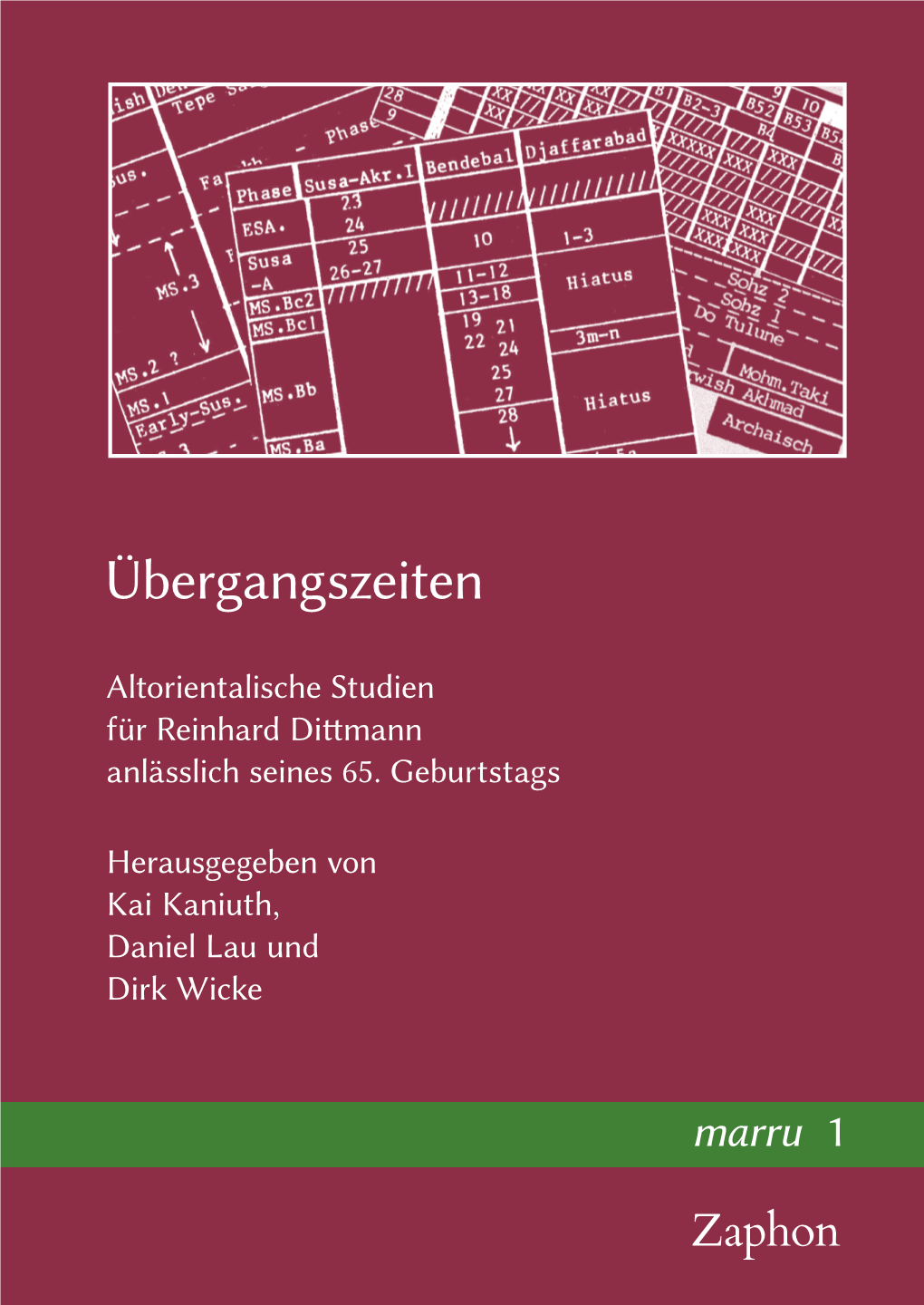

Übergangszeiten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September xx, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Desiree Zenowich Getty Communications (310) 440-7304 [email protected] MAGNIFICENT ASSYRIAN PALACE RELIEFS ON VIEW AT THE GETTY VILLA Masterworks on special loan from the British Museum in London Assyria: Palace Art of Ancient Iraq At the Getty Villa October 2, 2019–September 5, 2022 LOS ANGELES - In the ninth to seventh centuries B.C., the Assyrians, based in northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), forged a great empire that extended at its height from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and parts of Turkey in the west, through Iraq to the mountains of Iran and Armenia in the east. To glorify their reigns, the Assyrian rulers built Royal Lion Hunt, 875 - 860 B.C, Unknown. Assyrian. Gypsum Dimensions: Object: H: 95.8 Å~ W: 137.2 Å~ D: 20.3 cm (37 11/16 Å~ 54 Å~ 8 majestic palaces adorned with in.) British Museum [1849,1222.8] [1849]. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. Accession No. VEX.2019.2.1 relief sculptures that portray the king as a mighty warrior and hunter, and confront visitors with imposing images of winged bulls, demons and other mythological guardians. Assyria: Palace Art of Ancient Iraq, on view at the Getty Villa October 2, 2019 to September 5, 2022, presents a selection of these famous relief sculptures as a special loan from the British Museum in London. Among the greatest masterpieces of Mesopotamian art, th the Assyrian reliefs have, since their discovery in the mid-19 century, fascinated viewers with The J. -

Exploring How Narrative and Symbolic Art Impacts Artist, Researcher, Teacher and Communicates Meaning in Art to Students

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design Spring 5-10-2014 Exploring How Narrative and Symbolic Art Impacts Artist, Researcher, Teacher and Communicates Meaning in Art to Students Dorothy J. Eskew Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Eskew, Dorothy J., "Exploring How Narrative and Symbolic Art Impacts Artist, Researcher, Teacher and Communicates Meaning in Art to Students." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING HOW NARRATIVE AND SYMBOLIC ART IMPACTS ARTIST, RESEARCHER, TEACHER AND COMMUNICATES MEANING IN ART TO STUDENTS by DOROTHY J. ESKEW Under the Direction of Melody Milbrandt ABSTRACT This educational study on narrative and symbolic art and its impact on me as artist, re- searcher, and teacher and ultimately how the use of narrative and symbolism impacts student learning was conducted throughout the school year 2013-2014 in the environment of both my home and my classroom in a south metro Atlanta high school. The research is based on my re- flections of my artistic processes, my research of family history, and my observations as I intro- duced narrative and symbolic art in the classroom. The findings of the study reveal that the roles of artist, teacher, and researcher are signifi- cantly interrelated and enhance one another; I also believe that my students’ learning was im- pacted. -

Copyright by Breton Adam Langendorfer 2012

Copyright by Breton Adam Langendorfer 2012 The Thesis Committee for Breton Adam Langendorfer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Who Builds Assyria: Nurture and Control in Sennacherib’s Great Relief at Khinnis APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Nassos Papalexandrou Penelope Davies Who Builds Assyria: Nurture and Control in Sennacherib’s Great Relief at Khinnis by Breton Adam Langendorfer, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 “…how are we here, when the vessel in which we rode plunged down so long a tunnel?” He shrugged my question aside. “Why should gravity serve Urth when it can serve Typhon?” –Gene Wolfe, The Book of the New Sun Acknowledgements It is a privilege and a pleasure to thank the many people without whom this thesis could not have been written. First and foremost I wish to thank my advisor, Nassos Papalexandrou. His generosity, unflagging encouragement, and boundless intellectual curiosity have been a source of inspiration to me, and have enriched my future immeasurably. Penelope Davies has my deep thanks for her expert and invaluable reading of this work. I also wish to thank professors John R. Clarke, Stephennnie Mulder, Rabun Taylor, and especially Glenn Peers, who gave me the confidence to first enter the City of Ideas. Jessamine Batario, Taylor Bradley, Alex Grimley, Claire Howard, Jeannie McKetta, Jared Richardson and Margaret Wardlaw have all given me their warm friendship, humor, and support, and I am glad to have the opportunity to thank them for it. -

From Sequence to Scenario. the Historiography and Theory of Visual Narration

From Sequence to Scenario. The Historiography and Theory of Visual Narration Gyöngyvér Horváth Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of World Art Studies and Museology 2010 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. Abstract When visual narratives first became the focus of study in art history in the late nineteenth century, they were believed to be such a strong phenomenon that they effected the formation of styles. Today, visual narratives are regarded as significant forms of knowledge in their own right, appearing both within and beyond the artistic context. Between these two ideas there is a century-long story of historiography, an almost unknown tradition of academic writing. One of the major aims behind the research presented in this thesis is to trace this tradition: to show the main trends, ideas, persons and methods that formed this particular discourse. In the first part of the thesis, two fundamentally different traditions are identified: one where narratives were regarded as illustrations and one which treated them as elements of a visual language. Special attention has been devoted to the ideas of two scholars, G. E. Lessing and Franz Wickhoff. This is because Lessing’s ideas had particularly strong and lasting effects, and Wickhoff’s ideas were visionary and exemplary. -

Julian Reade IDEOLOGY and PROPAGANDA in ASSYRIAN ART

329 :u GAR-at KUR ana KI.KAL N1G1N fR GAL-ma KUR u-sa-ah-hi,' YOS l-ti-i-su dciR.uNu.GAL i-ih~ha-al III 2 KUN mes..lu GiRmes..su G1M sa Julian Reade DA KU LUGAL ,i-dan-nin;, 50': BE IDEOLOGY AND PROPAGANDA IN ASSYRIAN ART rGAL KAL-ma US4 KUR u-hal-Iaq. 26'; XVll, 16'; XXI, 1,43'; YOS X, .' un EN KALAG ravage Ie pays. This paper has two main themes: how the Assyrians viewed themselves 'Iia, 1977, 168 et mon commentaire and their relationship with the outside world, and how they wished 'erlands Histor, Inst, Istanbul. 1975, Miiller, MVAG. 41/3, 1937, 12.34: the outside world to view them. In considering what the official art of Assyria, which means above all the Assyrian sculptures, has to tell us ede La voi" de I'opposition en Meso. about these matters, I occasionally refer also to written documents. They and the sculptures are inseparable, like the print and pictures in an illus 2 bis, 280. trated book, but other contributors deal with the written evidence in greater detail.1 The historical background should first be summarized. Assyria was an ancient kingdom based in what is now northern Iraq. In the first half of the ninth century B.C. it expanded west and east by military conquest to cover an area stretching from the Euphrates, in Syria and Turkey, to the central Zagros, roughly the present frontier between Iraq and Iran. The bulk of this empire was a homogeneous area to much of which Assyria had traditional claims inherited from a comparable period of expansion in the past; it had a common economic basis of rain-fed agriculture, and was readily absorbed into Assyria proper so that, for instance, when the ern pire disintegrated, its last stronghold was in the far west at the city of Har ran. -

Curriculum Narrative: Art (Stibbard)

Curriculum Narrative: Art (Stibbard) Aut 1 Aut 2 Spr 1 Spr 2 Sum 1 Summer 2 Year 1 How do abstract What types of lines How can you How can I use How can I use What is weaving? artists use colour? can we use to manipulate paper printing to collage to show create a drawing to create a represent plants what I know about Techniques/ Techniques/ from the natural sculpture? and vegetables? the artist Matisse? materials: Textiles materials: : world. Weaving - plastic Painting - colour Go out into the Techniques/ Techniques/ bags, resauble colour mixing environment to materials: materials: Techniques/ Colour wheel- observe. Use Sculpture- form & Print materials: Collage, Vocab: primary colours ‘peephole squares’ space Copy Scale Texture and secondary to draw parts of Pattern Weave colours objects? Vocab: Repeat Vocab: Weft Sculpture Transfer Matisse Textile Vocab: Techniques/ Design Technique Collage over/under Primary materials: Make Observe Colour Recycle secondary Explore different Texture Sketch Shape Reuse Colours lines, Blind Alexander Cader Assemble Decorate abstract drawing, Construct Lottie Day Pattern Tint Continuous line Mobile Design Hue drawing Manipulate : Vocab: Abstract Artist: Shape Crayon wax resist Fold Print, copy, pattern, Scale Rothko Leaves, charcoal Twist repeat Collaboration Jo Athorton Mondrian Coloured pencil Roll Klee Drawing pencil, Curl Artist: Local artist - Artist: Matisse Text/hook: Artist wax crayons, kinesthetic Lottie Day Show : Artwork Painter brusho/paint Mix Artist: Alexander Text/hook Text/hook: -

Can One “Read” a Visual Work of Art?

Can one “read” a visual work of art? Estelle Alma Maré Department of Architecture, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria E-mail: mare_estelle”fastmail.fm Points of view are offered concerning the merit of the commonplace metaphorical reference to the “reading” of visual images or works of art as if they were, like language texts, composed of an underly- ing linguistic structure. In order to deliberate the question posed in the title of the article, the introduc- tory part deals with an issue in Western medieval art referring to the implications of the statement by Pope Gregory the Great that depictions of religious narratives on the walls of churches represent the Bible for the illiterate. A specific example, taken to be representative of medieval narrative art based on Biblical texts, is described to show that for the understanding of suchlike images by medieval viewers knowledge of the written texts as well as other literary information to which the representations refer was necessary. After conclusions had been drawn from this discussion a selection of contemporary theories that claim or deny that visual images and works of art can be “read” are reviewed, followed by two contradictory concluding remarks. The first is an insight by Ludwig Wittgenstein, that “Eve- rything is what it is and not another thing”. Thus, a visual work of art is a symbolic structure in its own right does not resemble a literary text. The second utilizes Aristotle’s prototypical definition of metaphor, that it “consists in giving a thing a name that belongs to something else”. Key words: reading visual images, Bible for the illiterate, a visual work of art as a text Kan mens ’n visuele kunswerk “lees”? ’n Bespreking van aspekte van die waarde van die algemene metaforiese verwysing na die “lees“ van afbeeldings asof hulle, soos literêre tekse, uit ’n onderliggende taalstruktuur bestaan. -

Transforming Personal Narrative Through the Art of Dolls: an Arts-Based Inquiry Into the Power of Heuristic Expansion Kelly Ann Martinez

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Action Research Projects Student Research 8-2016 Transforming Personal Narrative Through the Art of Dolls: An Arts-Based Inquiry Into the Power of Heuristic Expansion Kelly Ann Martinez Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/arp Recommended Citation Martinez, Kelly Ann, "Transforming Personal Narrative Through the Art of Dolls: An Arts-Based Inquiry Into the Power of Heuristic Expansion" (2016). Action Research Projects. Paper 2. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Action Research Projects by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2016 KELLY ANN MARTINEZ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School TRANSFORMING PERSONAL NARRATIVE THROUGH THE ART OF DOLLS: AN ARTS-BASED INQUIRY INTO THE POWER OF HEURISTIC EXPANSION Written Explanation of the Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Kelly Ann Martinez College of Performing and Visual Art School of Art and Design August 2016 This Thesis by: Kelly Ann Martinez Entitled: Transforming Personal Narrative through the Art of Dolls: An Arts-Based Inquiry into the Power of Heuristic Expansion has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Art and Design, Program of Art and Design Accepted by the Committee: _______________________________________________ Connie K. -

An Assyrian-Egyptian Battle Scene on Glazed Tiles from Nimrud Manuela Lehmann, Nigel Tallis, with Duygu Camurcuoglu and Lucía Pereira-Pardo

picture at 50mm from top frame Esarhaddon in Egypt: An Assyrian-Egyptian battle scene on glazed tiles from Nimrud Manuela Lehmann, Nigel Tallis, with Duygu Camurcuoglu and Lucía Pereira-Pardo British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 25 (2019): 1–100 ISSN 2049-5021 Esarhaddon in Egypt: An Assyrian-Egyptian battle scene on glazed tiles from Nimrud Manuela Lehmann, Nigel Tallis, with Duygu Camurcuoglou and Lucía Pereira-Pardo The tile fragments A group of glazed tile fragments1 showing scenes of an Assyrian campaign in Egypt was found during excavations in Nimrud (fig. 1a) undertaken by Sir Austen Henry Layard in early December 1849. A short description of the tiles was published by Layard in 1853, in Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the desert (1853a), chapter VII, p. 164–167, and again with a few differences in 1867, p. 52–55 and thereafter, mentioning ten tile fragments and giving a short description of each object. In addition, 11 sketched drawings were published in colour in the large folio volume A second series of the Monuments of Nineveh (1853b), pl. 53–54. These drawings were based on the sketches made in pencil and watercolour drawn by the artist Frederic Charles Cooper who accompanied Layard on this expedition, and which are now part of the Original Drawings Series (Or. Dr. II, pl. XXXV, XXXVI) at the British Museum.2 In this publication the drawings were unfortunately not reproduced to scale, which makes a comparison between them and the surviving fragments difficult. This is especially true for N2067 and N2069d, which are actually substantially larger than shown. -

Narrative Art: What Is Your Story?

Narrative Art: What is Your Story? Shared narratives can be found in art from many cultures and throughout time. Use this resource to encourage students to explore diverse narratives, discover their own personal narrative, and express that narrative through their own work of art. Grade Level: Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12 Collection: American Art, Ancient Art, Modern and Contemporary Art Subject Area: Creative Thinking, Critical Thinking, English, Fine Arts, History and Social Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Hands-On Activity, Lesson Concept OBJECTIVE The goal of this resource is to provide strategies to facilitate students’ exploration of narrative art. Using works from VMFA’s collection, students will learn how to discover the stories communicated in works of art and experience the shared human experience often expressed in these works. This process will lead students to write a personal narrative and then create their own narrative artworks. We encourage you to adapt these strategies and select works that make sense for your curriculum and classroom. While this lesson incorporates a few specific works from VMFA’s collection, the strategies modeled can be used for any narrative work of art. INTRODUCE: WHAT IS NARRATIVE ART? Begin this lesson by introducing students to the concept of narrative art and its long history. Narrative Art tells a story. It uses the power of the visual image to ignite imaginations, evoke emotions and capture universal cultural truths and aspirations. What distinguishes Narrative Art from other genres is its ability to narrate a story across diverse cultures, preserving it for future generations. – The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art Tomb Relief, 2475–2195 BC, limestone, polychrome. -

Art History (ARHI) 1

Art History (ARHI) 1 ARHI 2221. Japanese Visual Culture: Prehistory to Present. (4 Credits) ART HISTORY (ARHI) An examination of Japanese visual culture from prehistory to contemporary society. Issues and material explored: the development and ARHI 1100. Art History Introduction: World Art. (3 Credits) spread of Buddhism, temple art and architecture, narrative art and prints, This course is an introduction to the study of art history, approached from the interaction of art and popular culture, manga, anime, and contacts a global perspective. It reaches back to Cycladic art (c. 3300 to 1100 BCE) with western society. Four-credit courses that meet for 150 minutes per and ends with the present. Because most human societies have created week require three additional hours of class preparation per week on the art, this course looks at works created in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and part of the student in lieu of an additional hour of formal instruction. Africa. And since art objects can and do move across cultural boundaries, Attributes: AHGL, COLI, GLBL, INST, ISAS. it also looks at the cross-cultural transmission of artworks. Students ARHI 2223. Art and Violence in Modern Asia. (4 Credits) will learn about how peoples across space and time created works of art This course considers intersections between art and violence in modern and architecture in response to social crisis, as an aid to or container of Asia. It will focus on propaganda art from Japan, China, South Korea, ritual, and to express norms and ideals of gender. Students will come to and North Korea, and examine how violence is advocated through visual understand how and why abstraction and naturalism emerged at different language in relation to differing political ideologies, such as imperialism, times and places. -

Fractal Analysis Applied to Ancient Egyptian Monumental Art

FRACTAL ANALYSIS APPLIED TO ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MONUMENTAL ART by Jessica Robkin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2012 Copyright by Jessica Robkin 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following research paper would not be possible without the patience and understanding of my thesis committee. I am thankful for their invaluable insights, education, and support during my studies. I am particularly grateful to Dr. Clifford T. Brown for helping me to find a path of research that allowed me to do credible and important work. Thank you for introducing me to fractals, for showing me a way to bridge the gap between science and subjectivity, and for helping me every step of the way. Lastly, great thanks go out to my loved ones, whose faith has never wavered. iv ABSTRACT Author: Jessica Robkin Title: Fractal Analysis Applied to Ancient Egyptian Monumental Art Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Clifford T. Brown Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2012 The study of ancient Egyptian monumental art is based on subjective and qualitative analyses by art historians and Egyptologists who use the change in stylistic trends as Dynastic chronological markers. The art of the ancient Egyptians is recognized the world over due to its specific and consistent style that lasted the whole of Dynastic Egypt. This artwork exhibits fractal qualities that support the applicability of applying fractal analysis as a quantitative and statistical tool to be used in this field.