Policy Report on the Hungarian Minority in Szekely Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hungary's Policy Towards Its Kin Minorities

Hungary’s policy towards its kin minorities: The effects of Hungary’s recent legislative measures on the human rights situation of persons belonging to its kin minorities Óscar Alberto Lema Bouza Supervisor: Prof. Zsolt Körtvélyesi Second Semester University: Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, Budapest, Hungary Academic Year 2012/2013 Óscar A. Lema Bouza Abstract Abstract: This thesis focuses on the recent legislative measures introduced by Hungary aimed at kin minorities in the neighbouring countries. Considering as relevant the ones with the largest Hungarian minorities (i.e. Croatia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine), the thesis starts by presenting the background to the controversy, looking at the history, demographics and politics of the relevant states. After introducing the human rights standards contained in international and national legal instruments for the protection of minorities, the thesis looks at the reasons behind the enactment of the laws. To do so the politically dominant concept of Hungarian nation is examined. Finally, the author looks at the legal and political restrictions these measures face from the perspective of international law and the reactions of the affected countries, respectively. The research shows the strong dependency between the measures and the political conception of the nation, and points out the lack of amelioration of the human rights situation of ethnic Hungarians in the said countries. The reason given for this is the little effects produced on them by the measures adopted by Hungary and the potentially prejudicial nature of the reaction by the home states. The author advocates for a deeper cooperation between Hungary and the home states. Keywords: citizenship, ethnic preference, Fundamental Law, home state, human rights, Hungary, kin state, minorities, nation, Nationality Law, preferential treatment,Status Law. -

The Emergence of New Regions in Transition Romania

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289797820 The emergence of new regions in transition Romania Article · January 2009 CITATIONS READS 2 51 provided by Repository of the Academy's Library View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE 1 author: brought to you by József Benedek 1. Babeş-Bolyai University; 2. Miskolc University 67 PUBLICATIONS 254 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Socio-economic and Political Responses to Regional Polarisation in Central und Eastern Europe – RegPol² View project The Safety of Transnational Imported Second-Hand Cars in Romania View project All content following this page was uploaded by József Benedek on 14 May 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Emergence of New Regions in the Transition Romania JÓZSEF BENEDEK Faculty of Geography, „Babeş-Bolyai” University Cluj-Napoca, Clinicilor 5-7, 400 006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Email: [email protected] 1. Introduction The emergence of regions, the regionalisation of space and society, the reworking of territorial and social structures are undoubtfully strongly connected to the development of society. Social theories explaining social transformation become in this context vital, but it is quite difficult to theorise the new spatiality in transition countries like Romania and therefore we can note the first major problem which affects the analysis of socio-spatial phenomenas. Some authors were seeking to theorise transition in Romania, J. Häkli (1994), D. Sandu (1996, 1999), V. Pasti et. al. (1997), W. -

Identity Discourses on National Belonging: the Hungarian Minority in Romania 1

"This version of the manuscript is the authors’ copy, prior to the publisher's processing. An updated and edited version was published in the Romanian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 14, No. 1, Summer 2014 pp 61-86 Identity discourses on national belonging: the Hungarian minority in Romania 1 2 Valér Veres ABSTRACT This paper deals with national representations of the Hungarian minority from Transylvania and its group boundaries within the context of the Hungarian and Romanian nation. The main empirical source is represented by qualitative data, based on a focus group analysis from 2009. It analyses the ways in which Hungarians from Transylvania reconstruct national group boundaries based on ideological discourses of nationalism, including specific differences that may be observed in discursive delimitations within the minority group. The study focuses on the following three research questions. The first one refers to the national boundaries indicated, to the interpretations given to belonging to a nation. The second one refers to the way people name their homeland and the interpretations they relate to it. The third one refers to the way Hungarians from Transylvania relate to Hungary. Based on focus group answers, two marked national discourses may be distinguished about the representations of Hungarians from Transylvania regarding nation and national belonging. The two main discourses are the essentialist-radical and the quasi-primordial – moderate discourse. Conceptually, the discourses follow Geertz’s typology (1973). As for the Hungarian minority form Romania, we may talk about a quasi- primordialist discourse which is also based on cultural nation, but it has a civic nation extension towards Romanians. -

Minority Politics of Hungary and Romania Between 1940 and 1944

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, EUROPEAN AND REGIONAL STUDIES, 16 (2019) 59–74 DOI: 10 .2478/auseur-2019-0012 Minority Politics of Hungary and Romania between 1940 and 1944. The System of Reciprocity and Its Consequences1 János Kristóf MURÁDIN PhD, Assistant Professor Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) Faculty of Sciences and Arts e-mail: muradinjanos@sapientia .ro Abstract . The main objective of the paper is to highlight the changes in the situation of the Hungarian minority in Romania and the Romanian minority in Hungary living in the divided Transylvania from the Second Vienna Arbitration from 30 August 1940 to the end of WWII . The author analyses the Hungarian and Romanian governments’ attitude regarding the new borders and their intentions with the minorities remaining on their territories . The paper offers a synthesis of the system of reciprocity, which determined the relations between the two states on the minority issue until 1944. Finally, the negative influence of the politics of reciprocity is shown on the interethnic relations in Transylvania . Keywords: Transylvania, Second Vienna Arbitration, border, minorities, politics of reciprocity, refugees Introduction According to the Second Vienna Arbitration of 30 August 1940, the northern part of Transylvania, the Szeklerland, and the Máramaros (in Romanian: Maramureş, in German: Maramuresch) region, which had been awarded to Romania twenty years earlier, were returned to Hungary (L . Balogh 2002: 5) . According to the 1941 census, the population of a total of 43,104 km2 of land under Hungarian jurisdiction (Thrirring 1940: 663) was 2,557,260, of whom 53 .6% were Hungarian and 39 .9% were Romanian speakers . -

Ethnic Hungarians Migrating from Transylvania to Hungary

45 Yearbook of Population Research in Finland 40 (2004), pp. 45-72 A Special Case of International Migration: Ethnic Hungarians Migrating From Transylvania to Hungary IRÉN GÖDRI, Research Fellow Demographic Research Institute, Hungarian Central Statistical Offi ce, Budapest, Hungary Abstract The study examines a special case of international migration, when the ethnicity, mother tongue, historical and cultural traditions of the immigrants are identical with those of the receiving population. This is also a fundamental feature of immigration to Hungary in the last decade and a half and could be observed primarily in the migratory wave from neighboring countries (most of all from Transylvania in Romania). After presenting the historical background we will review the development of the present-day migratory processes as well as their social and economical conditions, relying on statistics based on various sources. The socio-demographic composition of the immigrants and their selection from the population of origin indicate that migration is more frequent among younger, better-educated people living in an ethnically heterogeneous urban environment. At the same time, the rising proportion of older people and pensioners among the immigrants suggests the commencement of the so-called “secondary migration.” This is confi rmed by a questionnaire-based survey conducted among immigrants, which showed that family reunifi cation is a migratory motivation for a signifi cant group of people, primarily for the older generation. Among younger people economic considerations are decisive in the migrants’ decision-making. Our analysis underscores the roles of ethnicity and network of connections in the processes under examination. Keywords: international migration, Hungary, ethnic minority, Transylvania, ethnic- ity, network Introduction Due primarily to the social and political transformations in Eastern and Central Europe, we have been witnessing signifi cant changes after the end of the 1980s in migratory patterns in Hungary. -

Atrocities Against Hungarians in Transylvania-Romania in The

THE WHITE BOOK ATROCITIES AGAINST HUNGARIANS IN THE AUTUMN OF 1944 (IN TRANSYLVANIA, ROMANIA) RMDSZ (DAHR) KOLOZSVÁR, 1995 by Mária Gál Attila Gajdos Balogh Ferenc Imreh Published originally in Hungarian by the Political Section of the Acting Presidium of the DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE OF HUNGARIANS IN ROMANIA (DAHR) Publisher: Barna Bodó Editor: Mária Gál Lector: Gábor Vincze Corrector: Ilona N. Vajas Technical editor: István Balogh Printed by: Écriture Press Printing House Manager in charge: Gyula Kirkósa Technical manager: György Zoltán Vér Original title: Fehér könyv az 1944. öszi magyarellenes atrocitásokról. Foreword 75 years have passed since Trianon, the humiliating and unfair event that has been a trauma for us, Hungarians ever since. Even though we had 22 years at our disposal for analyzing and defining political and social consequences, the next disastrous border adjustment once again driven us to the losers’ side. Since then, the excruciating questions have just multiplied. When was the anti-Hungarian nature of the second universal peace agreement decided upon? What were the places and manners of this fatal agreement, which, although unacceptable to us, seemed to be irrevocable? Some questions can probably never be answered. Devious interests have managed to protect certain archives with non- penetrable walls, or even succeeded in annihilating them. Other vital events have never really been recorded. Lobbying procedures are not the invention of our age... State authorities could easily ban prying into some delicate affairs if special cases – like ours – occurred. There seemed to be no possibility for answering the question of the bloodshed in the autumn 1944 in North Transylvania. -

Download This Report

STRUGGLING FOR ETHNIETHNICC IDENTITYC IDENTITY Ethnic Hungarians in PostPostPost-Post---CeausescuCeausescu Romania Helsinki Watch Human Rights Watch New York !!! Washington !!! Los Angeles !!! London Copyright 8 September 1993 by Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-115-0 LCCN: 93-80429 Cover photo: Ethnic Hungarians, carrying books and candles, peacefully demonstrating in the central Transylvanian city of Tîrgu Mure’ (Marosv|s|rhely), February 9-10, 1990. The Hungarian and Romanian legends on the signs they carry read: We're Demonstrating for Our Sweet Mother Tongue! Give back the Bolyai High School, Bolyai University! We Want Hungarian Schools! We Are Not Alone! Helsinki Watch Committee Helsinki Watch was formed in 1978 to monitor and promote domestic and international compliance with the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. The Chair is Jonathan Fanton; Vice Chair, Alice Henkin; Executive Director, Jeri Laber; Deputy Director, Lois Whitman; Counsel, Holly Cartner and Julie Mertus; Research Associates, Erika Dailey, Rachel Denber, Ivana Nizich and Christopher Panico; Associates, Christina Derry, Ivan Lupis, Alexander Petrov and Isabelle Tin- Aung. Helsinki Watch is affiliated with the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which is based in Vienna, Austria. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some sixty countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process of law and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. -

Anti-Hungarian Manifestations in Romania

Editor: Attila Nagy ANTI-HUNGARIAN MANIFESTATIONS IN ROMANIA 2017–2018 2017 According to Dezső Buzogány university professor, one of the translators, the lawsuit issued in connection It is outrageous and against education, that the to the restitution of the Batthyaneum may last longer Hungarian section grade 5 of fine arts in the János than expected because the judge, who should have taken Apáczai Csere High School in Kolozsvár (Cluj- the decision in the case - is retiring in February and Napoca) has been dismissed. With this step taken, this case, that attracts significant interest, is to be taken the future of the only Hungarian fine arts section in over by someone else. Meanwhile, the analysis of the mid-Transylvania became compromised – stated the translation of the testament of bishop Ignác Batthyány Miklós Barabás Guild (Barabás Miklós Céh/Breasla by experts hired both by the plaintiff and by the Barabás Miklós) in its announcement. respondent, is still going on. It is only after this process The news of the dismissal of the class has had neg- that the court of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia) can be ative echo abroad since the art training practiced at expected to pronounce a decision in the lawsuit in which Apáczai High School has gained recognition not only the Roman Catholic Church demanded the nullification at home but on an international scale as well. The an- of the decision of the restitution committee rejecting nouncement insists on the importance of insertion by restitution. The late bishop left his collection of unique the School Inspectorate of Kolozs (Cluj) County of a new value to the Catholic Church and Transylvania Province. -

Agata Tatarenko Another Tension in Romanian-Hungarian Relations

Editorial Team: Beata Surmacz (Director of ICE), Tomasz Stępniewski (Deputy No. 195 (98/2020) | 16.06.2020 Director of ICE), Agnieszka Zajdel (Editorial Assistant), Aleksandra Kuczyńska-Zonik, Jakub Olchowski, Konrad Pawłowski, Agata Tatarenko ISSN 2657-6996 © IEŚ Agata Tatarenko Another tension in Romanian-Hungarian relations At the end of April 2020, the Romanian Parliament dealt with a bill aimed at establishing an autonomous region covering areas inhabited by the Hungarian-speaking ethnic group Székelys. The bill was rejected by the senate, however, the initiative caused a number of controversies on the political scene in Romania, including, above all, the statement of President Klaus Iohannis. The President’s statement was criticized by the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Romanian National Council for Combating Discrimination. The whole matter is more contentious because of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Trianon Treaty, which was celebrated this year. June 4th, 1920, was marked differently in the history of these two countries: as the emergence of Greater Romania and as the end of Greater Hungary. In the region of Central Europe, history plays a special role, which was clearly demonstrated by the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Trianon. This uneasiness can be observed in the area of bilateral relations and it is particularly clear in the case of Hungary and Romania. (The anxieties in the region can be observed in the context of bilateral relations and they are particularly clear in the case of Hungary and Romania). The source of tension in the Hungarian-Romanian relations lies in Transylvania (Rumanian Transilvania or Ardeal, Hungarian Erdély). -

Romania Assessment

Romania, Country Information Page 1 of 52 ROMANIA October 2002 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURE VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATION ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE REFRENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=189&title=Romania%2C%20Country%20Informat...i 11/25/2002 Romania, Country Information Page 2 of 52 2.1 Romania (formerly the Socialist Republic of Romania) lies in south-eastern Europe; much of the country forms the Balkan peninsula. -

Granville Outcover.Indd

The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Johanna Granville Number 1905 “If Hope Is Sin, Then We Are All Guilty”: Romanian Students’ Reactions to the Hungarian Revolution and Soviet Intervention, 1956–1958 The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1905 Johanna Granville “If Hope Is Sin, Then We Are All Guilty”: Romanian Students’ Reactions to the Hungarian Revolution and Soviet Intervention, 1956–1958 Dr. Johanna Granville is a visiting professor of history at Novosibirsk State University in Russia, where she is also conducting multi-archival research for a second monograph on dissent throughout the communist bloc in the 1950s. She is the author of The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956 (2004) and was recently a Campbell Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, USA. No. 1905, April 2008 © 2008 by The Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X Image from cover: Map of Romania, from CIA World Factbook 2002, public domain. The Carl Beck Papers Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Ronald H. Linden Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Vera Dorosh Sebulsky Submissions to The Carl Beck Papers are welcome. Manuscripts must be in English, double-spaced throughout, and between 40 and 90 pages in length. Acceptance is based on anonymous review. Mail submissions to: Editor, The Carl Beck Papers, Center for Russian and East European Studies, 4400 Wesley W. Posvar Hall, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. Abstract The events of 1956 (the Twentieth CPSU Congress, Khrushchev’s Secret Speech, and the Hungarian revolution) had a strong impact on the evolution of the Romanian communist regime, paving the way for the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Roma- nia in 1958, the stricter policy toward the Transylvanian Hungarians, and Romania’s greater independence from the USSR in the 1960s. -

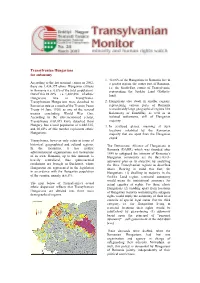

Transylvanian Hungarians for Autonomy 1

Transylvanian Hungarians for autonomy 1. 42,66% of the Hungarians in Romania live in According to the last national census in 2002, a greater region, the centre part of Romania, there are 1,434,377 ethnic Hungarian citizens i.e. the South-East corner of Transylvania, in Romania (i.e. 6.6% of the total population). representing the Szekler Land (Székely- Out of this 98.29% – i.e. 1,409,894 – of ethnic land). Hungarians live in Transylvania. Transylvanian Hungarians were detached to 2. Hungarians also dwell in smaller regions, Romanian rule as a result of the Trianon Peace representing various parts of Romania Treaty (4 June 1920) as one of the several (considerably large geographical regions like treaties concluding World War One. Kalotaszeg or Érmellék), as well as in According to the aforementioned census, isolated settlements, still of Hungarian Transylvania (103,093 km²), detached from majority. Hungary, has a total population of 6,888,515, 3. In scattered places, meaning at such and 20,46% of this number represents ethnic locations inhabited by the Romanian Hungarians. majority that are apart from the Hungarian chunk. Transylvania, however only exists in terms of historical, geographical and cultural regions. The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in In the meantime, it has neither Romania (DAHR) which was founded after administrational organizations, nor institutions 1989 to safeguard the interests of Romania’s of its own. Romania, up to this moment, is Hungarian community set the three-level- heavily centralized, thus quintessential autonomy plan as its objective by analyzing resolutions are brought in Bucharest, where the three Transylvanian regions as described Hungarians are represented in the legislation above.