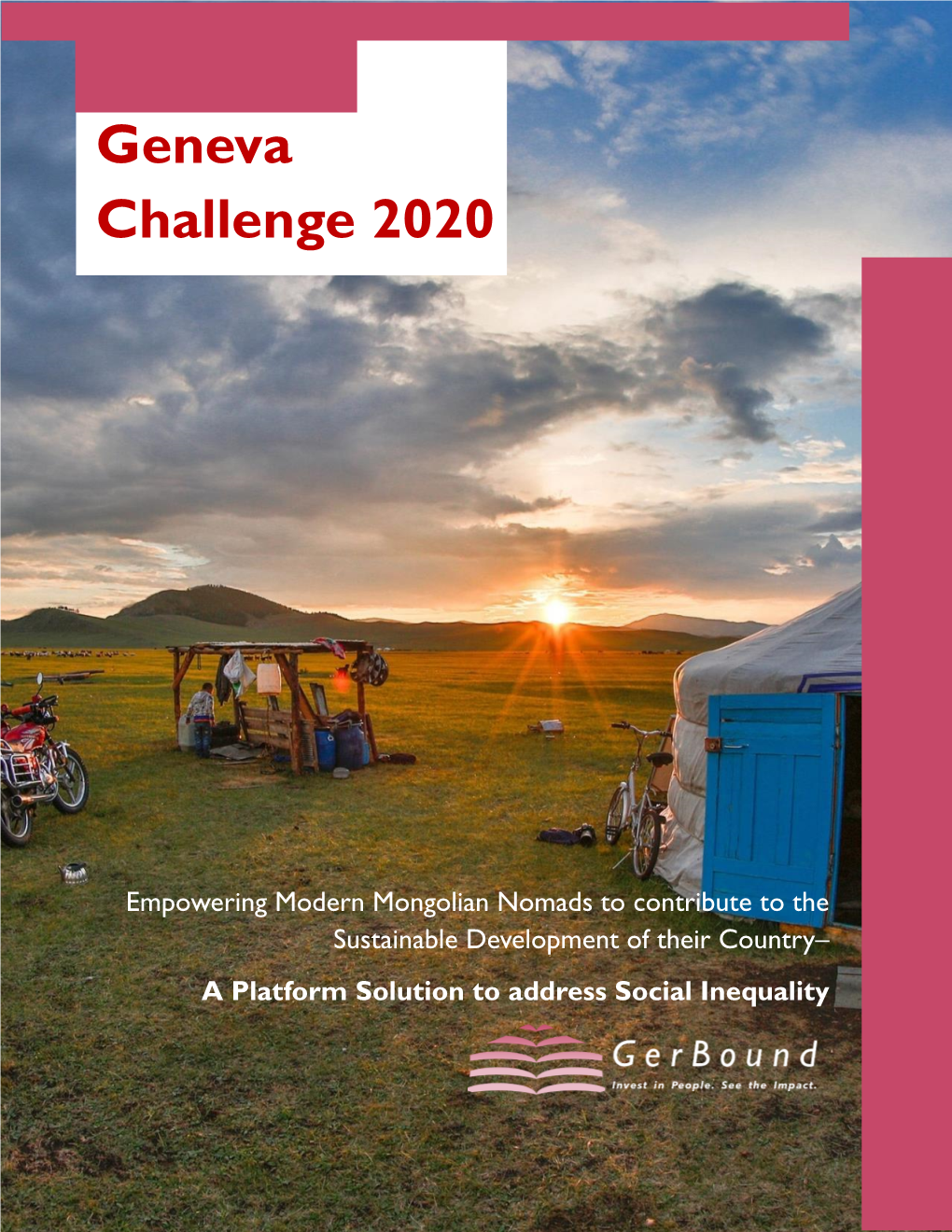

Geneva Challenge 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sixtieth Report 1968

P.A.C. NO. 216 (FOURTH LOK SABHA) SIXTIETH REPORT AppROpRS 41 'ON ACCOUNTS *AILWAYS), AND AUDIT REPORT (RA:LWAYS) 1968 LOX SABXSA SECRETARIAT N Ern .DELfiI. LIST OF AUTHORISED AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF LOK SABRA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS S1. Nunc:of A@nt Nnme'of A&cnt No. %? Et. No. - . I ANDHRA' PRADESH xn. Ch~rlca~Lem~& Com- 30 pany, ror, Mahatma I. ;~ndhri ~nivcrshy Geneivl 8 Gandhi Road, Opposite r Coopcratlve Stora Ltd., Clock Tom, Fort, W.ttoir(vi~ptnam). Bombay. 3. G.R.Lnkshmipathy 'Cherty The Current Book House, 60 and Sons, Gend My- Mwti Lane, Raghunath chants md News Agents, DPdaji Sttett, Bombay-:. Newpet, Qmndragiri, Chinoor District. Deem Book Stall, FCE 65 won Coliego Road, P00nr-4. 3. Wutgn Bod; .Depot, PM Mls. Ushr Book Depot. S Bpypy, Gauhau. 8jlA Chim Razar,l(knn KouS c. Girgnurn Road, Bombay-z BR. Mla. Peoples Book House, 16 Opp. Jaganmohan Palace, Mysoex. 5, Vijrg Stores, Station Road, AnmJ, 17. Information Ccnrre, 6. New Ordq Boot 63 Govemmcnf of hbsthm, Canpmy, EUtr BoJge, Tripolia, Jaipur City. Ahmedsbd-6. at. Nm& C~~WY 44 d.,3, Old fhtrt kbuse 21 ' htr~~t.G~N- 26 . % rj. Wr. MadBooL HOW 1 BB, W Lwr, (5) (f) lt~ignalin,:u It signallingtt . I3 "appointment " "apportionment" 26 compliedlr 6 "a h4adI1 "ma terali seit "ou tlayln;It tldirnentionsfl l1 speciafi cally" Commi s sionI1 "utili sation" llhoulagefl 'teirernessu 5 .t Feletn "all 2 "bogiet'" 27 It drown" 28 surplul" UsurplusN 1 (Thixi Lok Sabha,"I1Third Lok " % jabha) ;lt 3 Six" I* 2 11 1969" " 1959" sub para 2 3.31 7 I% 1,04 lakhsU I% 1.04 lakhsVt 3.53 35 19 at." tlastl ' ' "regradedu 4.3 2 !!regradingn 4.8 16 ''regrading" 4.8 lest "Appendix I 1. -

Sustainable Housing Scoping Study

Funded by the European Union SUSTAINABLE HOUSING ADDRESSING SCP IN THE HOUSING SECTOR SCOPING STUDY SUSTAINABLE HOUSING ADDRESSING SCP IN THE HOUSING SECTOR SCOPING STUDY © 2019 EU Acknowledgement This study was prepared on behalf of the EU SWITCH- Asia Sustainable Consumption and Production Facility (SCPF) by Madeline Schneider, Carolina Borges, Jessica Weir, Anton Barckhausen, Jonas Restle, Mikael P. Henzler from adelphi consult GmbH and Apurva Singh, Isha Sen, Rashi, Suhani Gupta, Shruti Isaar, Gitika Goswami, Zeenat Niazi from Development Alternatives. It was supervised by Puja Sawhney and Arab Hoballah. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. SCP SCOPING STUDY • SUSTAINABLE HOUSING Table of contents 1 Context ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objective of the study ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Definition of sustainable housing ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Relevance of sustainable housing ....................................................................................... 4 1.3.1 Sustainable housing in the context of the global agenda setting processes .......................... 4 1.3.2 Potential of the housing sector to achieve greenhouse gas (GHG) and energy savings ......... 5 1.3.3 Sustainable housing -

Investment in Mongolia

Investment in Mongolia KPMG in Mongolia 2016 Edition CONTENTS 1 COUNTRY OUTLINE 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Geography and climate 6 1.3 History 6 1.4 Political system 7 1.5 Population, language and religion 7 1.6 Currency 8 1.7 Public holidays 8 2 BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT 10 2.1 Mongolian economy overview 10 2.2 Economic trading partners 11 Exports 11 Imports 11 2.3 Business culture 11 2.4 Free trade zones 12 2.5 Foreign exchange controls 12 3 INVESTMENT CLIMATE FOR FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT 14 3.1 Foreign investment opportunities 14 3.2 Foreign investment legislation 14 3.3 Commencing business in Mongolia 15 Practical considerations 15 Registration 15 Mergers, acquisitions and restructurings 16 Exit strategy 16 3.4 Financing 17 3.5 Intellectual property 17 Copyright 17 Trademarks and trade names 17 Patents 18 4 REPORTING, AUDITING AND THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT 20 4.1 Financial reporting 20 4.2 Auditing 21 4.3 Regulatory environment 21 Competition law 21 © 2016 KPMG Audit LLC, the Mongolian member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. 2 / Investment in Mongolia Corporate governance 22 Land ownership and use 22 Anti-corruption law 23 Arbitration 23 5 TAXATION 25 5.1 General tax law 25 Overview 25 Rights and duties – taxpayers and tax authorities 26 Tax reporting and payments 26 Tax audits 26 Debt collection 27 5.2 Corporate tax 27 Overview of the corporate tax system 27 Taxable income 28 Losses 28 5.3 Transfer pricing 29 5.4 Double tax agreements -

MONGOLIA CONSTRAINTS ANALYSIS a Diagnostic Study of the Most Binding Constraints to Economic Growth in Mongolia

The production of this constraints analysis was led by the partner governments, and was used in the development of a Millennium Challenge Compact or threshold program. Although the preparation of the constraints analysis is a collaborative process, posting of the constraints analysis on this website does not constitute an endorsement by MCC of the content presented therein. 2014-001-1569-02 MONGOLIA CONSTRAINTS ANALYSIS A diagnostic study of the most binding constraints to economic growth in Mongolia August 18, 2016 Produced by National Secretariat for the Second Compact Agreement between the Government of Mongolia and the Millennium Challenge Corporation of the USA With technical assistance from the Millennium Challenge Corporation i Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ vi Glossary of Terms .......................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. -

Public to Have Say on BC Parking Woes Wakefield Court, Which Parallels by JOSEPH A

APR 12 2000 Coach Neff leaves b1g shoes 0 see page 14 --------------~ ~----------~ 'no spring in his step Public to have say on BC parking woes Wakefield Court, which parallels By JOSEPH A. PHILLIPS Longmeadow, seeking additional A public hearing on proposed new postings - and other residents parking restrictions in a neighborhood suggesting restrictions throughout the near Bethlehem Central High School entire neighborhood. tops the agenda at tonight's Bethlehem "But in order to do anything, I have to town board meeting. hold a public hearing," she said. "And, in The proposed law would restrict order to hold a public hearing, I need to parking along know where I'm both sides of headed with all Grantwood Aven of this. I can't ue, in the Brook I can't just announce at just announce at field development Wednesday across Delaware Wednesday night's meeting night's meeting Avenue from the that I'm banning parking that I'm banning school, to a single parking on all hour between 7:30 on all these streets. these streets." a.m. and 2:30 p.m. Sheila Fuller She will seek on school days - the board's guid- preventing all-day ance, she said, parking by student drivers unable to park on whether to hold additional public in the school's limited lots. hearings aimed at expanding the parking The latest in a series of postings restrictions in Brookfield. approved by the town board since 1996 But, she maintained that restricting for various streets in Brookfield, the parking in the neighborhood would not Grantwood signs were requested by solve the problem of an increasing residents concerned about safety, traffic number of students driving to the high movement and property damage school rather than taking school buses. -

Mongolian European Chamber Of

MONGOL Since 1991 the MESSENGER 500 ¥ No. 07-08 (1076-1077) MONGOLIA’S FIRST ENGLISH WEEKLY PUBLISHED BY MONTSAME NEWS AGENCY Friday, February 17, 2012 Mongolia Economic Happy Tsagaan Sar! Forum planned for early March The Mongolian Economic Forum 2012 will run on March 5-6. At a February 10 press conference, organizers of the forum reported about the preparations and measures for the forum. As of information given by MP S. Oyun; Deputy Finance Minister Ch.Gankhuyag; Ch.Khashchuluun, head of the National Development and Innovation Committee; and P.Tsagaan, senior advisor to the President, the forum that is to be organized for the third time, will run this year under the motto ‘Together for Development’. The forum will have sub-meetings under themes on economic development, social policy and competitiveness, and bring together over 1000 foreign and domestic participants. During the forum, it is planned to publicly introduce Mongolia’s development forum until 2021 issued by Open Society. MP S. Oyun said, “In reality, why isn’t poverty decreasing while the economy has grown over the past five or six years. We believe that issues on how to decrease poverty and what should be done for the fruits of economic growth to improve livelihoods will develop into hot discussions during the forum. For instance, the statistical figures on poverty percentages are very confusing. The National Statistical Committee evaluates the poverty rate at 39 percent while the World Bank says it is lower using a different methodology to evaluate poverty. Therefore, -

Request for Project/Programme Funding from the Adaptation Fund

REQUEST FOR PROJECT/PROGRAMME FUNDING FROM THE ADAPTATION FUND The annexed form should be completed and transmitted to the Adaptation Fund Board Sec- retariat by email or fax. Please type in the responses using the template provided. The instructions attached to the form provide guidance to filling out the template. Please note that a project/programme must be fully prepared (i.e., fully appraised for feasi- bility) when the request is submitted. The final project/programme document resulting from the appraisal process should be attached to this request for funding. Complete documentation should be sent to: The Adaptation Fund Board Secretariat 1818 H Street NW MSN P4-400 Washington, D.C., 20433 U.S.A Fax: +1 (202) 522-3240/5 Email: [email protected] 1 PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL TO THE ADAPTATION FUND PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Project/Programme Category: Regular Country/Cities: Mongolia/ Ulaanbaatar Title of Project/Programme: Flood Resilience in Ulaanbaatar Ger Ar- eas - Climate Change Adaptation through community-driven small-scale protective and basic-services interventions Type of Implementing Entity: Multilateral Implementing Entity Implementing Entity: UN-Habitat Executing Entity/ies: Programme Execution Unit (PEU) UNOPS, with the Municipality of Ulaanbaatar (MUB) and the Governor’s Office, District Gover- nors and Ger-Communities within Songino- khairkhan, Bayanzurkh and Sukhbaatar Dis- tricts; INGOs and LNGOs; Ministry of Envi- ronment and Tourism (MoET). Amount of Financing Requested: US$ 4.5 million 1. Project Background and Context Mongolia is a landlocked country located in North- east Asia between Russia and China with a total land area of 1,564,116 square kilometres. -

Access to Finance: Developing the Microinsurance Market in Mongolia

Access to Finance Developing the Microinsurance Market in Mongolia Mongolia experienced a challenging transition from socialist economy to market economy from 1990 onwards. Its commercial insurance market is still at its infancy, with gross written premiums in 2013 amounting to only 0.54% of gross domestic production. ADB undertook this technical assistance study to support microinsurance development in Mongolia. The study provides an overview of the development of Mongolia’s insurance market in ACCESS TO FINANCE general and the microinsurance segment in particular, then identifies gaps in the insurance regulatory framework that need to be bridged to expand microinsurance coverage to more households. DEVELOPING THE MICROINSURANCE MARKET IN MONGOLIA About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. ISBN Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines ACCESS TO FINANCE DEVELOPING THE MICROINSURANCE MARKET IN MONGOLIA Access to Insurance Initiative Kelly Rendek and Martina Wiedmaier-Pfister © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

U.S.$5,000,000,000 GLOBAL MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAM the GOVERNMENT of MONGOLIA Bofa Merrill Lynch Deutsche Bank HSBC J.P. Morgan

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM U.S.$5,000,000,000 GLOBAL MEDIUM TERM NOTE PROGRAM THE GOVERNMENT OF MONGOLIA Under this U.S.$5,000,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Program (the “Program”), the Government of Mongolia (the “Issuer”) may from time to time issue notes (the “Notes”) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined in “Subscription and Sale”). Notes may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively, “Bearer Notes” and “Registered Notes”). The aggregate nominal amount of all Notes to be issued under the Program will not exceed U.S.$5,000,000,000 or its equivalent in other currencies at the time of agreement to issue. The Notes and any relative Receipts and Coupons (as defined herein), will constitute direct, unconditional, unsubordinated and (subject to the Terms and Conditions of the Notes (the “Conditions”)) unsecured obligations of the Issuer and rank pari passu without any preference among themselves and (save for certain obligations required to be preferred by law) equally with all other unsecured and unsubordinated debt obligations of the Issuer. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers. References in this Information Memorandum to the relevant Dealer shall, in the case of an issue of Notes being (or intended to be) subscribed for by more than one Dealer, be to all Dealers agreeing to subscribe for such Notes. Approval in-principle has been granted for the listing and quotation of Notes that may be issued pursuant to the Program and which are agreed at or prior to the time of issue thereof to be so listed and quoted on the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (the “SGX-ST”). -

From the Editor in This Issue

Volume 2 Number 1 June 2004 “The Bridge between Eastern and Western cultures” From the Editor In This Issue • Bronze Age Steppe Archaeology When did the “Silk Road” begin? To silk made its way to the Medi- a considerable degree, the answer terranean world by Han and Roman • The Antiquity of the Yurt depends on how we interpret the times were hardly unique. In short, archaeological evidence about Inner what we see here is a conscious • The Burial Rite in Sogdiana Asian nomads and their relations effort to argue for “globalization” with sedentary peoples. Long- before the advent of the modern • The Caravan City of Palmyra accepted views about the Silk Road global economy. • The Tea and Horse Road in China situate its origins in the interaction between the Han and the Xiongnu Michael Frachetti’s contribution to • Klavdiia Antipina, Ethnographer beginning in the second century BCE, this issue suggests that in learning of the Kyrgyz as related in the first instance in the about the world of nomads, we might Han histories. As the stimulating best start by thinking about local • Mongolia Today recent book by Nicola Di Cosmo networks, not migrations over long reminds us though, if we are to gain distances. Of particular interest here • The Khotan Symposium in London an Inner Asian perspective on the is the possibility that patterns of development of nomadic power we short-distance migration from need to distinguish carefully lowland winter settlements to pastures in the mountains can be Next Issue between the picture drawn from those written sources and what the documented from the archaeological 1 record for earlier millennia. -

Authenticity and Adaptation : the Mongol Ger As a Contemporary Heritage Paradox

This is a repository copy of Authenticity and Adaptation : The Mongol Ger as a Contemporary Heritage Paradox. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/110122/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Schofield, Arthur John orcid.org/0000-0001-6903-7395 and Paddock, Charlotte (2017) Authenticity and Adaptation : The Mongol Ger as a Contemporary Heritage Paradox. International Journal of Heritage Studies. pp. 347-361. ISSN 1352-7258 https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1277775 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Authenticity and Adaptation: The Mongol Ger as a Contemporary Heritage Paradox Charlotte Paddock and John Schofield Department of Archaeology, University of York, UK YO17EP Abstract The Mongol Ger is a transportable felt tent deriving from an ancient nomadic civilization. The structure encapsulates a specific Mongolian nomadic cultural identity by encompassing a way of life based upon pastoral migration, complex familial relationships and hierarchies, and spiritual beliefs. -

BDSEC JSC Weekly Market Update Mongolia’S Largest Broker December 7, 2020

BDSEC JSC Weekly Market Update Mongolia’s Largest Broker December 7, 2020 MSE Market Commentary MSE Top Movers • MSE Top-20 Index was up 0.42%, MSE A Index ended higher 0.18%, When will MSE delist some companies? (marketinfo.mn) and MSE B Index decreased 0.01% Market capitalization amounted to • Mongolian Stock Exchange was established 30 years ago, and 2,606.3 billion and average volume of 134,654 shares were traded at an currently 194 companies listed on MSE. Of which businesses of many Indexes Points % Change aggregate average value of MNT 20.4 million. companies have already been halted, some companies have not held MSE Top-20 Index 17.658.44 +0.42% • APU (APU) was the most actively traded stock with an aggregate value shareholders meeting and violated interest of their shareholders, of MNT 19.8 million. Following was Erdene Resource Dev. (ERDN) with and stocks of some companies have not been traded in the market. MSE A Index 8,117.58 +0.18% its total value of MNT 11.3 million. However, Mongolian Stock Exchange has not taken arrangement on MSE B Index 7,326.15 -0.01% • Tier 1 top gainers of the week were Mongolian Mortgage Corp. (MIK), the matter till now. LendMN (LEND), and Bayangol Hotel (BNG) on the other hand BDSec • Looking at the statistics of stock trading, stocks of 58% out of all Market Summary Value (USD) (BDS) lost as much as 8.07% of its value and closed at MNT 791.5. companies listed on MSE have not been traded on the market for last Market capitalization 914,491,673 Mongolia Headlines one year.