Atlanta Housing 1944 to 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta Neighborhoods Reap

Vol. 4, Issue 2 | 1st Quarter 2011 BEACHAM Your Monthly Market Update From 3284 Northside Parkway The Best People in Atlanta Real Estate™ Suite 100 Atlanta, GA 30327 404.261.6300 Insider www.beacham.com Home sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta What’s neighborhoods reap the benefits of an early spring Hot The luxury market. There he spring selling season came early for many intown real estate markets like Buckhead and the were 13 sales homes in metro Atlanta priced neighborhoods in Buckhead and what is rest of the Atlanta are varied according to Carver. $2 million or more in considered “In-town Atlanta” (Ansley Park, East First and foremost, Buckhead is a top housing draw T the first quarter (11 in Buckhead, Midtown, Morningside, Virginia-Highlands), in any market because of its proximity to the city’s Buckhead, 2 in East Cobb), where single family home sales collectively rose 21% greatest concentration of exceptional homes, high a 63% increase from from the first quarter of 2010 and prices increased 6%. paying jobs, shopping, restaurants, schools, etc. the first quarter a year The story was not as rosy for the rest In March, more than With an average home sale price ago. However, sales are of metro Atlanta, however. While single of $809,275 in the first quarter, still 32% below the first family home sales were up 5% in the first 15% of our new listings Buckhead is an affluent community quarter of 2007 when the quarter, prices were down 8% from a year went under contract and the affluent have emerged luxury market was peaking. -

Vitra Accessories Collection Developed by Vitra in Switzerland Update: Maison & Objet, September 2017

Vitra Accessories Collection Developed by Vitra in Switzerland Update: Maison & Objet, September 2017 The Vitra Accessories Collection encompasses the growing portfolio of design objects, accessories and textiles produced by the Swiss furniture company. The collection is based on classic patterns and objects conceived by designers such as Alexander Girard, Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson. In addition to these classics, it also includes pieces by contemporary designers like Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, Jasper Morrison, Hella Jongerius and Michel Charlot. Authenticity, joy and playfulness are hallmarks of the Vitra Accessories Collection. For the autumn / winter collection of 2017 Vitra will expand its accessories portfolio with design objects by Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard and George Nelson. Charles & Ray Eames Charles and Ray Eames are among the most influential designers of the twentieth century. Working with tireless enthusiasm, the pair explored the fields of photography, film, architecture, exhibitions, and furniture and product design, making landmark contributions in each domain. Plywood Elephant & Eames Elephant (small), 1945 In the 1940s, Charles and Ray Eames spent several years developing and refining a technique for the three-dimensional moulding of plywood, creating a series of furniture items and sculptures in the process. Among these initial designs, the two-part elephant proved to be the most technically challenging due to its tight compound curves, and the piece never went into serial production. A prototype was given to Charles's 14-year-old daughter Lucia Eames and later borrowed for the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946. It still survives in the Eames family archives today. -

Buyer Resource Guide

Buyer Resource Guide New or Returning Buyer? Use this guide as a quick overview of everything you need to know to get started sourcing. BRIGHTON SARO CREATIVE CO-OP SURYA Campus Guide Navigating Campus BuildingBuilding 1 AmericasMart’s campus expands over three integrated buildings connected by bridges. To find product, use 23 AMC Ofces the AmericasMart app, AmericasMart website, 22 AMC Ofces or see floor plans at every elevator bank to locate 21 AMC Ofces showrooms, temporaries and bridges. 20 Holiday & Floral / Home Décor T During January and July Markets, tradeshow halls 19 Holiday & Floral / Home Décor BuildingBuilding 2 in Buildings 1, 2 and 3 feature temporary exhibitors. 18 Holiday & Floral / Home Décor BRIDGE 18 Gift Atlanta Apparel (Building 3 only) also offers 17 Holiday & Floral / Home Décor BRIDGE 17 Gift temporaries during their markets. 16 Holiday & Floral / Home Décor BRIDGE 16 Gift 15 Home & Design BRIDGE 15 Gift BuildingBuilding 3 14 Home & Design BRIDGE 14 Gift Building 2 15 Penthouse Theatre 13 Home / Furniture BRIDGE 13 Gift & Home BRIDGE 14 Prom / Bridal / Social Occasion 12 Home / Furniture BRIDGE 12 Gift & Home BRIDGE 13 Children’s World 11 Home / Furniture BRIDGE 11 Gift & Home 12 Prom / Bridal / Social Occasion 10 Home / Furniture / Linens BRIDGE 10 Gift & Home The Gardens® BRIDGE 11 Women’s Apparel 9 Home / Furniture / Linens BRIDGE 9 Tabletop & Gift The Gardens® BRIDGE 10 Prom / Bridal / Social Occasion 8 Meeting Space 8 Tabletop & Gift Gourmet & Housewares BRIDGE 9 Women’s Apparel 7 T Tradeshow Hall BRIDGE -

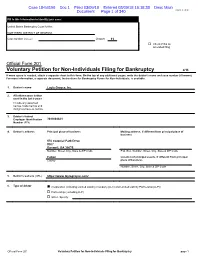

Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, Is Available

Case 18-54196 Doc 1 Filed 03/09/18 Entered 03/09/18 16:18:38 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 340 3/09/18 4:13PM Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA Case number (if known) Chapter 11 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 4/16 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name Layla Grayce, Inc. 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed names, trade names and doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 30-0464821 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 570 Colonial Park Drive #307 Roswell, GA 30075 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Fulton Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) https://www.laylagrayce.com/ 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy page 1 Case 18-54196 Doc 1 Filed 03/09/18 Entered 03/09/18 16:18:38 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 340 3/09/18 4:13PM Debtor Layla Grayce, Inc. -

Colony Square, 1175 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta, Georgia

Colony Square, 1175 Peachtree Street NE, Atlanta, Georgia View this office online at: https://www.newofficeamerica.com/details/serviced-offices-colony-square-117 5-peachtree-street-ne-atlanta-georgia With remarkable views over this prominent part of Atlanta and 3 floors of both co-working and private office space, this serviced business center is great place to start your office hunt . Tenants at the center benefit from ultimate convenience thanks to the 24 hour-a-day access policy, which guarantees use of office spaces is always preserved in a secure and reliable fashion whenever it is needed. Amenities include admittance to a comfortable lounge area, which ensures all tenants are able to relax during their breaks and go back to their desks refreshed and more productive - it even comes with fruit infused water and micro-roasted coffee on tap! Transport links Nearest road: Nearest airport: Key features 24 hour access Administrative support Comfortable lounge Conference rooms Disabled facilities (DDA/ADA compliant) Double glazing Furnished workspaces High-speed internet Hot desking IT support available Kitchen facilities Lift Meeting rooms Office cleaning service Photocopying available Postal facilities/mail handling Reception staff Town centre location WC (separate male & female) Wireless networking Location Positioned on the Peachtree Street interchange, amidst numerous art galleries, parks and local landmarks, this center is rising up the ranks as one of Atlanta's favorite office space providers. This location is well suited for traveling business people due to the fact it is only 18 minutes drive (via the I-75S) to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport. The fusion of these factors have helped to ensure that this office package at Colony Square has an unparalleled approval rating amongst it's tenants and is suitable for companies of all shapes and sizes. -

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT US29 Atlanta Vicinity Fulton County

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS GA-2390 US29 GA-2390 Atlanta vicinity Fulton County Georgia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS No. GA-2390 Location: Situated between the City of Atlanta, Decatur, and Emory University in the northeast Atlanta metropolitan area, DeKalb County. Present Owner: Multiple ownership. Present Occupant: Multiple occupants. Present Use: Residential, Park and Recreation. Significance: Druid Hills is historically significant primarily in the areas of landscape architecture~ architecture, and conununity planning. Druid Hills is the finest examp1e of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century comprehensive suburban planning and development in the Atlanta metropo 1 i tan area, and one of the finest turn-of-the-century suburbs in the southeastern United States. Druid Hills is more specifically noted because: Cl} it is a major work by the eminent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and Ms successors, the Olmsted Brothers, and the only such work in Atlanta; (2) it is a good example of Frederick Law Olmsted 1 s principles and practices regarding suburban development; (3) its overall planning, as conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted and more fully developed by the Olmsted Brothers, is of exceptionally high quality when measured against the prevailing standards for turn-of-the-century suburbs; (4) its landscaping, also designed originally by Frederick Law Olmsted and developed more fully by the Olmsted Brothers, is, like its planning, of exceptionally high quality; (5) its actual development, as carried out oripinally by Joel Hurt's Kirkwood Land Company and later by Asa G. -

The Granite Mansion: Georgia's Governor's Mansion 1924-1967

The Granite Mansion: Georgia’s Governor’s Mansion 1924-1967 Documentation for the proposed Georgia Historical Marker to be installed on the north side of the road by the site of the former 205 The Prado, Ansley Park, Atlanta, Georgia June 2, 2016 Atlanta Preservation & Planning Services, LLC Georgia Historical Marker Documentation Page 1. Proposed marker text 3 2. History 4 3. Appendices 10 4. Bibliography 25 5. Supporting images 29 6. Atlanta map section and photos of proposed marker site 31 2 Proposed marker text: The Granite Governor’s Mansion The Granite Mansion served as Georgia’s third Executive Mansion from 1924-1967. Designed by architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, the house at 205 The Prado was built in 1910 from locally- quarried granite in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. It was first home to real estate developer Edwin P. Ansley, founder of Ansley Park, Atlanta’s first automobile suburb. Ellis Arnall, one of the state’s most progressive governors, resided there (1943-47). He was a disputant in the infamous “three governors controversy.” For forty-three years, the mansion was home to twelve governors, until poor maintenance made it nearly uninhabitable. A new governor’s mansion was constructed on West Paces Ferry Road. The granite mansion was razed in 1969, but its garage was converted to a residence. 3 Historical Documentation of the Granite Mansion Edwin P. Ansley Edwin Percival Ansley (see Appendix 1) was born in Augusta, GA, on March 30, 1866. In 1871, the family moved to the Atlanta area. Edwin studied law at the University of Georgia, and was an attorney in the Atlanta law firm Calhoun, King & Spalding. -

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF of RETAIL AVAILABLE

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF OF RETAIL AVAILABLE LOCATED IN THE HEART OF 12TH AND MIDTOWN A premier apartment high rise building with a WELL POSITIONED RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Surrounded by Atlanta’s Highly affluent market, with Restaurant and retail vibrant commercial area median annual household opportunities available incomes over $74,801, and median net worth 330 Luxury apartment 596,000 SF Building $58 Million Project units. 476 parking spaces SITE PLAN - PHASE 4A / SUITE 3 / 1,861 SF* SITE PLAN 12th S TREET SUITERETAIL 1 RETAIL SUITERETAIL 3 RESIDENTIAL RETAIL RETAIL 1 2 3 LOBBY 4 5 2,423 SF 1,8611,861 SFSF SUITERETAIL 6A 3,6146 A SF Do Not Distrub Tenant E VENU RETAIL A 6 B SERVICE LOADING S C E N T DOCK SUITERETAIL 7 E 3,622 7 SF RETAIL PARKING CR COMPONENT N S I T E P L AN O F T H E RET AIL COMP ONENT ( P H ASE 4 A @ 77 12T H S TREE T ) COME JOIN THE AREA’S 1 2 TGREATH & MID OPERATORS:T O W N C 2013 THIS DRAWING IS THE PROPERTY OF RULE JOY TRAMMELL + RUBIO, LLC. ARCHITECTURE + INTERIOR DESIGN AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT A TLANT A, GEOR G I A COMMISSI O N N O . 08-028.01 M A Y 28, 2 0 1 3 L:\06-040.01 12th & Midtown Master Plan\PRESENTATION\2011-03-08 Leasing Master Plan *All square footages are approximate until verified. THE MIDTOWN MARKET OVERVIEW A Mecca for INSPIRING THE CREATIVE CLASS and a Nexus for TECHNOLOGY + INNOVATION MORE THAN ONLY 3 BLOCKS AWAY FROM 3,000 EVENTS ANNUALLY PIEDMONT PARK • Atlanta Dogwood Festival, • Festival Peachtree Latino THAT BRING IN an arts and crafts fair • Music Midtown & • The finish line of the Peachtree Music Festival Peachtree Road Race • Atlanta Pride Festival & 6.5M VISITORS • Atlanta Arts Festival Out on Film 8 OF 10 ATLANTA’S “HEART OF THE ARTS”DISTRICT ATLANTA’S LARGEST LAW FIRMS • High Museum • ASO • Woodruff Arts Center • Atlanta Ballet 74% • MODA • Alliance Theater HOLD A BACHELORS DEGREE • SCAD Theater • Botanical Gardens SURROUNDED BY ATLANTA’S TOP EMPLOYERS R. -

After Seven Decades Strong, Good Design Continues Its Iconic History Awarding the Best and Most Recognized Design Products Worldwide

MORE INFORMATION Jennifer Nyholm Chicago, Illinois USA [email protected] EUROPE CONTACTS: Fachanan Conlon Dublin, Ireland [email protected] AFTER SEVEN DECADES STRONG, GOOD DESIGN CONTINUES ITS ICONIC HISTORY AWARDING THE BEST AND MOST RECOGNIZED DESIGN PRODUCTS WORLDWIDE The Modern Design Revolution Persists in a Steady Loud and Showy Innovative Pace as It Did at the Offset of the 1950s. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS (MAY 25, 2020) — Seventy years ago, a group of die-hard advocates for modern design banded together to brand a novel marketing campaign to showcase and trumpet new American home furnishings, household items, and industrial objects with a revolutionary passion and zeal. Good Design® was founded in Chicago in 1950 by architects Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., director of the Industrial Design Department, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and professor of Architecture and Art History at Columbia University with the first installation of Good Design at The Merchandise Mart in Chicago. The first Good Design exhibition was sponsored by The Merchandise Mart and The Museum of Modern Art, together with the Society of Industrial Designers, the American Institute of Decorators, the Home Furnishing Industry Committee, Neiman-Marcus, Lord & Taylor, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the American Institute of Architects. The Good Design exhibition opened at The Merchandise Mart on January 16, 1950 with the installation designed by Charles and Ray Eames. A reduced version of the exhibition, assembled by Eames, opened at MoMA in New York on November 21, 1950. This was the first time that a wholesale merchandising center and an art museum joined forces to present “the best new examples in modern design in home furnishings.” The program called for three shows a year: one during the Chicago winter furniture market in January, another coinciding with the June summer market in Chicago, and a November show in New York based on the previous two exhibitions. -

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary ................................................................5 Summary of Resources ...........................................................6 Regionally Important Resources Map ................................12 Introduction ...........................................................................13 Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value .................21 Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ..................................48 Areas of Scenic and Agricultural Value ..............................79 Appendix Cover Photo: Sope Creek Ruins - Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area/ Credit: ARC Tables Table 1: Regionally Important Resources Value Matrix ..19 Table 2: Regionally Important Resources Vulnerability Matrix ......................................................................................20 Table 3: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ...........46 Table 4: General Policies and Protection Measures for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ................47 Table 5: National Register of Historic Places Districts Listed by County ....................................................................54 Table 6: National Register of Historic Places Individually Listed by County ....................................................................57 Table 7: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ............................77 Table 8: General Policies -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

THE Inman Park

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association November 2015 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 43 • Issue 11 Coming Soon BY DENNIS MOBLEY • [email protected] Inman Park Holiday Party I’m pr obably showing my Friday,2015 December 11 • 7:30 pm – 11:00 pm age, but I can remember the phrase “coming soon to a The Trolley Barn • 963 Edgewood Avenue theater near you” like it was yesterday. In this case, I The annual Inman Park Holiday Party returns wanted to give our readers a heads-up as to what they can to The Trolley Barn this year. Don’t miss this expect with our conversion to chance to meet and visit with fellow Inman President’s Message the MemberClicks-powered Park neighborsHoliday over food, drinks Party and dancing. IPNA website and associated membership management software. Enjoy heavy hors d’oeuvres catered by Stone By the time you read this November issue of the Advocator, some Soup and complimentaryAnnouncement beer and wine. A 400+ of you will have received an email from our Vice President DJ will be there to spin a delightful mix of old of Communications, James McManus, notifying you that you standards and newMissing favorites. So don your are believed to be a current IPNA member in good standing. (We holiday fi nest and join us for a good time! gleaned this list of 400+ from our current database and believe it to be fairly accurate).