fly-By-Wire SOP Standard Operating Procedure FCS Flight Control System TOGA Takeoff/Go-Around KCAS Knots Calibrated Airspeed VMC Visual Meteorological Conditions IMC Instrument Meteorological Conditions I. Introduction he control inceptors and the actuators of the control surfaces are mechanically decoupled in fly-by-wire T(FBW) airplanes. -

Fly-By-Wire: Getting Started on the Right Foot and Staying There…

Fly-by-Wire: Getting started on the right foot and staying there… Imagine yourself getting into the cockpit of an aircraft, finishing your preflight checks, and taxiing out to the runway ready for takeoff. You begin the takeoff roll and start to rotate. As you lift off, you discover your side stick controller is not responding correctly to your commands. Panic sets in, and you feel that you’ve lost total control of the aircraft. Thanks to quick action from your second in command, he takes over and stabilizes the aircraft so that you both can plan to return to the airport under reversionary mode. This situation could have been a catastrophe. This happened in August of 2001. A Lufthansa Airbus A320 came within less than two feet and a few seconds of crashing during takeoff on a planned flight from Frankfurt to Paris. Preliminary reports indicated that maintenance was performed on the captain’s sidestick controller immediately before the incident. This had inadvertently created a situation in which control inputs were reversed. The case reveals that at least two "filters," or safety defenses, were breached, leading to a near-crash shortly after rotation at Frankfurt’s Runway 18. Quick action by the first officer prevented a catastrophe. Lufthansa Technik personnel found a damaged pin on one segment of the four connector segments (with 140 pins on each) at the "rack side," as it were, of the avionics mount. This incident prompted an article to be published in the 2003 November-December issue of the Flight Safety Mechanics Bulletin. The report detailed all that transpired during the maintenance and subsequent release of the aircraft. -

Accelerometers

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY,PHYSICSAND ASTRONOMY AS.173.111 – GENERAL PHYSICS LABORATORY I Accelerometers 1L EARNING OBJECTIVES At the conclusion of this activity you should be able to: • Use your smartphone to collect acceleration data. • Use measured acceleration to estimate the distance of a free fall • Use measured acceleration to estimate kinematic quantities that describe an elevator ride. 2B ACKGROUND 2.1A CCELERATION,VELOCITY, AND POSITION We know from Classical Mechanics that we can move between position, velocity, and acceleration by repeatedly taking time derivatives of the position of an object. Similarly, starting from acceleration, we can take subsequent integrals with respect to time to obtain velocity and position respectively. Description Differential Form Integral Form Z Position ~x ~x ~vdt Æ d~x Z Velocity ~v ~v ~adt Æ dt Æ d 2~x d~v Acceleration ~a ~a Æ dt 2 Æ dt 2.2C OLLECTING DATA WITH A SMARTPHONE Most modern smart phones come packed with sensors that make them ideal to use as physics instru- ments. Many cell phones come packaged with an air pressure sensor, light meter, 3-axis accelerometers, 3-axis magnetometer, gyroscope, and of course a microphone. Many great physics measurements can be made using your smart phone. Several apps exist for collecting data from these packaged sensors. For this lab activity, we will use the PhyPhox app. You may download the app to your phone here: https://phyphox.org/ Revised: Wednesday 10th March, 2021 16:32 ©2014 J. Reid Mumford PhyPhox is also available in both the Google Play and Apple app stores. 2.3A CCELEROMETERS Your smartphone is packaged with a small integrated circuit package called a Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS). -

Development of MEMS Capacitive Sensor Using a MOSFET Structure

Extended Summary 本文は pp.102-107 Development of MEMS Capacitive Sensor Using a MOSFET Structure Hayato Izumi Non-member (Kansai University, [email protected]) Yohei Matsumoto Non-member (Kansai University, [email protected] u.ac.jp) Seiji Aoyagi Member (Kansai University, [email protected] u.ac.jp) Yusaku Harada Non-member (Kansai University, [email protected] u.ac.jp) Shoso Shingubara Non-member (Kansai University, [email protected]) Minoru Sasaki Member (Toyota Technological Institute, [email protected]) Kazuhiro Hane Member (Tohoku University, [email protected]) Hiroshi Tokunaga Non-member (M. T. C. Corp., [email protected]) Keywords : MOSFET, capacitive sensor, accelerometer, circuit for temperature compensation The concept of a capacitive MOSFET sensor for detecting voltage change, is proposed (Fig. 4). This circuitry is effective for vertical force applied to its floating gate was already reported by compensating ambient temperature, since two MOSFETs are the authors (Fig. 1). This sensor detects the displacement of the simultaneously suffer almost the same temperature change. The movable gate electrode from changes in drain current, and this performance of this circuitry is confirmed by SPICE simulation. current can be amplified electrically by adding voltage to the gate, The operating point, i.e., the output voltage, is stable irrespective i.e., the MOSFET itself serves as a mechanical sensor structure. of the ambient temperature change (Fig. 5(a)). The output voltage Following this, in the present paper, a practical test device is has comparatively good linearity to the gap length, which would fabricated.