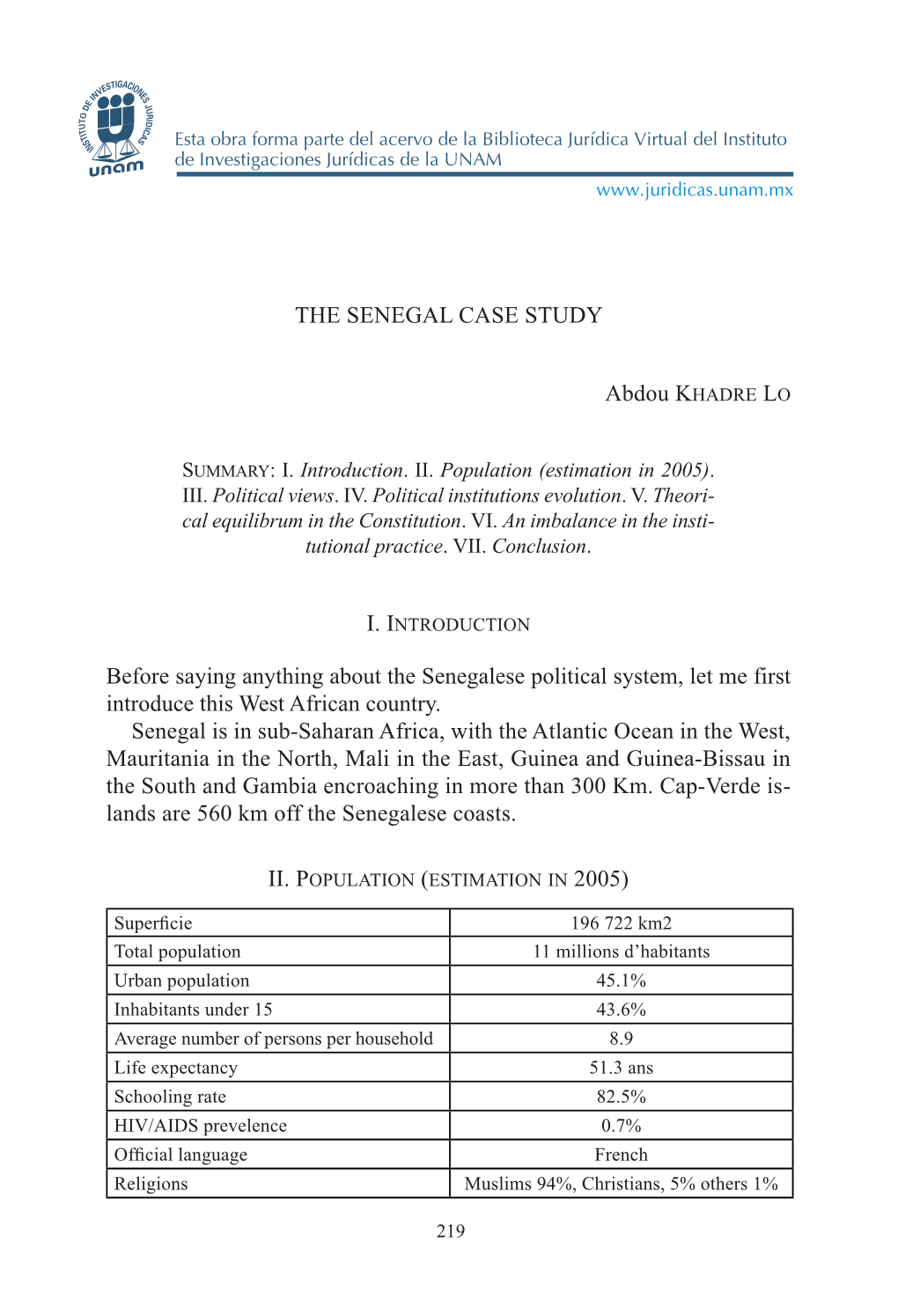

THE SENEGAL CASE STUDY Abdou KHADRE LO Before Saying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal

1 Democratization and Universal Health Coverage: A Case Comparison of Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal Karen A. Grépin and Kim Yi Dionne This article identifies conditions under which newly established democracies adopt Universal Health Coverage. Drawing on the literature examining democracy and health, we argue that more democratic regimes – where citizens have positive opinions on democracy and where competitive, free and fair elections put pressure on incumbents – will choose health policies targeting a broader proportion of the population. We compare Ghana to Kenya and Senegal, two other countries which have also undergone democratization, but where there have been important differences in the extent to which these democratic changes have been perceived by regular citizens and have translated into electoral competition. We find that Ghana has adopted the most ambitious health reform strategy by designing and implementing the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS). We also find that Ghana experienced greater improvements in skilled attendance at birth, childhood immunizations, and improvements in the proportion of children with diarrhea treated by oral rehydration therapy than the other countries since this policy was adopted. These changes also appear to be associated with important changes in health outcomes: both infant and under-five mortality rates declined rapidly since the introduction of the NHIS in Ghana. These improvements in health and health service delivery have also been observed by citizens with a greater proportion of Ghanaians reporting satisfaction with government handling of health service delivery relative to either Kenya or Senegal. We argue that the democratization process can promote the adoption of particular health policies and that this is an important mechanism through which democracy can improve health. -

Haiti: Concerns After the Presidential Assassination

INSIGHTi Haiti: Concerns After the Presidential Assassination Updated July 19, 2021 Armed assailants assassinated Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in his private home in the capital, Port-au- Prince, early on July 7, 2021 (see Figure 1). Many details of the attack remain under investigation. Haitian police have arrested more than 20 people, including former Colombian soldiers, two Haitian Americans, and a Haitian with long-standing ties to Florida. A Pentagon spokesperson said the U.S. military helped train a “small number” of the Colombian suspects in the past. Protesters and opposition groups had been calling for Moïse to resign since 2019. The assassination’s aftermath, on top of several preexisting crises in Haiti, likely points to a period of major instability, presenting challenges for U.S. policymakers and for congressional oversight of the U.S. response and assistance. The Biden Administration requested $188 million in U.S. assistance for Haiti in FY2022. Congress has previously held hearings, and the cochair of the House Haiti Caucus made a statement on July 7 suggesting reexaminations of U.S. policy options on Haiti. Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov IN11699 CRS INSIGHT Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Congressional Research Service 2 Figure 1. Haiti Source: CRS. Succession. Who will succeed Moïse is unclear, as is the leadership of the Haitian government. In the assassination’s immediate aftermath, interim Prime Minister Claude Joseph was in charge, recognized by U.S. and U.N. officials, and said the police and military were in control of Haitian security. Joseph became interim prime minister in April 2021. -

Urban Guerrilla Poetry: the Movement Y' En a Marre and the Socio

Urban Guerrilla Poetry: The Movement Y’ en a Marre and the Socio-Political Influences of Hip Hop in Senegal by Marame Gueye Marame Gueye is an assistant professor of African and African diaspora literatures at East Carolina University. She received a doctorate in Comparative Literature, Feminist Theory, and Translation from SUNY Binghamton with a dissertation entitled: Wolof Wedding Songs: Women Negotiating Voice and Space Trough Verbal Art . Her research interests are orality, verbal art, immigration, and gender and translation discourses. Her most recent article is “ Modern Media and Culture: Speaking Truth to Power” in African Studies Review (vol. 54, no.3). Abstract Since the 1980s, Hip Hop has become a popular musical genre in most African countries. In Senegal, young artists have used the genre as a mode of social commentary by vesting their aesthetics in the culture’s oral traditions established by griots. However, starting from the year 2000, Senegalese Hip Hop evolved as a platform for young people to be politically engaged and socially active. This socio-political engagement was brought to a higher level during the recent presidential elections when Hip Hop artists created the Y’En a Marre Movement [Enough is Enough]. The movement emerged out of young people’s frustrations with the chronic power cuts that plagued Senegal since 2003 to becoming the major critic of incumbent President Abdoulaye Wade. Y’en Marre was at the forefront of major demonstrations against Wade’s bid for a contested third term. But of greater or equal importance, the movement’s musical releases during the period were specifically aimed at “bringing down the president.” This article looks at their last installment piece entitled Faux! Pas Forcé [Fake! Forced Step or Don’t! Push] which was released at the eve of the second round of voting. -

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

Lesotho | Freedom House

Lesotho | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/lesotho A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 10 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. King Letsie III serves as the ceremonial head of state. The prime minister is head of government; the head of the majority party or coalition automatically becomes prime minister following elections, making the prime minister’s legitimacy largely dependent on the conduct of the polls. Thomas Thabane became prime minister after his All Basotho Convention (ABC) won snap elections in 2017. Thabane, a fixture in the country’s politics, had previously served as prime minister from 2012–14, but spent two years in exile in South Africa amid instability that followed a failed 2014 coup. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The lower house of Parliament, the National Assembly, has 120 seats; 80 are filled through first-past-the-post constituency votes, and the remaining 40 through proportional representation. The Senate—the upper house of Parliament—consists of 22 principal chiefs who wield considerable authority in rural areas and whose membership is hereditary, along with 11 other members appointed by the king and acting on the advice of the Council of State. Members of both chambers serve five- year terms. In 2017, the coalition government of Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili—head of the Democratic Congress (DC)—lost a no-confidence vote. The development triggered the third round of legislative elections held since 2012. -

Political Spontaneity and Senegalese New Social Movements, Y'en a Marre and M23: a Re-Reading of Frantz Fanon 'The Wretched of the Earth"

POLITICAL SPONTANEITY AND SENEGALESE NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, Y'EN A MARRE AND M23: A RE-READING OF FRANTZ FANON 'THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH" Babacar Faye A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Dalton Anthony Jones © 2012 Babacar Faye All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor This project analyzes the social uprisings in Senegal following President Abdoulaye Wade's bid for a third term on power. From a perspectivist reading of Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth and the revolutionary strategies of the Algerian war of independence, the project engages in re-reading Fanon's text in close relation to Senegalese new social movements, Y'en A Marre and M23. The overall analysis addresses many questions related to Fanonian political thought. The first attempt of the project is to read Frantz Fanon's The Wretched from within The Cultural Studies. Theoretically, Fanon's "new humanism," as this project contends, can be located between transcendence and immanence, and somewhat intersects with the political potentialities of the 'multitude.' Second. I foreground the sociogeny of Senegalese social movements in neoliberal era of which President Wade's regime was but a local phase. Recalling Frantz Fanon's critique of the bourgeoisie and traditional intellectuals in newly postindependent African countries, I draw a historical continuity with the power structures in the postcolonial condition. Therefore, the main argument of this project deals with the critique of African political leaders, their relationship with hegemonic global forces in infringing upon the basic rights of the downtrodden. -

Senegal | Freedom House

4/8/2020 Senegal | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Senegal 71 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 29 /40 Civil Liberties 42 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 72 /100 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. https://freedomhouse.org/country/senegal/freedom-world/2020 1/16 4/8/2020 Senegal | Freedom House Status Change Senegal’s status declined from Free to Partly Free because the 2019 presidential election was marred by the exclusion of two major opposition figures who had been convicted in politically fraught corruption cases and were eventually pardoned by the incumbent. Overview Senegal is one of Africa’s most stable electoral democracies and has undergone two peaceful transfers of power between rival parties since 2000. However, politically motivated prosecutions of opposition leaders and changes to the electoral laws have reduced the competitiveness of the opposition in recent years. The country is known for its relatively independent media and free expression, though defamation laws continue to constrain press freedom. Other ongoing challenges include corruption in government, weak rule of law, and inadequate protections for the rights of women and LGBT+ people. Key Developments in 2019 In February, President Macky Sall won a second consecutive term with 58 percent of the vote in the first round, making a runoff unnecessary. Two leading opposition leaders—Khalifa Sall, former mayor of Dakar, and Karim Wade, the son of former president Abdoulaye Wade—were barred from running because of previous, politically fraught convictions for embezzlement of public funds. In May, lawmakers approved a measure to abolish the post of prime minister, and Sall signed it later in the month. -

Workshop Report

WORKSHOP OF THE FRANCOPHONE AFRICAN ALLIANCE FOR WATER AND SANITATION Mbour - Saly Portudal (Senegal), 18-22 June 2019 WORKSHOP REPORT Minutes Workshop 8 Water and sanitation CSOs from West and Central Africa June 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Opening of the Workshop ............................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Sharing experiences on citizen control and accountability for SDG6 ................................... 4 1. Progress of the action plans of the CSOs elaborated in workshop 7 and follow-up to the studies on accountability mechanisms in the countries ................................................................................... 4 2. Focus on the Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) Partnership: Feedback from the Sector Ministers' Meeting (April 2019, Costa Rica) .....................................................................................................6 3. Presentation of the Watershed program / Mali ..............................................................................9 Part 2: Strategic workshop "On the way to Dakar 2021: Mobilizing WASH NGOs/CSOs in the Sub- region to achieve the SDG6" ........................................................................................................ 10 1. Preparation of the kick-off meeting of the 9th World Water Forum ........................................... 10 2. Session on a sub-regional strategy for African NGOs for the 9th WWF and beyond .................... 17 3. Kick off meeting of the 9th -

Senegal#.Vxcptt2rt8e.Cleanprint

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2015/senegal#.VXCptt2rT8E.cleanprint Senegal freedomhouse.org Municipal elections held in June 2014 led to some losses by ruling coalition candidates in major urban areas; the elections were deemed free and fair by local election observers. A trial against Karim Wade, son of former president Abdoulaye Wade, began in July in the Court of Repossession of Illegally Acquired Assets (CREI), where he is accused of illicit enrichment. Abdoulaye Wade, who had left Senegal after losing the 2012 presidential election, returned in the midst of the CREI investigation in April. The Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS), which he founded in 1974, requested permission to publicly assemble upon his return, but authorities denied the request. In February, Senegal drew criticism for the imprisonment of two men reported to have engaged in same-sex relations. The detentions of rapper and activist Malal Talla and of former energy minister Samuel Sarr in June and August, respectively, also evoked public disapproval; both men were detained after expressing criticism of government officials. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 33 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 11 / 12 Members of Senegal’s 150-seat National Assembly are elected to five-year terms; the president serves seven-year terms with a two-term limit. The president appoints the prime minister. In July 2014, President Macky Sall appointed Mohammed Dionne to this post to replace Aminata Touré, who was removed from power after losing a June local election in Grand-Yoff. The National Commission for the Reform of Institutions (CNRI), an outgrowth of a consultative body that engaged citizens about reforms in 2008–2009, presented a new draft constitution to Sall in February. -

Lesotho's Constitution of 1993 with Amendments Through 1998

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:37 constituteproject.org Lesotho's Constitution of 1993 with Amendments through 1998 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:37 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE KINGDOM AND ITS CONSTITUTION . 8 1. The Kingdom and its territory . 8 2. The Constitution . 8 3. Official languages, National Seal, etc. 8 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 8 4. Fundamental human rights and freedoms . 8 5. Right to life . 9 6. Right to personal liberty . 10 7. Freedom of movement . 11 8. Freedom from inhuman treatment . 13 9. Freedom from slavery and forced labour . 13 10. Freedom from arbitrary search or entry . 14 11. Right to respect for private and family life . 14 12. Right to fair trial, etc. 15 13. Freedom of conscience . 17 14. Freedom of expression . 18 15. Freedom of peaceful assembly . 18 16. Freedom of association . 19 17. Freedom from arbitrary seizure of property . 19 18. Freedom from discrimination . 21 19. Right to equality before the law and the equal protection of the law . 23 20. Right to participate in government . 23 21. Derogation from fundamental human rights and freedoms . 23 22. Enforcement of protective provisions . 24 23. Declaration of emergency . 25 24. Interpretation and savings . 25 CHAPTER III: PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 26 25. Application of the principles of State policy . 26 26. Equality and justice . 26 27. Protection of health . 27 28. Provision for education . -

Haiti on the Brink: Assessing US Policy Toward a Country in Crisis

“Haiti on the Brink: Assessing U.S. Policy Toward a Country in Crisis” Prepared Testimony Before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, Civilian Security, and Trade Daniel P. Erikson Managing Director, Blue Star Strategies Senior Fellow, Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement December 10, 2019 I begin my testimony by thanking Chairman Sires, Ranking Member Rooney, and the members of this distinguished committee for the opportunity to testify before you today about the current situation in Haiti – and to offer some ideas on what needs to be done to address the pressing challenges there. It is an honor for me to be here. I look forward to hearing from the committee and my fellow panelists and the subsequent discussion. The testimony that I provide you today is in my personal capacity. The views and opinions are my own, informed by my more than two decades of experience working on Latin American and Caribbean issues, including a longstanding engagement with Haiti that has included more than a dozen trips to the country, most recently in November 2019. However, among the other institutions with which I am affiliated, I would like to also acknowledge the Inter- American Dialogue think-tank, where I worked on Haiti for many years and whose leadership has encouraged my renewed inquiry on the political and economic situation in Haiti. My testimony today will focus on two areas: (1) a review of the current situation in Haiti; and (2) what a forward-leaning and constructive response by the United States and the broader international community should look like in 2020. -

Unicameralism and the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 Val Nolan, Jr.*

DOCUMENT UNICAMERALISM AND THE INDIANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1850 VAL NOLAN, JR.* Bicameralism as a principle of legislative structure was given "casual, un- questioning acceptance" in the state constitutions adopted in the nineteenth century, states Willard Hurst in his recent study of main trends in the insti- tutional development of American law.1 Occasioning only mild and sporadic interest in the states in the post-Revolutionary period,2 problems of legislative * A.B. 1941, Indiana University; J.D. 1949; Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Uni- versity School of Law. 1. HURST, THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN LAW, THE LAW MAKERS 88 (1950). "O 1ur two-chambered legislatures . were adopted mainly by default." Id. at 140. During this same period and by 1840 many city councils, unicameral in colonial days, became bicameral, the result of easy analogy to state governmental forms. The trend was reversed, and since 1900 most cities have come to use one chamber. MACDONALD, AmER- ICAN CITY GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 49, 58, 169 (4th ed. 1946); MUNRO, MUNICIPAL GOVERN-MENT AND ADMINISTRATION C. XVIII (1930). 2. "[T]he [American] political theory of a second chamber was first formulated in the constitutional convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 and more systematically developed later in the Federalist." Carroll, The Background of Unicameralisnl and Bicameralism, in UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURES, THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL DEBATE HAND- BOOK, 1937-38, 42 (Aly ed. 1938). The legislature of the confederation was unicameral. ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, V. Early American proponents of a bicameral legislature founded their arguments on theoretical grounds. Some, like John Adams, advocated a second state legislative house to represent property and wealth.