Atlanta Housing Authority's Fiscal Year 2006 Implementationn Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary ................................................................5 Summary of Resources ...........................................................6 Regionally Important Resources Map ................................12 Introduction ...........................................................................13 Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value .................21 Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ..................................48 Areas of Scenic and Agricultural Value ..............................79 Appendix Cover Photo: Sope Creek Ruins - Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area/ Credit: ARC Tables Table 1: Regionally Important Resources Value Matrix ..19 Table 2: Regionally Important Resources Vulnerability Matrix ......................................................................................20 Table 3: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ...........46 Table 4: General Policies and Protection Measures for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ................47 Table 5: National Register of Historic Places Districts Listed by County ....................................................................54 Table 6: National Register of Historic Places Individually Listed by County ....................................................................57 Table 7: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ............................77 Table 8: General Policies -

The Politics of Atlanta's Public Housing

THE POLITICS OF ATLANTA’S PUBLIC HOUSING: RACE, PLANNING, AND INCLUSION, 1936-1975 By AKIRA DRAKE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Planning and Public Policy Written under the direction of James DeFilippis And approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey MAY, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Politics of Atlanta’s Public Housing: Race, Planning, and Inclusion, 1936-1975 By AKIRA DRAKE Dissertation Director: James DeFilippis The purpose of this research is threefold: to theorize the political viability of the public housing development as a political opportunity structure; to understand the creation, marginalization, and demolition of this political opportunity structure in Atlanta; and to explicate the movements from within the public housing development that translated to a more empowered residential base, and more livable communities in Atlanta, GA between the 1936 and 1975. The literature on the positive productive functions of public housing is interspersed within the literature on the politics of public housing policies (at the national level), the politics of public housing developments (at the local level), the production of a racial geography in the City of Atlanta, and the productive functions of welfare institutions (including, but not limited to, public housing developments). Further, this project attempts to understand empirical benefits of political opportunity structures, particularly as it relates to low-income and minority housing movements in the city of Atlanta. Theoretically, political opportunity structures provide a neutral platform for low-income city dwellers that have historically been denied the legal means to challenge neighborhood change, and participate in formal urban political processes ii and institutions. -

TRANSFORMATION PLAN UNIVERSITY AREA U.S.Department of Housing and Urban Development ATLANTA HOUSING AUTHORITY

Choice Neighborhoods Initiative TRANSFORMATION PLAN UNIVERSITY AREA U.S.Department of Housing and Urban Development ATLANTA HOUSING AUTHORITY ATLANTA, GEORGIA 09.29.13 Letter from the Interim President and Chief Executive Officer Acknowledgements Atlanta Housing Authority Board of Commissioners Atlanta University Center Consortium Schools Daniel Halpern, Chair Clark Atlanta University Justine Boyd, Vice-Chair Dr. Carlton E. Brown, President Cecil Phillips Margaret Paulyne Morgan White Morehouse College James Allen, Jr. Dr. John S. Wilson, Jr., President Loretta Young Walker Morehouse School of Medicine Dr. John E. Maupin, Jr., President Atlanta Housing Authority Choice Neighborhoods Team Spelman College Joy W. Fitzgerald, Interim President & Chief Executive Dr. Beverly Tatum, President Officer Trish O’Connell, Vice President – Real Estate Development Atlanta University Center Consortium, Inc. Mike Wilson, Interim Vice President – Real Estate Dr. Sherry Turner, Executive Director & Chief Executive Investments Officer Shean L. Atkins, Vice President – Community Relations Ronald M. Natson, Financial Analysis Director, City of Atlanta Kathleen Miller, Executive Assistant The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Melinda Eubank, Sr. Administrative Assistant Duriya Farooqui, Chief Operating Officer Raquel Davis, Administrative Assistant Charles Forde, Financial Analyst Atlanta City Council Adrienne Walker, Grant Writer Councilmember Ivory Lee Young, Jr., Council District 3 Debra Stephens, Sr. Project Manager Councilmember Cleta Winslow, Council District -

Atlanta Office of Public Housing Commemorates the 75Th Anniversary of the US Housing Act 1937-2012 October 2012

Special thanks to: Sherrill C. Dunbar, Program Analyst Deidre Reeves, Public Housing Revitalization Specialist Cover photo: Olmsted Homes, the first public housing project built in Georgia after passage of the U.S. Housing Act of 1937. Atlanta Office of Public Housing Commemorates the 75th Anniversary of the U.S. Housing Act 1937-2012 October 2012 U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Region IV Five Points Plaza 40 Marietta Street Atlanta, Georgia 30303-2806 Greetings All: On behalf of the staff at the Atlanta Office of Public Housing, it is my pleasure to present our commemorative booklet marking the 75th anniversary of the 1937 U. S. Housing Act. The commemoration of the 1937 U. S. Housing Act has special meaning in the state of Georgia, as it was in Georgia that the first public housing development in the United States, Techwood Homes in Atlanta, was constructed. The evolution of Techwood homes into today’s Centennial Place, a mixed-income community, is a testament of just how far public housing has come since 1937. However, there are many more shining examples throughout Georgia, as you will see in the 25 public housing agencies profiled in this publication. Today, 75 years after the passage of the 1937 Housing Act, there are more than 3300 housing authorities nationwide, and 185 in the state of Georgia alone. Housing authorities are still charged with providing decent, safe and affordable housing to low-income citizens, as evidenced by the more than 200,000 Georgia residents that participate in HUD’s Public Housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs. -

Community Assessment

CCommunityommunity AAssessmentssessment - 44.1..1. NNaturalatural RResourcesesources 4.1 NATURAL RESOURCES Environmental Planning Criteria Environmental condi ons place certain opportuni es and constraints on the way that land is u lized. Many areas and resources that are vulnerable to the impacts of development require protec on by government regula on and by other measures. Soil characteris cs, topography, and the frequency of ood- ing are just a few of the factors that a ect where development can safely and feasibly be accommodated. Other areas such as wetlands, forest areas, and sensi ve plant and animal habitats are also vulnerable to the impacts of development. As the City of Atlanta and the surrounding areas con nue to grow, the conser- va on of exis ng and nding opportuni es for the protec on of environmen- tally-sensi ve and ecologically-signi cant resources is becoming increasingly Cha ahoochee River is the City and the important. The City of Atlanta’s vision is to balance growth and economic de- Region’s main water resource. velopment with protec on of the natural environment. This is to be done in conjunc on with the statewide goal for natural resources, which is to con- serve and protect the environmental and natural resources of Georgia’s com- muni es, regions, and the State. The City of Atlanta takes pride in the diversity of natural resources that lie within its city limits. Whether enjoying the vista that the Cha ahoochee River o ers or making use of the many parks and trails that traverse the city, or the urban forest, the City of Atlanta has an abundance of natural resources which need protec on and management. -

TECHWOOD HOMES, BUILDING 16 HABS No. GA-2257-S TECHWOOD/CLARK HOWELL HOMES REDEVELOPMENT AREA 488-514 Techwood Drive ( Atlanta Fulton County Georgia

TECHWOOD HOMES, BUILDING 16 HABS No. GA-2257-S TECHWOOD/CLARK HOWELL HOMES REDEVELOPMENT AREA 488-514 Techwood Drive ( Atlanta Fulton County Georgia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Southeast Region Department of the Interior Atlanta, Georgia 30303 rt !\BS ~A ' ~.f ... AT"'L ,4 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY /.t.;OS - TECHWOOD HOMES, BUILDING 16 HABS No. GA-2257-S Location: 488-514 Techwood Drive, NW Atlanta Fulton County Georgia U.S.G.S. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: Northing 3739/560, Easting 741/600 Present Owner: Atlanta Housing Authority 739 West Peachtree Atlanta, Georgia 30365 Present Occupant: Vacant Present Use: Public Housing Techwood/Clark Howell Homes HOPE VI - Urban Revitalization Demonstration (URD) Project To be demolished Significance: Techwood Homes, Building 16 is a contributing building in the Techwood Homes Historic District, nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Techwood Homes is associated with events, agencies, and individuals significant to the history and design of public housing, both nationally and locally. Techwood Homes was the first federally funded public housing project in the United States to reach the construction stage. As the first of 51 "demonstration projects" developed nationwide by the Housing Division of the Public Works Administration (PWA), Techwood·Homes served as an experimental model for interpretation and implementation of design standards established by the Housing Division. The project drew immediate praise for its sturdy construction, fireproof materials, natural lighting and cross-ventilation, ample open space and recreational areas, and community-oriented amenities. Development of this landmark project in Atlanta reflected the planning and lobbying efforts of prominent local citizens. -

The Atlanta Historical Journal

The Atlanta Historical journal Biiekhed UE(fATCKJ„=.._ E<vsf\Poio.<f J Summer/Fall Volume XXVI Number 2-3 The Atlanta Historical Journal Urban Structure, Atlanta Timothy J. Crimmins Dana F. White Guest Editor Guest Editor Ann E. Woodall Editor Map Design by Brian Randall Richard Rothman & Associates Volume XXVI, Numbers 2-3 Summer-Fall 1982 Copyright 1982 by Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. Atlanta, Georgia Cover: The 1895 topographical map of Atlanta and vicinity serves as the background on which railroads and suburbs are highlighted. From the original three railroads of the 1840s evolved the configuration of 1895; since that time, suburban expansion and highway development have dramatically altered the landscape. The layering of Atlanta's metropolitan environment is the focus of this issue. (Courtesy of the Sur veyor General, Department of Archives and History, State of Georgia) Funds for this issue were provided by the Research Division of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Alumni Association of Georgia State University, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the University Research Committee of Emory University. Additional copies of this number may be obtained from the Society at a cost of $7.00 per copy. Please send checks made payable to the Atlanta Historical Society to 3101 Andrews Dr. N.W., Atlanta, Georgia, 30305. TABLE OF CONTENTS Urban Structure, Atlanta: An Introduction By Dana F. White and Timothy J. Crimmins 6 Part I The Atlanta Palimpsest: Stripping Away the Layers of the Past By Timothy J. Crimmins 13 West End: Metamorphosis from Suburban Town to Intown Neighborhood By Timothy J. -

Assessing Urban Tree Canopy in the City of Atlanta; a Baseline Canopy Study

Final Report Assessing Urban Tree Canopy in the City of Atlanta; A Baseline Canopy Study City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Arborist Division Spring 2014 Prepared by: Tony Giarrusso, Associate Director of the Center for GIS, Georgia Institute of Technology Sarah Smith, Research Scientist II, Center for Quality Growth and Regional Development, Georgia Institute of Technology Acknowledgements Project Team: Principal Investigator: Anthony J. Giarrusso, Associate Director, Senior Research Scientist Center for Geographic Information Systems (CGIS) Georgia Institute of Technology 760 Spring Street, Suite 230 Atlanta, GA 30308 Office: 404-894-0127 [email protected] Co-Principal Investigator: Sarah M. Smith, Research Scientist II Center for Quality Growth & Regional Development (CQGRD) 760 Spring Street, Suite 213 Atlanta, GA 30308 Office: 404-385-5133 [email protected] Research Assistants: Amy Atz Gillam Campbell Alexandra Frackelton Anna Harkness Peter Hylton Kait Morano The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the City of Atlanta. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The project team would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals for their assistance on this project. Kathryn A. Evans, Senior Administrative Analyst, Tree Conservation Commission, Department of Planning and Development, Arborist Division Chuck Schultz, Principle Planner, GIS, City of Atlanta Jim Kozak, Davey Resource Group, a Division of the Davey Tree Expert Company - Davey Trees Assessing Urban Tree Cover in the City of Atlanta A Baseline Canopy Study 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... -

Atlanta Georgia “Let’S Go Downtown”

ATLANTA GEORGIA “LET’S GO DOWNTOWN” BY: STEPHEN BINGHAM BARBARA BOGNER SUZANNE C. FREUND Atlanta - Page 1 of 22 1. Introduction In order to assist the Downtown Denver Partnership conduct a peer cities analysis, an assessment of Atlanta, Georgia was conducted. The assessment began by identifying the area of Atlanta that is considered to be the official ‘downtown.’ Research was done of both qualitative and quantitative data. Quantitative geographic and demographic material required minimal analysis to primarily ensuring that data was complete, current, and applicable to the study area. Qualitative data required a more inferential approach. This analysis compelled an advanced understanding of available information in order to establish a knowledge of the current ‘feel’ of the urban center. Once the data was analyzed, a profile for the downtown was established. This profile focused on the current conditions, opportunities and constraints, past successes and failures, as well as current plans and policies of downtown Atlanta and related agencies. After analyzing data and developing a profile for Atlanta, a similar study needed to be conducted for Denver. Utilizing information provided by the Downtown Denver Partnership or found through individual research, a profile for Denver was established that could be used to conduct a comparative analysis between the two cities’ urban centers. The comparative analysis began by identifying similarities and differences between Atlanta and Denver. After a detailed comparison had been completed, several issues of interest were identified. The first type of issues were policies or trends existing in Atlanta that Denver could learn from and perhaps implement in an effort to mitigate current or potential future problems. -

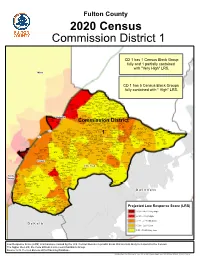

2020 Census Commission District 1

Fulton County 2020 Census Commission District 1 CD 1 has 1 Census Block Group fully and 1 partially contained with "Very High" LRS. Milton CD 1 has 5 Census Block Groups F o rr s y tt h Beacon fully contained with " High" LRS. Wynridge Hill Tidewater Archstone Hillcrest Windward Kendrix Park Greystone Meridian Pointe Admiral Ridge Chasewood Compass Pointe Greatwood Fieldstone Fairways, The Enclave, The Greatwood Windward Ardsley Park Glen Calumet Vicarage, The Place Harbour Creekside Place Harbour Linkside Concord Hall Kensington Oaks Caravelle at Ridge Bent Creek Neighborhoods Walk Laurel Cove Windward Highland Eastgate Of Windward Cove Bay Northshore, Newport Park Phase 2 Pointe Bay Park-Johns Lake The Hartsmill Pointe Creek Eastgate Bluffs Shore Peninsula, Eastgate Spinnakers Woodland Cove Phase 1 The Seven Oaks Phase 3 Landings Stevens Creek Westwind-Alpharetta Northpointe The Gates at North Clipper Bay Leeward Point Phase 2 Shirley Oak Walk Meadows-Johns Estates Southlake Tree Creek Country Cypress Woods Foxhaven Lexington Broadlands Cresslyn Place Point Webb Bridge Thornbury Parc Woods Cambridge Windward-Southpointe Chelsea Walk Crossing (Sub) Nottingham Sterling Park Andover Reserve At Carriage Haynes Park Alpharetta Pennebrooke Gate Wellsley Ashland Woods Forest Park Glen Fox Glen Forest, Wellington, Park Townhomes Stoneridge Windgate Wood Parkside Brenton Estates The Enclave The Windsong Trace Amli at Townhomes-Alpharetta Bridge Manor House at Johns Northwind Braeden Bridge Pointe At Wellington, Standard Park Highlands Creek -

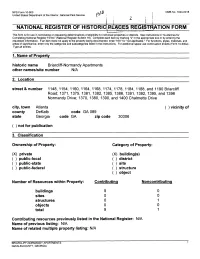

National Register of Historic Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________ historic name Briarcliff-Normandy Apartments other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 1148, 1154, 1160, 1164, 1168, 1174, 1178, 1184, 1188, and 1190 Briarcliff Road; 1371, 1375, 1381, 1382, 1385, 1386, 1391, 1392, 1395, and 1396 Normandy Drive; 1370, 1380, 1390, and 1400 Chalmette Drive city, town Atlanta ( ) vicinity of county DeKalb code GA089 state Georgia code GA zip code 30306 ( ) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: Category of Property: (X) private (X) building(s) ( ) public-local ( ) district ( ) public-state ( ) site ( ) public-federal ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing buildings 9 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 1 objects 0 0 total 9 1 Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: N/A Name of previous listing: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A BRIARCLIFF-NORMANDY APARTMENTS DeKALBCOUNTY, GEORGIA 4. -

FISCAL YEAR 2007 CATALYST IMPLEMENTATION PLAN AHA’S FOUR BUSINESS LINES and CORPORATE SUPPORT

AtlantaAtlanta HousingHousing AuthorityAuthority FiscalFiscal YearYear 20072007 CATALYSTCATALYST ImplementationImplementation PlanPlan “Healthy, mixed-income communities” Board Approved April 26, 2006 Table of Contents Message from the President and Chief Executive Officer Page 1 Message from the Chairman of the AHA Board of Commissioners Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Executive Summary: Overview of AHA’s FY 2007 Implementation Plan Page 7 Part I: Real Estate Management Page 15 Part II: Housing Choice Administration Page 23 Part III: Real Estate Development & Acquisitions Page 32 Part IV: Asset Management Page 40 Part V: Corporate Support Page 44 Conclusion: Measuring Success – MTW Benchmarking Page 49 Appendices Appendix A: MTW Annual Plan Reference Guide Appendix B: AHA’s FY 2007 Corporate Roadmap Appendix C: Implementation of AHA’s CATALYST Plan Appendix D: Public Review and Plan Changes “Healthy Mixed-Income Communities” i Appendix E: Corporate Organization Chart Appendix F: AHA Conventional Public Housing Communities Appendix G: Management Information for Owned/Managed Units and Assisted Units at Mixed-Income Communities Appendix H: Management Information for Leased Housing Appendix I: Candidate Communities for Percentage-Based or Elderly Designation Appendix J: Candidate Communities or Properties for Demolition, Disposition, Voluntary Conversion, Subsidy Conversion and/or Other Repositioning Appendix K: Mixed-income Communities Appendix L: Statement of Corporate Policies Appendix M: Housing Choice Administrative Plan Appendix N: MTW