Ma Jian and Gao Xingjian: Intellectual Nomadism and Exilic Consciousness in Sinophone Literature Shuyu Kong Simon Fraser University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

What I Wish My College Students Already Knew About PRC History

Social Education 74(1), pp 12–16 ©2010 National Council for the Social Studies What I Wish My College Students Already Knew about PRC History Kristin Stapleton ifferent generations of Americans understand China quite differently. This, Communist Party before 1949 because of course, is true of many topics. However, the turbulence of Chinese they believed its message of discipline Dhistory and U.S.-China relations in the 60 years since the founding of the and “power to the people” could unify People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 has deepened the gaps in generational the country, defeat the Japanese invad- thinking about China.1 If you came of age in the America of the 1950s and 1960s, ers, and sweep out the weak, corrupt you remember when China seemed like North Korea does today—isolated, aggres- Nationalist government. sive, the land of “brain washing.” If you first learned about China in the 1970s, Like Wild Swans, other memoirs then perhaps, like me, you had teachers who were inspired by Maoist rhetoric and of the Red Guard generation explore believed young people could break out of the old culture of self-interest and lead why children born after the Communist the world to a more compassionate future. The disillusion that came with more “Liberation” of China in 1949 put such accurate understanding of the tragedies of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural faith in Mao and his ideas.2 Certainly Revolution led some of us to try to understand China more fully. Many of my the cult of personality played a major college-age students, though, seem to have dismissed most PRC history as just role. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

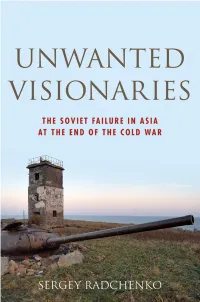

Unwanted Visionaries

oxfordhb-9780199938773.indd vi 12/4/2013 8:07:55 PM Unwanted Visionaries oxfordhb-9780199938773.indd i 12/4/2013 8:07:53 PM Oxford Studies in International History JAMES J. SHEEHAN, SERIES ADVISOR Th e Wilsonian Moment : Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism Erez Manela In War ’ s Wake : Europe ’ s Displaced Persons in the Postwar Order Gerard Daniel Cohen Grounds of Judgment : Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan Pär Kristoff er Cassel Th e Acadian Diaspora : An Eighteenth-Century History Christopher Hodson Gordian Knot : Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order Ryan Irwin Th e Global Off ensive: Th e United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post–Cold War Order Paul Th omas Chamberlin Unwanted Visionaries : Th e Soviet Failure in Asia at the End of the Cold War Sergey Radchenko L a m a z e : An International History Paula A. Michaels oxfordhb-9780199938773.indd ii 12/4/2013 8:07:55 PM Unwanted Visionaries The Soviet Failure in Asia at the End of the Cold War Sergey Radchenko 1 oxfordhb-9780199938773.indd iii 12/4/2013 8:07:55 PM 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. -

Niamh Hartley

Niamh Hartley Jung Chang is a bestselling author originally from Chengdu, China and was an English-language student at Sichuan university (1). Her book, Wild Swans – Three Daughters of China, tells the tale of three generations of Chinese women during the rise and fall of Mao. According to Asian Wall Street Journal, it is the most read book about China and Chinese history. Jung Chang came to the University of York in 1978 and obtained a PhD in Linguistics in 1982 (2). She was the first person from the People’s Republic of China to receive a doctorate from a British University (3). Growing up during the Cultural Revolution meant Chang worked as a peasant, a “barefoot” doctor, a steelworker and an electrician (4). After travelling to the UK and experiencing how different the two cultures were, Jung Chang was inspired to tell her and her family’s stories. In relation to her time spend studying abroad, Chang expressed her surprise; “to keep an open mind was a bombshell” (5). Although this could relate to the environment in communist China, it also shows how her time in a different country was able to give her a new perspective on the world. By reflecting on her past and wanting to educate people on the history of China she wrote her family history in Wild Swans. By coming to England for her PhD, she could educate people on her country, opening the communication across cultures and countries. Furthermore, her book has been translated into more than 30 languages (6). This is an extreme example of how studying abroad can help connect cultures and allow different nationalities to empathise with each other. -

Tragic Anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests and Massacre

TRAGIC ANNIVERSARY OF THE 1989 TIANANMEN SQUARE PROTESTS AND MASSACRE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2013 Serial No. 113–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–341PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:13 Nov 03, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\060313\81341 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

WILD SWANS Jung Chang

Cadernos de Literatura em Tradução no. 4, p. 195-212 WILD SWANS Jung Chang Sandra Negretti Wild Swans – Three Daughters of China is written by a contemporary Chinese woman, Jung Chang (1952), who narrates the story of a century of her ancestors (focusing mainly on the women) and their lives from feudal China through the Cultural Revolution to Post- Revolutionary China. Jung Chang’s book has been translated into 25 languages and has sold over 7 million copies world-wide, reaching number 1 in over a dozen countries, including Brazil. Wild Swans was originally published in hardcover by Simon & Schuster in 1991. The Anchor Books edition, was firstly published in November 1992. The Portuguese version was translated by Marcos Santarrita and was published by Companhia das Letras in 1994 for the first time. The book was originally written in English. At the beginning of my translation I decided to try to translate as closely as possible to the Portuguese version, that is, using words similar to Portuguese words, dealing with the problematic words at the end of the job, keeping the same punctuation even though there are different rules for these two languages, and using British English. 195 NEGRETTI, Sandra. Wild Swans The original book has 524 pages and the Portuguese version 485. Both books have 28 chapters and the Epilogue, the Acknowlegments, the Author’s Note, the Family Tree, the Chronology, a Map and in the original version there is an Index. I worked with Chapter 3 “Todos dizem que Manchukuo é uma terra feliz”- a vida sob os Japoneses (1938-1945), in the original version “They All Say What a Happy Place Manchukuo is”- Life under the Japanese (1938-1945). -

Disambiguation, a Tragedy

NAN Z. DA Disambiguation, a Tragedy Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, the contemporary Chinese American writer Yiyun Li recounts something that Marianne Moore’s mother had done, which recalled something that Li’s own mother had done. The young Marianne Moore had become attached to a kitten that she named Buffy, short for Buffalo. One day, her mother drowned the creature, an act of cruelty that Moore inexplicably defends: “We tend to run wild in these matters of personal affection but there may have been some good in it too.” Li appends a version of this story from her own childhood: Having something that you love snatched away because you love it is maddening because there’s no way to gainsay it. You can only protest on the grounds that indeed you experience the attachment of which you’re accused. This leaves the child Li in a position roughly analogous to anyone who, having been punctured, bristles at the accusation of being thin- skinned. Protesting would have been to play into her mother’s hands, proving her mother right. Everyone knows the stereotype of the Asian tiger mother, the cold, over-scrutinizing mother popularized by Amy Chua’s 2011 self-described memoir and parenting manual. Asian tiger mothers conjure other Asian parenting stereotypes (and, if we’re being honest with ourselves, Asian realities): parents who are averse to pet ownership, who hold a fluid interpretation of personal property (especially when gifts are involved), who simply inform you that “what is best for you” has been done. -

China As Dystopia: Cultural Imaginings Through Translation Published In: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) Doi: 10.1080/1

China as dystopia: Cultural imaginings through translation Published in: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) doi: 10.1080/14781700.2015.1009937 Tong King Lee* School of Chinese, The University of Hong Kong *Email: [email protected] This article explores how China is represented in English translations of contemporary Chinese literature. It seeks to uncover the discourses at work in framing this literature for reception by an Anglophone readership, and to suggest how these discourses dovetail with meta-narratives on China circulating in the West. In addition to asking “what gets translated”, the article is interested in how Chinese authors and their works are positioned, marketed, and commodified in the West through the discursive material that surrounds a translated book. Drawing on English translations of works by Yan Lianke, Ma Jian, Chan Koonchung, Yu Hua, Su Tong, and Mo Yan, the article argues that literary translation is part of a wider programme of Anglophone textual practices that renders China an overdetermined sign pointing to a repressive, dystopic Other. The knowledge structures governing these textual practices circumscribe the ways in which China is imagined and articulated, thereby producing a discursive China. Keywords: translated Chinese literature; censorship; paratext; cultural politics; Yan Lianke Translated Literature, Global Circulations 1 In 2007, Yan Lianke (b.1958), a novelist who had garnered much critical attention in his native China but was relatively unknown in the Anglophone world, made his English debut with the novel Serve the People!, a translation by Julia Lovell of his Wei renmin fuwu (2005). The front cover of the book, published by London’s Constable,1 pictures two Chinese cadets in a kissing posture, against a white background with radiating red stripes. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

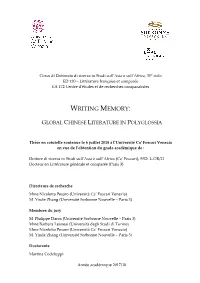

Writing Memory

Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA Thèse en cotutelle soutenue le 6 juillet 2018 à l’Université Ca’ Foscari Venezia en vue de l’obtention du grade académique de : Dottore di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa (Ca’ Foscari), SSD: L-OR/21 Docteur en Littérature générale et comparée (Paris 3) Directeurs de recherche Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Membres du jury M. Philippe Daros (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Mme Barbara Leonesi (Università degli Studi di Torino) Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Doctorante Martina Codeluppi Année académique 2017/18 Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes Tesi in cotutela con l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3: WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA SSD: L-OR/21 – Littérature générale et comparée Coordinatore del Dottorato Prof. Patrick Heinrich (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Supervisori Prof.ssa Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Prof. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Dottoranda Martina Codeluppi Matricola 840376 3 Écrire la mémoire : littérature chinoise globale en polyglossie Résumé : Cette thèse vise à examiner la représentation des mémoires fictionnelles dans le cadre global de la littérature chinoise contemporaine, en montrant l’influence du déplacement et du translinguisme sur les œuvres des auteurs qui écrivent soit de la Chine continentale soit d’outre-mer, et qui s’expriment à travers des langues différentes.