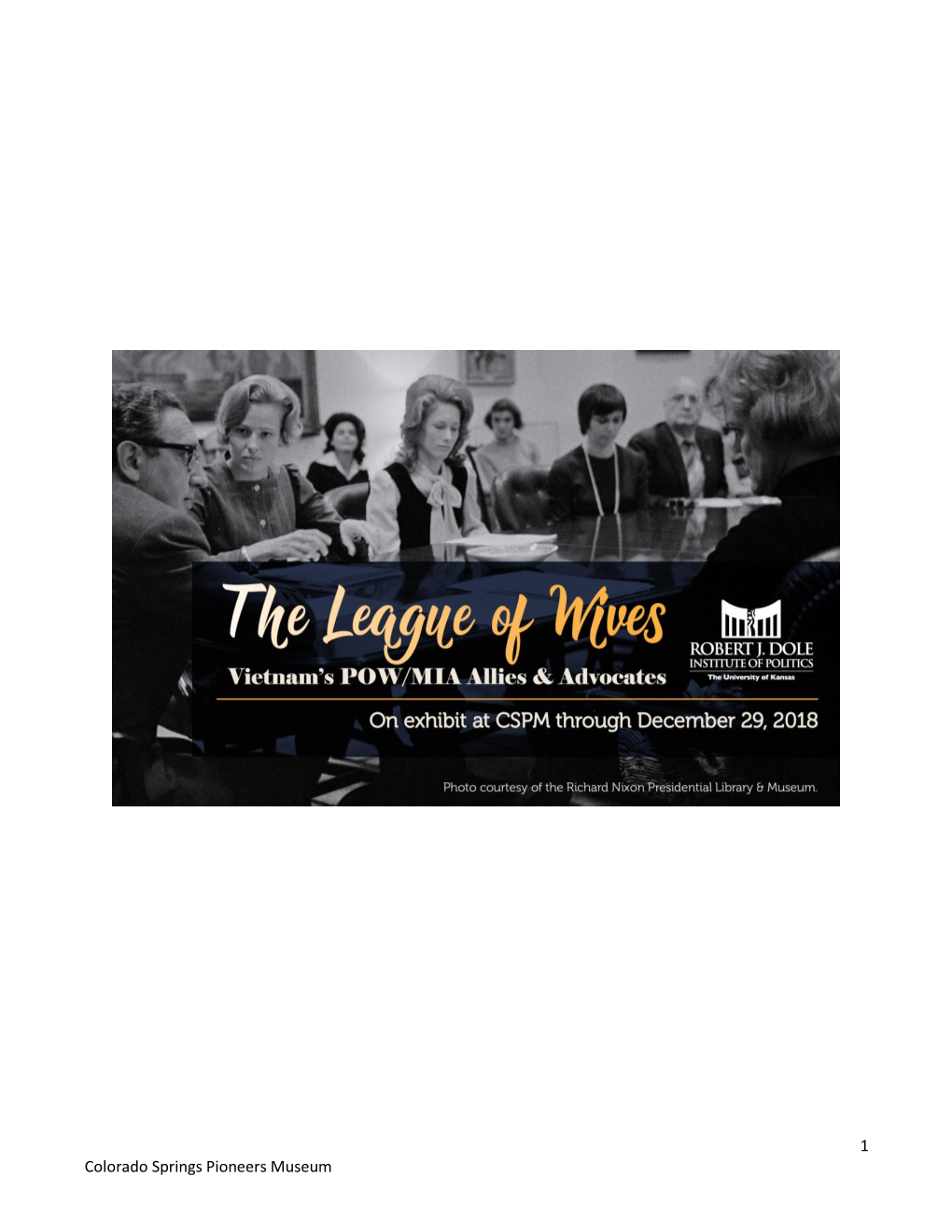

1 Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum CSPM Exhibit Text, Leah Davis Witherow, Curator of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maternal Activism

1 Biography as Philosophy The Power of Personal Example for Transformative Theory As I have written this book, my kids have always been present in some way. Sometimes, they are literally present because they are beside me playing, asking questions, wanting my attention. Other times, they are present in the background of my consciousness because I’m thinking about the world they live in and the kind of world I want them to live in. Our life together is probably familiar to many U.S. middle-class women: I work full-time, the kids go to school full time, and our evenings and weekends are filled with a range of activities with which we are each involved. We stay busy with our individual activities, but we also come together for dinner most nights, we go on family outings, and we enjoy our time together. As much time as I do spend with my kids, I constantly feel guilty for not doing enough with them since I also spend significant time preparing for classes, grading, researching, and writing while I’m with them. Along with many other women, I feel the pressure of trying and failing to balance mothering and a career. Although I feel as though I could be a better mother and a bet- ter academic, I also have to concede that I lead a privileged life as a woman and mother. Mothers around the world would love to have the luxury of providing for their children’s physical and mental well-being. In the Ivory Coast and Ghana, children are used as slave labor to harvest cocoa beans for chocolate (Bitter Truth; “FLA Highlights”; Hawksley; The Food Empowerment Project). -

FOR a FUTURE of Peketjiktice

WDMENS ENCAMPMENT FOR A FUTURE OF PEKEtJIKTICE SUMMER 1983'SENECA ARM/ DEPOTS 1590 WOMEN OF THE H0TINONSIONNE IROaiMS CONFEDERACY GATHER AT SENECA TO DEMAND AN END TO MMR AMONG THE NATIONS X 1800s A&0LITI0NIST5 M4KE SENECA COUNTY A MAJOR STOP ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD HITO HARRIET TUBMAW HOUSE NEAR THE PRESENT DAI ARMV DEPOTS EARL/ FEMINISTS HOLD FIRST WDMENS RIQHTS CONVENTION AT SENEGA FALLS ID CALL FOR SUFFRAGE & EQUAL MPTICJMTION IN ALL OTHEP AREAS OF LIFE ' TOD/W URBAN & RURA. WOMEN JOIN TOGETHER IN SENECA G0UNI7 TO CHALLENGE "ME NUCLEAR THREAT TO UFE ITSELF^ WE FOCUS ON THE WEAPONS AT 1UE SENECA ARMY DEPOT TO PREVENT DEPU)yMENT OF NATO MISSILES IN SOUDARITY WITH THE EUPOPE/W PEACE MO^MENT^ RESOURCE HANDBOOK Introduction The idea of a Women's Peace Camp in this country in solidarity with the Peace Camp movement in Europe and the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, in particular, was born at a Conference on Global Feminism and Disarmament on June 11, 1982. The organizing process began with discussions between Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and women in the Upstate Feminist Peace Alliance (NY), to consider siting the camp at the Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, NY. The planning meetings for the Encampment have since grown to include women from Toronto, Ottawa, Rochester, Oswego, Syracuse, Geneva, Ithaca, Albany, New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, and some of the smaller towns in between. Some of the tasks have been organized regionally and others have been done locally. Our planning meetings are open, and we are committed to consensus as our decision making process. -

The War Divides America

hsus_te_ch16_s03_s.fm Page 656 Friday, January 16, 2009 8:33 PM ᮤ A Vietnam veteran protests the war in 1970. WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO Step-by-Step The “Living-Room War” SECTION Instruction Walter Cronkite, the anchor of the CBS Evening News, 3 was the most respected television journalist of the 1960s. His many reports on the Vietnam War were SECTION 3 models of balanced journalism and inspired the Objectives confidence of viewers across the United States. But during the Tet Offensive, Cronkite was shocked by the As you teach this section, keep students disconnect between Johnson’s optimistic statements focused on the following objectives to help and the gritty reality of the fighting. After visiting them answer the Section Focus Question and Vietnam in February of 1968, he told his viewers: master core content. “We have been too often disappointed by the • Describe the divisions within American optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam society over the Vietnam War. and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silverlinings they find in the darkest clouds.... [I]t • Analyze the Tet Offensive and the seems now more certain than ever that the bloody American reaction to it. experience of Vietnam is to end in stalemate.” • Summarize the factors that influenced the —Walter Cronkite, 1968 outcome of the 1968 presidential election. ᮡ Walter Cronkite The War Divides America Prepare to Read Objectives Why It Matters President Johnson sent more American troops • Describe the divisions within American society to Vietnam in order to win the war. But with each passing year, over the Vietnam War. -

Mf-$0.65 Bc$3.29

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 063 194 SO 002 791 AUTHOR Abrams, Grace C.; Schmidt, Fran TITLE Social Studies: Peace In the TwentiethCentury. INSTITUTION DadeCounty Public Schools, Miami,Fla. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 62p. BDPS PRICE MF-$0.65 BC$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Activity Units; Behavioral Objectives;*Conflict Resolution; Curriculum Guides; *ForeignRelations; Grade 7; Grade 8; Grade 9; HumanRelations; *International Education; Junior HighSchools; Modern History; Nationalism; Organizations(Groups); *Peace; Resource Guides; *Social StudiesUnits; Violence; War; World Affairs; World Problems IDENTIFIERS Florida; *Quinmester Programs ABSTRACT This study of the effort and failuresto maintain world peace in this century is intended as anelective, quinmester course for grades 7 through9. It encompasses the concept of nationalism and the role it plays inthe decisions that lead to war, and organizations that havetried and are trying topreserveor bring about peace. Among other goals for the course areforthestudent to: 1) assess his own attitudes andbeliefs concerning peace and generalize about the nature of war; 2)examine the social, political, and economic reasons for war; 3)analyze breakdowns in world peacein this century and the resultant humanproblems; 4) investigate and suggest alternatives toWar as a means of settling conflict; and, 5) describe ways and means an individual canwork for peace. The guide itself is divided into a broad goalssection, a content outline, objectives and learning activities,and teacher/student materials. Learning activities are highlyvaried and are closely tied with course objectives.Materials include basic texts,pamphlets,records, and filmstrips. Relateddocuments are: SO 002 708 through SO 002718, SO 002 76.8 through SO002 792, and SO 002 947 through SO002 970. -

88 the Uprising of POW/MIA Wives

Journal of Leadership Education DOI: 10.12806/V13/I4/C10 Special 2014 The Uprising of POW/MIA Wives: How Determined Women Forced America, Hanoi, and the World to Change Steven L. Smith Wayland Baptist University Abstract In the fall of 1966, a small and informal group of wives whose husbands were classified as Prisoner of War (POW) or Missing in Action (MIA) formed a small and informal group. By December 12, 1969, this group of women had gained such power, influence, and a multitude of disparate followers that twenty-six met with President and Mrs. Pat Nixon at the White House. In part, the POW/MIA story is about a small group of women taking a decisive role to change the United States POW/MIA policy, accentuate the plight of the prisoners, and demand humane treatment by Hanoi—all in a national and global arena. Introduction The war in Vietnam was tremendously divisive not only among American citizens, but also among other democratic and communists nations. Demonstrations against the war, both peaceful and violent, were part of the American fabric in the late 1960s. Military personnel were subject to public scorn and viewed by the citizenry with contempt for their service in Vietnam. To use the trite phrase that the war in Vietnam was not a "popular war" fails to convey the seething national hostility and unrest of the era. However, by the late 1960s, the POW/MIA issue had become a national unifying cause that culminated in Operation Homecoming in February- March of 1973. At the time, the United States Department of State was responsible for handling all POW/MIA matters, not the Department of Defense (Davis, 2000; Rochester & Kiley, 1998). -

The History and Memory of 'Women Strike for Peace', 1961-1990

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Coburn, Jon (2015) Making a Difference: The History and Memory of ‘Women Strike for Peace’, 1961-1990. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/30339/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Making a Difference: The History and Memory of ‘Women Strike for Peace’, 1961-1990 Jon Coburn PhD 2015 Making a Difference: The History and Memory of ‘Women Strike for Peace’, 1961-1990 Jon Coburn A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences December 2015 Abstract The women’s antinuclear protest group Women Strike for Peace (WSP) formed a visible part of the US peace movement during the Cold War, recording several successes and receiving a positive historical assessment for its maternal, respectable image. -

Motherhood and Protest in the United States Since the Sixties

Motherhood and Protest in the United States Since the Sixties Georgina Denton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History November 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Georgina Denton ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to take this opportunity to thank my supervisors Kate Dossett and Simon Hall, who have read copious amounts of my work (including, at times, chapter plans as long as the chapters themselves!) and have always been on hand to offer advice. Their guidance, patience, constructive criticism and good humour have been invaluable throughout this whole process, and I could not have asked for better supervisors. For their vital financial contributions to this project, I would like to acknowledge and thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Association for American Studies and the School of History at the University of Leeds. I am grateful to all the staff and faculty in the School of History who have assisted me over the course of my studies. Thanks must also go to my fellow postgraduate students, who have helped make my time at Leeds infinitely more enjoyable – including Say Burgin, Tom Davies, Ollie Godsmark, Nick Grant, Vincent Hiribarren, Henry Irving, Rachael Johnson, Jack Noe, Simone Pelizza, Juliette Reboul, Louise Seaward, Danielle Sprecher, Mark Walmsley, Ceara Weston, and Pete Whitewood. -

Shalom May 2019

May, 2019 Vol. 48 No. 4 Jewish Peace Letter Published by the Jewish Peace Fellowship CONTENTS Happy Mother’s pDay! h We will return with our usual larger issue next month. It’s Mothers Day Again and We’re Still at War Murray Polner, Pg. 2 2 • May, 2019 jewishpeacefellowship.org Forever Wars It’s Mother’s Day Again and We’re Still at War Murray Polner fter the carnage of the Second World War, the members of the now defunct Victory Chapter of the American Gold Star Mothers in St. Petersburg, Florida, knew better than most what it was to lose their sons, daughters, husbands, and other near relatives in war. “We’d rather not talk about it,” one mother, whose son was killed in WWII, told the St. Petersburg Times fifteen years after the war ended. “It’s a terrible scar that never heals. We hope Athere will never be another war so no other mothers will have to go through this ordeal.” But thanks to our wars in Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Panama, the Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan—not to mention our proxy wars around Mother’s Day the globe—too many moms (and dads too) now have to mourn “should be family members badly scarred or devoted to the lost to wars dreamed up by the demagogic, ideological, and myopic. advocacy of But every year brings our wonderful Mother’s Day. Few peace doctrines.” Americans know that Mother’s —Julia Ward Howe Day was initially suggested by two peace-minded mothers, Julia Ward Howe, a nineteenth century anti- slavery activist and suffragette who wrote the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and Anna Reeves Jarvis, mother of eleven, who influenced Howe and once asked her fellow Appalachian townspeople, badly polarized by the carnage of the American Civil War, to remain neutral and help Julia Ward Howe, who wrote “Battle nurse the wounded on both sides. -

Thematic Essay Question

REGENTS EXAM IN U.S. HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT The University of the State of New York REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION UNITED STATES HISTORY AND GOVERNMENT Wednesday, June 15, 2016 — 1:15 to 4:15 p.m., only Student Name ______________________________________________________________ School Name _______________________________________________________________ The possession or use of any communications device is strictly prohibited when taking this examination. If you have or use any communications device, no matter how briefly, your examination will be invalidated and no score will be calculated for you. Print your name and the name of your school on the lines above. A separate answer sheet for Part I has been provided to you. Follow the instructions from the proctor for completing the student information on your answer sheet. Then fill in the heading of each page of your essay booklet. This examination has three parts. You are to answer all questions in all parts. Use black or dark-blue ink to write your answers to Parts II, III A, and III B. Part I contains 50 multiple-choice questions. Record your answers to these questions as directed on the answer sheet. Part II contains one thematic essay question. Write your answer to this question in the essay booklet, beginning on page 1. Part III is based on several documents: Part III A contains the documents. When you reach this part of the test, enter your name and the name of your school on the first page of this section. Each document is followed by one or more questions. Write your answer to each question in this examination booklet on the lines following that question. -

2009 President's Report

SOCIETY OF SPONSORS OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY PRESIDENT’S REPORT MAY 2008—MAY 2009 (I have represented the Society at 8 christenings and 7 commissionings since the May 2008 Annual Meeting; additionally, sponsors have participated in 3 keel authentications. Don’t forget to visualize these special events---and maybe attend one next year!) Following our Centennial Year Annual Meeting on May 8, I departed for Bath Maine. There on May 10, 2008, a blustery but sunny day at Bath Iron Works (BIW), STOCKDALE (DDG-106), named for a great American hero and Naval Officer, Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale, was christened by his widow, Mrs. Sybil Stockdale, assisted by her Maid of Honor and eldest grand daughter, Elizabeth Stockdale. VADM Stockdale was a Medal of Honor recipient as well as a Vice Presidential candidate with Ross Perot. He spent 7 1/2 years as a Prisoner of War. Sybil Bailey Stockdale is a founder of the NATIONAL LEAGUE OF FAMILIES OF AMERICAN PRISONERS AND MISSING IN SE ASIA. She met with Henry Kissinger, President Nixon and even the Viet Nam delegation at the Paris Peace Talks. She was the first wife of an active duty officer to receive the Navy’s Distinguished Public Service Award. With her husband she co-authored the book IN LOVE AND WAR. She is also the sponsor of AVENGER (MCM-1) and a life member of the Society. The four Stockdale sons and several grandchildren shared in the festivities along with some of his fellow POWs. As has often been the case this year, the bottle did not break the first time but BIW was prepared to try again and the second time was a success. -

Live Auction Catalog

LIVE AUCTION CATALOG PRESIDENT AND MRS. CARTER’S 2018 CARTER CENTER WEEKEND Values expressed in this catalog represent certified appraisals, esti- mates based on sales of comparable items at previous auctions, or sales of similar items from internet sites such as eBay. Any amount paid above the stated value will be considered a donation to The Carter Center and will be tax-deductible. Please read carefully the conditions for travel packages and other restrictions. You can also see these items online at our website: www.cartercenter.org. If a remote bidder desires proxy representation by Carter Center staff for the live auction, those arrangements need to be made with Dianne Bryant by 5 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time (PDT) on June 30, 2018. To make arrangements for bidding by proxy and for details on submitting bids by fax, please see the auction bid sheet at the end of this catalog. Bids submitted via fax will be taken until 4 p.m. PDT on June 30, 2018. Photographs of most auction items were taken by Katie Archibald- Woodward. Additional photographs were received from donors of items and corporate and internet sources. Shipping costs will be added to items that need to be shipped. 2 1 CAMP DAVID MEMORABILIA In addition to serving as a retreat for the President of the United States, Camp David was also the site of the famous meetings in September 1978 that resulted in the signing of the Camp David Accords. Offered here are a 21-inch by 15-inch photo- graph of Jimmy Carter, Menachem Begin, and Anwar Sadat, signed by President Carter; a collection of six glasses emblazoned with the Camp David insignia; and a set of Camp David playing cards from the President Kennedy era. -

WIN Magazine V13 N25 1977

.î I WestÞrn Jews descend from the Khazar he Dhurna. " But Shridharani notes that what would he say now? Certainly - . Empire of the eighth through twelth cen- sittins in front oftroop trains and dock- would consider Sèabrook far closer to his I it turies. But dofind an interesting workðrs unloading ammunition was ideal than a protest involving secrecy thesis. It helps to explain why I looË as I used anvwav, and "thatthe movement and property damage. To me it seems why are so do, there many "Russian" in this réspect has gone beyond the men thatìf oõcup:iers weie willing to be re- Jews, and a number ofothet historical who orieinated it. " moved witli no tesistance to arrest' they events and phenomenon. Mass conver- candli himself relaxed his strict were reducing the imposition of their sions, such as that of Khazarcin740, on otheri to a minimum. I do feel limits asainst bovcotting. Gene Sharp- wills were nÒt unusual. They were frequently savs Gaîdhi in 1930-31 favored boy- manv of us need to be more sensitive to political moves of the highest order, as in coitine onlv cloth, considedng a more beinä sometimes PhYsicallY (L'Ifl, Russia when the Tsat decided that he extenlive lioycott as "coereivè." After overEearins. I recãll a recent demo and his subjects would be ofthe Eastern 1932he "fav-ored an economicboycott of aeainstthe-B-l in Los Angeleswhere ' Orthodox persuasion. Later, in lYestern an aggressor nation" as suggested by aãioinine businesses had to call the cops Europe, princes and rulers decided the Iirãian National Congress, which beäause-we were inadvertantly blocking 1uly14,1977 I Vol.