Louise Bennett and the Mento Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

Secondary Level Music Teacher Training Institutions in Jamaica: a Historical Study

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Secondary Level Music Teacher Training Institutions in Jamaica: A Historical Study Garnet Christopher Lloyd Mowatt University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Mowatt, Garnet Christopher Lloyd, "Secondary Level Music Teacher Training Institutions in Jamaica: A Historical Study" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 705. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/705 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECONDARY LEVEL MUSIC TEACHER TRAINING INSTITUTIONS IN JAMAICA: A HISTORICAL STUDY A Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi By GARNET C.L. MOWATT July 2013 Copyright Garnet C.L. Mowatt 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Jamaica, one of the many countries of the Commonwealth Caribbean, is known for its rich musical heritage that has made its impact on the international scene. The worldwide recognition of Jamaica’s music reflects the creative power of the country’s artists and affects many sectors of the island’s economy. This has lead to examination and documentation of the musical culture of Jamaica by a number of folklorists and other researchers. Though some research has focused on various aspects of music education in the country, very little research has focused on the secondary level music teacher education programs in Jamaica. -

Reviewarticles How Readable Is the Caribbean Soundscape?

New West Indian Guide 89 (2015) 61–68 nwig brill.com/nwig Review Articles ∵ How Readable is the Caribbean Soundscape? New Contributions to Music Bibliography Kenneth Bilby Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington dc 20013, u.s.a. [email protected] From Vodou to Zouk: A Bibliographic Guide to Music of the French-Speaking Caribbean and its Diaspora. John Gray. Nyack ny: African Diaspora Press, 2010. xxxiv + 201 pp. (Cloth us$79.95) Jamaican Popular Music, from Mento to Dancehall Reggae: A Bibliographic Guide. John Gray. Nyack ny: African Diaspora Press, 2011. xvii + 435 pp. (Cloth us$99.95) Afro-Cuban Music: A Bibliographic Guide. John Gray. Nyack ny: African Dias- pora Press, 2012. xiv + 614 pp. (Cloth us$124.95) Baila! A Bibliographic Guide to Afro-Latin Dance Musics from Mambo to Salsa. John Gray. Nyack ny: African Diaspora Press, 2013. xv + 661 pp. (Cloth us$124.95) Times have certainly changed for the study of Caribbean music. Not so long ago, one might have realistically hoped to fit a comprehensive bibliography of the music of the entire region between the covers of a single volume. Such was John Gray’s ambition some two decades ago when he systematically began to assemble the materials that ended up distributed across these four vol- umes. (At one point, the plan was actually to combine Latin America and the © kenneth bilby, 2015 | doi: 10.1163/22134360-08901001 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (cc-by-nc 3.0) License. -

Vallenato En Colombia. Estoy Aquí Pero Mi Alma Está Allá. Vallenato En Colombia

Vallenato en Colombia. Estoy aquí pero mi alma está allá. Vallenato en Colombia. Estoy aquí pero mi alma está allá, 2019 © Julio Cesar Galeano González Impresión: mayo de 2019. Ilustraciones Diego Reyes Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida, almacenada o trasmitida por ningún medio sin previo aviso del autor. A mi mamá. Es más bonito cuando lo escuchamos juntos. Índice El corazón confía a tus paisajes volver agún día-----------------------------11 "Ay, hombe", canta un madrileño-----------------------------------------------21 Cuando la guacharaca es más grande que la guacharaquera----------------29 La caja está en buenas manos---------------------------------------------------37 El cirujano alemán---------------------------------------------------------------43 Vallenato en Bogotá, aquí estoy pero mi alma está allá----------------------53 El corazón confía a tus paisajes volver algún día Un parrandero que nació lejos de la parranda, consciente de que la fe mueve montañas, pero no acordeones llegó al epicentro de amores bonitos, placeres y desengaños en época de Festival. Aquí los versos sutiles se vuelven tsunamis que como el Guatapurí arrasan con todo a su paso excepto con ese sentimiento vallenato, que no sale de Valledupar sino del alma. Dicen que cuando el niño está A mí me intentaron poner música todavía en la barriga de su mamá clásica cuando estaba en la panza o está recién nacido se le debe de mi mamá, pero di la pelea y las poner música clásica, para que patadas, señal de mi inconformismo, sea más inteligente y más sensi- ganaron la batalla. Por supuesto no ble. Estoy seguro de que ni Rafael quería causarle ningún malestar y Escalona ni Leandro Díaz escucharon lo único que pedía era un poquitico a Beethoven o a Mozart cuando eran más de sabor, entonces ella compla- bebés y entre los dos crearon más de ciente como siempre sacó los case- 300 canciones vallenatas que son tes de estos dos poetas y fueron sus prueba de esa inteligencia y sensibi- letras las que nos acompañaron a lidad con la que nacen los artistas. -

Bambuco, Tango and Bolero: Music, Identity, and Class Struggles in Medell´In, Colombia, 1930–1953

BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 by Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado B.S. in Music (harpsichord), Ponti¯cia Universidad Javeriana, 1997 M.A. in Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Music in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2006 BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation explores the articulation of music, identity, and class struggles in the pro- duction, reception, and consumption of sound recordings of popular music in Colombia, 1930- 1953. I analyze practices of cultural consumption involving records in Medell¶³n,Colombia's second largest city and most important industrial center at the time. The study sheds light on some of the complex connections between two simultaneous historical processes during the mid-twentieth century, mass consumption and socio-political strife. Between 1930 and 1953, Colombian society experienced the rise of mass media and mass consumption as well as the outbreak of La Violencia, a turbulent period of social and political strife. Through an analysis of written material, especially the popular press, this work illustrates the use of aesthetic judgments to establish social di®erences in terms of ethnicity, social class, and gender. Another important aspect of the dissertation focuses on the adoption of music gen- res by di®erent groups, not only to demarcate di®erences at the local level, but as a means to inscribe these groups within larger imagined communities. -

Issue 195.Pmd

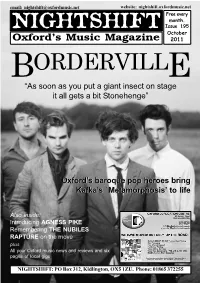

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 195 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 BORDERVILLE “As soon as you put a giant insect on stage it all gets a bit Stonehenge” Oxford’sOxford’s baroquebaroque poppop heroesheroes bringbring Kafka’sKafka’s `Metamorphosis’`Metamorphosis’ toto lifelife Also inside: Introducing AGNESS PIKE Remembering THE NUBILES RAPTURE on the move plus All your Oxford music news and reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Truck Store is set to bow out with a weekend of live music on the 1st and 2nd October. Check with the shop for details. THE SUMMER FAYRE FREE FESTIVAL due to be held in South Park at the beginning of September was cancelled two days beforehand TRUCK STORE on Cowley Road after the organisers were faced with is set to close this month and will a severe weather warning for the be relocating to Gloucester Green weekend. Although the bad weather as a Rapture store. The shop, didn’t materialise, Gecko Events, which opened back in February as based in Milton Keynes, took the a partnership between Rapture in decision to cancel the festival rather Witney and the Truck organisation, than face potentially crippling will open in the corner unit at losses. With the festival a free Gloucester Green previously event the promoters were relying on bar and food revenue to cover occupied by Massive Records and KARMA TO BURN will headline this year’s Audioscope mini-festival. -

SOUNDS of VACATION

Jocelyne Guilbault and Timothy Rommen, editors SOUNDS of VACATION Political Economies of Caribbean Tourism SOUNDS of VACATION SOUNDS Jocelyne Guilbault and of VACATION timothy Rommen, editoRs Political Economies of Caribbean Tourism Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker and typeset in Whitman and Avenir by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Guilbault, Jocelyne, editor. | Rommen, Timothy, editor. Title: Sounds of vacation : political economies of Caribbean tourism / Jocelyne Guilbault and Timothy Rommen, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018055385 (print) | lccn 2019014499 (ebook) isbn 9781478005315 (ebook) isbn 9781478004288 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478004882 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Music and tourism—Caribbean Area. | Music— Social aspects—Caribbean Area. | Music—Economic aspects— Caribbean Area. | Tourism—Political aspects—Caribbean Area. Classification: lcc ml3917.c38 (ebook) | lcc ml3917.c38 s68 2019 (print) | ddc 306.4/842409729—dc23 lc record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2018055385 coveR aRt: Courtesy LiuNian/E+/Getty Images. Contents Acknowledgments · vii Prologue · 1 STEVEN FELD intRoduction · The Political Economy of Music and Sound Case Studies in the Caribbean Tourism Industry · 9 JOCELYNE GUILBAULT -

The Swell and Crash of Ska's First Wave : a Historical Analysis of Reggae's Predecessors in the Evolution of Jamaican Music

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2014 The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Lobo-Gilbert, Erik R., "The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music" (2014). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 366. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/366 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert CSU Monterey Bay MPA Recording Technology Spring 2014 THE SWELL AND CRASH OF SKA’S FIRST WAVE: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF REGGAE'S PREDECESSORS IN THE EVOLUTION OF JAMAICAN MUSIC INTRODUCTION Ska music has always been a truly extraordinary genre. With a unique musical construct, the genre carries with it a deeply cultural, sociological, and historical livelihood which, unlike any other style, has adapted and changed through three clearly-defined regional and stylistic reigns of prominence. The music its self may have changed throughout the three “waves,” but its meaning, its message, and its themes have transcended its creation and two revivals with an unmatched adaptiveness to thrive in wildly varying regional and sociocultural climates. -

Salvati Dal Rock and Roll

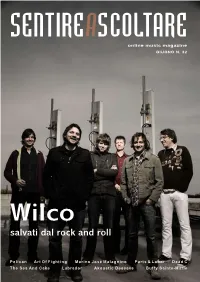

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GIUGNO N. 32 Wilco salvati dal rock and roll Hans Appelqvist King Kong Laura Veirs Valet Keren Ann Feist Low PelicanStars Of The Art Lid Of Fighting Smog I Nipoti Marino del CapitanoJosé Malagnino Cristina Zavalloni Parts & Labor Billy Nicholls Dead C The Sea And Cake Labrador Akoustic Desease Buffys eSainte-Marie n t i r e a s c o l t a r e WWW.AUDIOGLOBE.IT VENDITA PER CORRISPONDENZA TEL. 055-3280121, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] DISTRIBUZIONE DISCOGRAFICA TEL. 055-328011, FAX 055 3280122, [email protected] MATTHEW DEAR JENNIFER GENTLE STATELESS “Asa Breed” “The Midnight Room” “Stateless” CD Ghostly Intl CD Sub Pop CD !K7 Nuovo lavoro per A 2 anni di distan- Matthew Dear, uno za dal successo di degli artisti/produt- critica di “Valende”, È pronto l’omonimo tori fra i più stimati la creatura Jennifer debutto degli Sta- del giro elettronico Gentle, ormai nelle teless, formazione minimale e spe- sole mani di Mar- proveniente da Lee- rimentale. Con il co Fasolo, arriva al ds. Guidata dalla nuovo lavoro, “Asa Breed”, l’uomo di Detroit, si nuovo “The Midnight Room”, sempre su Sub voce del cantante Chris James, voluto anche rivela più accessibile che mai. Sì certo, rima- Pop. Registrato presso una vecchia e sperduta da DJ Shadow affinché partecipasse alle regi- ne il tocco à la Matthew Dear, ma l’astrattismo casa del Polesine ed ispirato forse da questa strazioni del suo disco, la formazione inglese usuale delle sue produzioni pare abbia lasciato sinistra collocazione, il nuovo album si districa mette insieme guitar sound ed elettronica, ri- uno spiraglio a parti più concrete e groovy.