Democracy and Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

040 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books Mn. VVI LCI AM S1I .A. K- li- S 1^ -A. 1^. t/ S COMEDIES, HISTORICS, & TRAGED1E S. Pulliihid accorv LO 0 Priqtedty like laggard, aod Ed.Blount. 1 <5i}- Facsimile of the title-page of the First Folio Shakespeare, dated 1623 From the original in the New York Public Library, New York THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME I From Chaucer to Gray W//A Introductions and Notes Volume 40 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1910 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. S. A. CONTENTS GEOFFREY CHAUCER PAGE THE PROLOGUE TO THE CANTERBURY TALES n THE NUN'S PRIEST'S TALE 34 TRADITIONAL BALLADS THE DOUGLAS TRAGEDY 51 THE TWA SISTERS 54 EDWARD 5 6 BABYLON: OR, THE BONNIE BANKS O FORDIE 58 HIND HORN 59 LORD THOMAS AND FAIR ANNET 61 LOVE GREGOR 65 BONNY BARBARA ALLAN 68 THE GAY GOSS-HAWK 69 THE THREE RAVENS 73 THE TWA CORBIES 74 SIR PATRICK SPENCE 74 THOMAS RYMER AND THE QUEEN OF ELFLAND 76 SWEET WILLIAM'S GHOST 78 THE WIFE OF USHER'S WELL 80 HUGH OF LINCOLN 81 YOUNG BICHAM 84 GET UP AND BAR THE DOOR 87 THE BATTLE OF OTTERBURN 88 CHEVY CHASE 93 JOHNIE ARMSTRONG 101 CAPTAIN CAR 103 THE BONNY EARL OF MURRAY 107 KINMONT WILLIE ' 108 BONNIE GEORGE CAMPBELL 114 THE DOWY HOUMS O YARROW 115 MARY HAMILTON 117 THE BARON OF BRACKLEY 119 BEWICK AND GRAHAME 121 A GEST OF ROBYN HODE 128 1 2 CONTENTS ANONYMOUS PAG* BALOW 186 THE OLD CLOAK 188 JOLLY GOOD ALE AND OLD .. -

English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study

British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Vol.11 No.I (2012) ©BritishJournal Publishing, Inc. 2012 http://www.bjournal.co.uk/BJASS.aspx English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study Elmas Sahin Assist. Prof. Elmas Sahin, Cag University, The Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkey, [email protected], Tel: +90 324 651 48 00, fax: +90 324 651 48 11 Abstract Although "ballad" whose origins based on the medieval period in the Western World; derived from Latin, and Italian word 'ballata' (ballare :/ = dance) to “turku” occurring approximately in the same centuries in the Eastern World, whose sources of the'' Turkish'' word sung by melodies in spoken tradition of Anatolia, a term given for folk poetry /songs "Turks" emerged in different nations and different cultures appear in similar directions. When both Ballads and folk songs as products of different cultures in terms of topics, motifs, structures and forms were analyzed are similar in many respects despite of exceptions. Here we will handle and evaluate the ballads and turkus, folk songs, being the products of different countries and cultures, according to the Comparative Literature and Criticism, and its theory by focusing the selected works, by means of a pluralistic approach. In this context these two literary genres having literary values, similar and different aspects in structure and content will be evaluated compared and contrasted in light of various methods as formal ,structural, reception and historical approaches. Keywords: ballad, turku, folk songs, folk poems, comparative literature 33 British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Introduction Although both Ballad and Türkü are the products of different countries and cultures, except for some unimportant differences, they have similar aspects in terms of their subject, theme, motive, structure and form. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers</H1>

From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers From Chaucer to Tennyson by Henry A. Beers Juliet Sutherland, Sjaani and PG Distributed Proofreaders Chautauqua Reading Circle Literature FROM CHAUCER TO TENNYSON WITH TWENTY-NINE PORTRAITS AND SELECTIONS FROM THIRTY AUTHORS. BY page 1 / 403 HENRY A. BEERS _Professor of English Literature in Yale University_. [Illustration] PREFACE. In so brief a history of so rich a literature, the problem is how to get room enough to give, not an adequate impression--that is impossible--but any impression at all of the subject. To do this I have crowded out every thing but _belles lettres_. Books in philosophy, history, science, etc., however important in the history of English thought, receive the merest incidental mention, or even no mention at all. Again, I have omitted the literature of the Anglo-Saxon period, which is written in a language nearly as hard for a modern Englishman to read as German is, or Dutch. Caedmon and Cynewulf are no more a part of English literature than Vergil and Horace are of Italian. I have also left out the vernacular literature of the Scotch before the time of Burns. Up to the date of the union Scotland was a separate kingdom, and its literature had a development independent of the English, though parallel with it. In dividing the history into periods, I have followed, with some modifications, the divisions made by Mr. Stopford Brooke in his excellent little _Primer of English Literature_. A short reading course page 2 / 403 is appended to each chapter. HENRY A. -

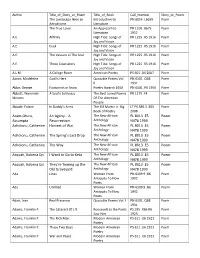

Acam-Oturu, Assumpta an Agony… a Resurrection PL 8013 .E5 N478

Author Title_of_Story_or_Poem Title_of_Book Call_Number Story_or_Poem The Landscape Near an Introduction to PN 6014 .L6659 Poem Aerodrome Literature The True Lover An Approach to PR 1109 .B675 Poem Literature 1952 A.E. Affinity High Tide: Songs of PR 1225 .R5 1916 Poem Joy and Vision A.E. Dusk High Tide: Songs of PR 1225 .R5 1916 Poem Joy and Vision A.E. The Vesture of The Soul High Tide: Songs of PR 1225 .R5 1916 Poem Joy and Vision A.E. Three Counselors High Tide: Songs of PR 1225 .R5 1916 Poem Joy and Vision A.L.M. A College Room American Poetry PS 601 .A4 2007 Poem Aaron, Madeleine God Is Here Quotable Poems Vol. PN 6101 .Q68 Poem II 1931 Abbe, George Footprints in Snow Poetry Awards 1950 PN 6101 .P6 1950 Poem Abbott, Wenonah A Soul’s Soliloquy The Best Loved Poems PR 1175 .F4 Poem Stevens Of The American People Abiade, Folami In Daddy’ s Arms The Bill Martin Jr. Big LT PS 586.3 .B55 Poem Book of Poetry 2008 Acam-Oturu, An Agony… A The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Assumpta Resurrection Anthology N478 1999 Acholonu, Catherine Harvest of War The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Anthology N478 1999 Acholonu, Catherine The Spring’s Last Drop The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Anthology N478 1999 Acholonu, Catherine The Way The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Anthology N478 1999 Acquah, Kobena Eyi I Want to Go to Keta The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Anthology N478 1999 Acquah, Kobena Eyi They’re Tearing up the The New African PL 8013 .E5 Poem Old Graveyard Anthology N478 1999 Ada Lines Women From PN 6109.9 .B6 Poem Antiquity To Now 1992 Poets Ada Untitled Women From PN 6109.9 .B6 Poem Antiquity To Now 1992 Poets Adair, Ivan Real Presence Quotable Poems Vol. -

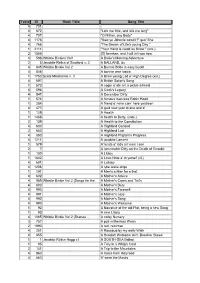

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Norton Anthology of Poetry THIRD EDITION

THE Norton Anthology of Poetry THIRD EDITION •?»-»?-3»KC-K(-KC-Cg{-{C{-KC-KfrKfrC«-K0«C-CCCCCC-«{-CgC-K{-C«-C«-K0C«-«0C<0«fr ALEXANDER W. ALLISON LATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HERBERT BARROWS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CAESAR R. BLAKE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO ARTHUR J. CARR WILLIAMS COLLEGE ARTHUR M. EASTMAN VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY HUBERT M. ENGLISH, JR. UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN With an essay on versification by Jon Stallworthy, Cornell University VTNWVT? W W NORTON & COMPANY New York • London Contents PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION xi Note on the Modernizing of Medieval Texts xiii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiv ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES 3 Now Go'th Sun Under Wood 3 The Cuckoo Song 3 Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerunt? 3 Alison 5 GEOFFREY CHAUCER (ca. 1343-1400) 6 THE CANTERBURY TALES 6 The General Prologue 6 The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale 24 The Introduction 24 The Prologue 25 The Tale 27 The Epilogue 36 The Nun's Priest's Tale 37 LYRICS AND OCCASIONAL VERSE 49 To Rosamond 49 Truth 49 Complaint to His Purse 50 Against Women Unconstant 51 Merciless Beauty 51 CHARLES D'ORLfiANS (1391-1465) 52 The Smiling Mouth 52 Oft in My Thought 53 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY 53 Adam Lay I-bounden 53 I Sing of a Maiden 54 Out of Your Sleep Arise and Wake 54 xv xvi Contents This Endris Night 55 I Have a Young Sister 56 I Have a Gentle Cock 57 Jolly Jankin 57 Timor Mortis 58 The Corpus Christi Carol 59 The Jolly Juggler 59 Western Wind 61 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 61 Jolly Good Ale and Old 61 WILLIAM DUNBAR (ca. -

The Child Ballad in Canada: a Survey1

THE CHILD BALLAD IN CANADA: A SURVEY1 LAUREL DOUCETTE and COLIN QUIGLEY While many folklorists might find the tabulation of Child ballad statistics a tedious and somewhat anachronistic exercise, few would deny the historical value of describing in detail the results of one phase of Canadian folksong research. It is our contention, however, that such an exercise serves deeper scholarly concerns. As an examination of a regional classical ballad repertoire, this survey provides a base for comparison with other regions. Given the broad geographic distribution and time depth represented by this genre, the Child ballads are well suited for such comparative study. More over, as the oldest level of the Anglo-Canadian song tradition, the national Child ballad repertoire forms an important base for folk song study within this country. An examination of maintenance and loss of story types within the Child corpus, as well as analysis of transformations undergone by individual ballads, could reveal culturally-specific concerns which may be reflected throughout the entire Canadian folksong repertoire. In addressing this topic, we have very little to go on other than the recorded corpus of material, for most song collections were made before the concept of “context” was introduced to folklore field research. The corpus, however, is substantial, and bears close examination in terms of its composition, distribution, and narrative style. Throughout this paper, when we use the term “ballad,” we mean “Child ballad” ; and we use the titles adopted by Child, followed by the number assigned by him.2 Ballad Research in Canada The earliest record of a British traditional ballad in Canada dates to 1898 when Phillips Barry published a text of “The Gypsy Laddie” (Ch 200) collected in Nova Scotia.3 In 1910 and 1912, W. -

The Ballad Book a Selection of the Choicest

THE BALLAD BOOK A SELECTION OF THE CHOICEST WILLIAM ALLINGHAM The Old Ballads' suggests as distinct a set of impressions as the name of Shakspeare, Spenser, or Chaucer ; but on looking close we find ourselves puzzled ; the sharp bounding lines disappear the mountain chain so definite on the horizon is found to be a disunited and intricate region. Perhaps most people's notion of the Old Ballads is formed out of recollections of Percy's Reliques Ritson's Robin Hood set, Scott's Border Minstrelsy as re- positories ; of ' Sir Patrick Spens,' Clerk Saunders,'tions, dissertations, notes, appendices, commenta- ries, controversies, of an antiquarian, historical, or pseudo-historical nature, wherein the poetry is packed, like pots of dainties and wine-flasks in straw and sawdust. In most of the collections, lyrics and metrical tales are associated with the Ballads proper, and it has been usual, besides, to load on a heap of Modern Imitations. All honour and gratitude to the collectors and editors, greater and lesser ; (yet one must venture to say that the really fine and favourite Old Ballads have hitherto formed the vital portions of a set of volumes which are, on the whole, rather lumpish and unreadable. The feast they offer is somewhat like an olla podrida' of Spenser's Fairy Queen, Dodsles Miscellany the driest columns of Notes and Queries, and a selection from the Poet's Comer of the provincial newspapers. The Ballads which we give have, one and all, no connection of the slightest importance with history. , Things that did really happen are no doubt shadowed forth in many of them, but with such a careless confu- sion of names, places, and times, now thrice and thirty .times confounded by alterations in course of oral transmission, vaiious versions, personal and local adaptations, not to speak of editorial emendations, that it is mere waste of time and patience to read (if any one ever does read) those grave disquisitions, historical and antiquarian, wherewith it has been the fashion to encumber many of these rudely pictu- resque and pathetic poems. -

Discography Section 14: Ma-Mckay (PDF)

1 NOTE: Because of the indiscriminate and random spelling, all surnames starting with M’, Mc, Mac are listed by the following letter. ANDREW MAC “Scotch comic” (born Bannockburn) Recorded London, ca March 1905 2658 Killiecrankie (Harry Lauder) Odeon 2658/2660(7½”) 2660 Hooch Aye (William F. Frame) Odeon 2660/2658, 2660/2754, 3246(7½”) 2695 Stop yer ticklin’ Jock (Frank Folloy; Harry Lauder) Odeon 2695/2753(7½”) 2746 The piper (William F. Frame) Odeon 2746/2750, 3247(7½”) 2750 Jericho (Alex Melville; Harry Lauder) Odeon 2750/2746(7½”) 2753 Sandy McPherson (Andrew Mac) Odeon 2753/2695(7½”) 2754 Fairly gone (Barrett) Odeon 2754/2660(7½”) Recorded London, ca December 1905 Daisy (Jack D. Harper; Harry Lauder) Odeon 32626/32600, 441(10¾”) Tak’ it home (Andrew Mac) Odeon 32600/32626, 441 (10¾”) I love a lassie (Gerald Grafton; Harry Lauder) Odeon 44264/44263, 537(10¾”) Stop yer ticklin’ Jock (Frank Folloy; Harry Lauder) Odeon 44263/44264, 537(10¾”) JAMES McALLISTER Pseudonym on Scala 427 for Sandy Glen HECTOR MacANDREW (Fyvie, 1903 – 1980). Violin, piano accompaniment by Pat MacAndrew Recorded Orpheus Studio, Greyfriars Church Hall, Albion Street, Glasgow, Thursday, 24th. April 1952 CE-14024-1 The Laird o’ Bemersyde (heroic pastoral); Sandie Cameron (strathspey); Forbes Morrison (strathspey); The left handed fiddler (reel) (all by J. Scott Skinner) Par F-3466 CE-14025-2 Scottish Country Dance Medley – part 1 – Intro. The Dean brig o’ Edinburgh, slow strathspey (Archie Allen); The Dean Brig reel (Peter Milne); Banks hornpipe (classical hornpipe) (Parazotti) Par F-3446 CE-14026-1 Scottish Country Dance Medley – part 2 – Intro. -

The Harvard Classics Eboxed

01119 BBiai W' •*'«i=:^^--r^: -^---.Vii.S. «-.--,-««.. ..-v«i,V> DQI THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books SHAKESPEARESMr.VV! LL1AA4 t;oAjr.i)iES, HISTORIES, & Til AG 1.1)1 hS. ^:!'-,'li.l!i Copies. ' L P^D .'X^ TnqtiA by Ifaac laggard, and Ed. Bl ount, 1 6 x ;• Facsimile of the title-fage of the First Folio Shakes-peare, dated t62^ From the original in the New York Public Library, Neto York THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME I From Chaucer to Gray W/VA Introductions and l>iotes Volume 40 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, igio By p. F. Collier & Son manufactured in u. s. a. CONTENTS Geoffrey Chaucer page The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales ii The Nun's Priest's Tale 34 Traditional Ballads The Douglas Tragedy 5^ The Twa Sisters 54 Edward 56 Babylon: or. The Bonnie Banks o Fordie 58 Hind Horn 59 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet 61 Love Gregor 65 Bonny Barbara Allan 68 The Gay Goss-Hawk 69 The Three Ravens 73 The Twta Corbies 74 Sir Patrick Spence 74 Thomas Rymer and the Queen of Elfland 76 Sweet William's Ghost 78 The Wife of Usher's Well 80 Hugh of Lincoln 81 Young Bicham 84 Get Up and Bar the Door 87 The Battle of Otterburn 88 Chevy Chase 93 Johnie Armstrong loi Captain Car 103 The Bonny Earl of Murray 107 Kinmont Willie • 108 Bonnie George Campbell . 114 The Dowy Houms o Yarrow 115 Mary Hamilton 117 The Baron of Brackley 119 Bewick and Grahame 121 A Gest of Robyn Hode 128 I 2 CONTENTS Anonymous pao« Balow i86 The Old Cloak i88 Jolly Good Ale and Old .. -

String Orchestra

String Orchestra Title Composer Catalog # Grade Price Title Composer Catalog # Grade Price Φ A La Manana ....................................../Leidig; Niehaus ............49063 .....E .........45.00 + A-Flat (Black Violin) ............................/Moore ..........................69940 .....M.........50.00 + Abandoned Funhouse ........................Balmages .....................64889 .....E .........45.00 African Accents ................................../Shapiro ........................38733 .....M.........52.00 Abandoned Treasure Hunt .................Grice .............................70719 .....ME ......40.00 African Adventure ...............................Sheldon ........................35802 .....ME ......46.00 Abdelazer: Rondeau ..........................Purcell/Doan .................40594 .....M.........25.00 African Serenade ...............................Pancarowicz .................56568 .....ME ......45.00 Abdelazer: Rondo (Moor's Revenge)...Purcell/Phillips ..............70502 .....ME ......45.00 An African-American Air (Oh, Abdelazer: Rondo ..............................Purcell/Stroud ...............57557 .....MD ......40.00 Mother Glasco) ................................/Mixon ...........................30941 .....ME ......40.00 Abduction fr. the Seraglio: Ha! Wie Will ich Triumpieren After Dreams ......................................Rich, W. ........................59542 .....ME ......45.00 ...........................................................Mozart/Bailey ..............62547 .....M.........52.00 After Hours