4 Normative Ethical Theories: Natural Moral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Naturalistic Fallacy and Natural Law Methodology

The Naturalistic Fallacy and Natural Law Methodology W. Matthews Grant It is customary to divide contemporary natural law theorists-at least those working broadly within the Thomistic tradition-into two main camps. In one camp are those such as John Finnis, Germain Grisez and Robert George, who deny that a natural law ethics need base itself on premises supplied by a methodologically prior philosophical anthropol ogy. According to these thinkers, practical reason, when reflecting on experience and considering possible ends of action, grasps in a non-in ferential act of understanding certain basic goods that ought to be pursued. Since these goods are not deduced, demonstrated, or derived from prior premises, they provide a set of self-evident or per se nota primary pre cepts from which all other precepts of the natural law may be derived. Because these primary precepts or basic goods are self-evident, natural law theorizing need not wait on the findings of anthropologists and phi losophers of human nature. 1 A rival school of natural law ethicists, comprised of such thinkers as Russell Bittinger, Ralph Mcinerny, Henry Veatch andAnthony Lisska, rejects the claims of Finnis and his colleagues for the autonomy of natural law I. For major statements and defenses of this position see John Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, I980); Germain Grisez, The Way of the Lord Jesus~ vol. I, Christian Moral Principles (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, I983);. Robert P. George, "Recent Criticism of Natural Law -

Part Four - 'Made in America: Christian Fundamentalism' Transcript

Part Four - 'Made in America: Christian Fundamentalism' Transcript Date: Wednesday, 10 November 2010 - 2:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 10 November 2010 Made in America Christian Fundamentalism Dr John A Dick Noam Chomsky: “We must bear in mind that the U.S. is a very fundamentalist society, perhaps more than any other society in the world – even more fundamentalist than Saudi Arabia or the Taliban. That's very surprising.” Overview: (1) Introduction (2) Five-stage evolution of fundamentalism in the United States (3) Features common to all fundamentalisms (4) What one does about fundamentalism INTRODUCTION: In 1980 the greatly respected American historian, George Marsden published Fundamentalism and American Culture, a history of the first decades of American fundamentalism. The book quickly rose to prominence, provoking new studies of American fundamentalism and contributing to a renewal of interest in American religious history. The book’s timing was fortunate, for it was published as a resurgent fundamentalism was becoming active in politics and society. The term “fundamentalism” was first applied in the 1920’s to Protestant movements in the United States that interpreted the Bible in an extreme and literal sense. In the United States, the term “fundamentalism” was first extended to other religious traditions around the time of the Iranian Revolution in 1978-79. In general all fundamentalist movements arise when traditional societies are forced to face a kind of social disintegration of their way of life, a loss of personal and group meaning and the introduction of new customs that lead to a loss of personal and group orientation. -

Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II's Theology of the Body

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-6-2016 Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II’s Theology of the Body: An Analysis of the Historical Development of Doctrine in the Catholic Tradition John Segun Odeyemi Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Odeyemi, J. (2016). Understanding Human Sexuality in John Paul II’s Theology of the Body: An Analysis of the Historical Development of Doctrine in the Catholic Tradition (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1548 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. UNDERSTANDING HUMAN SEXUALITY IN JOHN PAUL II’S THEOLOGY OF THE BODY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CATHOLIC TRADITION. A Dissertation Submitted to Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By John Segun Odeyemi May 2016 Copyright by John Segun Odeyemi 2016 UNDERSTANDING HUMAN SEXUALITY IN JOHN PAUL II’S THEOLOGY OF THE BODY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINE IN THE CATHOLIC TRADITION. By John Segun Odeyemi Approved on March 31, 2016 _______________________________ __________________________ Prof. George S. Worgul Jr. S.T.D., Ph.D. Dr. Elizabeth Cochran Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Rev. Dr. Gregory I. Olikenyen C.S.Sp. Dr. James Swindal Assistant Professor of Theology Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate (Committee Member) School of Liberal Arts iii DEDICATION In honor of my dearly beloved parents on the 50th anniversary of their marriage, (October 30th, 1965 – October 30th 2015) Richard Tunji and Agnes Morolayo Odeyemi. -

Social Norms and Social Influence Mcdonald and Crandall 149

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Social norms and social influence Rachel I McDonald and Christian S Crandall Psychology has a long history of demonstrating the power and and their imitation is not enough to implicate social reach of social norms; they can hardly be overestimated. To norms. Imitation is common enough in many forms of demonstrate their enduring influence on a broad range of social life — what creates the foundation for culture and society phenomena, we describe two fields where research continues is not the imitation, but the expectation of others for when to highlight the power of social norms: prejudice and energy imitation is appropriate, and when it is not. use. The prejudices that people report map almost perfectly onto what is socially appropriate, likewise, people adjust their A social norm is an expectation about appropriate behav- energy use to be more in line with their neighbors. We review ior that occurs in a group context. Sherif and Sherif [8] say new approaches examining the effects of norms stemming that social norms are ‘formed in group situations and from multiple groups, and utilizing normative referents to shift subsequently serve as standards for the individual’s per- behaviors in social networks. Though the focus of less research ception and judgment when he [sic] is not in the group in recent years, our review highlights the fundamental influence situation. The individual’s major social attitudes are of social norms on social behavior. formed in relation to group norms (pp. 202–203).’ Social norms, or group norms, are ‘regularities in attitudes and Address behavior that characterize a social group and differentiate Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, it from other social groups’ [9 ] (p. -

What Normative Terms Mean and Why It Matters for Ethical Eory

What Normative Terms Mean and Why It Matters for Ethical eory* Alex Silk University of Birmingham [email protected] Forthcoming in M. Timmons (Ed.), Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics, Vol. Abstract is paper investigates how inquiry into normative language can improve substantive normative theorizing. First I examine two dimensions along which normative language differs: “strength” and “subjectivity.” Next I show how greater sensitivity to these features of the meaning and use of normative lan- guage can illuminate debates about three issues in ethics: the coherence of moral dilemmas, the possibility of supererogatory acts, and the connection between making a normative judgment and being motivated to act accord- ingly. e paper concludes with several brief reections on the theoretical utility of the distinction — at least so-called — between “normative” and “non- normative” language and judgment. e discussions of these specic linguistic and normative issues can be seen as case studies illustrating the fruitfulness of utilizing resources from philosophy of language for normative theory. Get- ting clearer on the language we use in normative conversation and theorizing can help us diagnose problems with bad arguments and formulate better mo- tivated questions. is can lead to clearer answers and bring into relief new theoretical possibilities and avenues to explore. *anks to Eric Swanson and the audience at the Fih Annual Arizona Normative Ethics Work- shop for discussion, and to two anonymous referees for comments. Contents Introduction Weak and strong necessity Endorsing and non-endorsing uses Dilemmas Supererogation Judgment internalism and “the normative” Conclusion Introduction e strategy of clarifying philosophical questions by investigating the language we use to express them is familiar. -

War Rights and Military Virtues: a Philosophical Re-Appraisal of Just War Theory

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2014 War rights and military virtues: A philosophical re-appraisal of Just War Theory Matthew T. Beard University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Beard, M. T. (2014). War rights and military virtues: A philosophical re-appraisal of Just War Theory (Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/96 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. War Rights and Military Virtues A Philosophical Re-appraisal of Just War Theory Doctoral Thesis Prepared by Matthew T. Beard School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia Supervised by Christian Enemark and Hayden Ramsay Supported by The Morris Research Scholarship Declaration I, Matthew Thomas Beard, declare that this PhD thesis, entitled War Rights and Military Virtues: A Philosophical Re-appraisal of Just War Theory is no more than 100,000 words exclusive of title pages, table of contents, acknowledgements, list of figures, reference list, and footnotes. The thesis is my own original work, prepared for the specific and unique purposes of this academic degree and has not been submitted in whole or part for the awarding of any other academic degree at any institution. -

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

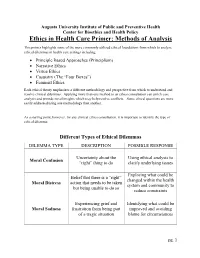

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

Thomist Natural Law

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 8 Number 1 Volume 8, Winter 1962, Number 1 Article 5 Thomist Natural Law Joaquin F. Garcia, C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THOMIST NATURAL LAW JOAQUIN F. GARCIA, C.M.* N THE Summer 1960 edition of The Catholic Lawyer, Dr. R. D. Lumb, a Lecturer in Law at the University of Queensland, had an article entitled "Natural Law - An Unchanging Standard?", in which he con- sidered the doctrines of two thinkers, St. Thomas and Suarez. It is the opinion of this writer that as far as Thomist Natural Law is concerned, Dr. Lumb could have omitted the question mark. It is an unchanging standard. Dr. Lumb set himself the task of ascertaining whether the traditional Thomist system takes into account the variables to be found in any system of rules or institutions. The Thomist system of law does take account of the variables but through positive law, through the application of the universal Natural Law principles to particular changing conditions. By no means does it replace positive law. Unlike 18th century rationalis- tic Natural Law which often ignored experience, which often contained personal, social and political programs, and which often was not Natural Law at all but positive law under a Natural Law label, Thomist Natural Law offers the widest scope for positive law and stresses the importance of experience. -

Philosophy of Natural Law

4YFPMWLIHMR-RWXMXYXI W.SYVREP7IT PHILOSOPHY OF NATURAL LAW Justice K. N. Saikia Former Judge Supreme Court of India. Director General National Judicial Academy By philosophy of law, for the purpose of this article, is meant the pursuit of wisdom, truth and knowledge of law by use of reason. In other words, philosophy of law means the ratlonal investigation and study of the basic ideal and principles of law. The philosophy of natural law is the subject of this article. Longing for a Higher Law - In the human bosom there has always been a longing for a higher law than those made by the community itself. The divine theory of law, the theory of natural law, and the principles of natural justice are some theories or notions found in fulfilment of this longing. Divine laws are those ascribed to God. Divine rights of kings were supposed to have been derived from God. Laws which are claimed to be God-made, may not be amendable by man; and their reasoning and provisions also not to be ques- tioned by man. Greek thinkers from Homer to the Stoics, and reflections of Plato and Aristotle mainly provide the beginning of systematic legal thinking. In Homer, law is embodied in the themistes which the kings receive from Zeus as the divine source of all earthly justice which is still identical with order and authority. Solon the great Athenian lawgiver appeals to Dike, the daughter of Zeus, as a guarantor of justice against earthly tyranny, violation of rights and social injustice. The Code of Hamurapi was handed over by the Sun god. -

Duty-To-Protect.Pdf

2 APA PRACTICE ORGANIZATION LEGAL ISSUES Duty to Protect A BRIEF HISTORY OF DUTY TO PROTECT In 1976, the California Supreme Court issued its decision in Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of Roles and Responsibilities for California after a patient carried out a threat to kill a Psychologists young woman. In that case, the court ruled: When a therapist determines, or pursuant to the ecent mass shootings heightened the focus on standards of his profession should determine, that widespread state laws that require or allow his patient presents a serious danger of violence psychologists and other mental health professionals R to another [person], he incurs an obligation to use to breach confidentiality in order to prevent harm by their reasonable care to protect the intended victim potentially violent patients. This article is intended to help against such danger . [This duty] may call for practitioners with the challenging task of applying these [the therapist] to warn the intended victim or duty to protect* laws in working with these individuals. others likely to apprise the victim of the danger, to notify the police, or take whatever other steps are Mandatory versus permissive laws reasonably necessary under the circumstances. Most psychologists think of duty to protect laws as those After the Tarasoff case, many states passed legislation that create a mandatory obligation to take action and impose defining a “duty to protect”* and the steps needed to liability for failing to carry out that duty. But there are closely discharge that duty. In other states, courts created a related laws that give psychologists discretion or permission duty to protect through case law. -

Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Addressing Fundamentalism by Legal and Spiritual Means By Dan Wessner Religion and Humane Global Governance by Richard A. Falk. New York: Palgrave, 2001. 191 pp. Gender and Human Rights in Islam and International Law: Equal before Allah, Unequal before Man? by Shaheen Sardar Ali. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 2000. 358 pp. Religious Fundamentalisms and the Human Rights of Women edited by Courtney W. Howland. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. 326 pp. The Islamic Quest for Democracy, Pluralism, and Human Rights by Ahmad S. Moussalli. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. 226 pp. The post-Cold War era stands at a crossroads. Some sort of new world order or disorder is under construction. Our choice to move more toward multilateralism or unilateralism is informed well by inter-religious debate and international law. Both disciplines rightly challenge the “post- Enlightenment divide between religion and politics,” and reinvigorate a spiritual-legal dialogue once thought to be “irrelevant or substandard” (Falk: 1-8, 101). These disciplines can dissemble illusory walls between spiritual/sacred and material/modernist concerns, between realpolitik interests and ethical judgment (Kung 1998: 66). They place praxis and war-peace issues firmly in the context of a suffering humanity and world. Both warn as to how fundamentalism may subjugate peace and security to a demagogic, uncompromising quest. These disciplines also nurture a community of speech that continues to find its voice even as others resort to war. The four books considered in this essay respond to the rush and risk of unnecessary conflict wrought by fundamentalists.