Toronto's Waterfront at War, 191 4-1 91 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Description of the Potentially Affected Environment

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 3. Description of the Potentially Affected Environment The purpose of Chapter 3 is to present an overview of the environment potentially affected by the SWP to create familiarity with issues to be addressed and the complexity of the environment likely to be affected by the Project. All aspects of the environment within the Project Study Area (see Figure 2- 1 in Chapter 2) relevant to the Project and its potential effects have been described in this chapter. The chapter is divided into three sections which capture different components of the environment: 1. Physical environment: describes the coastal and geotechnical processes acting on the Project Study Area; 2. Natural environment: describes terrestrial and aquatic habitat and species; and, 3. Socio-economic environment: describes existing and planned land use, land ownership, recreation, archaeology, cultural heritage, and Aboriginal interests. The description of the existing environment is based on the information from a number of studies, which have been referenced in the relevant sections. Additional field surveys were undertaken where appropriate. Where applicable, future environmental conditions are also discussed. For most components of the environment, existing conditions within the Project Area or Project Study Area are described. Where appropriate, conditions within the broader Regional Study Area are also described. 3.1 Physical Environment Structures and property within slopes, valleys and shorelines may be susceptible to damage from natural processes such as erosion, slope failures and dynamic beaches. These processes become natural hazards when people and property locate in areas where they normally occur (MNR, 2001). Therefore, understanding physical natural processes is vital to developing locally-appropriate Alternatives in order to meet Project Objectives. -

3131 Lower Don River West Lower Don River West 4.0 DESCRIPTION

Lower Don River West Environmental Study Report Remedial Flood Protection Project 4.0 DESCRIPTION OF LOWER DON 4.1 The Don River Watershed The Don River is one of more than sixty rivers and streams flowing south from the Oak Ridges Moraine. The River is approximately 38 km long and outlets into the Keating Channel, which then conveys the flows into Toronto Harbour and Lake Historic Watershed Ontario. The entire drainage basin of the Don urbanization of the river's headwaters in York River is 360 km2. Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.2, on the Region began in the early 1980s and continues following pages, describe the existing and future today. land use conditions within the Don River Watershed. Hydrologic changes in the watershed began when settlers converted the forests to agricultural fields; For 200 years, the Don Watershed has been many streams were denuded even of bank side subject to intense pressures from human vegetation. Urban development then intensified settlement. These have fragmented the river the problems of warmer water temperatures, valley's natural branching pattern; degraded and erosion, and water pollution. Over the years often destroyed its once rich aquatic and during the three waves of urban expansion, the terrestrial wildlife habitat; and polluted its waters Don River mouth, originally an extensive delta with raw sewage, industrial/agricultural marsh, was filled in and the lower portion of the chemicals, metals and other assorted river was straightened. contaminants. Small Don River tributaries were piped and Land clearing, settlement, and urbanization have buried, wetlands were "reclaimed," and springs proceeded in three waves in the Don River were lost. -

Volume 5 Has Been Updated to Reflect the Specific Additions/Revisions Outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, Dated November, 2017

DISCLAIMER AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY This Revised Final Environmental Project Report – Volume 5 has been updated to reflect the specific additions/revisions outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, dated November, 2017. As such, it supersedes the previous Final version dated October, 2017. The report dated October, 2017 (“Report”), which includes its text, tables, figures and appendices) has been prepared by Gannett Fleming Canada ULC (“Gannett Fleming”) and Morrison Hershfield Limited (“Morrison Hershfield”) (“Consultants”) for the exclusive use of Metrolinx. Consultants disclaim any liability or responsibility to any person or party other than Metrolinx for loss, damage, expense, fines, costs or penalties arising from or in connection with the Report or its use or reliance on any information, opinion, advice, conclusion or recommendation contained in it. To the extent permitted by law, Consultants also excludes all implied or statutory warranties and conditions. In preparing the Report, the Consultants have relied in good faith on information provided by third party agencies, individuals and companies as noted in the Report. The Consultants have assumed that this information is factual and accurate and has not independently verified such information except as required by the standard of care. The Consultants accept no responsibility or liability for errors or omissions that are the result of any deficiencies in such information. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are valid as of the date of the Report and are based on the data and information collected by the Consultants during their investigations as set out in the Report. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are based on the conditions encountered by the Consultants at the site(s) at the time of their investigations, supplemented by historical information and data obtained as described in the Report. -

The Politicization of the Scarborough Rapid Transit Line in Post-Suburban Toronto

THE ‘TOONERVILLE TROLLEY’: THE POLITICIZATION OF THE SCARBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT LINE IN POST-SUBURBAN TORONTO Peter Voltsinis 1 “The world is watching.”1 A spokesperson for the Province of Ontario’s (the Province) Urban Transportation Development Corporation (UTDC) uttered those poignant words on March 21, 1985, one day before the Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) inaugural opening of the Scarborough Rapid Transit (SRT) line.2 One day later, Ontario Deputy Premier Robert Welch gave the signal to the TTC dispatchers to send the line’s first trains into the Scarborough Town Centre Station, proclaiming that it was “a great day for Scarborough and a great day for public transit.”3 For him, the SRT was proof that Ontario can challenge the world.4 This research essay outlines the development of the SRT to carve out an accurate place for the infrastructure project in Toronto’s planning history. I focus on the SRT’s development chronology, from the moment of the Spadina Expressway’s cancellation in 1971 to the opening of the line in 1985. Correctly classifying what the SRT represents in Toronto’s planning history requires a clear vision of how the project emerged. To create that image, I first situate my research within Toronto’s dominant historiographical planning narratives. I then synthesize the processes and phenomena, specifically postmodern planning and post-suburbanization, that generated public transit alternatives to expressway development in Toronto in the 1970s. Building on my synthesis, I present how the SRT fits into that context and analyze the changing landscape of Toronto land-use politics in the 1970s and early-1980s. -

James T. Lemon Fonds

University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services James T. Lemon Fonds Prepared by: Marnee Gamble Nov. 1995 Revised Nov. 2005 Revised Nov 2016 © University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE…………………………………………………………………………1 SCOPE AND CONTENT………………………………………………………………………...2 Series 1 Biographical……………………………………………………………………….3 Series 2 Correspondence…………………………………………………………………...3 Series 3 Conferences and speaking engagements…………………………………………...4 Series 4 Publishing Activities………………………………………………………………4 Series 5 Reviews…………………………………………………………………………...5 Series 6 Research Grants…………………………………………………………………..5 Series 7 Teaching Files……………………………………………………………………..5 Series 8 Student Files………………………………………………………………………6 Series 9 References………………………………………………………………………...6 Series 10 Department of Geography………………………………………………………..7 Series 11 University of Toronto…………………………………………………………….7 Series 12 Professional Associations and Community Groups………………………………8 Series 13 New Democratic Party…………………………………………………………...8 Series 14 Christian Youth Groups………………………………………………………….8 Series 15 Family Papers…………………………………………………………………….9 Appendix 1 Series 12: Professional Associations and Community Groups 10 Appendix 2 Series 7 : Teaching student essays B1984-0027, B1986-0015, B1988-0054 12 University of Toronto Archives James T. Lemon Fonds BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Raised in West Lorne, Ontario, James (Jim) Thomas Lemon attended the University of Western Ontario where he received his Bachelor of Arts in Geography (1955). He later attended the University of Wisconsin where he received a Master of Science in Geography (1961) as well as his Ph.D. (1964). In 1967, after having worked as an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Prof. Lemon joined the University of Toronto Geography Department, where he remained until his retirement in 1994. His career has been spent in the field of urban historical geography of which he has written numerous articles, papers and chapters in books. -

Peer Review EA Study Design Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport BBTCA

Imagine the result Peer Review – EA Study Design Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport (BBTCA) Runway Expansion and Introduction of Jet Aircraft Final Report August 2015 BBTCA Peer Review of EA Study Design Report ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 Background 1-1 1.2 Current Assignment 1-3 2.0 PEER REVIEW APPROACH 2-1 2.1 Methodology 2-1 3.0 FINDINGS OF PEER REVIEW OF AECOM’S DRAFT STUDY DESIGN REPORT 3-1 3.1 EA Process and Legislation 3-1 3.2 Public Consultation & Stakeholder Engagement 3-1 3.3 Air Quality 3-2 3.4 Public Health 3-5 3.5 Noise 3-6 3.6 Natural Environment 3-10 3.7 Socio-Economic Conditions 3-11 3.8 Land Use & Built Form 3-14 3.9 Marine Physical Conditions and Water Quality 3-15 3.10 Transportation 3-15 3.11 Archaeology & Cultural Heritage 3-18 4.0 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS 4-1 APPENDIX A Presentation Given to the Working Group (22 June 2015) B Presentation of Draft Phase I Peer Review Report Results (13 July 2015) i BBTCA Peer Review of EA Study Design Report ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AERMOD Atmospheric Dispersion Modelling System ARCADIS ARCADIS Canada Inc. BBTCA Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport CALPUFF Meteorological and Air Quality Monitoring System CCG Canadian Coast Guard CEAA Canadian Environmental Assessment Act CO Carbon Monoxide COPA Canadian Owners and Pilots Association dBA Decibel Values of Sounds EA Environmental Assessment EC Environment Canada GBE Government Business Enterprise GWC Greater Waterfront Coalition HEAT Habitat and Environmental Assessment Tool INM Integrated Noise Model Ldn Day-Night -

The Fish Communities of the Toronto Waterfront: Summary and Assessment 1989 - 2005

THE FISH COMMUNITIES OF THE TORONTO WATERFRONT: SUMMARY AND ASSESSMENT 1989 - 2005 SEPTEMBER 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank the many technical staff, past and present, of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority and Ministry of Natural Resources who diligently collected electrofishing data for the past 16 years. The completion of this report was aided by the Canada Ontario Agreement (COA). 1 Jason P. Dietrich, 1 Allison M. Hennyey, 1 Rick Portiss, 1 Gord MacPherson, 1 Kelly Montgomery and 2 Bruce J. Morrison 1 Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, 5 Shoreham Drive, Downsview, ON, M3N 1S4, Canada 2 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Lake Ontario Fisheries Management Unit, Glenora Fisheries Station, Picton, ON, K0K 2T0, Canada © Toronto and Region Conservation 2008 ABSTRACT Fish community metrics collected for 16 years (1989 — 2005), using standardized electrofishing methods, throughout the greater Toronto region waterfront, were analyzed to ascertain the current state of the fish community with respect to past conditions. Results that continue to indicate a degraded or further degrading environment include an overall reduction in fish abundance, a high composition of benthivores, an increase in invasive species, an increase in generalist species biomass, yet a decrease in specialist species biomass, and a decrease in cool water Electrofishing in the Toronto Harbour thermal guild species biomass in embayments. Results that may indicate a change in a positive community health direction include no significant changes to species richness, a marked increase in diversity in embayments, a decline in non-native species in embayments and open coasts (despite the invasion of round goby), a recent increase in native species biomass, fluctuating native piscivore dynamics, increased walleye abundance, and a reduction in the proportion of degradation tolerant species. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual Report 2017 Investing Today for Tomorrow AVAILABLE IN THESE FORMATS PRINT WEBSITE MOBILE © Toronto Port Authority 2018. All rights reserved. To obtain additional copies of this report please contact: 60 Harbour Street, Toronto, ON M5J 1B7 Canada PortsToronto The Toronto Port Authority, doing business as Communications and Public Affairs Department PortsToronto since January 2015, is a government 60 Harbour Street business enterprise operating pursuant to the Toronto, Ontario, M5J 1B7 Canada Marine Act and Letters Patent issued by Canada the federal Minister of Transport. The Toronto Port Phone: 416 863 2075 Authority is hereafter referred to as PortsToronto. E-mail: [email protected] 2 PortsToronto | Annual Report 2017 Table of Contents About PortsToronto 4 Mission and Vision 5 Message from the Chair 6 Message from the Chief Executive Officer 8 Corporate Governance 12 Business Overview Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport 14 Port of Toronto 18 Outer Harbour Marina 22 Real Estate and Property Holdings 24 Four Pillars 26 City Building 27 Community Engagement 30 Environmental Stewardship 40 Financial Sustainability 44 Statement of Revenue and Expenses 45 Celebrating 225 years of port activity 46 About PortsToronto The Toronto Port Authority, doing business as and hereinafter referred to as PortsToronto, is a federal government business enterprise that owns and operates Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport, Marine Terminal 52 within the Port of Toronto, the Outer Harbour Marina and various properties along Toronto’s waterfront. Responsible for the safety and efficiency of marine navigation in the Toronto Harbour, PortsToronto also exercises regulatory control and public works services for the area, works with partner organizations to keep the Toronto Harbour clean, issues permits to recreational boaters and co-manages the Leslie Street Spit site with partner agency the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority on behalf of the provincial Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. -

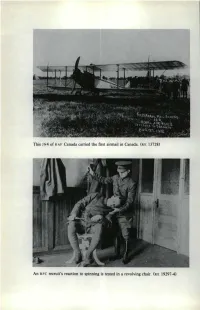

(RE 13728) an RFC Recruit's Reaction to Spinning Is Tested in a Re

This J N4 of RAF Canada carried the first ainnail in Canada. (R E 13728) An RFC recruit's reaction to spinning is tested in a revolving chair. (RE 19297-4) Artillery co-operation instruction RFC Canada scheme. The diagrams on the blackboard illustrate techniQues of rang.ing. (RE 64-507) Brig.-Gen. Cuthbert Hoare (centre) with his Air Staff. On the right is Lt-Col. A.K. Tylee of Lennox ville, Que., responsible for general supervision of training. Tylee was briefly acting commander of RAF Canada in 1919 before being appointed Air Officer Commanding the short-lived postwar CAF in 1920. (RE 64-524) Instruction in the intricacies of the magneto and engine ignition was given on wingless (and sometimes tailless) machines known as 'penguins.' (AH 518) An RFC Canada barrack room (RE 19061-3) Camp Borden was the first of the flying training wings to become fully organized. Hangars from those days still stand, at least one of them being designated a 'heritage building.' (RE 19070-13) JN4 trainers of RFC Canada, at one of the Texas fields in the winter of I 917-18 (R E 20607-3) 'Not a good landing!' A JN4 entangled in Oshawa's telephone system, 22 April 1918 (RE 64-3217) Members of HQ staff, RAF Canada, at the University of Toronto, which housed the School of Military Aeronautics. (RE 64-523) RFC cadets on their way from Toronto to Texas in October 1917. Canadian winters, it was believed, would prevent or drastically reduce flying training. (RE 20947) JN4s on skis devised by Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd, probably in February 1918. -

Heritage Property Nomination Form 2018

HERITAGE PRESERVATION SERVICES Heritage Property Nomination Form Please complete this form. Attach additional pages as necessary. A. Address/Name of Property Nominated: Area (boundaries): Ward No.: To find the ward number: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/council/members-of-council/ Map: Please attach an extract from a street map, marking the individual property, properties, street or area being nominated B. Please check one box. Nominated for: Listing on Inventory Designation under OHA C. Name of Nominator: Address of Nominator: 1 1. Reason for Nomination: I am nominating this property/group of properties/area because: The property is part of a group and I believe this group stands out because: 2. Classification (for each property): Building Type: (i.e., house, church, store, warehouse, etc.) Other: (outbuilding, landscape feature, etc.) Current Use: (residential, commercial, etc.) 2 3. Description (for each property): Photograph: Please attach 4x6" colour photographs showing (1) the street elevation and other applicable views for each property and (2) a group shot if the property is part of a group. Historical Name: Date of Construction: Architect/Builder/Contractor: Original Use: Significant Persons/Events: Alterations: 4. Sources: Please indicate whether you have consulted the following sources; please attach research information and full references (list of archives/libraries attached): __ Land Records (Land Registry Office) __ City Directories __ Goad's Fire Insurance Maps __ Building Permits __ Historical Photographs __ -

Seaway Compass, Spring 2018

SeawayCompass U.S. Department of Transportation • Saint Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation SPRING 2018 www.greatlakes-seaway.com | Facebook: www.fb.com/usdotslsdc SLSDC Great Lakes Regional Initiative Continues into Third Year The SLSDC has been better able to support Great Lakes ports, terminals, shippers, carriers, and labor to increase maritime trade. With the recent arrival of Ken Carey, the Canadian St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation’s Manager of Market Development, the two Seaway Corporations are continuing to expand and grow the Seaway maritime supply chain. Outreach to new and existing customers and stakeholders remains a priority. Recent examples of these efforts include: • Promoting Great Lakes ports at the Traffic Club of Chicago and North American Rail Shippers Association (NARS) Annual Meeting in Chicago (May 2018); • Representing the Seaway System at the 2018 AWEA Windpower Conference in Chicago (May 2018); • Co-exhibiting with the Port of Milwaukee at the 2018 Wisconsin International Trade Conference (May 2018); • Sustaining the Hwy H2O Houston freight forwarder and supply chain initiative in Texas while also seeking new customers for the System in the energy sector at the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) in May 2018; • Representing the Seaway Corporations at the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Governors & Premiers’ second Maritime Day in Ottawa, Ontario (April 2018); • Identifying new Seaway customers as part of the Hwy H2O initiative on U.S. grain at the National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA) Annual Meeting in Phoenix (March 2018) and the U.S. Grains Council Annual Meeting in Houston (February 2018); CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 DEPUTY ADMINISTRATOR’S GUEST COLUMNIST ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: COLUMN David Naftzger St. -

Toronto Port Authority Management's Discussion And

TORONTO PORT AUTHORITY (Doing Business as PortsToronto) MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS – 2019 (In thousands of dollars) May 27, 2020 Management's discussion and analysis (MD&A) is intended to assist in the understanding and assessment of the trends and significant changes in the results of operations and financial condition of the Toronto Port Authority, doing business as PortsToronto (the “Port Authority”) for the years ended December 31, 2019 and 2018 and should be read in conjunction with the 2019 Audited Financial Statements (the “Financial Statements”) and accompanying notes. All dollar amounts in this MD&A are in thousands of dollars, except investments on community initiatives (page 2), economic activity at the Port of Toronto (page 2) and AIF rates per passenger (pages 3 and 6). Summary The Port Authority continued to be profitable in 2019. Net Income for the year was $3,531, slightly up from $3,525 in 2018. This MD&A will discuss the reasons for changes in Net Income year over year, as well as highlight other areas affecting the Port Authority’s financial performance in 2019. The Port Authority presents its financial statements under International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). The accounting policies set out in Note 2 of the Financial Statements have been applied in preparing the Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2019, and in the comparative information presented in these Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2018. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on PortsToronto In March 2020, a global pandemic, referred to as COVID-19, was confirmed and a public health emergency was declared.