The Solution-Focused Approach to Practice and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Test of an Auditory Motion Hypothesis for Continuous and Discrete Sounds Moving in Pitch Space

A TEST OF AN AUDITORY MOTION HYPOTHESIS FOR CONTINUOUS AND DISCRETE SOUNDS MOVING IN PITCH SPACE Molly J. Henry A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: J. Devin McAuley, Advisor Rodney M. Gabel Graduate Faculty Representative Jennifer Z. Gillespie Dale S. Klopfer ii ABSTRACT J. Devin McAuley, Advisor Ten experiments tested an auditory motion hypothesis, which proposes that regular pitch- time trajectories facilitate perception of and attention to auditory stimuli; on this view, listeners are assumed to use velocity information (pitch change per unit time) to generate expectations about the future time course of continuous and discrete sounds moving in pitch space. Toward this end, two sets of experiments were conducted. In six experiments reported in Part I of this dissertation, listeners judged the duration or pitch change of a continuous or discrete comparison stimulus relative to a standard, where the comparison’s velocity varied on each trial relative to the fixed standard velocity. Results indicate that expectations generated based on velocity information led to distortions in perceived duration and pitch change of continuous stimuli that were consistent with the auditory motion hypothesis; specifically, when comparison velocity was relatively fast, duration was overestimated and pitch change was underestimated. Moreover, when comparison velocity was relatively slow, duration was underestimated and pitch change was overestimated. On the other hand, no perceptual distortions were observed for discrete stimuli, consistent with the idea that velocity information is less clearly conveyed, or easier to ignore, for discrete auditory stimuli. -

An Approach to the Musical Analysis of Wind Band Literature Based on Analytical Modes Used by Wind Band Specialists and Music Theorists

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1995 An Approach to the Musical Analysis of Wind Band Literature Based on Analytical Modes Used by Wind Band Specialists and Music Theorists. Jerome Raymond Markoch Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Markoch, Jerome Raymond Jr, "An Approach to the Musical Analysis of Wind Band Literature Based on Analytical Modes Used by Wind Band Specialists and Music Theorists." (1995). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6030. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6030 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality o f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

BIOGRAPHIES of PRESENTERS & COMPOSERS Updated 10/23/17 Adler, Ayden Ayden Adler Is Dean of the Depauw University School of M

BIOGRAPHIES OF PRESENTERS & COMPOSERS updated 10/23/17 Adler, Ayden Ayden Adler is Dean of the Depauw University School of Music. In her previous role as dean of the New World Symphony, America’s Orchestral Academy, Dr. Adler redesigned the academic program to address 21st-century needs of music students by providing high-level training in audience engagement, community engagement, and digital engagement, musician health and wellness, entrepreneurship, and leadership development. Before working in higher education administration, Dr. Adler served as Executive Director of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra in New York City. With support from the Mellon Foundation, she expanded the Orpheus Institute, through which Orpheus musicians mentor the next generation of musicians and business leaders in shared leadership, entrepreneurship, and communication. Dr. Adler has also served as Director of Education and Community Partnerships for the Philadelphia Orchestra and as the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra’s Director for Learning Development. As an orchestral musician, Dr. Adler performed in many countries under esteemed conductors, including Loren Maazel, Mstislav Rostropovich, and Alan Gilbert. Alberti, Alexander Alexander Alberti is the current director of instrumental music and psychology at Longleaf School of the Arts in Raleigh, North Carolina. In addition, he works with the Middle Creek High School Marching Mustang Band, instructing front ensemble and percussion. Alberti formerly taught at Southern Lee High School in Sanford, North Carolina, where he directed band, orchestra, chorus, and an extracurricular a cappella program. Alberti is an active researcher in the field of music theory pedagogy and music education, presenting his findings at NAfME, CMS National, and NCUR. Alberti currently holds a Bachelors of Music in Music Education from Appalachian State University with a minor in Psychology. -

Capturing-Sound-How-Technology-Has-Changed-Music.Pdf

ROTH FAMILY FOUNDATION Music in America Imprint Michael P. Roth and Sukey Garcetti have endowed this imprint to honor the memory of their parents, Julia and Harry Roth, whose deep love of music they wish to share with others. This publication has been supported by a subvention from the Gustave Reese Publication Endowment Fund of the American Musicological Society. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Music in America Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Associates, which is supported by a major gift from Sukey and Gil Garcetti, Michael Roth, and the Roth Family Foundation. CAPTURING SOUND H O W CAPT T U E C R H N I O N L O G G Y S UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS H A S O C H U A N N G E D D M BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON U S I C tz mark ka University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England “The Entertainer” written by Billy Joel © 1974, JoelSongs [ASCAP]. All rights reserved. Used by permission. © 2004 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Katz, Mark, 1970–. Capturing sound : how technology has changed music / Mark Katz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24196-7 (cloth : alk. paper)— ISBN 0-520-24380-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Sound recording industry. 2. Music and technology. I. Title. ml3790.k277 2005 781.49—dc22 2004011383 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). -

The Only Common Thread: Race, Youth, and the Everyday Rebellion of Rock and Roll, Cleveland, Ohio, 1952-1966

THE ONLY COMMON THREAD: RACE, YOUTH, AND THE EVERYDAY REBELLION OF ROCK AND ROLL, CLEVELAND, OHIO, 1952-1966 DANA ARITONOVICH Bachelor of Arts in Communications Lake Erie College May, 2006 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 This thesis has been approved for the Department of HISTORY and the College of Graduate Studies by _____________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Karen Sotiropoulos ___________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________ Dr. David Goldberg ___________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Humphrey ___________________________ Department & Date THE ONLY COMMON THREAD: RACE, YOUTH, AND THE EVERYDAY REBELLION OF ROCK AND ROLL, CLEVELAND, OHIO, 1952-1966 DANA ARITONOVICH ABSTRACT This thesis is a social and cultural history of young people, race relations, and rock and roll music in Cleveland between 1952 and 1966. It explores how the combination of de facto segregation and rock and roll shaped attitudes about race for those coming of age after the Second World War. Population changes during the Second Great Migration helped bring the sound of southern black music to northern cities like Cleveland, and provided fertile ground for rock and roll to flourish, and for racial prejudice to be confronted. Critics blamed the music for violence, juvenile delinquency, and sexual depravity, among other social problems. In reality, the music facilitated racial understanding, and gave black and white artists an outlet through which they could express their hopes and frustrations about their lives and communities. Through the years, the music provided a window into the lives of “the other” that young Americans in a segregated environment might not otherwise experience. -

Light Music in the Practice of Australian Composers in the Postwar Period, C.1945-1980

Pragmatism and In-betweenery: Light music in the practice of Australian composers in the postwar period, c.1945-1980 James Philip Koehne Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide May 2015 i Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. _________________________________ James Koehne _________________________________ Date ii Abstract More than a style, light music was a significant category of musical production in the twentieth century, meeting a demand from various generators of production, prominently radio, recording, film, television and production music libraries. -

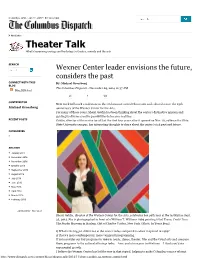

The Columbus Dispatch - November 09, 2014 12:37 AM Blog RSS Feed

Columbus, Ohio • Jan 11, 2017 • 53° Overcast Hot Links: What's happening onstage and backstage in theater, comedy and the arts SEARCH CONNECT WITH THIS By: Michael Grossberg BLOG The Columbus Dispatch - November 09, 2014 12:37 AM Blog RSS feed 41 7 105 CONTRIBUTOR Next week will mark a milestone in the evolution of central Ohio’s arts and cultural scene: the 25th Michael Grossberg anniversary of the Wexner Center for the Arts. For many of those years, Sherri Geldin has been thinking about the center’s distinctive mission and guiding its diverse creative possibilities to become realities. RECENT POSTS Geldin, director of the center for all but the first four years after it opened on Nov. 16, 1989 on the Ohio State University campus, has interesting thoughts to share about the center’s rich past and future. CATEGORIES ARCHIVE January 2017 December 2016 November 2016 October 2016 September 2016 August 2016 July 2016 June 2016 May 2016 April 2016 March 2016 February 2016 Advertisement • Place an ad Sherri Geldin, director of the Wexner Center for the Arts, celebrates her 20th year at the institution Sept. 25, 2013. She is photographed in front of a William T. Williams 1969 painting titled Trane, Credit Line: The Studio Museum in Harlem, Gift of Charles Cowles, New York. (Photo by Tessa Berg) Q What’s the biggest difference at the center today compared to when it opened in 1989? A There’s more contemporary, more vanguard programming. If you consider our key programs in 1989 in music, dance, theater, film and the visual arts and compare those programs to the cultural offerings today – here and at our peer institutions – I think you’d see exponential growth. -

November Concert Lawrence University Choirs Phillip A

November Concert Lawrence University Choirs Phillip A. Swan and Stephen M. Sieck, conductors Guest artist: Professor Carl Rath, bassoon Friday, November 15, 2019 8:00 p.m. Lawrence Memorial Chapel Please donate to Music for Food before leaving tonight! What is Music for Food? Music for Food believes both music and food are essential to human life and growth. Music has the power to call forth the best in us, inspiring awareness and action when artists and audiences work together to transform the ineffable into tangible and needed food resources. Music for Food is a musician-led initiative for local hunger relief. Our concerts raise resources and awareness in the fight against hunger, empowering all musicians who wish to use their artistry to further social justice. Donations of non-perishable food items or checks will be accepted at the door. All monetary donations are tax-deductible, and will be processed by the national office of Music for Food. 100% will be sent to the food pantry at St. Joseph’s. Each year the St. Joseph Food Program distributes thousands of pounds of food to those who are hungry in the Fox Valley. Lawrence is proud to help. Concert Choir As the Sunflower Turns on Her God Timothy C. Takach (b. 1978) Bianca Pratte, soloist Small Ensemble: Bianca Pratte, Rehanna Rexroat, Henry McCammond-Watts, Caro Granner, Tommy Dubnicka, Preston Parker, Baron Lam, Maxim Muter Gøta Peder Karlsson (b. 1963) Cum Sancto Spiritu from Gloria Hyo-Won Woo (b. 1974) Viking Bass Clef Ensemble Alleluia Andrew Steffen (b. 1990) Viking Chorale Fog Elna Khel arr. -

Introducing Music Therapy Techniques Into Early Years Special Needs Education for Young Children with Autism in China

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES School of Education Introducing Music Therapy Techniques into Early Years Special Needs Education for Young Children with Autism in China by Li Hao Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 ABSTRACT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES School of Education Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy INTRODUCING MUSIC THERAPY TECHNIQUES INTO EARLY YEARS SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION FOR YOUNG CHILDREN WITH AUTISM IN CHINA by Li Hao This research thesis explores the introduction of a musical intervention (Developing Communication Through Music, DCTM) for young children with autism in China. The intervention was designed to combine techniques from both music therapy and Intensive Interaction in order to support the development of children whose social communication and social abilities are impaired. There is evidence about the effectiveness of both these techniques in the UK and other countries, but no such evidence in China. This research therefore represents the first systematic exploration of an intervention combining music therapy with Intensive Interaction in the cultural context of China, where these techniques are rare and where teacher training for autism is under-developed. Using the established principles of action research this study aimed to explore how DCTM musical intervention could be implemented within the current educational system in one community centre. The action focused on the introduction of DCTM in two cycles, first with the DCTM implemented by the researcher (a music therapist) and the second implemented by local staff. The goal was to improve understanding of how music can be used to help young children with autism in tandem with brining about beneficial change for young children and the adults communicating with and teaching them. -

Mauro Scocco and Tomas Andersson Wij (Music)

From non-conformist escapist synth pop to bittersweet Italian melancholy and soothing Swedish sentimentality - the songs of Mauro Scocco and Tomas Andersson Wij (by J. Granström) One of the summer’s most anticipated tours was “Tomas Andersson Wij plays with Mauro Scocco”, which concluded with a celebrated concert at Stockholm’s Mosebacketerrassen on August 15th. Tomas Andersson Wij (TAW) and Mauro Scocco are two of Sweden’s most beloved singer/songwriters, and their catalogues include dozens of critically acclaimed and commercially successful albums as well as performances in front of millions of people on Swedish TV. However, Scocco and TAW were not always widely embraced by the Swedish music industry or the general public at the start of their careers in the 1980’s and 1990’s, respectively. In Scocco’s case, he signed his first record deal with his group Ratata - at the time consisting of Heinz Liljedahl, Anders Skog and Johan Kling - through young record executive Klas Lunding in 1981. At that time, Lunding was only 19 years old but had already released multiple albums and singles through his label Stranded Records. However, distribution agreements for Stranded’s releases were signed with the politically left-leaning progg movement - not to be confused with today’s contemporary progressive rock - requiring signees to commit to promoting a socialist revolution through their musical acts. On the surface, this did not align well with Ratata’s influences, which came from the world of fashion and commercials. However, media quickly showed an interest in both the packaging and musical novelty of Ratata as one of the first new Swedish synth pop bands of the 1980’s. -

Did the Recording Industryâ•Žs Shift From

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 2 Issue 3 Business Law as Public Interest Law / Article 12 Searching for Equality: A Conference on Law, Race, and Socio-Economic Class 12-2012 The Long-Playing Blues: Did the Recording Industry’s Shift from Singles to Albums Violate Antitrust Law? Jeffrey Philip Wachs UC Irvine School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey P. Wachs, The Long-Playing Blues: Did the Recording Industry’s Shift ofr m Singles to Albums Violate Antitrust Law?, 2 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 1047 (2012). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol2/iss3/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. UCILR V2I3 Assembled v8 (Do Not Delete) 12/14/2012 5:35 PM The Long-Playing Blues: Did the Recording Industry’s Shift from Singles to Albums Violate Antitrust Law? Jeffrey Philip Wachs* Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1048 I. Legal Background: Antitrust, Tying, and Block Booking of Copyrights ......... 1049 A. The Block-Booking Cases ......................................................................... 1051 B. The Blanket License: Broadcast Music, Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System .................................................................................... -

Composing the Party Line Music and Politics in Early Cold War Poland and East Germany Central European Studies Charles W

Composing the Party Line Music and Politics in Early Cold War Poland and East Germany Central European Studies Charles W. Ingrao, senior editor Gary B. Cohen, editor Franz Szabo, editor Daniel L. Unowsky, editor Composing the Party Line Music and Politics in Early Cold War Poland and East Germany David G. Tompkins Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2013 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tompkins, David G. Composing the Party Line: Music and Politics in Early Cold War Poland and East Germany / David G. Tompkins. pages cm. -- (Central European Studies series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-55753-647-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-61249-289-6 (epdf) -- ISBN 978-1-61249-290-2 (epub) 1. Music--Political aspects--Poland--His- tory--20th century. 2. Music--Political aspects--Germany (East)--History--20th century. 3. Music and state--Poland--History--20th century. 4. Music and state- -Germany (East)--History--20th century. I. Title. ML3916.T67 2013 780.943'109045--dc23 2013013467 Cover image: A student choir and folk music ensemble perform in Leipzig. The slogan reads: “Art can accomplish much in educating people about true patriotism and the spirit of peace, democracy, and progress” (SLUB Dresden / Abt. Deutsche Fotothek, Roger & Renate Rössing, 25 January 1952). 5IBOLTUPUIFTVQQPSUPGPWFSMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHUISPVHIUIF,OPXMFEHF 6OMBUDIFEQSPHSBN BOFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTNBEFBWBJMBCMFVOEFSB $SFBUJWF$PNNPOT $$#:/$ MJDFOTFGPSHMPCBMPQFOBDDFTT5IF*4#/PGUIF