Bernard Hoose - Proportionalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II's Theology of the Body

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-6-2016 Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II’s Theology of the Body: An Analysis of the Historical Development of Doctrine in the Catholic Tradition John Segun Odeyemi Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Odeyemi, J. (2016). Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II’s Theology of the Body: An Analysis of the Historical Development of Doctrine in the Catholic Tradition (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1548 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. UNDERSTANDING HUMAN SEXUALITY IN JOHN PAUL II’S THEOLOGY OF THE BODY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CATHOLIC TRADITION. A Dissertation Submitted to Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By John Segun Odeyemi May 2016 Copyright by John Segun Odeyemi 2016 UNDERSTANDING HUMAN SEXUALITY IN JOHN PAUL II’S THEOLOGY OF THE BODY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CATHOLIC TRADITION. By John Segun Odeyemi Approved on March 31, 2016 _______________________________ __________________________ Prof. George S. Worgul Jr. S.T.D., Ph.D. Dr. Elizabeth Cochran Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Rev. Dr. Gregory I. Olikenyen C.S.Sp. Dr. James Swindal Assistant Professor of Theology Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate (Committee Member) School of Liberal Arts iii DEDICATION In honor of my dearly beloved parents on the 50th anniversary of their marriage, (October 30th, 1965 – October 30th 2015) Richard Tunji and Agnes Morolayo Odeyemi. -

Reinhold Niebuhr, Christian Realism, and Just War Theory a Critique

pal-patterson-003 10/24/07 10:23 AM Page 53 CHAPTER 3 Reinhold Niebuhr, Christian Realism, and Just War Theory A Critique Keith Pavlischek his chapter examines how Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christian realism departs in fundamental and profound ways from the classical just war Ttradition and explains why this matters. In short, Niebuhrian realism proceeds from a liberal theology that rejects much of the theological and philosophical orthodoxy associated with the broad natural law tradition and its progeny just war theory, resulting in a worldview far different from that of early “Christian realists” like Augustine and Aquinas. For brevity’s sake, this paper defines “classical” or “traditional” just war theory as a theological-philosophical trajectory that runs from Ambrose and Augustine through medieval developments summarized by Aquinas, then reaffirmed by Calvin and the early modern just war theorists, such as Grotius, Vitoria, and Suarez. Contemporary proponents of classical just war theory include Paul Ramsey (who revived the tradition among Protestants following World War II), James Turner Johnson (Ramsey’s student), Oliver O’Donovan, George Weigel, and more recently Darrell Cole. An obvious question is whether this classical just war tradition, contrasted here against Niebuhr’s Christian realism, is not also a form of Christian realism. The answer is “yes.” Few would object to classifying two millennia of reflection as broadly “Christian realist” if what is meant is “not pacifist,” if it takes seri- ously the Christian doctrine of original sin, and if it declares the inevitable influence of human fallenness in political life and international affairs. Indeed, pal-patterson-003 10/24/07 10:23 AM Page 54 54 Keith Pavlischek Niebuhrian realism shares with older Christian realisms—notably the just war tradition—concerns about power, justice, and the law of love in this world. -

Why Does It Matter?" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Prudential Personalism" > Why Does It Matter?

HONORING FR. O'ROURKE What Is "Prudential Personalism" > Why Does It Matter? Fr. O'Rourke Helped Retrieve a Vital Ethical Method in Catholic Theology I n one sense, there is nothing new about will suggest several practical implications of this I the theory called "prudential personal- theory for medicine and health care ethics. _^^ism" developed by Fr. Kevin D. WHERE DOES PRUDENTIAL PERSONALISM FIT IN THE O'Rourke, OP, JCD, STM, and his BROADER CONTEXT OF ETHICS?* Dominican confrere, Fr. Benedict M. Ethics is a kind of knowledge, but it differs from BY CHARLES E. Ashley, OP, PhD, through successive edi scientific or technical knowledge because it has to BOUCHARD, OP, do with "oughtness." Ethics, whether based in STD tions of their book Health Care Ethics religious faith or not, always tries to answer two Fr. Bouchard is (HCE)} It is the retrieval of an ethical questions: "What ought I to do?" and "What president and method developed, at least in part, by kind of person ought I to be?" These "doing" associate professor Aristotle, refined and adapted to Christian and "being" questions are at the heart of nearly of moral theology, every ethical system. Aquinas Institute life by St. Thomas Aquinas, and neglected There are two basic ways of answering these of Theology, and distorted by philosophers, reformers, questions, each of which has a variety of subsets St. Louis. and even the church itself. It was reappro- or subcategories. The first basic system is called deontological or "duty-based," because the priated in the 20th century by theologians answer to the "ought" question always refers to and philosophers alike. -

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press. Cover design by David Manahan, o.s.b. Cover symbol by Frank Kacmarcik, obl.s.b. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies / edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-5856-7 (alk. paper) 1. Religion—Dictionaries. 2. Religions—Dictionaries. I. Espín, Orlando O. II. Nickoloff, James B. BL31.I68 2007 200.3—dc22 2007030890 We dedicate this dictionary to Ricardo and Robert, for their constant support over many years. Contents List of Entries ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxxi Entries 1 Contributors 1519 vii List of Entries AARON “AD LIMINA” VISITS ALBIGENSIANS ABBA ADONAI ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM FOXWELL ABBASIDS ADOPTIONISM -

A Proposed Prolegomenon for Normative Theological Ethics with a Special Emphasis on the Usus Didacticus of God's Law John Tape Concordia Seminary, St

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Theology Dissertation Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-1993 A Proposed Prolegomenon for Normative Theological Ethics with a Special Emphasis on the Usus Didacticus of God's Law John Tape Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/thd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tape, John, "A Proposed Prolegomenon for Normative Theological Ethics with a Special Emphasis on the Usus Didacticus of God's Law" (1993). Doctor of Theology Dissertation. 18. http://scholar.csl.edu/thd/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Theology Dissertation by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O it is a living, busy, active, mighty thing this faith. Luther, "Preface to the Epistle of St. Paul to the Romans" CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE: THE DEONTOLOGICAL AND TELEOLOGICAL ELEMENTS IN THEOLOGICAL ETHICS 5 CHAPTER ONE: The Deontological Method Defined and Illustrated 7 Pure Act Deontology 9 Modified Act Deontology 15 Rule Deontology 23 Characteristics of Rule Deontology in the Holy Scriptures 36 Characteristics of Rule Deontology in the Writings of Martin Luther 53 CHAPTER TWO: The Teleological Method -

Cessario Introduction to Moral

Introduction to Moral Theology General Editor: Romanus Cessario, O.P. Introduction to Moral Theology Romanus Cessario, O.P. The Catholic University of America Press Washington, D.C. Copyright © The Catholic University of America Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standards for Information Science—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library materials, .-. ∞ -- Cessario, Romanus. —Introduction to moral theology / Romanus Cessario. ———p.mcm. — (Catholic moral thought) ——Includes bibliographical references and index. —— --- (cloth : alk. paper) — --- (pbk. : alk. paper) ——. Christian ethics.m. Catholic Church—Doctrines.m. Title.m. Series. —.c— —´.—dc For Bernard Francis Cardinal Law Archbishop of Boston on the occasion of his seventieth birthday Contents Acknowledgments, ix Introduction, xi . The Starting Point for Christian Moral Theology Sacra Doctrina and Moral Theology, The Human Person as Imago Dei, Human Flourishing and Beatitudo, . Moral Realism and the Natural Law Divine Providence and the Eternal Law, A Christian View of Natural Law, . The Origin and Structure of Virtuous Behavior The Voluntariness of Christian Freedom, Human Action and the Guidance of Church Teaching, The Primacy of Prudence for a Virtuous Choice, A Brief Speculative Excursion into Freedom and Providence, . The Form of a Good Moral Action Christian Realism and the Form of the Moral Good, Finding Goodness in Objects, Ends, and Circumstances, Virtue, Teleology, and Beatitude, . The Life of Christian Virtue and Freedom Habitus and Virtues: Pattern of a Graced Life, The Gifts of the Holy Spirit: Guides for the Moral Life, The New Law of Freedom: Christ’s Gift to His Church, Appendix Flight from Virtue: The Outlook of the Casuist Systems, Select Bibliography, Index, Acknowledgments “To live is Christ” (Phil :). -

Intuiting Moral Truth Bernard Hoose

Louvain Studies 35 (2011) 53-68 doi: 10.2143/LS.35.1.2084428 © 2011 by Louvain Studies, all rights reserved Intuiting Moral Truth Bernard Hoose Abstract. — In Veritatis splendor, John Paul II made reference to the participation of the practical reason in ethics. Working out the relationship between these two, notes Joseph Selling, is precisely the task of moral theology. This article asks what part, if any, is played in this relationship by intuition. Given the fact that there is a fair amount of confusion, however, it is important to clarify what precisely one means when one refers to intuition. Here the word is used to indicate immediate knowledge, or knowledge that is obtained without any process of reasoning from premises to a conclusion taking place. In the first half of the twentieth century, there was a good deal of debate about the role of intuition in ethics among philosophers who were members of the school of Intuitionism. Early in the second half of that century, however, Intuitionism went out of fashion. Since that time, little attention seems to have been given to the role of intuition in ethics by either philosophers or theologians, in spite of the fact that reasoned arguments about objective ethics always begin with some intuition or other, and some arguments against certain positions amount to nothing more than claims that they lead to conclusions which are counter intuitive. Reasoned argument and intuition, then, should not be seen as opponents. Both, it would seem, have essential roles to play. Access to both, however, can be impeded by ignorance, psychological and cultural conditioning, and structures of sin. -

4 Normative Ethical Theories: Natural Moral

Draft Section B: Ethics and religion Normative ethical 4 theories Introduction This chapter will introduce different approaches to ethical decision-making: ● Deontological ● Teleological ● Character-based Section B of the specifi cation is concerned in its entirety with three normative ethical theories: ● Natural moral law and the principle of double effect, with reference to Aquinas. ● Situation ethics, with reference to Fletcher. ● Virtue ethics, with reference to Aristotle. We shall start, therefore, with a brief overview of some of the terminology. ● Normative ethical theories The word ‘normative’ is an adjective which comes from the word ‘norm’, which means a ‘standard’, or a ‘rule’, so moral norms are standards or principles with which people are expected to comply. Obviously, people have different ideas about what these standards are, so the various normative theories of ethics therefore focus on what they claim makes an action a moral action: on what things are good or bad, and what kind of behaviour is right as opposed to wrong. The three normative theories you are studying therefore illustrate three different sets of ideas about how we should live. Deontology, teleology, consequentialism and character-based ethics are not in themselves ethical theories – they are types of ethical theory. 117 Natural moral law is seen by most people as one type of deontological theory; Kant’s theory of the Categorical Imperative is another. Fletcher’s situation ethics is one type of consequentialist theory; utilitarianism is another. Aristotle’s virtue ethics is a type of teleological theory and is also character- based. The different types of ethical theory are not exclusive, however, so we also find teleological ideas in virtue ethics and situation ethics. -

Perspectives on Peter Singer

GOD, THE GOOD, AND UTILITARIANISM Is ethics about happiness? Aristotle thought so and for centuries Christians agreed, until utilitarianism raised worries about where this would lead. In this volume, Peter Singer, leading utilitarian philosopher and controversial defender of infanticide and euthanasia, addresses this question in conversation with Christian ethicists and secular utilitarians. Their engagement reveals surprising points of agree- ment and difference on questions of moral theory, the history of ethics, and current issues such as climate change, abortion, poverty and animal rights. The volume explores the advantages and pitfalls of basing morality on happiness; if ethics is teleological, is its proper aim the subjective satisfaction of preferences? Or is human flourishing found in objective goods: friendship, intellectual curiosity, meaningful labour? This volume provides a timely review of how utilitarians and Christians conceive of the good, and will be of great interest to those studying religious ethics, philosophy of religion, and applied ethics. john perry is Lecturer in Theological Ethics at the University of St Andrews, and formerly McDonald Fellow for Christian Ethics & Public Life at the University of Oxford. He is the author of The Pretenses of Loyalty (2011). GOD, THE GOOD, AND UTILITARIANISM Perspectives on Peter Singer edited by JOHN PERRY University Printing House, Cambridge cb28bs, United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107050754 © Cambridge University Press, 2014 Chapter 2 ‘Engaging with Christianity’ © Peter Singer, 2014 This publication is in copyright. -

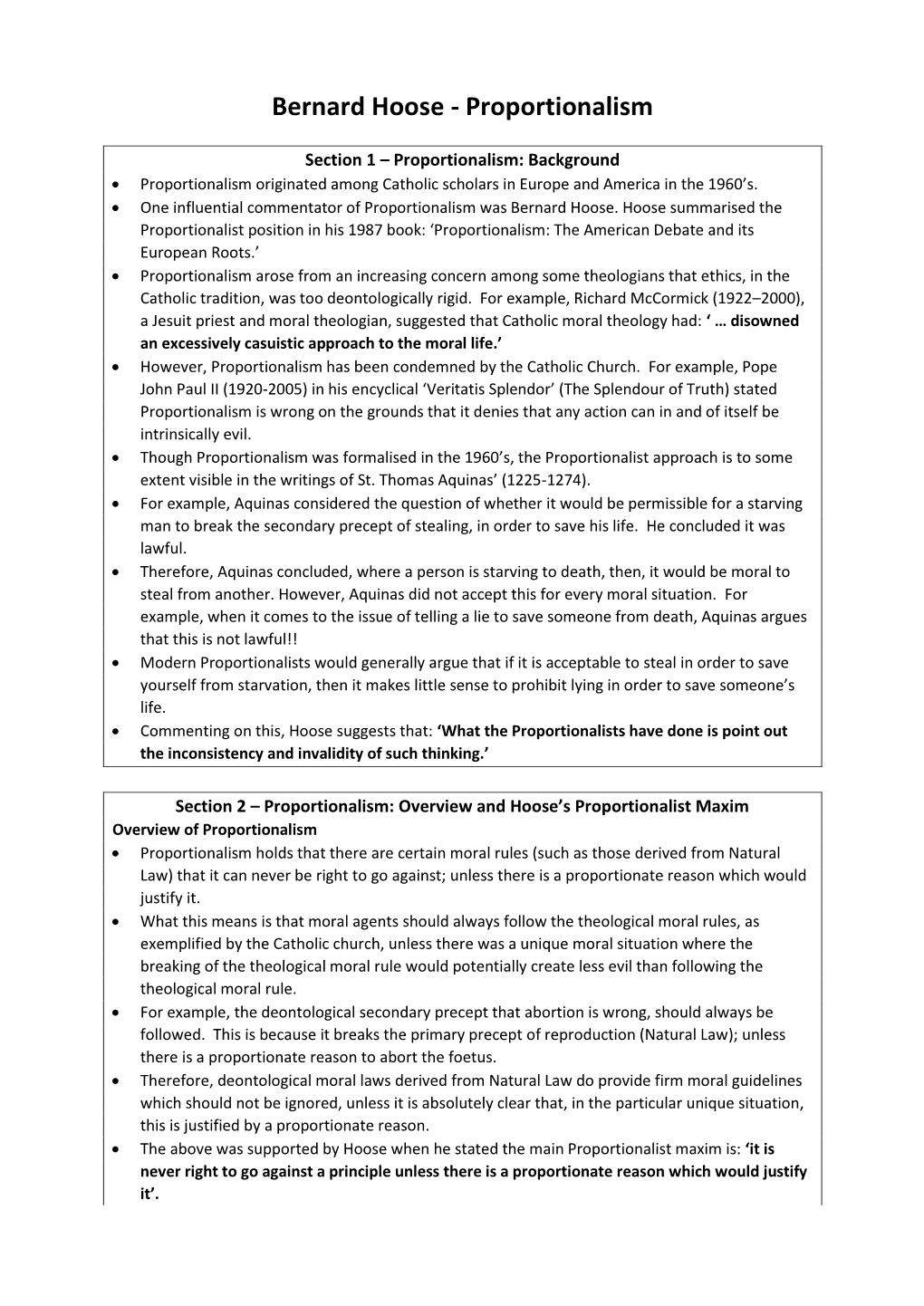

WJEC a Level R.S. Unit 4 Religion and Ethics Knowledge Organiser: Theme 2B Deontological Ethics – Bernard Hoose’S Overview of the Proportionalist Debate

WJEC A Level R.S. Unit 4 Religion and Ethics Knowledge Organiser: Theme 2B Deontological Ethics – Bernard Hoose’s overview of the Proportionalist Debate Key concepts: Key quotes: • The ‘proportionalist debate’ refers to ethical discussions in Roman • Proportionalism concerns Aquinas’ law of double ‘Though preceding from a good intention, an Catholicism about the correct understanding and application of effect (principle of proportionate reason). One act may be rendered unlawful, if it be out of Natural Law. act may have two effects, one unintended. proportion to the end.’ Thomas Aquinas • There is no one, clear Proportionalist ‘theory’ but Proportionalism • Aquinas’ example: Killing in self-defence has ‘We should keep ontic evil to a minimum, but we has been rejected by the Magisterium. (RC Church authority) two effects: 1. saving a life (a primary precept) 2. cannot completely eliminate it in all its forms.’ killing an aggressor (an accidental side effect). • Hoose’s book ‘Proportionalism’ gave a historical overview of the Bernard Hoose developments within proportionalism (revisionism) at the time of • If the level of force is proportionate (not more ‘These theories cannot claim to be grounded in writing. than necessary) killing the aggressor is licit (lawful). the Catholic moral tradition.’ Pope John Paul II • Proportionalists claim that they have the most accurate understanding of Aquinas’ Natural Law. • The good contained in an action must outweigh any evil inadvertently contained in it. (There must • The of Proportionalism is that it is never right to go against ‘maxim’ be more value than disvalue) a principle unless there is a proportionate reason to justify it. -

Is the Teaching of Humanae Vitae Physicalist? a Critique of the View of Joseph A. Selling Mark S

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 62 | Number 4 Article 4 11-1-1995 Is the Teaching of Humanae Vitae Physicalist? A Critique of the View of Joseph A. Selling Mark S. Latkovic Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Latkovic, Mark S. (1995) "Is the Teaching of Humanae Vitae Physicalist? A Critique of the View of Joseph A. Selling," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 62: No. 4, Article 4. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol62/iss4/4 Is the Teaching of Humanae Vitae Physicalist? A Critique of the View of Joseph A. SeUing by Mr. Mark s. Latkovic The following is a condensation of Mr. Latkovic's S. T.L. dissertation. He wishes to express his thanks to the Knights of Columbus, who funded his S. T.L. degree. At present, Mr. Latkovic is Assistant Professor of Moral Theology at Sacred Heart Seminary, Detroit, Ml Since the promUlgation of Pope Paul VI's encyclical Humanae Vitae, (HV)l numerous theologians have dissented from that magisterial teaching for various reasons. Chief among the arguments raised to reject the document's prohibition of contraception has been the charge that the Pope's moral methodology is grounded in a physicalistic understanding ofthe natural law. That is, one that is based on the form of natural law argumentation which proceeds according to the following mistaken pattern: "since nature tends to act in this way, men have a duty to act in this way (that is, according to the way nature acts)."2 When applied to the teaching on sexual morality that is found in the encyclical, this physicalism consists in the contention that, "the moral evaluation of sexual intercourse rests entirely upon the structure and form which the act achieves. -

The Splendor of Truth and Intrinsically Immoral Acts I 29

Studia Philosophiae Christianae UKSW 51(2015)2 JOSEF SEIFERT 7+(63/(1'252)7587+$1',175,16,&$//< ,0025$/$&76,$3+,/2623+,&$/'()(16( 2)7+(5(-(&7,212)3523257,21$/,60$1' &216(48(17,$/,60,1 VERITATIS SPLENDOR* Abstract 7KHSUHVHQWDUWLFOHLVWKH¿UVWSDUWRIDSDSHUWKDWZDVGHOLYHUHGLQDQ abbreviated form, as keynote address, December 16, at the Conference “Ethics of Moral Absolutes Twenty years after V eritatis Splendor , Warsaw 16th–17th December 2013. Containing the word truth in its name, the Encyclical insists that human freedom is based on the foundation of truth. Therefore, even though * 7KHSUHVHQWDUWLFOHLVWKH¿UVWSDUWRIDSDSHUWKDWZDVGHOLYHUHGLQDQDEEUHYLDWHG form, as keynote address, December 16, at the Confererence Ethics of Moral Absolutes Twenty years after ‘Veritatis splendor’ , Warsaw 16th–17th December 2013. As the text was too long for inclusion in the proceedings of the conference, I decided to divide it LQWRWZRDUWLFOHV7KHIROORZLQJLVWKH¿UVWSDUWRIWKHRULJLQDOSDSHU I had published several papers closely related to the content of this essay and given a number of lectures on the topic before, for example a lecture held on 25.01. 1994 at the University of Augsburg, and later published as Der Glanz der sittlichen Wahrheit als Fundament in sich schlechter Handlungen. Die Enzyklika “Veritatis Splendor” von Johannes Paul II , in: Ethik der Tugenden. Menschliche Grundhaltungen als un- verzichtbarer Bestandteil moralischen Handelns. Festschrift für Joachim Piegsa zum 70. Geburtstag , ed. C. Breuer, Eos 2000, 465–487; Ontic and Moral Goods and Evils. 2QWKH8VHDQG$EXVHRI,PSRUWDQW(WKLFDO'LVWLQFWLRQV, Anthropotes 2, Rome 1987; Absolute Moral Obligations towards Finite Goods as Foundation of Intrinsically Right and Wrong Actions. A Critique of Consequentialist Teleological Ethics: Destruction of Ethics through Moral Theology? , Anthropos 1(1985), 57–94; Grundhaltung, Tugend und Handlung als ein Grundproblem der Ethik.